Gone Missing

We can only begin to decipher the disturbing scenes of Wednesday’s lethal raid on the Capitol by asking the right questions: What allowed these events to morph from the unthinkable to reality?

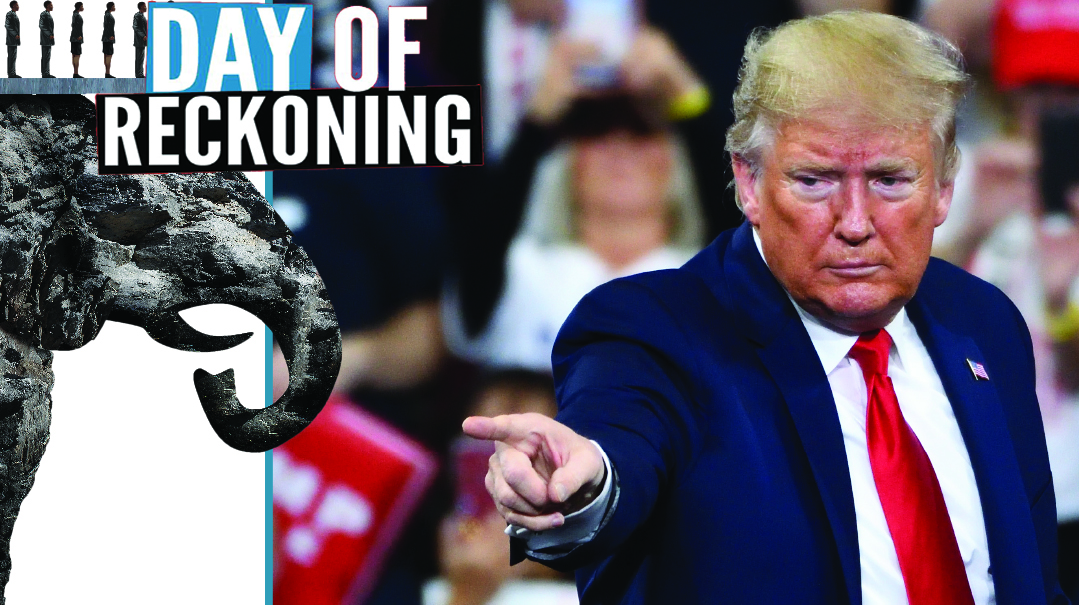

Photos: AP Images

On Wednesday January 6, crowds of Trump supporters — fully convinced that the election had been stolen and urged to take it back for their president — stormed the nation’s Capitol, bringing bloodshed, mayhem, and shock.

Where does the GOP go from here? With the Trump era at a sudden and shattering end, how can the party find new leadership and continued relevance?

What’s waiting in Washington for America’s Orthodox Jewish community, where many are approaching the next four years with trepidation?

And what messages do those disturbing images of extremism and violence hold for us as observant Jews?

Mishpacha magazine, though very well received in the Jewish Torah community, has no significant readership outside of our community and among “the powers that be.” So why write in Mishpacha magazine about the shocking events that happened last week at the United States Capitol?

The Gemara says that someone who sees a sotah in her disgrace must take on abstinence from some aspect of this world’s physicality. This is perplexing. He did not see the sotah at her revelry, where he might be tempted to imitate her. Rather he saw her at her most painful moment — shamed and about to be killed. Why then, would he need to add more precautions?

The answer is twofold. Firstly, there are behaviors that are simply unthinkable to us. We do not only refrain from killing someone because of the severity of the issur. We refrain because it is unthinkable. Once a barrier to an action, however severe, has been broken, it has then become “thinkable.” In the case of a sotah, seeing clear proof that a woman has transgressed this prime sin means one of the greatest barriers has been breached.

The second reason is mystical in nature and is quoted in chassidishe seforim. There are reasons why Hashem sends events our way. This is true as Hashgachah pratis on the individual level and, even more so, as Hashgachah klalis on the tzibbur level. And so if Hashgachah had us witness a “sotah b’kilkulah,” then it is to point out what we need to fix.

In a sense, both of these reasons can be aptly expressed with the Yiddish maxim “vi es kristeled zich, azoi yiddished zich” [lit. as Christians act, so do Jews]. In other words, the behavior of the Jewish community tends to follow the general zeitgeist.

This article, therefore, is not intended to help America right its ship. Rather it is intended to jumpstart introspection in our community and to suggest a possible message that HaKadosh Baruch Hu is sending us — to see what we need to be wary of so that we don’t subconsciously (or worse, consciously) flow along with the spirit of the current events.

