How the West Was Won

Rabbi Yochanan Stepen transformed the Torah landscape of Los Angeles

Rabbi Yochanan Stepen’s many students, admirers, and friends remember him as a magical presence, a larger-than-life hero come to lead the children of the Valley — and by extension their parents — into the enchanting realm of Torah. His outsized personality and magnetism drew kids to him like bees to honey.

His charisma had its source in his immense love and enthusiasm for Torah and Jewish children. As a mechanech and the educational director of Emek Hebrew Academy for 31 years, his bren for Torah set everyone around him on fire.

Erev Yom Kippur marks Rabbi Stepen’s fourth yahrtzeit, but his imprint on the Valley remains vibrant and thriving. When he started at Emek in 1973, the school had 70 students. Today, the student body numbers almost 1,000, with an immense campus and separate early childhood center.

How did one man accomplish so much?

Who Will Learn with My Son?

For Rabbi Stepen a"h, a Jew was a Jew — no matter what he looked like or how little he knew. He understood that if a Jew isn’t religious, it’s because no one ever showed him the beauty of Torah.

Rabbi Stepen’s parents, the children of Russian immigrants, eked out a living in the dry-cleaning business in a rough neighborhood in downtown Chicago. The children went to public school, but Yochanan, the second child of three and the oldest boy, always felt drawn to Yiddishkeit.

“His parents sent him to a sleepaway camp when he was about six years old that must have been Orthodox,” says his daughter Mirie Lazar. “After that, as a kid, he would make ‘Shabbos classes’ for the other kids. He’d even find people to come speak to them.”

When he approached bar mitzvah age, his mother brought him to the Skokie Yeshiva. “Can someone here help my son learn for his bar mitzvah?” she asked.

“I’ll learn with him,” volunteered a bochur named Gershon Weinberg. The two bonded, to the point where Gershon wrote a play designed for Yochanan to take the starring role. He ultimately influenced Yochanan to make the switch from the local high school to the Skokie Yeshiva.

After high school, he continued his yeshivah studies in Eretz Yisrael in Yeshivas Chevron, undeterred by the lack of American peers and his inability to speak much Hebrew. The mashgiach, Rav Hirsch Paley, took him under his wing, and he developed close relationships with the roshei yeshivah, Rav Yechezkel Sarna and Rav Simcha Zissel Broide. He would walk Rav Zalman Sorotzkin home from shul and be meshamesh him. He also developed a close friendship with Rav Hillel Zaks. Another of his chavrusas and mentors was Rav Baruch Mordechai Ezrachi, now rosh yeshivah of Ateres Yisrael and a member of the Degel HaTorah Moetzes Gedolei Yisrael. Although a few years older, Rav Ezrachi remained a close personal friend over the years. He would visit Rabbi Stepen when he was in Los Angeles, and Rabbi Stepen would go see him when he was in Eretz Yisrael. In fact, Rav Ezrachi was one of the maspidim at Rabbi Stepen’s levayah.

His living conditions were rough, but Rabbi Stepen learned with tremendous hasmadah and was soaring in lomdus. “He was undeterred by the fact that he was the only American boy there, that he didn’t have money and sometimes even food,” his wife, Mrs. Chana Stepen, relates. Their son Rabbi Eliezer Stepen, who heads Kollel Zichron Yochanan in Jerusalem, adds, “He used to borrow money from a makolet for food. After he left, it took him seven years to pay it back.”

Rabbi Stepen was a visionary who wanted Emek to be a showcase, a school without compromise yet that even non-frum families could relate to.

Class Act

In 1963, Rabbi Stepen returned to the United States for his sister’s wedding. He thought he might enroll in college there; he had a strong interest in biology and medicine, and contemplated becoming a pediatrician or heart surgeon. But he ultimately pursued a different trajectory when an anonymous donor offered to fund the building and operation of a nursery school in Los Angeles. Upon landing in L.A., however, the donor backed out at the last minute, and instead Rabbi Stepen took a job in a warehouse to pay his rent.

One day in shul, he met his future mentor, Rabbi Menachem Gottesman, the head of the Hillel Hebrew Academy. The two became friendly, and Rabbi Gottesman invited him to a Labor Day get-together for the school in a local park. During the event, Rabbi Gottesman’s attention was suddenly drawn to a crowd gathered in a large circle. It turned out that his new friend Yochanan Stepen was telling stories to the children, who’d been drawn to him as if he were a Pied Piper.

