From Kovno to Coca-Cola

We do know is that this story is a Coca-Cola classic. And it’s kosher for Pesach, too!

A leading rabbinic figure in early 20th century America was Rabbi Tuvia (Tobias) Geffen of Atlanta, Georgia. The sandek at his bris in 1870 was Rav Yitzchok Elchanan Spektor. A musmach of the Slabodka yeshivah and the Kovno kollel, young Tuvia possessed a legendary hasmadah. Family lore has it that when Tsar Nicholas II visited Kovno and the entire city gathered on the streets to view the spectacle, Tuvia sat alone in the beis medrash, completely engrossed in his learning.

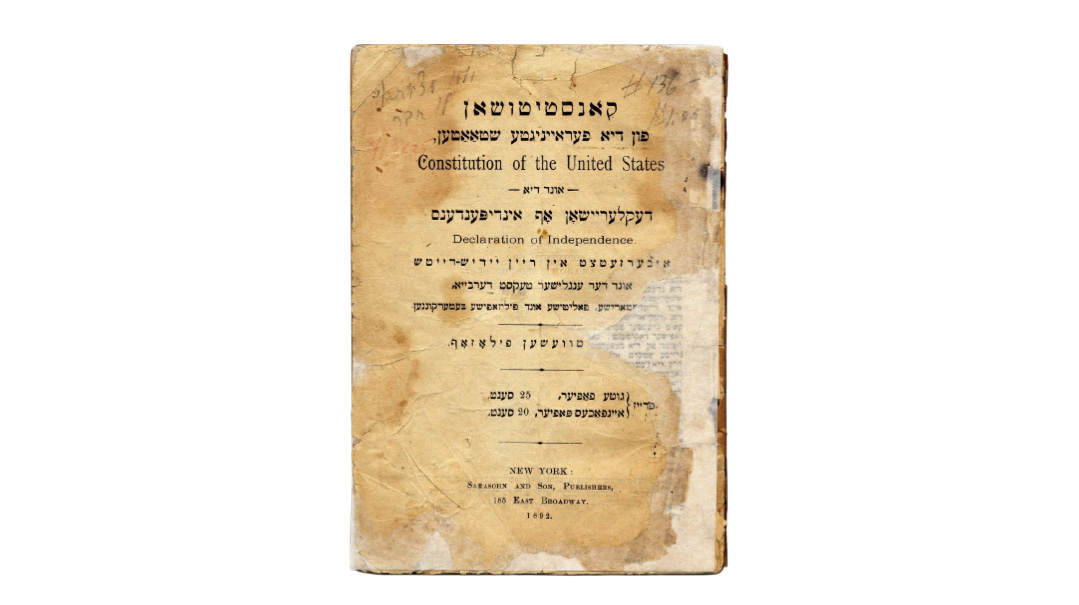

As violent anti-Semitism reared its ugly head at the turn of the century, Rabbi Geffen and his family joined the mass immigration to the United States. He commenced his rabbinic career on the Lower East Side before moving to Canton, Ohio. He eventually took a position in Atlanta in 1910, where he would spend the next six decades shepherding the burgeoning community, as well as influencing the greater Southeast.

Along with his wife Sara Hene, he built a home that was legendary for its warmth and chesed. From Rav Elchonon Wasserman to newly minted Jewish GIs stationed at a local base, few passed through Atlanta without stopping at the Geffen home. The Geffen children recalled that during World War I, their home was so crowded with soldiers for the Pesach Seder, there were no seats for them at the table.

