Growing Together

Rabbi Shimon Russell discovered his best self by parenting his struggling kids

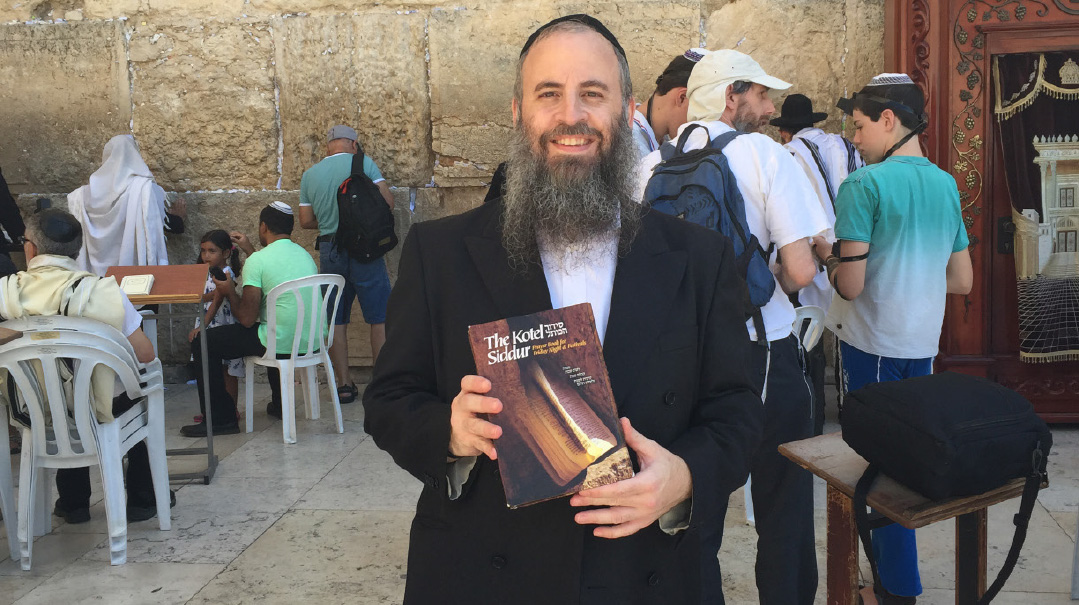

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Personal archives

E

very couple who sets out to build a Jewish home desires — and generally expects — to raise a loving family. But what happens when somewhere down the line, the dreams and fantasies implode, leaving parents scratching their heads in shock and bewilderment when their child’s behavior takes an unexpected turn? How can parents distinguish between rebelliousness and trauma, between malice and inner brokenness? And how can we expand our consciousness and stretch what we thought were our limits, instead of falling into the counterproductive trap of our own emotional triggers?

Rabbi Shimon Russell, an international authority on the phenomenon of young people who opt out of frum life and a longtime Lakewood mental health professional before relocating to the Jerusalem suburb of Givat Ze’ev, also wants to see us in healthy, supportive relationships. And he’s even given us a book to help us get there.

Drawn from Rabbi Russell’s talks and wisdom, Raising a Loving Family — written by author and educator Rabbi Zalman Goldstein — is not only a rich repository of foundational parenting psychology and practical down-to-earth guidance for creating loving and enduring bonds with our children; it’s about how to make kids feel they really matter, and how, by developing healthy parental attachments, to raise them in a way that even if and when problems and crises arise, they’ll have the resilience to weather the storms of trauma and other roadblocks in their young lives.

True, there are a lot of parenting guidebooks out there, and some are even Torah-based, but this one doesn’t talk at you, it talks with you and holds your hand. Because no one knows the complex challenges of today’s struggling youth and their overwhelmed, confused, and devastated parents like Rabbi Russell. He’s been there and back himself, on a journey he never wished for and never expected — but one that’s molded him into a person he never dreamed he’d be.

A Different Script

It was 1963, and the Russell family was driving through the streets of London on the way home from their zeide’s traditional Pesach Seder, when inquisitive nine-year-old Shimon, looking out the back window at the city’s sparkling lights, suddenly asked his father, “Daddy, why do we go to a Seder every year?”

Growing up in South London as a second-generation British Jew, Shimon’s father didn’t connect much with traditional Judaism. His mother, who had a religious childhood, drifted from much of her religious practice after being billeted by law with non-Jews during the Blitz of London during World War II. But some Jewish spark remained, because the family kept a kosher home, and the Russell boys attended religious Talmud Torah three times a week.

