He Speaks Your Language

Rabbi Reuven Kamenetsky aims to bring an Anglo voice to Jerusalem’s city council

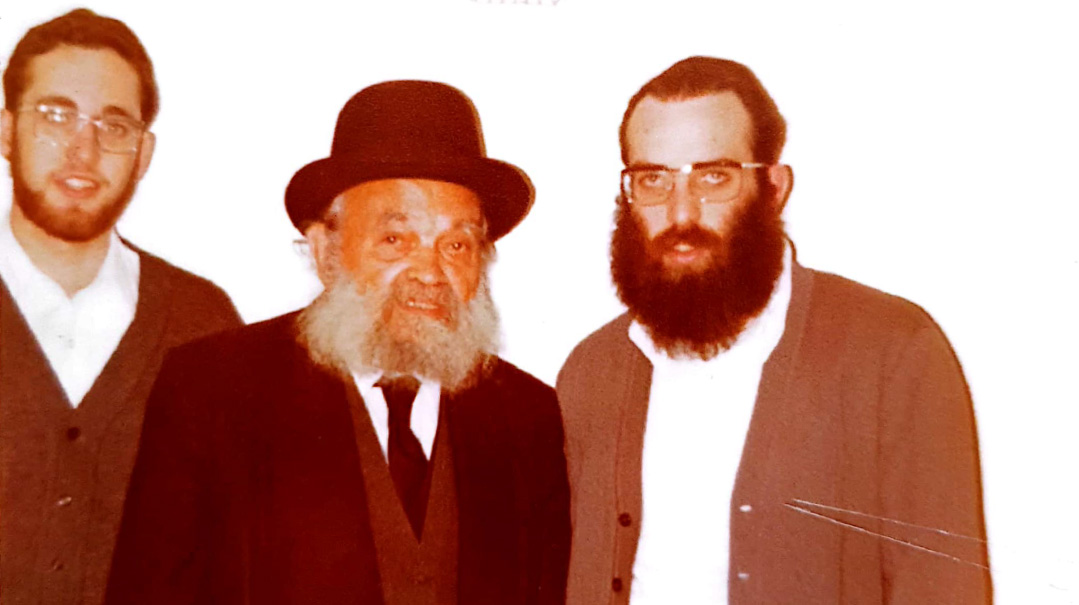

Photos: Shmuel Dry

When Rabbi Reuven Kamenetsky took charge of running the nascent Degel HaTorah office founded in the late 1980s at Rav Shach’s behest, he didn’t dream that decades later he himself would run for office. But Jerusalem’s changing demographics call for varied representation, and ever the public servant, he’s agreed to answer the call

The headquarters of the Degel HaTorah party in Jerusalem are surprisingly quiet, considering that municipal elections are scheduled to be held next Tuesday. Maybe that reflects the mood of the country in general — a certain antipathy to holding elections during wartime. But the same phenomenon that’s disrupting the country’s newfound fragile unity on the national level is visible on the local level too, as the pettiness of politics rears its head again. Besides, the law mandates municipal elections every five years — and it’s necessary for the year’s budget to be ratified.

Here, in the headquarters of Degel, which garnered six of 31 city council seats in the last election, there are more offices than people around, although every wall is plastered with the flags of the political party that represents the litvish chareidi community. The slogan for this campaign is “Kulanu” (“all of us”) which might help explain the decision to place American-born Rabbi Reuven Kamenetsky on the slate and lend some credibility to that promise. (MK Rabbi Yitzchak Pindrus, former Jerusalem deputy mayor through Degel HaTorah, is also an English speaker who helped this sector within his municipal role, but he was born in Jerusalem and never identified as “one of the Americans.”)

Reb Reuven, grandson of Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky and son of Rav Noson Kamenetsky, zichronam livrachah, is a Torah scholar and teacher of note in his own right, now likely to become the first chareidi American to join the Jerusalem city council. His placement in the seventh position on Degel’s list — hopefully a safe spot — symbolizes the hope that the substantial English-speaking population residing in Israel, and in Jerusalem in particular, may finally begin to have its own representation.