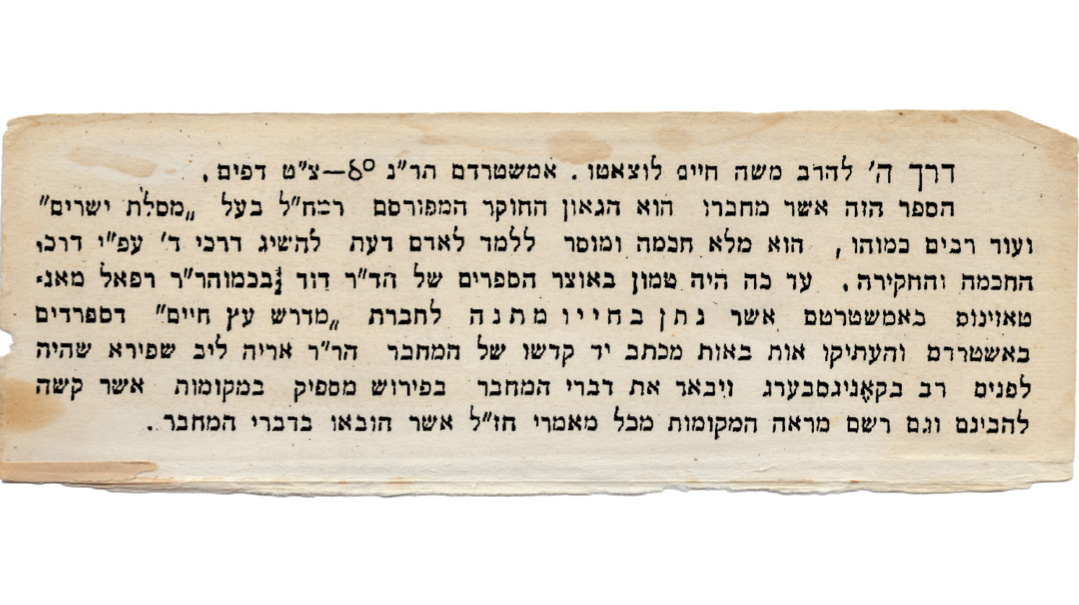

A legendary baal darshan and the author of five seforim, Rav Geffen did not see himself above sitting alongside his mispallelim on a regular bench in shul. He encouraged his community to go above and beyond in tzedakah activities, raising large amounts of funds for relief efforts in Europe. He also served as an emissary of the Slabodka yeshivah, making regular trips to neighboring states like Alabama and Tennessee to raise funds for his alma mater.

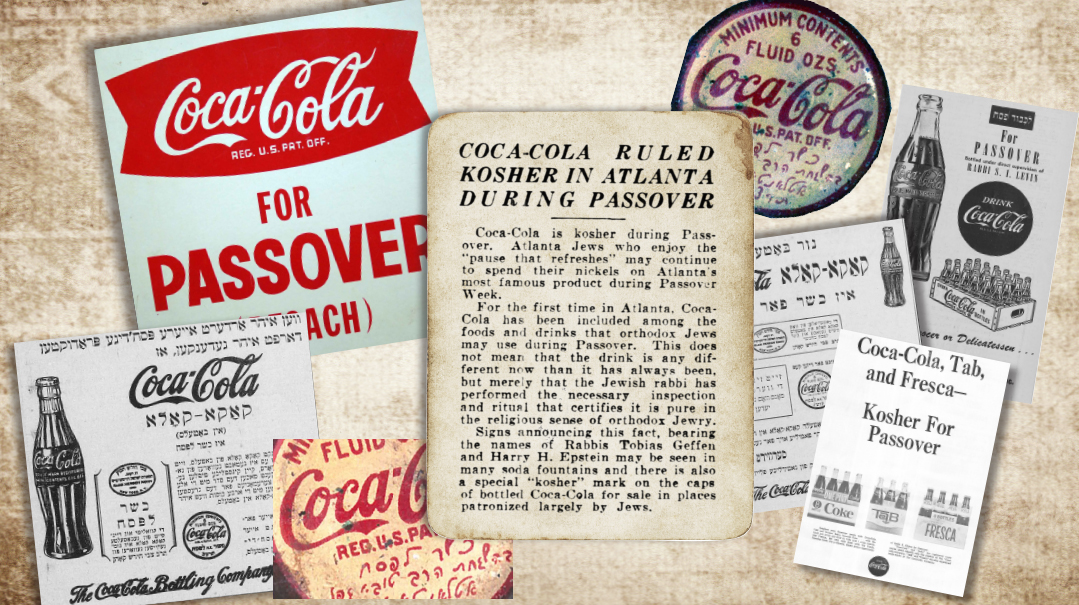

In 1935, he was tasked by the Agudath Harabonim with determining whether Atlanta-based Coca-Cola was fit for consumption by the kosher consumer, and he quickly discovered that it was not. There seemed to be two distinct issues — the soft drink contained glycerin, which would make it nonkosher all year round, and the sweetener used presented a problem on Pesach.