Shimon’s father could have ignored the question that Pesach night, but instead he answered his young son to the best of his ability: “Because we’re Jewish, because my father took me to his father’s Seder, and this is just what we do.”

“Does that mean it’s true, that we really came out of Egypt, and that’s why we’re passing down this story?” asked Shimon, repeating what he’d enthusiastically learned in Talmud Torah.

“Yeah, I guess that’s true,” said his father.

“So in that case,” asked Shimon, “why are we driving?”

“That was the last time my father put me in the car on Shabbos or Yom Tov,” Rabbi Russell recalls. “After that, my grandparents came to us for Pesach. It changed the trajectory of my entire family. Although my father continued to work on Shabbos until he retired, my brothers and I would walk three miles to shul every Shabbos and Yom Tov, and in honor of my bar mitzvah, I decided to become fully shomer Shabbos. By 18, I was in yeshivah in Eretz Yisrael, and my brothers followed — although my parents were a bit dumfounded how all that happened under their noses.”

(Years later, a widowed Mrs. Russell came to Lakewood to live with her son, having reclaimed her heritage, and she had such a regal bearing of faith and emunah that her new Lakewood friends assumed she came from a long line of Hungarian rebbetzins.)

After five years in yeshivah in Eretz Yisrael, on the advice of Rav Shlomo Brevda, Shimon and his new wife Yocheved moved to Lakewood, where — although he preferred to sit in the back and go unnoticed among the learning heavyweights — Rosh Yeshivah Rav Shneur Kotler showed great interest in him and gave him his personal semichah, the very last one granted before the Rosh Yeshivah passed away in 1982.

Reb Shimon’s plan was to learn full-time and eventually find a position as a rebbi or mashgiach. “But two seats away from me there was a guy who seemed to be in a severe emotional crisis,” Rabbi Russell relates. “I alerted everyone in yeshivah but no one paid much attention — until he took his own life. There were no mental health professionals in Lakewood then, and some of my chaveirim who were so shaken by this incident told me, ‘Shimon, you noticed, maybe you should go into this.’

“At first I thought they were nuts, but they wore me down, impressing upon me how I was always the baal eitzah and chizuk-giver when it came to emotional issues and conflicts. Soon I started wondering if, indeed, maybe I could be part of the solution.”

It wasn’t a decision he could make lightly though, so he flew to Eretz Yisrael to discuss his dilemma with Rav Elazar Menachem Man Shach. To his surprise, Rav Shach strongly encouraged him to enter the mental health field.

“We have many excellent candidates to be rebbeim,” Rav Shach told Rabbi Russell. “But we need more excellent mental health professionals in our world!” Rav Shach encouraged him to go to university, earn a degree, and get a proper license. And so, Rabbi Russell began studying at Rutgers University while under instruction from Rav Shach to maintain two full sedarim in BMG during the day, earned a master’s degree in clinical social work, and hung out his shingle in Lakewood, set to work as the town’s first full-time frum therapist.

Life was good, they began to build a family, and Rabbi Russell was busy and productive, working quietly out of his basement office. What he didn’t know at the time was that his oldest daughter had a subtle undiagnosed learning disability, which made school a daily nightmare for her.

Meanwhile, their second child, a twin whose brother was stillborn, came into the world with multiple acute medical issues, and the Russells had to rally to keep him alive and help him survive his childhood. In retrospect, says Rabbi Russell, while they were so focused on saving their son (today he’s married with two children), the other children in the family felt their parents were less attuned to their particular struggles, yet didn’t want to burden them with their own problems.

“In the constellation of all this, when our oldest daughter was 14, she slipped off the derech, which caught us totally by surprise. Maybe there were warning signs, but parents are often the last ones to see it coming,” Rabbi Russell relates. “Yet it was the catalyst that moved me from being a quiet, mediocre therapist going about my work to begin to understand in a real way the shattering sugya of OTD.”

Ultimately, he learned the painful sugya from several of his own children — six out of eight would find themselves struggling with Yiddishkeit over the next years in one way or another. Yet due in no small measure to the wisdom, bravery, and a “crisis chinuch” model Shimon and Yocheved Russell implemented, their children — now married with families of their own — were able to navigate the path back.

