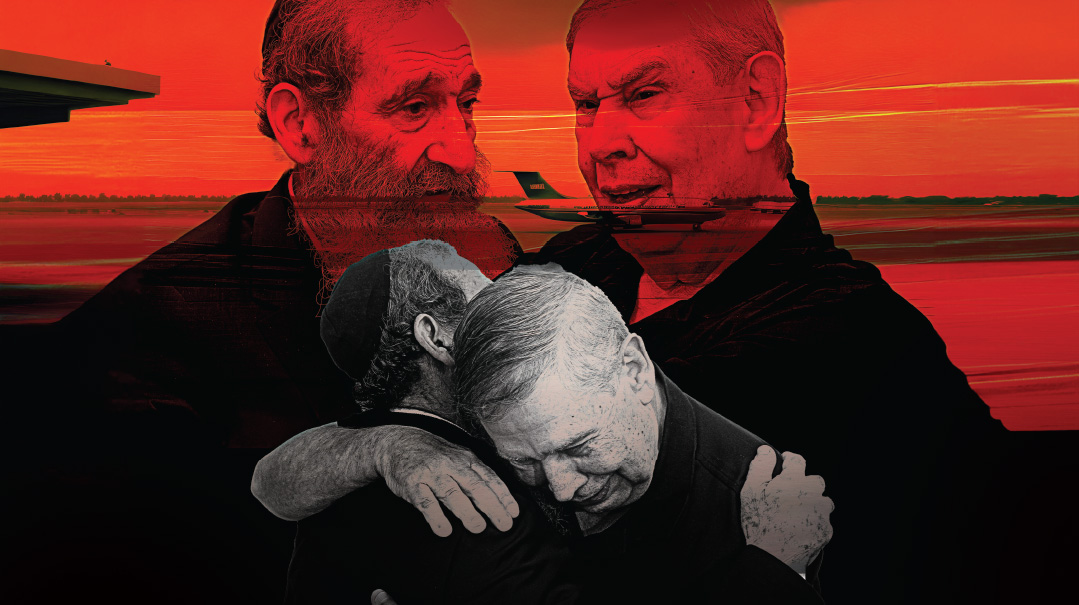

From Benny, With Love

Benzion Fishoff’s secrets for healing rifts and nurturing peace

Photos: Meir Haltovsky, Fishoff Family, Mishpacha archives

I first met Mr. Benny Fishoff when he wanted to compile a manuscript for the benefit of his grandchildren: about how a 16-year-old bochur says goodbye to his family, never to see them again, yet helps rebuild a shattered people. But every night when he closed his eyes to fall asleep, he would see the faces of his loved ones, hoping he was doing their memories justice. With the release of B’Ahavah, Benny, you can be the judge

In Shamayim, every person has a book — the record of his accomplishments, his challenges, his good days, and harder days.

In This World, it’s a bit trickier: Who gets to have a book? How does it work?

It’s a good question, and, as promising an opening as that was, I don’t have a clear formula with which to answer it. I can only tell you about this book, about what it was like to sit with Mr. Benny Fishoff a”h — and not just for me, but for most of the people who had the privilege — and the attempt to get the experience down on paper.

Over the last few years — during the time I forged a personal connection and then, in the past two years since his petirah — I’ve often pondered what it was about him. Charisma is the poorest, hollowest word to describe it. Graciousness is a bit better, and generosity of spirit even closer.

But it was more. Here was an older Poilishe gentleman, with the gentle humor and honesty and pikchus unique to that sort of Jew, and the term that kept popping up in my mind was “baal mussar.”

He was an unlikely candidate for the title, for sure. He wore elegant suits, enjoyed good restaurants, and good jokes. So how could he be a baal mussar, with the associated severity and ascetism?

Because he was. He just was.

He was a master of self-control, seemingly immune to anger, conceit, pettiness, or bitterness. He rejoiced in other people — he radiated dignity, and he could convey it by simply saying hello. His greeting came along with the flash of warmth in his eyes, the smile that told you that you mattered, the way he could listen to someone a quarter of his age with genuine interest.

When he spoke, it was not only wise, it was also kind — not an empty, trite compliment, but words that restored something inside of you. (Later, I would learn about the copies of Mesilas Yesharim at his bedside, on his office desk, and with which he traveled, but that’s not the type of mussar I mean, in any case.)