“He was a born storyteller,” says his son-in-law and Mishpacha CEO Avi Lazar. “He fiered the Shabbos tish like a classroom, gluing restless grandchildren — and children — to their seats with mesmerizing divrei Torah and stories. Kids would earn ‘Zeidy gelt’ for good answers to questions.

“My shver was old school,” Avi continues. “He was a master mechanech, proficient administrator, and highly skilled fundraiser. The complete package — something that today requires the efforts of a number of people. But his true love was teaching Torah.”

Realizing he was in the presence of real chinuch talent, Rabbi Gottesman approached him. “I think you’ll be joining us at Hillel,” he said. He hired him as a rebbi for boys ages ten through 12 and assigned him the boys who struggled with learning.

“He could explain anything to anyone and make it fun in the process,” Mirie Lazar remembers.

Now that Rabbi Stepen would be leaving his job in the warehouse, he didn’t have a way of paying his rent. Rabbi Gottesman offered him lodging in his guest house, and he became a ben bayis in the Gottesman home. He “paid” by babysitting the Gottesman children when their parents had to attend social functions in the evenings. When his brother Freddy came to L.A., the two of them ran the Hillel day camp together.

“They were everything — the directors, the bus drivers, the counselors,” Mrs. Chana Stepen remembers.

It was Mrs. Leiba Gottesman who decided it was time to find him a shidduch. She invited two young women for Shabbos lunch, took him into the kitchen, and told him, “Pick one!”

His choice was Chana Bertman, whose brother, Reb Shimon Bertman, later became one of the beloved maggidei shiur on Rabbi Eli Teitelbaum’s Dial-a-Daf. The couple took off from work for their shanah rishonah and went to Eretz Yisrael, promising to return a year later.

A dancing Rabbi Stepen and devoted partner Mr. Sol Teichman at the hachnasas sefer Torah to Emek’s Teichman Family beis medrash

A Friend in Need

When shanah rishonah was over, the Stepens left Eretz Yisrael with great reluctance, even tears. They’d asked gedolim if they could stay, but the response was that Rabbi Stepen was needed in LA. Rabbi Stepen resumed at Hillel, where he was enlisted to help on the administrative end as well. Those talents soon led to the offer of a principal’s job at Bais Yaakov of Los Angeles.

He was there for two years when a new opportunity arose: to be the principal at Emek, a school founded by members of the Shaarey Zedek synagogue in the Valley.

“There was a group of balabatim, led by Larry Tover, who had seen him in action and wanted him on board,” Mrs. Stepen says. “Most of them were ten or 12 years older than he was, but they became very close.”

Dr. Josh Penn, a Valley native and former talmid, says there was a ragtag group of about 12 core families who banded together to launch the school. The families were mostly transplants from elsewhere and didn’t have extended family in the area. “The Emek Mafia,” he jokes. “We did everything together — for example, the families would make a Fourth of July picnic, or rent a hotel and spend Shavuos together. We kids grew up like cousins.”

There were very few shomer Shabbos families in the area, and Emek was billed as a community school. Rabbi Stepen, himself the product of a non-observant home, had a natural sympathy for students from similar backgrounds. “He saw Emek as an opportunity to grow,” Mrs. Lazar says. “It was a school where he could truly make a difference. Once there, he never turned anybody away who wanted to come.”

His title was educational director, but given the fledgling status of the school, he doubled as a fundraiser and did a magnificent job, putting his interpersonal skills to good use. The rebbeim were always paid on time.

“He said it shouldn’t be called fundraising; it should be called friend-raising,” says his brother Dr. Freddy Stepen.

“He would go to someone’s office and not leave until he got what he needed,” daughter Mrs. Sarah Manne relates. “If someone wrote a check that he considered too low, he’d rip it in half and refuse to leave until he got what he wanted. And everyone loved him anyway. He was just so determined.”

Rabbi Stepen happily put aside his own kavod for the greater good of the yeshivah. One year, he decided that instead of running a typical yeshivah dinner with boring speeches and catered food, he’d rent the Calamigos Ranch and make a family-friendly barbecue and carnival as a fundraiser. There were hot dogs and hamburgers, a petting zoo and bouncy house, and one of the fundraising attractions was a dunk tank. Someone would sit high on a bench and the participants would pay to lob baseballs at a target. If they hit it, the bench would tip the person into a tank of water.