Those didn’t feel like years of glory or bravery, though. In fact, when their first daughter began to struggle, Rabbi Russell admits that “it shattered my confidence to the point where I considered stopping my work as a therapist. I felt that perhaps I was misleading people by pretending to be some kind of expert on struggling kids, when I myself felt I was failing as a father.”

He says it was the reflection of his own clients who were going through similar challenges that helped him regain his footing. “They’d heard I was struggling with a child too and felt that perhaps I could really understand how terrifying and challenging it was for them. And that pushed me to set out on a personal journey to try to be bigger than the challenges I faced and to learn what they were really all about.”

Zalman Goldstein and Shimon Russell were a good shidduch. People had been encouraging the renowned therapist to write a book for years, but he simply had no time

Love Beyond Defiance

One thing he learned was that he could be bigger than the pain.

He relates the aftermath of a Shabbos in Tzfas with one of his teenage daughters who was struggling with Yiddishkeit. “I thought that the great uplifting Shabbos we’d had together would inspire her to let go of some of the edgy things she was doing, but while driving back to Jerusalem, I saw that her clothes were just as inappropriate and the heavy metal music was blasting just as loudly.

“Halfway through the trip, I felt so much pain I had to stop the car. I pulled into the nearest gas station and walked into a nearby field. I called out to Hashem, ‘Help me, help me! Show me something I can hang on to — I feel so lost!’ And then the following words came into my head: ‘Try to defy me more than I can love you. You won’t be able to, because I love you unconditionally.’ I knew then and there that my daughter’s defiance would allow me to help her heal, because if I could love her more powerfully than she could defy me, then perhaps I could help her feel safe and start her journey to recovery.”

Rabbi Russell remembers how his wife was driving in Lakewood with one of their struggling daughters, who was dressed in jeans and a T-shirt. (“It was back in the early days, before so many families in Lakewood had one of these struggling kids,” says Rabbi Russell.) As they drove past an ice cream parlor, their daughter asked if they could stop and go in for some ice cream.

“My wife parked the car, put her arm around our daughter, and walked into that store filled with frum Lakewood customers,” Rabbi Russell says. “Later, a friend called her and told her what a chizuk it was to her to see my wife unembarrassed, with a loving arm around her daughter dressed like that in public.

“And what we started discovering was that so many people out there were struggling with their kids and were watching us, looking to us for their own cues. So I turned it into my own avodas Hashem.”

He learned that lesson again on one of the many trips he made to Eretz Yisrael to keep an eye on his daughter, who was in and out of programs there. It’s a story he repeats often, and even with the distance of two decades, it still makes him tear up. He relates how on the plane, he met up with two roshei yeshivah he knew, and after arriving at Ben-Gurion, the two roshei yeshivah walked out of customs together with Rabbi Russell to the arrivals hall.

“At this point, I hadn’t yet ‘gone public’ with the challenge I was going through, so these rabbanim knew nothing about my struggling daughter. And then as we came through arrivals,” he remembers, “I noticed a beautiful suntanned young woman with long hair and a little red dress coming toward me. I instinctively looked away, but a moment later, I realized it was my own daughter.”

Despite his mortification, he ran ahead of the roshei yeshivah to give her a big hug.

“I couldn’t even look back, wondering what they must have been thinking,” he continues. “Although in the cab on the way to Jerusalem, I asked my daughter, ‘So, how did I do? Did I pass the test?’

“She said, ‘Tatty, you did great.’

“That Shabbos, I ran into one of the roshei yeshivah, and I was still pretty embarrassed. But then he put his arms around me and started crying, and I realized I was holding him up from collapsing. When he finally pulled himself together, he said, ‘Shimon, if I had your strength, maybe my son would come back.’

“The challenges our kids pushed us through took us to a place of authenticity and humility,” Rabbi Russell acknowledges. “Our frum world has unfortunately created an illusion of perfect families, which often just serves to promote anxiety and fear, but my kids gave me the gift of a truly authentic life, pushing me in my ruchniyus to places I’d never have gotten to.”

More than You Took

Some of us might remember the famous 1999 “Kids on the Fringe” issue of the Jewish Observer, including articles by Rabbi Russell, Dr. Norman Blumenthal, Rabbi Yakov Horowitz, and Dr. David Pelcovitz. For the first time, the phenomenon was being discussed in an honest and fearless way, but that issue — the magazine’s all-time biggest seller — was actually a response to the previous volume, in which a well-respected mechanech wrote that the overwhelming consensus of Orthodox mental health professionals is that struggling children are the product of dysfunctional families.