To be clear, much of this could be equally applied to the shocking and dangerous mob violence associated with numerous BLM and Antifa protests across the country. But the affiliation of many in our community — for hakaras hatov or for broader reasons — with the Trump movement (and, for the most part, not with BLM or Antifa) makes the timing of this essay more appropriate within the context of Wednesday’s events.

Asking ourselves “what caused people to act the way they did” is approaching this from the wrong direction. The events that happened should have been unthinkable. Rather we need to ask, “What was missing that allowed these events to be thinkable, to be possible?”

I think the two key missing factors that allowed this to happen are the same factors necessary for any mob action: 1) a lack of daas, and 2) not regarding civility as a virtue.

We saw the lack of daas in the way the events unfolded. They followed the typical script of a populist revolt: simple slogans, unencumbered by nuance and unburdened by proof. “Stop the Steal,” “The Deep State,” “Rigged Election.” These are serious accusations. In order to prove them, one needs a calm, deliberate forum to consider evidence and to weigh it. The courts of law repeatedly ruled that no material evidence was even offered by those questioning the election. But rousing slogans were fired at machine-gun pace. Calm and cerebral deliberation seemed to be the furthest thing from people’s minds (insofar as they had any).

I make these comparisons understanding that there are important distinctions between the events of Wednesday and the ones I’m about to mention. But if you have seen clips of extremist leaders rousing the masses (against the Jews) or inveighing against the bourgeoisie (usually code language for the Jews) — the dynamic is eerily familiar. People relish the simplicity of the message, the adrenaline rush, the ready solution to their woes — and a roar of thunderous satisfaction greets the speaker. This lack of employment of rational process and daas is but one half of the necessary ingredients.

The other factor is not regarding civility as a virtue.

If people don’t see menschlichkeit (civility) as a virtue, then what is to stop them, when they become distraught or frustrated, from behaving the way that mob did? We tend to have mental images of what is “doable” or “praiseworthy” action. If animal behavior is constantly pictured as “fun” or “heroic,” then given the chance, wouldn’t that be our default behavior? If patience and civility are the hallmark of a “loser,” who would want to be a loser?

Perhaps the Torah’s most powerful description of mob behavior is that surrounding the Egel Hazahav, the Golden Calf. When Yehoshua hears the revelry, he is unsure as to what he hears. Moshe responds, “it is not the sounds of victory; nor is it a cry of the weak. Rather it is the sound of mocking denigration, intended to hurt and cause anguish” [as per Rashi]. The sounds of a roaring mob are not an expression of self; rather they are a destructive cacophony.

And now particularly with regard to our own Torah community. Do we truly have daas? Do we find ourselves and our children thinking issues through? Weighing the different sides deliberately, and making nuanced decisions?

Unfortunately, too often this is not the case. We expect our speakers and media to be solidly on one side or the other, avoiding complexity and anything less than a claimed-to-be perfect solution. My father-in-law, Hagaon Rav Binyomin Beinush Finkel ztz”l, would often counter an excited claim by a young person with the question, “So how do you know?” (He did this even though he might have been in agreement with the person’s position.) If they responded with “Well, everyone knows,” my shver would calmly continue, “And how do they know?” This was one of many ways he inculcated within his children and talmidim a sense that we must apply yardsticks of objectivity to the best of our abilities. So much for daas.

But worse still, do we genuinely see civility as a virtue?

The Rambam in peirush haMishnayos (Kiddushin 4) defines derech eretz as a “decent society of people, with civility (nachas) and mussar.”

A society where dignified and calm interaction is fostered is a good society to live in.

Yes, when it comes to people we agree with, we are affable. But if we disagree even in the slightest, the other side can become the object of every vile attack, from anonymous pashkevilim to harassing phone calls, to calling a choshuve rav by a nickname — all is fair game.

This destructive behavior does not end with the “outside” enemy. It is a mode of behavior and as soon as a member of “my” group dissents, he in turn is given the same treatment. And society keeps fracturing helplessly.

There is nothing wrong with disagreeing, and even splintering into a new group if your differences are material enough. But if we cannot muster civil and menschlich behavior toward intellectual and ideological opponents, then our society will become most unpleasant for all.

Many years ago, I had a discussion with a rather thoughtful and intelligent Yerushalmi. He posited that the fact that Yerushalayim is today a city of Torah and did not go the way of other cities in Eretz Yisrael, is probably due to the effect of a certain group of extreme kano’im.

