“I Think Pull Is…”

Protektzia is baked into our society. Should it be?

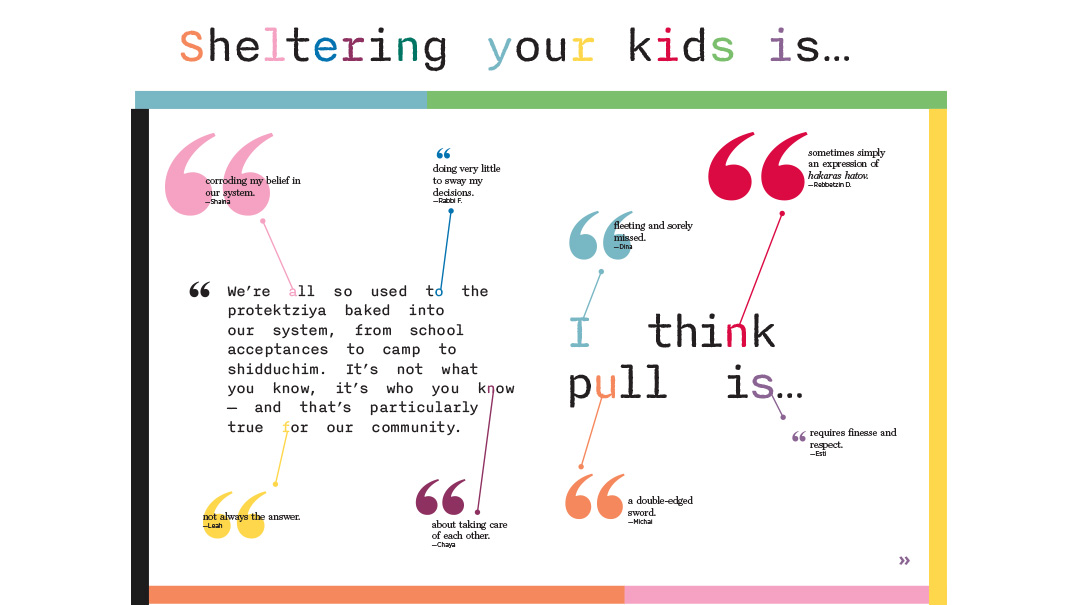

We’re all so used to the protektziya baked into our system, from school acceptances to camp to shidduchim. It’s not what you know, it’s who you know — and that’s particularly true for our community.

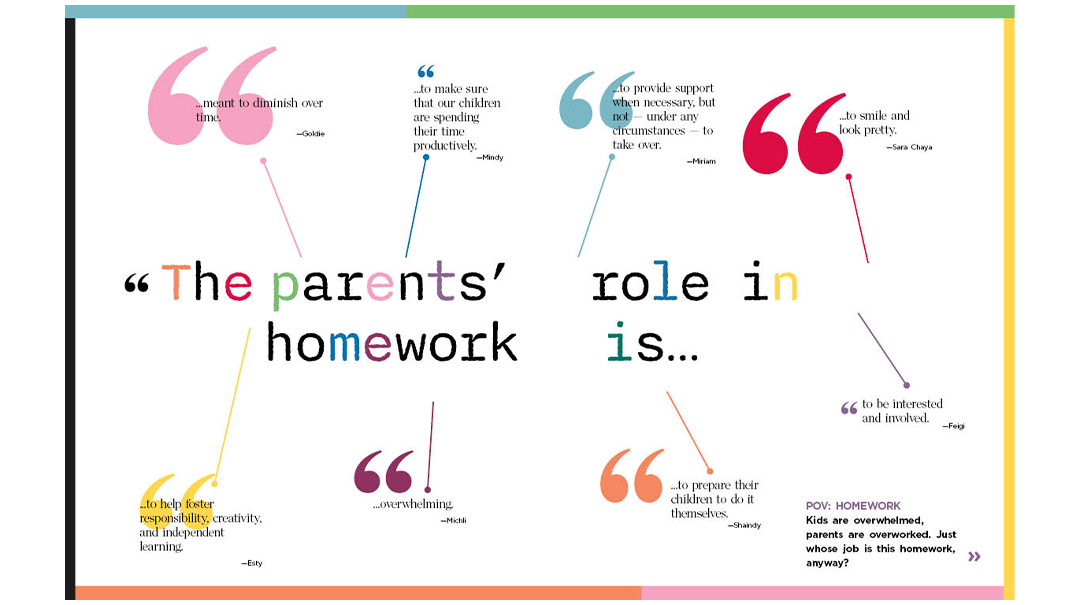

I think pull is…

corroding my belief in our system.