“Everyone was confused about this phenomenon, but although at the time my family was just at the beginning of this years-long journey, I knew that wasn’t the story,” says Rabbi Russell. “I knew that we weren’t a ‘dysfunctional’ family. But I also knew that if that was going to be the narrative, then all families with struggling kids would become desperate to micromanage them in a panic to get them to shape up, to prevent them from going out dressed the way they were, because they’d become a walking advertisement that ‘you’re a dysfunctional family.’

“The backlash was a terrible tragedy, parents fighting bitter and useless battles with their kids — I know because I was working with these families. It just fed into the underlying fear and panic and shame and embarrassment that all parents naturally have when kids don’t toe the line. It fueled the flames instead of being helpful.

“I knew it wasn’t true,” he says emphatically. “But I also knew one other thing: that if you have kids going off, and you’re willing to take the plunge, in relation to the normal functioning of a Torah family, you actually will have to allow your family a level of ‘dysfunction’ in order to save your child. It will most likely mean having someone in your house who isn’t dressed like the others and who isn’t keeping Shabbos.”

Around that time, there were two significant developments that bolstered Rabbi Russell’s learning curve. The first was that his daughter, after spending three years moving from one school to the next in search of the best place for her to grow, had reached the last stop. They were out of options.

“Tatty, the school I’m in isn’t for me,” she said in a phone call to Lakewood. “It’s not working. I think you know what I need. Maybe you can open a school for girls like me?”

So the Russells did. They opened a school called Tikvah, starting with their daughter and three friends.

Rabbi Russell empowered the girls with the responsibility of launching their own school. He wired his daughter $10,000 and told her to go rent an apartment, find a dorm counselor, and interview staff. They found the person they needed: Dr. Chana Stroe. Rabbi Russell hired her, and together they ran a unique institution, where bruised souls were able to find healing, and disillusioned young women were able to reclaim their neshamos. Within a year, his daughter was shomer Shabbos.

“We ran Tikvah for 10 years,” Rabbi Russell says. “I flew in frequently to supervise and support it and did all the fundraising. It was a ‘boutique’ school, between 10-15 girls a year, and we were very selective: In order to get in, you had to have stopped eating kosher and keeping Shabbos, be doing drugs and involved with boys — and come from a frum family. We took the girls no one else wanted.”

Tikvah closed when funds dried up in the wake of the 2008 stock market crash and subsequent recession, and reopened briefly after the Russells made aliyah, and Rabbi Russell established his clinical practice in Israel. It ran for another two years out of a villa in Ramot, with Yocheved Russell running the program with absolute belief in the girls’ potential to recover their lives and build their futures, but closed due to lack of funds right before Covid hit.

At the same time Tikvah was up and running, Rabbi Russell was tagged to lead Our Place, a teen drop-in center in Brooklyn, serving as its director for ten years.

During that time, his daughter found her way back and decided to get married and build a home on the foundation of Torah and mitzvos.

“She was about to go out to the kabbalas panim, when I got an urgent message that she wouldn’t go out until she speaks to me,” Rabbi Russell relates. “I rushed in, and she was standing there holding two tissues under her eyes as the mix of tears and makeup was running down. ‘Ta,’ she said, ‘I can’t go to the chuppah until you’re mochel me for what I did to you.’ I looked at her and said, ‘Sweetie, you don’t have to ask mechilah. You gave me more than you took from me.”

Not Bad, Just Sad

Between the young people at Tikvah, Our Place, Rabbi Russell’s clinical practice, and further research, it became clear that what was pushing a large swath of kids off the derech was unaddressed pain and trauma.

“I wasn’t seeing bad kids,” he says. “I was seeing good kids who’d been hurt. And we were learning that helping them to heal their hurt and pain, without mussar, punishments, or criticism, would free them up to make better choices.”

Mostly what he was seeing is what he calls complex trauma, which is the cumulative effect of a multitude of micro-traumas — and that can include constantly reliving the shame and pain of a singular event or experiencing a painful event every day (such as being bullied or constantly failing in school).

The three most common areas of trauma he pinpointed are physical and emotional violence or endangerment, inappropriate physical contact or age-inappropriate exposure, and failure to thrive in the school system.