An additional seat on the Jerusalem municipality should award Degel greater decision-making power over the 12 billion shekels (approximately $3.3 billion) comprising the city’s annual budget. Currently, 31 seats are up for grabs, with Degel HaTorah holding the largest bloc (six) in a council that’s fragmented, but whose unity among religious and right-wing parties (such as Shas, Agudas Yisrael, and Likud, among others) nearly guarantees the reelection of the current mayor, Moshe Lion.

While some of the most hotly debated municipal issues revolve around the city’s structural development, such as expanding the light rail or issuing permits for high-rise towers, the issues of particular concern to the religious community include the budget allocated for education, expansion of tax discounts on housing, and construction permits that could facilitate cost reductions in housing.

The presence of an English speaker on the city council entails much more than mere demographic representation. While citizens in Israel have access to many benefits, anyone who has dwelled in the Promised Land knows that many services aren’t easily distributed: Most of the time, you have to go out and fight for them.

For example, all residents of Jerusalem have the right to send their children to a municipal preschool that suits their needs, and they can even request enrollment in an English-speaking one, a family whose father learns full time and has a low income is entitled to a discount on property tax (arnona), and any family with a special-needs child qualifies for appropriate education and services... as long as they can navigate the bureaucratic and language barriers. While the services are there, many English speakers don’t even bother to claim them, or, worse, opt to pay for private services despite being eligible free of charge to public ones, simply because the process is arduous, mazelike, and confusing. That’s one thing a chareidi English-speaking council member would aim to resolve.

Rabbi Kamenetsky is quick to assert that the need for an English-speaking voice capable of making decisions in a city like Jerusalem is not a favor but a right held by the tens of thousands of English-speaking individuals who call Israel’s capital their home. Moreover, on a personal level, he feels that by entering the political arena, he is, in his own way, following his family’s legacy. “If I would have gone to my Zeide and asked him if I should do it,” he says, “I’m sure he would have said to go ahead.”

When Reuven Kamenetsky was a child, his family’s frequent moves forced him to change schools six times — three in Israel and three in the United States. “I hadn’t even finished learning the names of my classmates before it was time to bid them farewell,” he recalls as we sit together in the Degel HaTorah bunker. But what is now the subject of jest was a challenging experience during his youth. In his home country, he was seen as an “Israeli,” while in the Promised Land, he was viewed as an “American.”

He probably never imagined that at the age of 62, this very challenge would become the winning card for his candidacy for the city council. “Because of my background, I can bridge the gap between the American mentality and Israeli politics,” he asserts.

Given his illustrious surname — his grandfather was one of the great disseminators of Torah in America, and his father was founder and rosh yeshivah of Yeshivas Itri (his mother is the daughter of Rav Dovid Lifshitz, the Suvalker Rav and rosh yeshivah of RIETS) — one might have assumed that his destiny was to become a rosh yeshivah as well. But Reb Reuven insists that serving the community is also very much a part of the Kamenetsky legacy. “I saw from my grandfather the importance of public askanus. And, together with his gadlus in Torah, of course, he exhibited tremendous mesirus nefesh to serve the public within the framework of Agudath Israel in America. And I saw how important he felt it was to vote in Eretz Yisrael.”

Although he’s now stepping onto the grand stage of politics, Reb Reuven’s entry into the arena dates back over 30 years, and it was primarily a response to the call to assist the chareidi world. After studying at Yeshivas Itri, the recently married Reb Reuven and his wife Rivka (née Teitelbaum) settled in the then-fledgling neighborhood of Har Nof. “I was one of the pioneers in Har Nof,” he remembers. “There was a bus once an hour, and we bought bread and milk from the back of a truck. And you could never get a cab to Har Nof. The driver would say, ‘That’s the end of the earth — I’m not taking you there!’”