“How much are you charging for a throw?” Rabbi Stepen asked. When they told him it cost a dollar, he told a non-religious gvir, “Make it a hundred dollars, and you can dunk me!” He got on the bench, to the great entertainment of his talmidim, and was dunked until he decided he’d raised enough money for the school.

Mrs. Manne says her father is still fundraising for Emek from Shamayim. Shortly after his petirah, a check for $10,000 mysteriously appeared at the yeshivah. Rabbi Mordechai Shifman, the current educational director, recounts, “During Covid we had to close the yeshivah doors for a time, but once in a while I’d go into my office. One day I came in to retrieve a pile of mail, and I found this large check from a lady named Donna Levy in Tampa, Florida. I didn’t recognize the name, so I Googled it and called her.”

Donna Levy told him she had been a student at Emek 40 years ago. Her family had had little connection to Yiddishkeit, and Rabbi Stepen accepted her as a student for free. “I always wanted to pay back the tuition my family wasn’t able to pay,” she told Rabbi Shifman. “This is the first installment.”

Donna continued, “Rabbi Stepen’s daughter Sarah was in my class, and once she invited me to join them for Shabbos. My family didn’t understand what that meant, so my father drove me to their house on Saturday afternoon, and I came in wearing shorts and a T-shirt. But nobody blinked an eye. Sarah took me to her room and lent me a dress, and the family made me feel completely welcome and comfortable. It left a tremendous, everlasting impact.”

With Rav Pam ztz”l. There was no question too “small” for daas Torah

Kidnapped Rebbi

Rabbi Stepen’s success was due in large part to his unique combination of authority and warmth. “He could command respect while playing baseball with the kids,” recalls Johnny Istrin, a former talmid.

His daughter Sarah adds, “He was extremely frum and learned, while at the same time he was so normal and fun. I taught at Emek for two years, and in other schools for another 30, and there was no principal like him. Everyone loved him, but you didn’t mess around.”

When Rabbi Stepen first came to Emek there was no Gemara rebbi for the eighth-grade boys, so he taught eighth grade Gemara. Dubby Teichman, whose parents Sol and Ruth Teichman were devoted partners in building the yeshivah, as well as dear friends of the Stepen family, remembers that he’d heard at home that the new principal was a strict administrator. When he found out Rabbi Stepen would be his Gemara rebbi, he told his classmates, “Oh boy, we’re in for it.”

When they came into the classroom, they found a message from their new rebbi on the board: “Open your Gemaras to the page and be ready.”

When Rabbi Stepen came into the classroom, deliberately five minutes late, he found the boys jumping around the classroom. “What? Can’t you read?” he scolded. “Open up your books and put your fingers on the place!”

“We all got scared,” Dubby says, “and we followed instructions. Then he said, ‘Got it? Okay, now follow me!’ He led us to his car, which was a six-seater, and somehow managed to pack all of us inside. Then he brought us to an arcade for four hours. When we got back, he said, ‘Okay, now we’re going to learn.’ He won us over, and we never forgot it.”

Tabitha Dror began attending Emek in the early 1980s, transferring out of Kadima, a school with Conservative affiliation. “My family wasn’t so religious,” she says, “at that time the public schools had started busing in inner city kids to local public schools, and after sixth grade [when students graduated Kadima, which only went up to sixth grade] most parents put their kids in public school. But some parents got nervous and looked for other options. Emek was the closest school to us, and while it was Orthodox, many of the kids were not. It was a real community school.”

Tabitha entered Emek and became best friends with Sarah Stepen. She was drawn to the Stepen family like a moth to a flame. She began spending Shabbos with them and even went with them on family vacations. When it was time to move on to high school, Rabbi Stepen convinced Tabitha’s parents to send her to Bais Yaakov, and they acquiesced.

“Rabbi Stepen was like a second father to me,” she says. “I owe my life to him. He ruled the school with an iron fist, yet with such kindness.” She later paid it forward by teaching in Emek for seven years, until she and her family moved out of the neighborhood. Now her daughter teaches there.

Dr. Josh Penn remembers that he and his buddies Dubby Teichman and six others in their class felt like big shots when they became eighth graders. Intoxicated with their senior status, they decided to plot a prank: They were going to kidnap the principal.