For yeshivah and seminary, the application process means that students are interviewed and can showcase their talents and hard work. But camp? Camp is a numbers game. There aren’t enough spots for all the applicants, so if you don’t know someone with pull, the door doesn’t even open for you. You’re automatically waitlisted. So I embarrass myself by calling every person I know who might know someone. I’m told again and again, “This is just how the system works. If you don’t beg or plead, they won’t accept you.”

This system engenders disgust (how could a system like this be aligned with Torah?), insecurity (I guess I’m not choshuv enough to matter), and a competitive every-man-for-himself spirit (you’ve got to do what you’ve got to do). Protektziya is so deeply entrenched in our system that people no longer feel outrage about it; they simply shrug their shoulders and start making their phone calls. Is this really how it’s supposed to be?

—Shaina

doing very little to sway my decisions.

I am a community rav who meets with many people about a wide range of issues. Sometimes, people who want an appointment for counseling or advice will attempt to influence the situation, sometimes to get an appointment sooner or to push an agenda. Many of them believe that if they casually drop a name, I’ll be more inclined to give them what they want. I guess they feel that if they know someone I respect or have a relationship with, then I’ll be more inclined to do what they want. (Someone actually once mentioned that his daughter and my four-year-old granddaughter were very close!)

This technique is completely off the mark. I’m not going to juggle my schedule or meet someone at midnight on Motzaei Shabbos because they know a name. I think, like most rabbanim, I will accommodate requests when I feel an achrayus to care for that person — whether they’re a member of my kehillah, they’re in need of something I can uniquely offer, or they’re just a Jew who has no one else besides HaKadosh Baruch Hu to share their burden. Nothing creates a positive response more than being told, “I’m counting on you. I have nowhere else to turn.”

On occasion, I need to use my own name, whether to get someone an interview or a medical appointment or admission to a yeshivah. I try to focus on how I feel when people pull on my strings, and I prefer the honest and direct approach. I express to the employer or physician or menahel that I recognize their position, but Hashem has placed His child squarely in our laps and we have to find a way to bend so we can see Hashem’s salvation unfold. I guess that’s also name-dropping.

—Rabbi F.

not always the answer.

I am blessed with a daughter who’s at the top of her class, with the middos to match. When applying to high schools, though, I was told that this wouldn’t make a difference with her top choice. You need to be realistic. No one gets into that school without pull. I did have connections that I could have used, but in the end, I didn’t ask them to put in a word for her. After all, I thought, if the school wouldn’t take a top girl on her own merits, then what did that say about the caliber of the girls they were accepting?

Baruch Hashem, she did get in, and I was able to register her without any lingering doubts. But I also know that every girl isn’t that fortunate. The girls in the 100 range might easily get into schools and seminaries. But when she’s a 95-range student surrounded by dozens of other 95 students, then what else distinguishes her from her peers? Sometimes that protektziya is nothing so nefarious — it’s just about making a personal connection in a sea of faceless applications.

—Leah

about taking care of each other.

I live in a smaller community, and for us, it’s not really about pull. It’s about the communal responsibility that we all feel to take care of our children. How can we accept a child into our schools in nursery and then leave them stranded when they hit eighth grade? How can we let one child suffer without the opportunities that their peers are getting? So rabbanim will advocate and askanim will make calls because we have no choice but to take care of every single child.

—Chaya

fleeting and sorely missed.

For many years, I worked in a field that gave me access to community and political leaders. There was no problem I had that couldn’t be solved with a well-placed phone call. Whether it was using my connections to get out of a speeding ticket or getting friends high-paying jobs with an offhand comment, the world was my oyster. And then, I moved.

In my new neighborhood, I was anonymous, and I quickly learned how not fun it could be. Yes, I could do my Shabbos shopping in a tichel because there was no danger of running into a colleague, but when it came time to get my son into cheder, I suddenly realized that I had no one to call.

I’d like to say that the lesson learned was that protektziya isn’t fair to those who don’t have it, but I’m not so evolved. The truth is that if I had it, I’d use it. Let’s not pretend otherwise.

—Dina

sometimes simply an expression of hakaras hatov.

As a principal, I have to weigh all elements of a situation. If I have two girls who are both deserving of the same one slot, then my decision might be a matter of hakaras hatov to someone I know who’s advocated for them. Obviously, if they’re not deserving, then there’s no discussion.

Our menahel is very adamant that this isn’t a school where donors’ children get preferential treatment. However, when I hear from the fundraising division that a certain parent is advocating for their daughter to get into a specific class and it’s just a question of space and not qualifications, I do consider it — for the fundraising division, to make their job a little easier.

—Rebbetzin D.

a double-edged sword.