It turned out that the Coca-Cola company’s general counsel was a nonobservant but passionate Jew named Harold Hirsch. He spent decades successfully battling imitators of the brand that was quickly becoming America’s favorite refreshment. He even had a hand in designing the company’s iconic glass bottle. As a proud member of the Atlanta Jewish community, Hirsch was involved in various philanthropic endeavors and maintained a warm relationship with Rabbi Geffen. In that capacity he was able to intervene on the rabbi’s behalf and gain him access to company executives to discuss the kashrus matter.

The end result was a landmark teshuvah that ultimately solved the kashrus concern, and ingredients were substituted that rendered Coca-Cola kosher. That same year Rabbi Geffen was successful at making the soft drink kosher for Pesach as well.

In exchange for access to the vaunted secret formula, Rabbi Geffen was sworn to confidence. The teshuvah he wrote in his sefer Karnei Hahod on the subject is filled with codified references to various ingredients, in order to conceal the actual formula, which remains classified to this very day.

What remains is the question: Why was Coca-Cola motivated to make their product kosher, even kosher l’Pesach? We can safely assume that it wasn’t the small kosher consumer market in 1935 that spurred them to action. Was it the obsessive Coca-Cola drive to market the drink everywhere in the world? Perhaps. In November 1989, company representatives handed out free bottles of Coke to East Germans at the fall of the Berlin Wall, helping cement the drink’s status as a symbol of freedom to those behind the Iron Curtain.

Or maybe it was due to the regal-looking Rabbi Geffen, who commanded such respect from Southerners? We’ll never know. But what we do know is that this story is a Coca-Cola classic. And it’s kosher for Pesach, too!

Telshe Royalty

Born into a family that stressed diligent Torah study above all, Rabbi Geffen’s pious sister Osnas married the great Rav Chaim Rabinowitz, known as Rav Chaim Telzer. Following the Geffens’ move to the United States, they would help support the great gaon and his family. In the introduction to his sefer Nezer Yosef, Rav Geffen memorialized his sister and her son Rav Azriel (Rav Chaim’s successor as rosh yeshivah in Telshe) who were murdered in the Holocaust Hy”d.

The Rabbi and the Rough Rider

In 1904, the Geffens welcomed a new son, whom they named Aryeh Leib. The bris occurred on November 8, the same day Teddy Roosevelt was elected president. The rebbetzin later recalled everyone hastily running off from the bris to vote, a privilege they did not enjoy back in Europe.

In 1907 when living in Canton, Rabbi Geffen was invited to the dedication ceremony of the William McKinley Memorial — which fell out on Simchas Torah. When he discovered that several of his congregants were planning to attend, he announced he would join them in walking the several miles to the event. Rav Geffen would later recall the dramatic arrival of President Teddy Roosevelt decked out in full Rough Riders regalia, riding his favorite stallion to the ceremony.

The Prince of Egypt

During his early years in Atlanta, Rav Geffen was contacted by the Ashkenazic chief rabbi of Cairo, Rav Aharon Mendel Cohen. Rav Cohen knew of Rabbi Geffen from reading his various entries in Torah journals, and was also aware of how much Rabbi Geffen had helped communities in Eastern Europe. The growing Ashkenazic community in Cairo was suffering greatly and needed financial assistance. Rabbi Geffen quickly responded, establishing a vital link between the Atlanta and Cairo communities that lasted for many years.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 853)

Oops! We could not locate your form.