After planning for weeks, they were ready. They got to school early, before the other students, but after Rabbi Stepen had arrived. They locked the front gates with their bicycle chains, ran into Rabbi Stepen’s office, and handcuffed him. Then they waved a note in front of him crafted from cut-out letters from magazines that said, “We kidnapped the rabbi!”

“Rabbi Stepen just smiled at us and asked, ‘So what’s your plan?’” Dr. Penn recounts.

“We answered, ‘We kidnapped you!’

“ ‘Yes, you did!’ he answered. ‘So tell me, who are you going to give the note to? And how long are you planning to keep me?’ ”

“He was so disarming. He asked us questions without any anger, in a nice way, as if he were part of our team. ‘Do you think this note will fool the FBI?’ he asked. He left the cuffs on and walked around to show everybody. After that the whole thing just sort of evaporated.”

Dr. Penn also remembers when Rabbi Stepen decided to introduce Thursday night mishmar to the school. No one had any idea what that meant. The first Thursday, he brought out games and Danishes and had a little party with the boys. This went on for a few weeks. At their fourth meeting, Rabbi Stepen proposed, “Let’s do a pasuk.” Little by little he got the older boys learning Mishnayos and the younger ones learning Chumash.

Rabbi Eliezer Stepen quotes his father’s often-repeated maxim, “A rebbi will give his heart, and a child will give his mind.”

“He really was the best rebbi ever,” his son says. “He was my role model.”

While the school consumed the lion’s share of Rabbi Stepen’s energy and time, he made sure to take time off each summer for a family vacation. He loved nature, the outdoors, and water, and would take his children on boats or waterskiing at places like Lake Tahoe. “During that time he was completely focused on us,” says daughter Mirie Lazar. “He made it so fun, so memorable.”

With a group of about a dozen core families who banded together to launch a school, Rabbi Stepen led the way to what would become a vibrant Torah community. (Sitting L to R): Sol Teichman, Eric Schwartz, Rabbi Stepen, Dr. Sylvain Silberstein; (Standing L to R): Michael Shiffman, Larry Tover, Alex Pollack, Gabe Rosenberg, Unidentified, Irving Rubinstein

Dreaming Big

Rabbi Stepen took the reins at Emek in 1973, not long after the 1971 earthquake. “He was the earthquake that would shake up the community in the Valley,” says Johnny Istrin. At that time, the Valley’s tiny frum community was still a work in progress.

“Even the people who considered themselves frum at the time were not so frum by today’s standards,” Rabbi Shifman says. “In the earliest years, for example, the annual banquet had coed seating and mixed dancing. When Rabbi Stepen came in, he called Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky and asked, ‘What should I do? Should I resign?’ But Rav Yaakov told him he would catch more flies with honey. He should take the job and try to change things.”

With his prodigious energy — this was a man who woke up at 3:30 every morning to learn — he rolled up his sleeves and did whatever needed to be done. Rabbi Stepen separated the boys and the girls, a move he could make only because of his personal diplomacy and powers of persuasion. While a third of the students entered with no Jewish background at all, he insisted on running the school at the highest levels of frumkeit. His intention was that after eighth grade all his alumni would go on to Jewish high schools, and he eventually founded the Emek High School.

“He changed the model of teaching in the Valley. Before, if you were Israeli, they’d make you a teacher,” Johnny Istrin says. “Rabbi Stepen brought in real rebbeim and teachers.” Among the young rebbeim were Abie Rotenberg, Yussi Sonnenblick, and Gershon Kramer.

Dr. Penn adds, “He raised the level of limudei kodesh, but he also knew how to hire English teachers. The two best teachers I ever had were at Emek, in chemistry and English. He knew how to hire, and even though the salaries were low, they stayed because Emek was such a fun and inspiring place to teach at.”

Rabbi Stepen sent his own children to Emek after verifying with Rav Moshe Feinstein that it was the right move, and made it a condition of hiring: that his rebbeim also send their children to Emek. Despite the very diverse backgrounds, Rabbi Shifman says, “His own children would remain students of Emek, and the result was that b’siyata d’Shmaya all his children grew up very shtark.”

“He thought if he sent his kids elsewhere, people would think he didn’t think Emek was good enough, and they’d send to public schools,” says Rabbi Eliezer Stepen. He had no fear that the less-religious kids might be a bad influence on his own children. They were always allowed to invite friends over; Sarah remembers being sent to sleepover parties at the homes of non-religious classmates with a bag of kosher food.