I had always known the name “Benny Fishoff,” sort of a legendary askan before we started to manufacture legendary askanim. The generation that had lost it all and that had been forced to start again didn’t have the luxury of also rebuilding the wider community, but he found a way to do that, too.

Yechiel Benzion Fishoff was born in 1922 and raised in Lodz in a kehillah saturated with the spirit of its many Gerrer shtiblach. As a teenager, he received a surprising brachah from the Imrei Emes of Gur that carried him and shaped him — “Ivdi es Hashem b’simchah. Der Eibeshter zohl helfn zolst bleibn a Yid (Serve Hashem in joy. The Eibeshter should help that you remain a Jew). Halevai, halevai …” — the words accompanying him as he escaped Poland for Russia. Armed only with courage and wits, he made his way through various daunting challenges, arriving in Vilna and joining with the bochurim of Yeshivah Chachmei Lublin. Together with hundreds of others, he escaped Europe on one of the coveted visas issued by Japanese consul Chiune Sugihara, surviving the war years in Shanghai, where he also learned some English and the basics of foreign exchange — but mostly, lessons about being kind to strangers that would stay with him forever.

He came to America completely alone, having lost his entire family. Determined to build a new family, he immersed himself in business, so that he would have a means of providing for them.

In 1949, he married his wife, Marilyn (Nieder), and together, they built a strong, loving home.

The following years, on his first visit to Eretz Yisrael, Reb Benzion met the new Gerrer Rebbe, the Beis Yisrael, who pulled him back “home” with a single pithy remark, and from that moment on, Mr. Fishoff would belong to Ger, a devoted chassid of its rebbes, a proud supporter of its mosdos, and a Yid who derived his spiritual energy from the words of the Sfas Emes.

Though business success had made him a baal tzedakah, he gave so much more than that, and the organizations and causes that affiliated themselves with Benny Fishoff were many. Within Agudath Israel, he was looked at as a statesman, but there was virtually no major Orthodox cause that did not consider him their own.

I reached out to Benny Fishoff randomly for a book I was working on, having gotten his email address. He was about 90 years old at the time, and I didn’t imagine that he really ever saw those emails.

He answered me about 30 seconds later, inviting me to come talk to him, so I did.

On a summer night in 2012, I went to Forest Hills, Queens, with a list of questions. I don’t think I got to them that night, or even the next time we met.

He was certainly an interesting conversationalist, this banking executive who had been a child in Ger of old and a bochur during the years of salvation with the Mir in Shanghai, but that’s not why I was enamored of him.

It came down to his middos: how he spoke to his wife, how he answered the phone, how in the stories he told, the heroes were always other people.

He mentioned that he, too, was looking for a writer because he felt compelled to record his life-story for the benefit of his grandchildren. He wanted them to know who their great-grandparents were, where they came from, but — and this is so classically Mr. Fishoff — he did not want his relationship with them to be that of an “old zeidy telling them the same sad stories again and again.”

He did want the story down, however. He had left home as a boy of 16 and never again saw his parents or grandparents, his siblings, friends, or neighbors.

He once told me that every night, when he closed his eyes to fall asleep, their faces would come to him, one by one, and he would wonder if he was living a full enough life to represent them all. He hoped that he was.

I was honored to accept the job, and started to sit with him regularly. It started out as the story of a survivor, but along the way, it went off in different directions — an original, fresh, fascinating narrative rich in detail, humor, insight, and practical advice.

At one point he told me that he wanted to add another section: not family history, but business. He didn’t want his grandchildren to hear his ideas about how to make money, he wanted them to hear his opinion about how to lose money.

“I want them to learn how to move on when things don’t go your way, to know that for every deal that works out, there are many others that don’t. I want them to know that failure isn’t the opposite of success, but part of the process.”

He would speak, I would write, and he would review. He would muse as he did so, and those musings themselves were so rich in seichel and perceptiveness, so relevant and helpful, that I would start writing again.

Finally, in 2016, the manuscript was ready for his grandchildren. One of his friends took a peek at it, and then another friend followed. A third noticed it lying around and suddenly, there were requests to borrow it.