Rav Reuven was a young avreich back in 1988, when Rav Shach founded the Degel HaTorah party and called upon all bnei Torah to support the new party’s electoral campaign. “When it started, everyone tried to help. Most people back then went out to knock on doors, trying to convince people to vote for this new party. I wasn’t so much into knocking on doors, so I said, ‘You know what, I’ll run the office.’ And you know how it goes: As the years passed, people stopped knocking on doors, but I continued running the office.”

Rabbi Kamenetsky soon found himself the linchpin of Degel’s municipal campaign. “It means that right now, I have 35 people working under me in every neighborhood of the city, in charge of identifying Degel voters and making sure they come out to vote on Election Day.”

But until now, his Degel duties were confined to election periods, which meant he could essentially devote his time to the Torah career that was his primary calling. After studying in kollelim for several years, he served as a maggid shiur for 23 years at Yeshiva Darche Noam–Shapell’s, and for over 30 years, he has been giving shiurim to English-speaking balabatim in Har Nof.

Over time, though, the Anglo community’s call grew louder. They knew that if they needed help with government bureaucracy, Reb Reuven was the person to consult. He — and the Degel leadership — soon realized the importance of having an English-speaking representative on the city council, and besides, he says, “the English-speaking tzibbur that votes for Degel is gigantic.”

Reb Reuven wasn’t the only one with this idea. In recent years, the growth of Jerusalem’s English-speaking chareidi population marked it as a sizeable and significant demographic, and many governmental and communal bodies found themselves providing support and assistance to the increasing influx of newcomers. During the previous municipal elections, in 2018, the “Anglo presence” proved itself not just a social phenomenon, but a political force as well.

“It became very clear in the last elections that a sizable chunk of Degel HaTorah votes were from English speakers,” says Rabbi Paysach Freedman, CEO of Chaim V’Chessed, the organization dedicated to guiding the English-speaking population living in Israel. “Just look at the schools — they’re filled with English-speaking families. And the younger the demographic, the more Anglos there are, because young Israeli couples generally leave Jerusalem for more affordable housing options.”

The primary challenges facing Americans living in Israel are really not such a mystery: They essentially boil down to two fundamental issues — the language barrier and access to information.

Rabbi Nechemya Malinowitz, director of Eretz HaKodesh, has for several years served as the liaison for the English-speaking community in Degel HaTorah. “Jerusalem has an impressive percentage of English speakers,” he says, “and Degel HaTorah has provided assistance and service to them for many years, but what it hasn’t been able to do so far is speak the language of Anglos. The services are there, but they’re not always accessible to the English-speaking community.”

It could be a mother who wants to switch her child’s gan, a newly arrived couple seeking to apply for a property tax discount, or a parent urgently trying to enroll a child in a school for children with special needs. That’s why Degel was so excited to put an American on its slate — not to provide “additional benefits” to the English-speaking community, but rather to ensure that they receive the same benefits as the rest.

It’s difficult to calculate the number of English-speaking residents living in Jerusalem because there’s no concrete definition. Is a person who was born in Monsey but has lived in Jerusalem for the last 30 years an “American”? And what about their children, who speak Hebrew fluently and identify more with the Israeli lifestyle? Still, Rabbi Paysach Freedman asserts that “between 10,000 and 20,000 Degel voters come from the English-speaking sector.” And it’s growing.

It takes about 8,500 votes to secure a seat on the city council, and while Degel captured six seats in the last election, the party is confident it will cross the seven-seat threshold and obtain a seat for Reb Reuven. Still, how much change can one seat make for such a large demographic? Degel is confident that Anglos will feel tangible benefits. According to Rabbi Malinowitz, this could be a litmus test to seek more American representatives in areas where these communities have demographic weight.

While Reb Reuven is certainly community-conscious, the last thing he expected was that he’d be asked to take the position. “This was not my focus,” he says. “I’m busy teaching Torah and learning. It’s true that I’m the one who pushed the idea of an Anglo member on the city council, but I wasn’t talking about myself. When Degel asked me to run for the seat, I begged Chevron rosh yeshivah Rav Dovid Cohen and Degel posek Rav Yosef Efrati to select someone else, but they wouldn’t hear of it. They said I was the right person for the job.”

