Hidden Layers

Strip away the where-what-when-how of our lives, and you’ll often find that behind the trappings of our modern-day routines lies a layer from the past — an ancestor whose life mission informs and impacts our own

Man Has to Do

Rabbi Avi Schnall

Eliezer Glueck left the when, if, and how to G-d, but he knew he had to take action. In the halls of government today, I walk with the same realization

Like so many other Holocaust survivors, my grandfather, Eliezer (Loychi) Glueck came to America without a penny in his pocket. A farmer’s son from the Hungarian town of Rakamaz, he spoke no English and had never been exposed to any sort of higher education.

With his mix of determination, optimism, and a steady supply of siyata d’Shmaya, this immigrant became vice-chairman of Maimonides Hospital, president of Bikur Cholim of Boro Park, and a member of the board of trustees of Agudath Israel of America.

I grew up in America, I speak English, and I get the culture and nuance of American life, yet it’s still hard to get things done, to accomplish. I spend a good part of my day in government offices, seated across from well-meaning people who look at me and say, “What you’re asking for is too hard,” or, “It will never happen.”

I think about how my grandfather, by then a United States citizen, was trying to get his own father out of Austria, but the proper papers were difficult to obtain. My grandfather flew to Austria, headed to the American consulate, and insisted that they give his father the necessary documents. The conversation got heated, intense. Suddenly, a set of wooden double doors opened and my grandfather saw Vice-President Richard Nixon, in Vienna on a fact-finding mission.

Rabbi Avi Schnall is the New Jersey director of Agudath Israel of America.

(Excerpted from Linked, Succos 5780)

In the Genes

Goldie Hauer

Renee Reichmann left the Reichmann women a precious legacy — when something has to get done, do it

Some families seem to have a certain distinct trait, talent, or proclivity that spans generations. I sometimes wonder: Are those dominant traits the result of family culture and values, or are they actually handed down in our genetic code?

My grandfather Shmaya (Samuel) Reichmann stood for emes — absolute honesty in all his business dealings. My father, Moshe Reichmann, along with his brothers, continued in his footsteps. It was well-known in business circles that “their word was their bond,” and their signatures were worth more than a bank guarantee. That scrupulous honesty has become a family hallmark. Is it because his descendants emulate him, or is it just in our DNA?

My grandmother, Renee Reichmann, was unusual for women of her era; she was a fiercely independent powerhouse and a great activist who used the resources at her disposal to save other Jews. During the war years, my grandparents stayed a step ahead of the Germans: They fled Vienna for Tangier, Morocco, when they realized the looming danger. From Morocco, my grandmother helped smuggle food to Jews in concentration camps within Europe, using the Spanish Red Cross as a conduit. In 1944, she battled to get visas that would allow Jews to come to Tangier. Thanks to her determination, courage, connections, and refusal to be cowed, she managed to save 1500 lives.

Today, I look at the women in our family and can’t help but notice a certain strength and sense of responsibility that so many of us share.

We Reichmann girls are independent, strong, and not afraid to be vocal, and when something has to get done, we step in and do it. You can see it in the younger generation too. I really believe that there’s something in our genes, something that was transmitted from the strong woman my grandmother was.

There’s something else that our family has absorbed — we cherish the mitzvah of kibbud av v’eim. Every single day, between eight to eleven p.m., my siblings and I visit my mother. Rain or shine, simchah or carpool, each of us will drop in. Why is this the most natural thing to us? Because growing up, we watched our parents do the same for their parents.

We don’t always realize that with the decisions we make and the values we act on, we’re creating a family legacy. It’s only years later, when you see children and grandchildren with the same trait and principles, that you realize what you’ve received and given over.

Goldie Hauer is an active member of the Toronto community.

(Originally featured in Linked, Succos 5780)

The Lost Boys

Rabbi Yitzchak Elkayam

My grandfather gave young Sephardim entrée to the elite yeshivah world. I knew I had to give my struggling friends something eternal too

Four years ago, I ran into an old yeshivah friend — a meeting that shook me to the core and propelled me to take action. My friend Shaul had been a top bochur in Chevron back when we learned there together, and had eventually left kollel and went to work to support his family. I was happy my friend was making parnassah, but when I prodded further about his learning sedorim, Shaul admitted that he no longer spent any time in the beis medrash. Shaul had no idea how to juggle some kind of learning framework with his new life. He’d been a top yeshivah bochur and was used to intense learning, so he didn’t feel comfortable joining a shiur for balabatim — yet he had no realistic way to retain his footing in the beis medrash. He had lost his place.

He told me how he rarely learns anymore, how he davens Shacharis in a local shtibel, goes to a Carlebach minyan on Friday night, and Maariv is in the parking lot. Basically what he was saying is that he had no kehillah to call his own. I began investigating and discovered that Shaul wasn’t alone. He was a statistic — because in the yeshivah world, the emphasis is on learn, learn, learn, and when an avreich leaves that framework, he hasn’t been given the tools to make the bridge, how to remain a serious ben Torah while bringing parnassah to his families, how to avoid the irresistible pull of the working world that can suck you in like a vacuum cleaner.