The manuscript was unique, they said, in that well beyond history, it was a handbook on relationships and on the gift of the family. It was a manual on living peacefully and sacrificing for peace, and most of all, on emunah and simchas hachaim.

But Mr. Fishoff was torn, too humble to believe his story was worth reading for anyone besides his own family, too giving to refuse the requests of others. He decided to ask Rabbi Meir Zlotowitz, whom he trusted implicitly.

The founder and president of ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications said he would read the manuscript and think about it.

At the time, Rabbi Zlotowitz made a comment to me that I thought was just cute. “When I grow up,” he said, “I want to be like Benny Fishoff.”

It wasn’t just a quip, I would learn. It turned out that most people in Mr. Fishoff’s orbit were subconsciously trying to emulate him, to figure out what he would do in a situation and then do the same thing, to be viewed by others the way that they viewed Mr. Fishoff.

Within a few months of that conversation, Mr. Fishoff was ill and could no longer communicate, and Rabbi Zlotowitz was niftar. The manuscript sat around until two years ago, when Mr. Fishoff was niftar.

In the weeks following his passing, there was a flood of memories and reflections, tributes from the rabbanim, entrepreneurs, and great organizational leaders with whom he worked hand in hand, but also from the doorman, the waiter, and the parking lot attendant, who considered him a close friend.

We took the old manuscript and added a few chapters — not his memoir, but his essence. Not his take on the world, but the world’s take on him.

Together, the two parts fit so perfectly, the very values he praised in others becoming the defining characteristics others saw in him.

The title is taken from the way he would often sign off his emails and text messages: “B’ahavah, Benny.”

The word “ahavah” carries so much of what he represented, a love of life, a love of other Yidden, and most of all, a love for the Creator, whose goodness had so humbled him.

And maybe that’s the answer as to how conversations become manuscripts and manuscripts become books.

In Heaven, they decide.

One of the unique areas of Mr. Fishoff’s public service was the role he played in arbitrating and mediating, trying to bring peace to sparring business partners, organizational heads, or family members.

Unfortunately, he was very experienced in this area, always being called in to help. And he did so, by mixing his keen business sense, his inherent respect for people and his natural intelligence to help come up with a solution that could please both sides.

In the following excerpted chapter from the upcoming book, he shared some lessons that he thought could help others. At a time when each and every one of us is so desperate for added brachah in our lives, when we are so eager to merit the Divine protection that will spare and save us and our entire nation, investing a bit more shalom seems so right.

At Mr. Fishoff’s levayah, his son Avi commented that Rabbi Moshe Sherer would refer to his father as a “malach hashalom,” an angel of peace. Avi then looked at the aron and quietly said, “Tzeischem leshalom malach hashalom, go in peace, angel of peace.”

Go in peace, knowing how much peace you have left behind you, Mr. Fishoff, how your memory inspires us still.

In Pursuit of Peace

Benny Fishoff’s efforts to nurture shalom — in his own words

The following is an excerpt from the new release B’AHAVAH, BENNY: Reb Yechiel Benzion Fishoff, a Story of Dignity, Generosity, Wisdom and Warmth (ArtScroll/Mesorah),

by Yisroel Besser

A TIME TO LISTEN, A TIME TO ACCEPT

Rabbi Moshe Sherer had a knack for discovering the strengths in people and encouraging them to use those strengths to help others. He, with his generous compliments and ayin tovah, was a great motivator, and he gave me a sense that perhaps I had an ability to help settle disputes.

The truth is that mediating disagreements successfully is not a question of seichel or insight, but of experience. I was in business for longer than others, and there were enough difficulties and contention along the way to teach me the best methods of dealing with them. The most important lesson I learned is that machlokes doesn’t pay: It simply is not worth the time or the energy.

I quickly grew familiar with the pattern, the back and forth, the way people add conditions and stipulations just as it appears a dispute is about to be settled. I developed a new attitude as a result, feeling that it is wiser to settle at a loss and use the time saved to try to do new business.

I remember how my son once got involved with an unscrupulous partner. My son was having trouble claiming money he had lent the partner, so I tried to help out, going to meet with the gentleman. He owed my son about $360,000, but he was adamant in his refusal to discuss payment with me. He kept insisting that I was an outsider, “Lav baal dvarim didi,” he kept saying, quoting the words of the Gemara that, “You are not my litigant (and thus have no claim against me).”