The latter, Rabbi Russell claims, is as lethal as the other two. “In our educational system, every boy knows that if you want to give your parents nachas, you need to be a top learner — but a large number of kids also know that they’ll never get there. The underpinning of the system, as progressive as it has become, still exaggerates the chashivus of the few boys who have been gifted by Hashem with a great ability to learn, and too many of the other children grow up with a gnawing feeling eating at their insides that ‘I’m a loser.’ ”

He says it seems that about 20 percent of today’s students are phenomenal in learning and middos, 20 percent will not be fully observant by the time they graduate high school — and then there are the 60 percent in the middle.

“Those shteigers, the gifted 20 percent, will shteig anywhere. They always did and always will, with or in spite of the system. It’s mostly the 60 percent in the middle who are the ones I meet in my office all the time. And we’re seeing a new phenomenon, in Eretz Yisrael and Lakewood and Brooklyn and all over: They’re still frum, still keep Shabbos, don’t do tattoos, and aren’t angry or rebellious. But many among them have little or no real feeling for Yiddishkeit. There’s no passion, no sense of mission or purpose. These kids can sleep away the morning and put on tefillin sometime before shkiah. I call them ‘On the Derech/Uninspired.’ ”

And while these kids aren’t angry or rebellious, Rabbi Russell says they’re still in pain. “Because if you’re in a system where you’re choshuv if you’re a big learner, and you’re not choshuv if you aren’t, and everyone knows it about you, that can be traumatic. Do you know how many people I treat with learning trauma, who are still frum but can’t go near a Gemara, can’t go near a sefer?”

It makes for a depressing picture: Too many children graduate our educational system with low self-esteem, feeling like they were failures; then throw inappropriate exposure into the mix, and top it off with what Rabbi Russell calls the “Haskalah” of our generation — YouTube.

“A child who’s not happy with himself can easily get hold of a device and find his way to YouTube, where the entire world is open to him,” he says. “And it drags them away from Yiddishkeit. If their daily experience going to school leaves them feeling empty, and if they’re constantly exposed to the subtle message that they’re a loser, then the escape provided by YouTube and other online destinations is a needed relief.

“We talk about shemirah, about more and more filters, and think that’s the answer. I’m all in favor of shemriah and gedarim, but shemirah alone won’t work. I’m a witness that it doesn’t. It’s just not in tune with the kids of today.”

So what is the answer?

“We have to really talk to kids, to discuss these things age-appropriately. And we have to give them an authentic sense of purpose in life. Mesillas Yesharim tells us that the tachlis of this world is to do mitzvos, to serve Hashem, and laamod benisayon — withstand the tests that come our way. We adults know that this sense of purpose — having a long-term picture of what we’re meant to accomplish and taking small but significant steps to get there — is what gives us real joy and meaning. So why not teach it to our kids?”

Rabbi Russell tells of a yeshivish 15-year-old kid from a shtark family who came to see him because he was suffering from depression. “I sensed that something else was going on, something with him was not aligned. So I asked him straight out: ‘Are you looking at inappropriate sites?’ He admitted that he was, but begged me not to tell his father.

“I agreed and then said, ‘But I reserve the right to convince you to tell him. Is that okay with you?’ And he did in the end. But I was curious — how did he get in, when he has no device of his own and his parents’ computer is locked and filtered?

“ ‘Rabbi Russell,’ he said a bit condescendingly, ‘let me show you.’ In minutes he showed me how he was able to reboot my computer and bypass my passcode and filters.

“So of course, shemirah alone can’t stop them. We should have shemirah and gedarim, but we also need to have conversations with these kids — and they want the conversation, and they want the gedarim, I know because I talk to kids all day — but they don’t want to be yelled and screamed at. They want meaningful, attuned communication.”

Then, all too often, comes the guilt piece, the most complex and painful part of the picture: The parent realizes the child was abused or traumatized, and he wasn’t there to protect him. A parent sends a son to shul, and he falls into the clutches of a predator. A mother sends her daughter to school, and she’s bullied and traumatized, maybe even attacked. Or she sits day after day at her desk, absorbing the message that she just doesn’t measure up to expectations — a slow drip of toxicity that can corrode her sense of safety and emotional security, even though she hasn’t experienced any violence per se.