I was still entrenched in the yeshivah world, and knew I had to take some action for this chevreh, but how? Then, in a flash, I remembered my grandfather, Rav Nissim Toledano ztz”l, and his mesirus nefesh for Torah. He passed away seven years ago, but I grew up on his knee and knew I could tap into what I learned from him.

Rabbi Yitzchak Elkayam lives in the Jerusalem suburb of Har Shmuel, where he’s a popular daf yomi maggid shiur. He is the founder of Itim, which runs kollelim for working men in Jerusalem and Beitar.

(Excerpted from Linked, Succos 5780)

Same Goal, Different Tools

Nachi Gordon

Reb Nison Gordon utilized the printed word to advocate for the younger generation. I utilize our era’s tools to reach today’s teens

Inever knew my grandfather, Reb Nison Gordon, but from when I was young, I would say my last name with pride, knowing there was a good chance it would be met with the enthusiastic inquiry: “An einekel of Reb Nison?”

My grandfather was wise and he was courageous and he was perceptive. He was opinionated too; his newspaper columns influenced a generation of readers of the Algemeiner Journal.

But there was something else about him that impacts me every single day. Independent as he was, he was a devoted chassid to his rebbe, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, genuinely submissive to the Rebbe’s vision and ideas. For an opinion writer, it’s almost an anomaly to be that deferential to someone else’s view.

Today, I do something far different than what he did, but in a strange way, I feel like it’s very much the same. Meaningful Minute, my program of daily inspirational clips, has a massive following on social media, our events have drawn thousands of people, and the book has changed so many lives. I’m no writer, nor am I an intellectual like my grandfather, but I’m trying, in my small way, to use the tools of our generation to inspire others.

Nachi Gordon is the founder of the “Meaningful Minute” inspirational clips.

(Excerpted from Linked, Succos 5780)

Plants and Roots

Rabbi Yehuda Eisenberg

With passion and resolve, Rav Yitzchok Yechiel Yakobovitz inspired respect for tradition. As I interact with politicians and policymakers, I try to speak to the souls inside

We’re still in the year of mourning for my grandfather, Rav Yitzchok Yechiel Yakobovitz, the chief rabbi of Herzliya. He served in the position for 66 years, the last of his generation in that role.

My grandfather was a close talmid of the Chazon Ish, who sent him to assume the rabbanus in what was a largely secular town. Those rabbanim who’d been influenced by the Chazon Ish had a particular sensitivity to the halachos of shemittah, and the general halachos pertaining to the sanctity of the land. My grandfather was no different. He worked with secular politicians and city council members over the years, impressing upon them the sacredness of their mission, the glory in treating the Land with respect and awe.

On the eve of the last shemittah year of his tenure, the climate was heavy with anti-chareidi sentiment and claims of religious coercion, but my grandfather was undaunted. At summer’s end, he met with the mayor and made it clear that the town would be respecting the laws of shemittah. The mayor acquiesced.

Yehuda Eisenberg is a member of the executive council of Degel Hatorah of Bnei Brak

(Excerpted from Linked, Succos 5780)