Rabbi Stepen actively recruited frum families to the community. He built a beis medrash room for people to gather and learn, and brought in new frum families. Rebbeim and kollel yungeleit joined the community, all of which did much to change the face of the Valley. “Before that, the Valley residents were at most traditional, or Holocaust survivors,” Johnny Istrin says.

“The frum families he brought in gave people a notion that there existed such a thing as a ben Torah, that it’s not something reserved for the rabbi,” adds Dr. Penn. “He injected a frum feeling into the Valley.”

Soon the yeshivah began outgrowing its premises, and with his “partners in crime” — balabatim like Sol Teichman, Larry Tover, Dr. Sylvain Silberstein, and Alex Pollack — Rabbi Stepen envisioned and planned Emek’s expansion.

In the early 2000s, they set eyes on a piece of land off the highway. It had a school building that was no longer in use, adjacent to fields owned by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. While it was about two-and-a-half miles from the original school building in the East Valley, it was closer for the population of the West Valley, which was now starting to send to Emek as well.

“Rabbi Stepen went to Washington, D.C. to meet with politicians, and secured the necessary zoning approvals, as well as a very favorable financial deal to lease the property off the 405 freeway,” says Dr. Sylvain Silberstein, a close friend and board member for many years. “The old school building was still on the site, and Emek used it, plus some trailers across the road until our beautiful new state-of-the-art building was finished. Rabbi Stepen wanted the building to be a showcase, a product that non-frum families could relate to.” The fields, which couldn’t be used for building, were leased from the Army Corps of Engineers and provided the school with sports fields. That addition gave Emek the largest campus of L.A.’s Jewish schools.

“He designed everything with precision, basing what he could on Chazal,” Rabbi Shifman says. “The beis medrash was his pet project. It was on the top floor with 12 windows all around.” The current building can accommodate 1,000 students; enrollment is now at about 950.

“Not many people can be dreamers or visionaries and also keep a finger on the financial pulse,” comments Dr. Silberstein. “But Yochanan knew how to squeeze a dollar for the benefit of the yeshivah.”

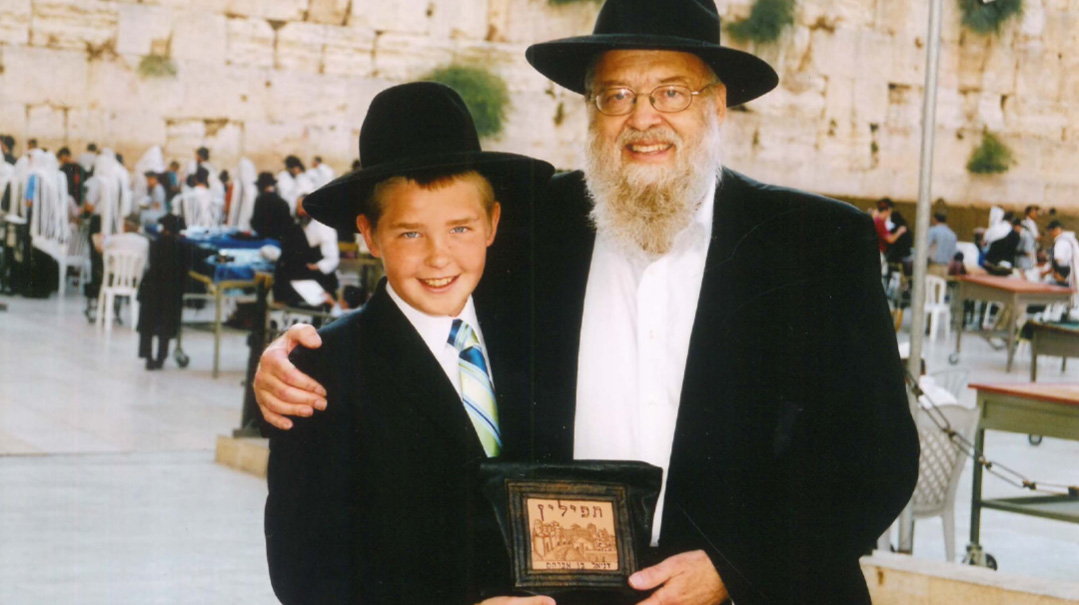

At his grandson’s bar mitzvah. Rabbi Stepen insisted his own children remain at Emek, and they all thrived in the mix, growing to create proud Torah homes

Lasting Legacy

Rabbi Stepen was able to inspire others because he himself was so passionate about Torah, a true talmid chacham whose enthusiasm was contagious.