I think pull is both a service and a disservice to the kids whose families are using it. Recently, a girl needed help getting into a seminary where the hanhalah owed me a favor. I made the call, but the principal was overwhelmed. “I’m getting calls from gedolim. I’m getting calls from people who’ve done so much for me. And they all want these girls in the school. But I just don’t have the beds. How can I say no to any of you?” In the end, those girls might be accepted, but at what cost? For overcrowded rooms and classes?

—Michal

requires finesse and respect.

Most rabbanim, principals, and mechanchos — all of them recipients of similar calls — understand what you mean when you say, “The person you are calling about is not a fit for our school.”

As the one in charge of admissions, I’ve found that the least effective way to get kids into our institution is trying to bribe or threaten us. Most people think that a large offer of cash will get a child accepted or pushed to the top of a waiting list, but I know many, many people who will run in the opposite direction as soon as they hear someone move in that direction. The quid pro quo is never worth it, and the admissions department knows it.

Sometimes people who “pay their way” find it very difficult to accept a firm no, and that’s how you can tell a truly respectable person from a wealthy person who thinks he should be respected. A respected person will use their position to gently push, but will then accept the rejection; someone who pays their way often resorts to threats and rudeness when they discover that their money won’t push their child to the top of the list.

—Esti

a brachah.

Honestly, I feel like people need to show up first with their own merits. But if someone has enough protektziya to be singled out of a crowd of similarly deserving peers, it’s reasonable to use that pull. The world will never be free of nepotism. It’s a brachah to know people who know people. At the same time, people must recognize that having connections doesn’t make them more worthy. So they shouldn’t get fussy when their protektziya fails them — rather, keep in mind that they weren’t meant to be in this place.

—Ilana

a fear to be overcome.

Administrators live with a lot of fear that drives their decisions. Much of it is legitimate. They won’t be able to fund their schools without the support of specific parents, and they’re afraid of upsetting them.

But that’s where these administrators need to be stronger and have wider shoulders than the rest of us. They’re leaders, and it’s upsetting when they’re so afraid to say no to certain parents that they give that donor’s child a spot instead of giving a chance to another kid who really is worthy but doesn’t have the connections or the money to match. It takes away some of our trust in the system. How can we explain to our kids that they can put in the middos and effort and time to rise to the top, but it doesn’t really matter in the end — all that matters are your connections?

We need to insist on a higher level of idealism from our leaders. To me, that fear comes from a lack of emunah that Hashem will take care of them. And what are we telling our children then?

—Chana

a matter of practicality.

Everyone understands the basic concept of hakaras hatov. When you do me a favor, I owe you a favor. I owe favors to people who have been generous with my mosad, and it would be ungrateful if I self-righteously refused their requests. If someone is a donor, a friend, or a neighbor, you’d accept them first, too. Anyone who says they wouldn’t prioritize a friend or a relative is either lying or unhealthy.

But there’s another aspect: limited time and resources.

When two children apply to my school, even though we love them both and Hashem loves them both, I still need to cover my payroll. So, yes, I’ll prioritize the one who gives me an extra $25,000. People don’t like it — they feel like they’re cattle being traded — but I’m not a tzedakah organization; I can’t afford to act only out of compassion.

I have experience on both sides of the desk. I once tried to push a troubled bochur into a mesivta. The menahel was very blunt. He said, “I have a budget. I don’t have as much time as I’d like to deal with every kid’s mischief. If you beg me to take this boy, then every time he acts up, I’ll have to sit with him in my office and lecture him. For an extra $20,000, I’ll be able to afford the time to deal with him.” Yes, there are nicer ways to say it, but the point remains: Every student uses time and resources from a finite pool, so we can’t just be baalei chesed and take everyone who wants to come.

Once the kids are in the school, a healthy chinuch environment will treat all kids the same way. My daughter gets sent out of class just like anyone else’s. Being the dean’s daughter doesn’t get her any special treatment.

—Rabbi Y.

a question of finances.

People look at protektziya like it’s something sleazy, but often it’s about doing what’s best for the mosad. If someone is a major donor, how can I refuse his child/grandchild/person-that-he-owes-a-favor-to? Without his donations, no one would have any school at all. Until schools become community-funded enterprises that don’t rely on the generosity of specific individuals, we need to cultivate the goodwill of the donors if we want to have schools at all.

And that’s besides the fact that the money itself is what enables me to take these kids. There was one incident where I’m sure word got out that we accepted a child on the basis of a $50,000 donation. I’m sure people kvetched that we were extorting the rich and leaving the poor out in the cold. In fact, the money went toward construction and hiring extra staff to accommodate an extra child in a packed classroom. If I told him we had no space, and he was able to pay to make the space, should I have said no just because other people can’t afford to do the same?

—Rav G.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 924)

Oops! We could not locate your form.