Grab It While You Can

The will to change, to grow, must be verbalized

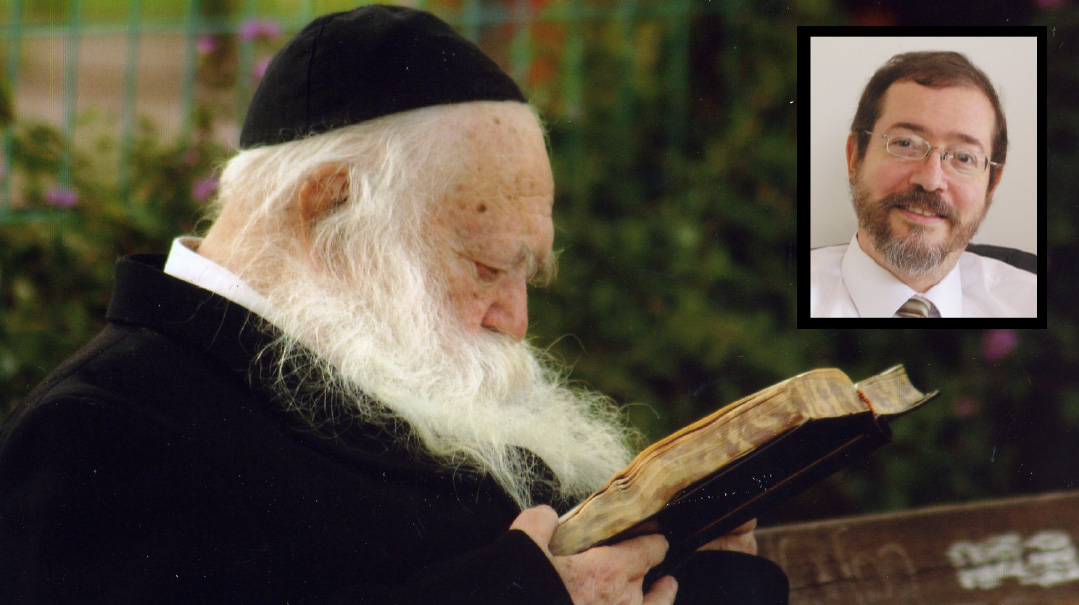

The words of Rav Yonoson Eibschutz in Yaaros D’vash (2:7) about the spiritual effect of an adam gadol leaving the world are quite startling in their implications for the rest of us left behind. The towering 18th-century gadol writes, “With his passing, all of his deeds, attributes, and acquisition of shleimus are rendered hefker, ownerless, and every Jew can take possession: This one can say, ‘I’ll take possession of his anavah,’ and this one can say, ‘I’ll take possession of his hasmadah in Torah,’ and this one can say, ‘I’ll be a pursuer of peace like him,’ and this one can say, ‘I’ll be compassionate to the downtrodden, a father of yesomim and almanos like he was,’ and this one can say, ‘I’ll be punctilious in performing mitzvos like him,’ and this one in being a fearer of sin like him. And everyone can take possession of one attribute.”

The hopefulness inherent in those words is obvious. It means that a time like now, as we reel from the loss of Maran Rav Chaim, is a window of great spiritual opportunity. It’s reminiscent, l’havdil, of those contests years ago in which the winner, having answered some riddle, was granted ten minutes alone in a bank vault. Armed only with a burlap sack, it was a chance for him to stuff into it as many five and ten dollar bills as he was physically able, as the seconds ticked down to zero.

But Rabbeinu Yonoson’s words, if read carefully, also seem to convey a daunting message. “This one can say… and this one can say… and this one can say.” It’s not sufficient to simply decide in one’s mind to adopt something precious from that of the great niftar. The will to change, to grow, must be verbalized. Only with a statement of the words — audibly enough for him, and perhaps others, too, to hear — can he concretize and render permanent what might otherwise remain a faint, and ultimately fleeting, inner desire.

Indeed, Rav Moshe Sternbuch cited the Yaaros D’vash in his hesped for Rav Chaim, and encouraged each person listening “to announce to his family his decision to devote more time to Torah, or that he has decided to daven with greater kavanah, and with this he’ll be zocheh to the ma’alah of teshuvah, for it to be reckoned as if he were born this day into a new world.”

The Yaaros D’vash doesn’t tell us how long this period of hefker lasts, but presumably there’s a specific window of opportunity. Perhaps we can hope that it extends at least through the 30 days in which hespedim continue to be made. At some point, however, the seconds remaining in this greatest of all bank vaults will tick down to zero, too.

That same idea — that there are times when there’s a special siyata d’Shmaya available but if one doesn’t seize upon it, it will go away— is something Rav Chaim himself once conveyed to his very first talmid, Rav Tzvi Rotberg. Reb Tzvi, today the revered rosh yeshivah of Yeshivas Beis Meir in Bnei Brak, is a much-younger first cousin, once removed, of Rav Chaim (his grandfather, Rav Meir Karelitz, was a brother of the Chazon Ish and brother-in-law of the Steipler Gaon), and at age 12, he began a daily learning seder with Rav Chaim which lasted nearly 17 years.

In all those many years, there was only one day on which he and Rav Chaim didn’t learn together at all: the day of his wedding. The day before, when they finished their seder, Rav Chaim said to him, smiling, “What about tomorrow?A kvi’us is a kvi’us…” Reb Tzvi asked his kallah’s permission and went to the same neitz minyan he and Reb Chaim always attended, expecting to have his seder with Rav Chaim following davening. But when he walked into shul, Rav Chaim looked at him in wonderment, and following davening, he said to Reb Tzvi firmly, “Today, we’re not learning,” and insisted on accompanying the chassan home.

Rav Chaim once told Reb Tzvi the following story about “an avreich” he knew — which Reb Tzvi understood was Rav Chaim himself — who took a brief nap each afternoon. He didn’t want to sleep more than a half-hour, but he also didn’t have an alarm clock. Each day, after 30 minutes had elapsed, a fly would arrive — like clockwork — and begin buzzing near his ear, waking him.

One day, however, the avreich was particularly tired and decided to continue napping for several minutes after the fly arrived. And from that day on, said Rav Chaim, the fly never again appeared. The lesson, Reb Tzvi concluded, is to take advantage of the Divine assistance that’s proffered before it flies away — sometimes literally.

In his hesped for Rav Chaim, Rav Sternbuch also cited the Gemara (Moed Katan 25b) which states that when Rabi Yochanan was niftar, he was eulogized with the words, “This day is as difficult for Klal Yisrael as the day on which the sun sets at midday.” He explained that although Rabi Yochanan lived to an extremely old age, he continued to illuminate the skies of Klal Yisrael until his last day, every bit as much as he had earlier in life. His passing was analogous, then, not to a gradual sunset so much as to its sudden, shocking disappearance at midday.

As the unfortunate events of the few days since Maran Rav Chaim left us seem to demonstrate, the full strength of his brilliant rays of Torah and tzidkus were protecting us far more than we understood, until the very last moment of his time here. May the Ribbono shel Olam only spare us any further agony, and as Chodesh Nissan, the month of redemption, arrives, bring the Redeemer speedily.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 906. Eytan Kobre may be contacted directly at kobre@mishpacha.com)

Oops! We could not locate your form.