I Want to Feel the Love

I glimpse the infinitely unknowable face of G-d and I tremble

He loves me. He loves me not. He loves me. He loves me not.

A childhood memory: I’m sitting cross-legged on the grass, plucking petals from a daisy in this game where love is a random chance, waiting for the final petal to fall: odd or even, for or against, love or abandonment.

He loves me. The sun shines this morning.

He loves me not. A child is lowered into the belly of the earth.

He loves me. My children are safe.

He loves me not. Human faces, distorted by pain, like a ghastly reflection in a funhouse mirror, bringing up strange and difficult childhood memories.

He loves me. I have a job, a home, a place in this world. Meaning.

He loves me not. The million faces of human suffering, each telling its own story. Evil inflicted by one generation onto another. The whistling emptiness of the desolate deep.

I pluck petals from daisies, wondering, achingly trying to make sense of our lives and world events, the paucity of our understanding. An unsettled childhood left lingering suspicion, and I vacillate between these two childish poles, for in my pain it becomes impossible to hold ambiguity, reach for integration, strive for a more sophisticated conception of the Divine.

I glimpse the infinitely unknowable face of G-d and I tremble.

And I am left standing in a field, holding a daisy shorn of petals. Whatever the outcome of this flower — love me, love me not — there will always be another daisy and another, a million daisies or maybe six million, always with a different answer. He loves me, He loves me not.

Childlike, I long to return to the image of G-d-as-Zeide. Wide smile, a stroke on the cheek (at most an affectionate pat), handing out jellybeans. I want the G-d of erech apayim, of beni bechori Yisrael. And when we are faced — or so it seems to us — by the G-d of charon af, of Hastir Astir es pani, of lamah azavtani, I slink away, afraid of some encroaching annihilation.

All I wanted was to savor that jellybean, feel it melt in my mouth, filling me with the knowledge that all is well with the world, that all is well with me. Instead, I walk around with a heart that is shattered, knowing that the alternative — to chalk up this catastrophe to people, to irresponsibility, to the general chaos and entropy of the universe — would break my spirit, and I know that G-d is not just invisible; He is unfathomable.

A child says Kaddish for his father, and a father for his child. Each day I am confronted with the seeming banality, not of evil, but of suffering — for we soon learn that not all suffering ennobles, it may even be self-inflicted, and not every challenge necessarily brings us to growth. What, then, can we can do to fight despair and bitterness and cynicism, to quiet the question hurled between Beis Shammai and Beis Hillel: Would it have been better had man never been created?

***

Writer’s craft: A character is known through his actions. Put your character into motion, let them bump up against antagonists and life circumstances, and we learn his strengths and flaws, his wishes and secrets. Speech, responses, behaviors — we consider them all, crafting a close-up view into who and what the protagonist wants, thinks, is. And yet, there is another way we can know character. It is through the people who surround him. Make his children heros, make his sons noble and selfless and his daughters generous and considered, and we know exactly who the character is. He need not say a single word.

We do not know G-d and we can never know him. Love me, love me not — all fades into something awesome and mysterious that no mortal man can ever fathom. But if we do not know G-d, we can know something of those who dedicate their lives to His service.

Many stories are emerging about Hashem’s children. Here is one of them.

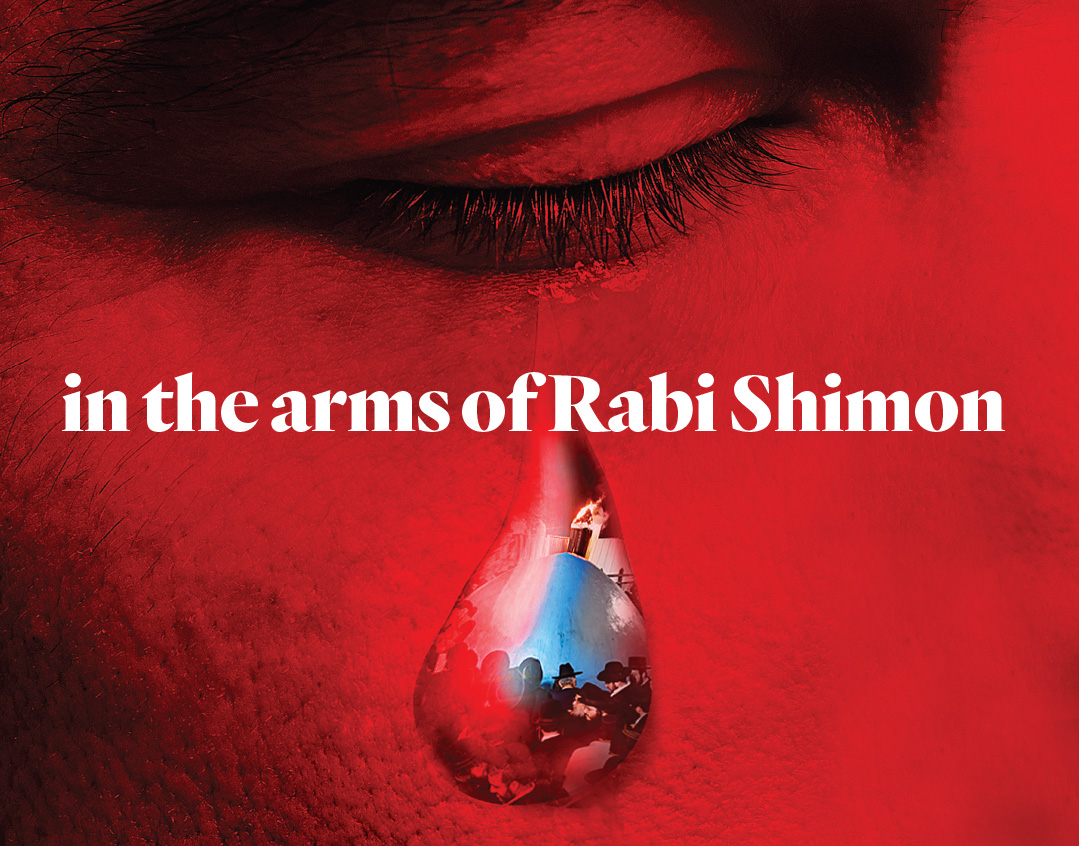

On Thursday night, as victims were being trampled to death, they tossed their final words into the abyss. What were those words? Mochel lecha. Ani mochel otcha, I forgive you.

Absolving those around them for responsibility. Giving survivors the gift of a life unburdened by guilt. Leaving the world with a thought to those who will go on living. Thinking not of their agony, but of their fellow Jews.

Mochel lecha. The words thrum within me, filling my heart, squeezing, pumping something akin to hope through me. A hope that contains bewildered awe at how flesh and blood and beating heart can transcend itself. A hope that I can find it in myself to reach out, love, accept, and continue my lifelong quest to know my Creator.

For we may not know G-d, but we know His creations.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 859)

Oops! We could not locate your form.