In the middle of the unproductive discussion, I took his hand and asked him to step out for a moment. In the hallway, I looked at him and said, “So much time, energy, and money have already been wasted on lawyers and accountants. Give me $175,000 right now, in cash, and we’re finished.”

He was stunned at the unexpected offer, and stood there silently for a moment. Then he spoke. “$125,000,” he answered. “Okay,” I said, not hesitating for a moment. He hurried to get me a check before I changed my mind, certain that I would come to my senses and back out.

But I had no regrets. It was sweet. Even though we had lost over half our money, there was value to being done with a frustrating episode and moving on, being able to forget about the aggravation and focus on the future.

The key element in making peace is the most vital ingredient in any area of life: siyata D’shmaya. We know that mediators are partners with the real Oseh Shalom, the One Who makes peace, and without His help, nothing moves forward.

One story of remarkable Hashgachah pratis involves the divorce proceedings between a couple who had been married for many years. Both parties came from very prestigious families and, aside from money, there were valuables and precious heirlooms involved.

It took years of work to bring the two sides to an agreement, and if not for the fact that rabbanim I respected urged me to remain involved, I would have given up many times over.

Finally, it seemed like the end was in sight, and the husband agreed to give a get.

But there was a twist. He announced that he would give a halachic get, but he would not give a civil divorce, since he refused to deal with arka’os — the secular court system — something he considered assur, forbidden. It was so disheartening to be so close to our goal, yet still confronted by new hurdles.

I was ready to give up, when a young man came to see me. He was there raising funds, but while he was in my office, he gave me a personal gift, a sefer filled with chiddushei Torah from various gedolei Torah.

After he left the office, I was leafing through the sefer when suddenly, a certain piece jumped off the page at me. It was a shtickel Torah about gittin, and it included an interesting psak of Rabi Akiva Eiger. It involved a case of a husband who gave his wife a get, but did not agree to grant her a civil divorce. Rabi Akiva Eiger ruled that the get itself was not valid, since, for a get to be legally binding, all ties between husband and wife must be severed. The civil ties between husband and wife meant that there was not a complete krisus.

I immediately copied the piece and sent it to the husband. I told him that I understood his position and his distaste for the secular court system, but explained that according to Rabi Akiva Eiger, part of giving the get was ensuring that the legal dissolution of the marriage took place as well. This argument impacted him, and he agreed to give the civil divorce, accepting that it was essentially a necessary detail in the halachic get.

That was open siyata d’Shmaya, because I certainly had not been familiar with the shitah of Rav Akiva Eiger before looking through the sefer that day.

Of course, the situation became complicated again when he developed cold feet before going to court. He claimed that he was simply unable to get over his resistance to entering a secular court. In desperation, I suggested that he simply give power of attorney to his lawyer and allow the lawyer to file for civil divorce, a suggestion he grudgingly accepted.

IN time, Rabbi Sherer created an Agudath Israel Arbitration Committee to try to spare people from going to both dinei Torah and court. He himself did not sit on the board, even though he was certainly smart and diplomatic enough to have made a difference. He explained to me that since he did not really understand business, he wouldn’t be able to offer direction. Therefore, he needed me to represent him.

We dealt with all sorts of problems, such as yerushah issues, business disputes, and divorces, with the objective of giving both sides a sense of being heard and represented.

I do not generally like the term “arbitration,” much preferring to say “mediation.” Most people, I have come to realize, are decent and good, not looking to take what is not theirs. What they want is to feel like they are being heard. Success comes from going back and forth between the two sides, giving each the sense that they were heard, even though it seems like an endless cycle.

The word arbitration indicates that we rule for them, enforcing our opinion on their situation, while mediation denotes that we have heard both sides. In fact, many of the people that I mediated for are smarter than I am, running huge businesses: Do you really think an old Poilishe Yiddele could tell them what to do? It was only when I listened to both sides that I was truly able to make a difference.

In conversation with the others on the arbitration committee, I once listed the various methods of settling disputes used by Chazal and humorously suggested how contemporary litigants would respond to them.

Kol d’alim gvar — Let the disputants settle it on their own and whoever is stronger will triumph: “Oh, I’m not a fighter, that would not work for me.”