We send our children out into the world, daven for them, and yes, they can experience deep trauma and suffering. So when that child experiences this pain — say he was abused at 10, and at 15, all that pain comes out, and he stops keeping Shabbos, changes his wardrobe, and lies in bed all day — sometimes the hardest, most overwhelming part for parents is to face that their child has experienced trauma on their watch. Facing the possibility that your child was abused can be so overwhelming, it’s sometimes easier to pretend that it didn’t happen, or if it did, hope the child will somehow figure out a way of working it out.

It’s so painful and horrifying that many parents’ initial reaction is to close their eyes and say, “Can you please just get out of bed, put on a white shirt, and be a mensch?” — because they don’t think they have the capacity to touch that searingly painful place.

When a parent sees his child suffering and realizes that it’s coming from past or present trauma, how can he move forward? You can’t undo the trauma or the abuse, so what can you do?

That, says Rabbi Russell, is what healthy attachment is all about, and this is our avodah as parents. “We have a responsibility to our kids, and so we really need to strengthen ourselves in this area in order that we can be a safe harbor for our children. Yes, statistically, chances are high that some of our children will get hurt out there. So we have to make sure the home is a safe and secure environment where we tune into our children’s feelings and emotions. A place where they’ll be understood. And then hopefully they’ll be able to bounce back, even after a harmful experience, because they’ll have the resilience they need to survive and thrive.”

Shimon Russell’s original plan was to be a rebbi or mashgiach. He never imagined he’d become the worldwide go-to expert for kids-at-risk, and learn the sugya on his own family

Bonds of Resilience

When it comes down to it, what is the secret of raising a loving family? The answer, says Rabbi Russell, is creating healthy and loving bonds of attachment between child and parents, because when children feel deeply connected to their parents, when they feel “my parents know me, they’re tuned into me and actually recognize my uniqueness,” the bonds are cemented.

“Hashem created a world in which children are wired in their nefesh to want to give nachas to their parents, no matter how old they are,” says Rabbi Russell. “And when children feel unconditional love from their parents, then when appropriate rules and structure are imposed, they naturally absorb those rules and structure, because it becomes an extension of that love. They might not like it, but their nefesh craves it.

“Good attunement creates resilience to the outside world. Because deep down, children do want their parents’ world and the world of Torah. When we create a loving family, the modern-day ‘Haskalah’ will have much less pull, and even if they dabble in it, there’s somewhere to come back to and talk about it.

“And if he hasn’t yet come back? We want to repair the damage and restore the natural G-d-given desire of every child to please their parents. Deep down, all children want to make their parents proud — it’s how Hashem created all of us. So we want to get the child to a place of hope, where he can envision the possibility of making his parents proud again. But it will only work if we as parents, through unconditionally loving our children, can stir that imagination, that dimyon, inside our child’s heart that yes, they’ll actually want to sit at our Shabbos table one day with their own children.”

Your Picture

When Rabbi Russell and his wife were trying to keep their heads above water navigating the sea of OTD, Rabbi Russell says it was gehinnom oif di velt, until he was able to pass the hardest yet most crucial stage of all: to mourn the loss of the perfect picture he once had of the perfect family, to truly let it go.

Every parent has a picture of their ideal family, and parents of struggling kids have to bury it and mourn their loss in order to move forward. “That picture wasn’t meant to be yours,” he says. “But trust me, you’ll have a different picture, and it can also be special and wonderful, and it too can fill you, and you can have nachas and joy.

“But if you don’t let go of the original picture,” he cautions, “it’s going to get in the way, it will undermine you — because you’ll always be trying for the wrong picture. You have to go on the journey with the new picture, even if it’s not something you quite imagined. It has different subtleties, different twists than you thought, but you were created for that picture and not the other one.”

Rabbi Russell says it took a while, but he finally came to understand the famous Gemara in Niddah 16b that’s so frequently quoted yet often paid lip-service to. The Gemara says that there is a malach in charge of every fetus, determining whether he’ll be intelligent or limited, rich or poor. The Gemara continues with the famous quote, “Everything is in the hands of Heaven, except for fear of Heaven,” and Rashi explains: Every single aspect of our personalities and our journeys is determined by HaKadosh Baruch Hu.

“We all know how to quote this, yet we’re so busy blaming this neighbor and that rebbi and that friend for what happened to our children. I too was in that place at the beginning of the journey,” Rabbi Russell admits.

“When our kids are born, we all have these fantasies about what we think we got. A neshamah comes down for one reason, for its tikkun, and of course it would be very convenient if every baby would come into the world with a little tag tied to its toe announcing exactly what their particular tikkun is.