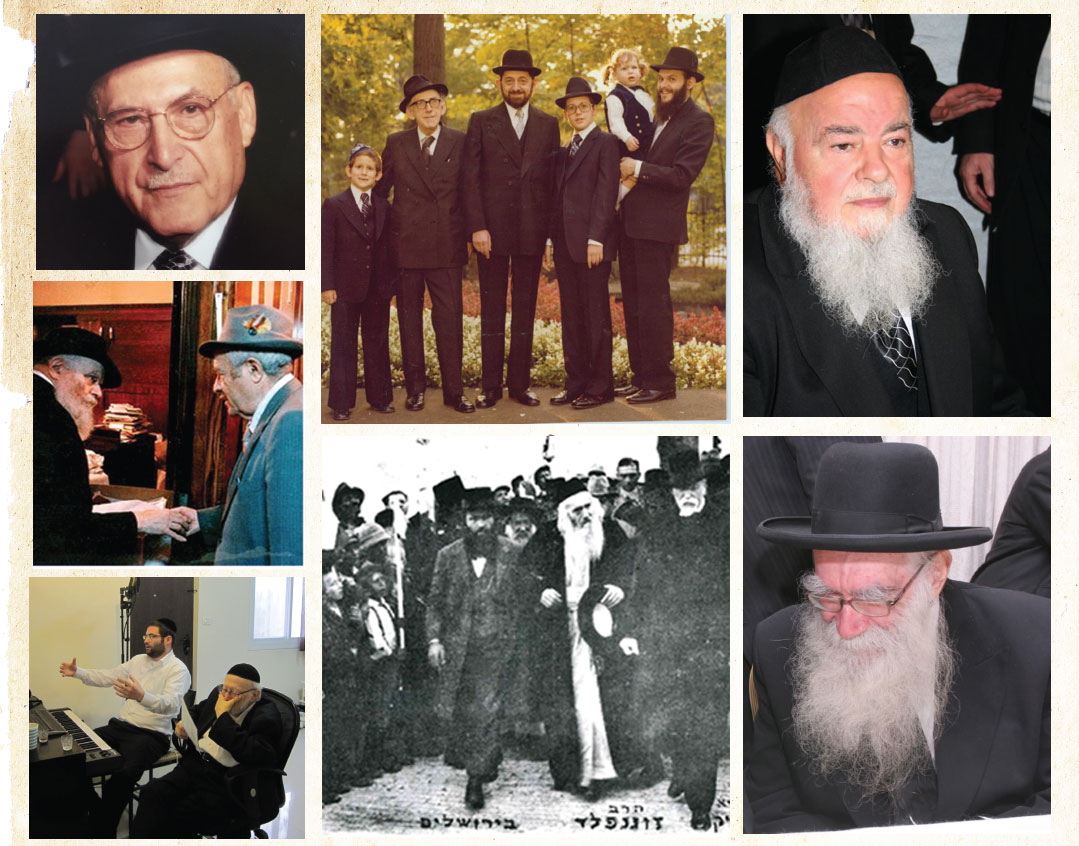

Pillar of Passion

Rabbi Mordechai Besser

Rav Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld suffered poverty and indignity for bigger causes. I draw on his strength to face my own challenges

Even as a little boy, I knew that it was both a privilege and responsibility to be a great-grandson of the famed rav of Yerushalayim, Rav Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld.

My great-grandfather was known for his zealousness and fierce battles for the authenticity of the mesorah. Less known are his peacemaking efforts between local Jews and Arabs. His was the voice of moderation, and when he would walk between his home and shul, the local Arabs would rise in deference.

Rav Yosef Chaim’s public disagreement with the ideology of Rav Kook is legendary, but their close personal friendship is less well-known. When Rav Kook traveled to the Northern Galilee on an outreach mission, he asked Rav Yosef Chaim to accompany him.

When it came time to marry off his daughter, Rav Yosef Chaim chose my zeide, a Belzer chassid, talmid chacham, and successful businessman. It says a lot about the nuance, color, and vision of the Yerushalayimer Rav.

Rabbi Mordechai Besser is an executive school consultant for Torah Umesorah

(Excerpted from Linked, Succos 5780)

Musical Inheritance

Yitzy Berry

Chassidishe niggunim and chazzanus are both part of my family's musical heritage — a legacy i try to tap in my own compositions

My partner Eli Klein and I work together in the music business, and we offer a one-stop-shop service ranging from composition to lyrics to producing, arranging, mixing, and mastering. I’m fortunate to work with many of today’s popular Jewish singers who sing my songs, and they all assume they know where the talent comes from. After all, my father is the famous “Suki” of the Suki and Ding collaboration; he’s an incredibly gifted arranger and composer whose music accompanies some of the most famous singers in the Jewish world. (In fact, that’s only a side job — his real calling is as the mashgiach of Yeshivas Imrei Binah.)

Those who know me a bit better might know that my mother plays her own role in this musical story. She’s a gifted guitarist and lyricist who composed Avraham Fried’s classic “Hashem’s the World” and some early MBD songs.

But really, my musical history goes further back.

Yitzy Berry is a composer, arranger and producer of Jewish music.

(Excerpted from Linked, Succos 5780)

All the Children

Rabbi Menachem Leifer

Growing up with the last name Leifer, we were immediately associated with the holy dynasty of Nadvorna, which stretches back to Rav Meir Hagadol of Premishlan, a talmid of the Baal Shem Tov.

It’s likely that the dynasty spawned more rebbes than any other, giants of spirit and learning. Among the Nadvorna descendants, it was customary for rebbes to move away from large communities and settle in small towns, bringing the light of chassidus to people who wouldn’t have been exposed to it otherwise.

In America as well, cities like Newark, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland became associated with chassidic dynasties because of that influence.

But just as I grew up proud, I grew up with humility, because I knew I was so far from emulating the greatness of my zeides. I resembled them not in learning, not in avodah, not in middos, and not in kedushah. I was so far from them.

After my wedding, my wife and I were blessed with one special-needs child, and then another. Living in Kiryas Tosh, near Montreal, we were at the mercy of the Quebec health system and there were few options for our children. It looked like we would have to move to New York, where there were more services and educational frameworks.

Then my wife made an innocent comment. “If we leave Canada,” she said, “it might help our children. But what about the next set of parents facing a similar challenge? How will it help them?”

Menachem Leifer Is the Founder of The Donald Berman Yaldei Developmental Center of Montreal

(Excerpted from Linked, Succos 5780)

Oops! We could not locate your form.