And testimonies from Anglos who struggled to navigate the system reaffirm that the need for an English-speaking advocate is real. The Goldschmidts, for example, had been living in Jerusalem for four years when they encountered an issue with the arnona discount. While there’s some leeway to request an exception, a technical glitch in the system led to the rejection of their request. “We had no idea who to speak to and kept getting shuffled around,” Mrs. Goldschmidt says. “During the protracted back-and-forth, our bank account was frozen. It was a disaster — we barely knew the language, we were trying to navigate this property tax issue, and then we were locked out of our own money. Eventually, we managed to speak with an acquaintance of a neighbor who had ties to Degel HaTorah. They resolved it, but it took time and anguish.”

When the Berg family moved from Beit Shemesh to Jerusalem, in the middle of the school year, they had to change the children’s preschool arrangements. “Initially we were told that all the municipality-sponsored English-speaking preschools were full, and so for a while, we were shlepping them to a distant neighborhood,” says Mrs. Berg. “Eventually, we managed to connect with someone from Degel who facilitated the transfer to a center near our new home. Although we’re grateful, we’re left with the feeling that a lot of time was wasted simply because we didn’t know who to turn to. And when we saw how easy it was, we understood that knowing the right people was key.”

When the Rosman family made aliyah, they were advised to put their little boys into a “gan safah,” a special language-enrichment gan generally geared for learning-challenged youngsters. The problem arose when they tried getting them accepted into a mainstream school after that. “It was months of distress, and it made us wonder why we’d even come,” says Mrs. Rosman. “Finally, with a lot of Divine assistance, someone at Degel HaTorah helped us and pushed the municipality to compel the neighborhood schools to accept them. Baruch Hashem, we now have three boys in school, and we’re happy, but we wouldn’t want other families to go through those months of despair.”

One of the ongoing questions in Israeli society revolves around the ability — or interest — of foreigners to integrate with the locals. Many locals take offense when, for instance, they see Anglos conversing in English without, in their view, putting in the effort to master Hebrew.

“You can debate from today till tomorrow about whether English speakers should blend in more, how they should interact with Israeli society. But that has nothing to do with the need for an English-speaking member on the city council,” says Rabbi Freedman. “Ultimately, whether Anglos decide to integrate with Israelis or not is a personal choice. What should not happen is for this group, which pays its taxes, fulfills its obligations as citizens, and has the same needs as other residents of the city, to receive less than the rest.”

It’s basically a done deal that after the February 27 elections, Moshe Lion — a well-liked mayor with little competition — will be granted another five-year term as mayor. While Reb Reuven praised Mayor Lion’s administration, he still emphasizes the need for the chareidi public to turn out at the polls to vote for their own representatives. “There’s a very simple principle in Israeli politics: If you don’t get representation, you don’t get the services you need,” he says. “Of course, we aren’t looking for fights. We’re looking to preserve the status quo of Jerusalem, to protect the kedushah of Jerusalem, and to meet the needs of our tzibbur. We are not looking to take anything away from other communities. We recognize that there are other people out there. We aren’t looking to take away what they deserve, but it’s a fact that over the years the chareidi sector in Jerusalem has received less than it deserves, and all we want is fairness.”

The timing of these elections — against the backdrop of war — has added a decided note of discomfort to the usually spirited process. Many voices have criticized the political discussions at a time when young people are dying on the front lines and hostages remain distant from their families. Rav Reuven not only understands this sentiment, but even agrees with it.

“It’s true — we shouldn’t be thinking about elections now,” Rabbi Kamenetsky admits. “We should be focusing on learning more Torah and davening more. But, at the end of the day, although we aren’t asking for these elections, they are here, and if we want a positive outcome, we need to get out and vote.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1000)

Oops! We could not locate your form.