He revered gedolim and never hesitated to call them. “He used to call Rav Moshe Feinstein about everything,” Rabbi Eliezer Stepen says. “We would have a brachos bee in school, and he’d call Rav Moshe with a list of all the brachos sh’eilos. After Rav Moshe was niftar, he’d call Rav Yaakov or Rav Pam. He once went to Rav Shach with a list of 100 community sh’eilos and sat for an hour, writing everything down. He had tremendous emunas chachamim.”

In fact, he continues, his father had always hoped his eldest son would take over the leadership of Emek. But Rabbi Eliezer was still in Eretz Yisrael, learning well, and was loath to leave. Rabbi Stepen went to Rav Chaim Brim, who knew his son well, and asked if he should push his son to return to the Valley. “Rav Brim said I should stay, and after that he pivoted 180 degrees,” Rabbi Eliezer says. “A gadol had ruled that I should stay, so that was that.”

At age 59, Rabbi Stepen announced his intention to retire and move to Eretz Yisrael, where he would learn full-time and be closer to the three of his five children who had settled there. “He always dreamed of going back,” Dr. Freddy Stepen says.

Yet a frightening diagnosis soon halted his plans. He spent the next year at home or in the hospital, continuing to work even while in treatment. Many didn’t think he’d make it; the aides who helped him out at home couldn’t believe that he survived and thrived afterward. “He could barely attend his youngest daughter, Rivkie’s, chuppah,” his brother says.

Following a miraculous recovery, he and his wife made aliyah, settling in Jerusalem. Rabbi Stepen would tell people his cancer was the gift that allowed him to retire and move to Eretz Yisrael. There he would spend the next 17 years, reveling in Torah study and life in the Holy Land, learning with his son Reb Eliezer in the kollel he became nasi of. He also had chavrusas round the clock, including his brother and his and son-in-law Rabbi Aryeh Haberfeld.

“He saw it as the best part of his life,” his wife Chana says. He spent hours with his grandchildren, in person and on the phone, telling them stories and listening intently to all the details of their lives.

He also had a “Dovid and Yonasan” kinship with his younger brother Freddy. Dr. Fred, who had a thriving dental practice on Roxbury Drive in L.A., left the working world behind and followed Reb Yochanan to Eretz Yisrael, settling in an apartment directly below him in Rechavia. Thanks to his brother, Freddy has been learning for years in an English-language kollel, making up for lost time.

“People used to thank me for physically shlepping my brother to the Gra shul every day, and to doctors, but in truth Yochanan was actually carrying me so much more… in ruchniyus,” Freddy says.

Rabbi Stepen, who had many health issues, developed diabetes, which affected him badly, damaging his hearing and his heart. His eyes weakened, too, and a supporter got him a special magnifying glass to help him read.

His kidneys declined, and during the last years of his life he required dialysis, but he never stopped learning. He would spend those hours learning with chavrusas. “Yochanan pushed himself beyond his limits,” Freddy says.

Rabbi Stepen called Rabbi Shifman to ask that the Emek talmidim daven for him, but related joyously, “In 40 years my learning has not been this good! It’s like the dialysis is taking the toxins out of my mind and helping me think more clearly.”

“Yochanan had an aura about him,” his brother says. “Sometimes he’d be walking on the street in Yerushalayim, and the garbage men would ask him for a brachah. He just had a special spiritual presence.”

After he contracted an infection, his neshamah left this world on Erev Yom Kippur four years ago. He was buried on Har Hazeisim, and his family sat a very brief shivah. His son Reb Eliezer renamed his kollel in honor of his father, Kollel Zichron Yochanan. His son-in-law, Rabbi Aryeh Haberfeld, named his kollel Emek Halacha, in honor of his father-in-law’s legacy, Emek Hebrew Academy.

Rabbi Yochanan Stepen had once contemplated being a pediatrician or a heart surgeon, and from a spiritual point of view, he was. He worked with children, dedicated to their spiritual health above all. He touched the hearts of countless people and restored a Jewish pulse to the community of the Valley. The medical profession’s loss became an infinite gain to the thousands of neshamos ignited by his fire.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 979)

Oops! We could not locate your form.