“It took me a while, but I came to realize that Hashem knows exactly what He’s doing, and that this child He gave me is my gift. This is meant for me. This challenge isn’t something that’s ‘in my way,’ it is my way. And I credit my children with waking me up to this reality. Because prior to this parshah, it was all just philosophy and academia.

“Today, when I say Hallel, when I give thanks, it’s a new level: Odcha ki anisani — I give thanks to You because You made me struggle. Vatehi li l’yeshuah — that struggle was my yeshuah, it freed me to be an authentic Jew. It was my salvation, and it came through the struggles. Even moasu habonim — the builders want to clear the lot to put down the foundation, and this huge rock is in the way. But then they realize — it’s not in the way, it is the way. I’m going to build right on that rock, right on that child who’s struggling. Zeh hayom asa Hashem — the day you realize Hashem did this for you, you can get up and sing. You don’t have to be miserable anymore. Because the problems are not in your way, they are your way.”

Rabbi Goldstein with one of his dozens of outreach titles. But the latest book was a learning curve all its own

Through the Rough Times

Rabbi Zalman Goldstein, the compiler of Rabbi Shimon Russell’s wisdom in book form, is founder of the Jewish Learning Group, publisher of The Complete Shabbat Table Companion, Going Kosher in 30 Days, The Kotel Siddur for tourists at the Western Wall, and nearly a dozen other outreach books used by Chabad houses around the world. He is also the man behind the Chabad Classics music series.

But after going through a painful and complicated divorce, he decided to branch out from kiruv publications and write the book Talking Divorce.

“There wasn’t much out there for frum people going through divorce, and about two years ago, I was far enough away from the pain of my own divorce that I was ready to write something meaningful and helpful for those contemplating or going through divorce themselves,” says Rabbi Goldstein, the youngest son of “Uncle Yossi” Goldstein a”h, composer of the iconic song “Hashem Is Here Hashem Is There” and master of children’s stories and radio programs.

The book includes a dose of reality — some people think they’re giving up something good for something better, only to end up with something worse; it’s about reevaluating what is really wrong with the marriage and whether divorce is the answer; and deals with how to proceed with a divorce without falling into legal or vindictive traps, destroying the kids in the middle, or taking revenge; and how to deal with issues such as conflicts in religious observance and parental alienation.

“It’s really like a support group inside a book,” says Goldstein.

But no book could take away the pain of the struggles he was facing with his own children, and that’s when he heard about Rabbi Shimon Russell and his work with struggling kids.

“Rabbi Russell’s videos and talks, and his openness about his own challenges, very much helped and guided me through my rough times,” he says.

Last year the two met in person at a Kesher Nafshi weekend, where Rabbi Russell has become a regular fixture, and Rabbi Goldstein had an idea: Over the years of writing and publishing, he had developed the skill for taking a river of information and distilling it onto the tip of a teaspoon for readers. Perhaps they could collaborate on a book, taking the wealth of Rabbi Russell’s teaching and consolidating it into an easy-to-read book for parents of all ages and stages?

It was a good shidduch, because people had been encouraging Rabbi Russell to write a book for years, but he simply had no time.

Rabbi Goldstein got to work, spending months assembling, sifting, consolidating, and shaping the material drawn from hours and hours of Rabbi Russell’s powerful presentations, some going back many decades. And the result is the new release, Raising a Loving Family.

For Rabbi Goldstein, this project was a learning curve all its own. “I learned new ways to support my children in whatever difficulties they were going through. It was extremely helpful because as some of my kids got a bit older and began choosing their own paths, I had to discover new ways to relate to them because of these new dynamics. Rabbi Russell’s material helped me navigate these muddled pathways and to grow internally to be a loving father above and beyond where I was before. So for me it’s been a bridge to help me get to a better place in the face of unexpected curve-balls.

“I often think, why do my children have to go through all this pain? Writing this book and working to internalize its powerful messages helped me to reframe and remember that we didn’t put them in this life, but Hashem put them in this life. It taught me that raising our children is not only about who they become, but also about who we become in the process. That realization was monumental in shifting the focus and direction of my energies, and opened a new window of light in my life as a person and father. It was important to me to make this vital information and chizuk available for other families too, and not just those who are struggling. If it was helpful to me, I want to share it with others too.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 939)

Oops! We could not locate your form.