I responded by asking him to look at this same group of kano’im 50 years after they made a stand for their holy city. Many of them have spent all of their lives and children’s lives fighting. First they fought Tziyonim; then they found more and more things to fight about, and splintered into more and more mutually opposed factions. The kana’us never built anything constructive, and so it can never become part of the foundation of a stable society — because derech eretz is not part of its hashkafah.

My rebbi, Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz ztz”l, spoke sharply against kana’us. But that needs to be accurately described. He did not speak against any shitah per se, pro or con this opinion or another. And there were a fair amount of weighty talmidei chachamim in the Mir yeshivah who had anti-Zionist shitos; but they carried themselves with dignity, and their words were measured and thoughtful. Their interactions with others with whom they strongly disagreed were cordial and polite. These gedolei Torah were respected greatly by Reb Chaim and the rest of the Mir because they were part of a society of “derech eretz and mussar.”

Reb Chaim spoke only against people (yes, on occasion even “talmidei chachamim”) who were hotheaded, incapable of listening to another side honestly and weighing the arguments. He spoke against people whose favored mode of operation was mob-like: rowdy demonstrations and garbage burning. Reb Chaim did not tolerate those who used tactics that terrorized their opponents, from name-calling, to anonymous, crass pashkevilim, to harassment.

We need to ask ourselves: Are our children being taught to apply yardsticks of objectivity when considering opposing views? Are they being taught derech eretz and to see civility as a virtue? Are they taught to deliberate issues instead of grabbing on to an adrenaline-pumping slogan?

Yes, it’s true that young people gravitate to those emotional extremes, but it is our job as parents and rebbeim and adults to see to it that our children have adult role models, so that when the time comes, they can mature and settle down appropriately.

When batei medrash had a smaller ratio of talmidim to rebbeim, one could personally witness the day-to-day interactions (including in inyana d’alma) of great people, and talmidim would pick up this vital aspect of life. Gadol shimusho yoser me’limudo. At the Mir, and other yeshivos, we personally watched gedolei olam. We watched their deliberation and felt the weightiness of their decisions. We saw the respect they showed toward others, even if they disagreed with them. Today, with giant impersonal yeshivos, do talmidim get to see these interactions from close range?

(It used to be that even the secular studies departments at our yeshivos would play a role in this aspect of personal development. A teacher of younger grades would teach “good manners” and those who taught higher grades would teach about multisided issues.)

If parents make an effort during family discussions around the table to force their children to speak calmly and civilly, asking them to explain the basis for their claims and prodding them to find any possible “weakness” in their points, those children may someday develop that level of calm thoughtfulness.

Another element that has begun to plague our community — and which especially manifested itself during these last elections — is our emotional involvement with the political candidates and their parties.

No candidate or party represents Torah values. Neither the Republican nor the Democratic platform is Torah. (And this is beside the fact that their political “ideologies” are shifting sand.) A Torah Yid has no business identifying with either party.

Klal Yisrael has many needs and sensitivities. We weigh the different options and vote for a candidate or party based on what is important to us. We engage in political barter: a vote from the community in return for advancing values important to us and allocating vital resources. We are courteous and respectful to all, but we do not identify emotionally with any candidate or party. In fact, emotional enthusiasm for a candidate or a party is an “aish zarah”!

Furthermore, the events last week at the Capitol Building should bring home a truth that we keep failing to internalize. In strenuous situations, all political movements of the right or the left will, at some point, be turned against the Jew by their fringe elements. The Nazi paraphernalia evident at Wednesday’s riot and some of the comments made should remind us that there are no natural lovers of the Jewish People. Antifa and QAnon share a common antipathy toward us. Communists and Nazis, many Christians and Muslims, many of the landed conservative gentry and the liberal elites — all dislike us. Baruch Hashem, we can and should get along civilly, but why would we become enthusiastic cheerleaders of any candidate?

Recently, Rabbi Yonoson Rosenblum wrote an article in these pages explaining why he felt President Trump has made mistakes. In response, Rabbi Rosenblum did not get letters carefully explaining possible errors in his thought process. He got seething, emotional hate mail.

What is that all about? Why is a Yid emotionally invested in an American president, party or personality notwithstanding? Hakaros hatov is certainly appropriate, as are strong arguments why or why not he may be the best candidate for Klal Yisrael. But is a president of the US a personage that merits adoration and adulation, similar to an adam gadol?

This is perhaps the great lesson for us. It is important that we successfully navigate the world of American politics. There are many issues that can help or hinder our continued success. But it is an environment alien to a Torah Yid, and never do our emotions or neshamos belong in that world.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 844)

Oops! We could not locate your form.