Shuda d’dayni — Discretion of the judges: “What does the dayan know about the kosher food/import/insurance business? I know better, because it’s my business.”

Chazakah — Presumption of ownership: “I was away in China, how should I know that he parked himself in my warehouse?”

Whatever idea beis din presents, there is always going to be an answer. That’s why mediation is the best way to settle problems, through allowing each side to be heard.

There are exceptions. Sometimes, too much time spent on a case can be counterproductive. When the solution is obvious to both sides, and it is just a question of pushing it through, then you don’t want to delay. It’s worthwhile to postpone a vacation or your own business meeting or personal time and get it done, sooner rather than later, because people often change their minds when given too much time to think.

I remember a situation where a friend of mine had worked long and hard to build up a business and eventually, he succeeded. He enjoyed many good years at its helm, but it ultimately became clear that the business needed young blood. He hired some new employees, who did a wonderful job, and he steadily promoted them. In time, he became irrelevant.

They approached him with the offer to buy him out. He was hesitant, since his whole identity was bound up with that business, but he recognized that they were effectively doing everything, and he was contributing very little. Their offer was not unfair.

We met for supper. I looked at my companions, the business owner and other man who was representing the employees, and said, “Gentleman, order corned beef sandwiches and wash al netilas yadayim, because by the time we finish eating, this will all be settled.”

In took very little time, because they each recognized and understood the validity of the other’s position. They conceded that it was his business and his opportunity to reap the rewards, and he understood that they were doing all the work and wanted to enjoy the profits as well. By the time we finished saying Bircas Hamazon, everyone was happy.

Another time, divorce proceedings were being held up because of a fight over the engagement ring. The husband wanted the expensive ring that he had paid for returned to him, and the wife wanted to keep it. I sat with both sides and understood that this fight was not about money.

The wife had an emotional connection with the ring, and even though her connection with her husband had unraveled, the ring was still important to her.

I explained it to her father and privately suggested to him that he lay out money and purchase another such ring, which we gave back to the husband. Once that was settled, the get went through.

Gittin, in particular, require a good mediator. It’s a situation where both sides are emotional and hurting, and there’s nothing that the secular media enjoys as much as stories of chained women and stubborn husbands. Such situations are best resolved quickly, before the mud-slinging mushrooms out of control.

I remember a heated dispute between the heads of a yeshivah who were fighting fiercely over the building. The yeshivah was splitting up, and each head felt that the building should stay with him. We eventually crafted an agreement in which one party would get the building and the other could use the name of the yeshivah going forward, considered very helpful for attracting talmidim and for fundraising.

The party who retained the building struggled to find an identity without the name that people recognized. The effort to reopen the yeshivah with a new name in the old building did not do very well, while the group who had the name, but no building, thrived. Within a short time, the obvious solution — that the homeless yeshivah would buy the building from the first party — was floated.

Fine, said the first party, you can have it for $400,000. “Four hundred thousand dollars?” the second rosh yeshivah was incredulous. “It can’t be worth more than a hundred thousand dollars. It’s shabby and dilapidated, and it’s located in a bad neighborhood.”

We, on the committee, laughed among ourselves as this new dispute reached us. “If it’s worth so little,” we asked the second party, “why were you fighting so stubbornly for it just a few months ago?”

The answer, of course, is that people tend to see things one way while they’re fighting, and quite another when the situation changes. The very same people who had been insistent that the building was so valuable during the fight were now adamant that it was worthless.

The pasuk in Bereishis (25:14) lists the names of the Bnei Yishmael, “U’Mishma v’Duma u’Massa.” The Kotzker Rebbe understood this as a hint. He said, “Mir darft herren (shma), uhn shveiggen (duma) uhn kennen fartruggen (masa) — A person has to be able to listen, to remain silent, and to accept.”

A person has to listen silently and then move on. The problem arises when it comes to moving on, because sometimes, even when a person might be able to handle the financial loss, he can’t handle the thought of losing. He gets stuck in the rut of machlokes, and he simply has no way out, held back by his ego.

I have seen this all too often, fights that start out revolving around money but end up being about a mindset: Why should you get more than me? Why should I have to apologize to you? Why should you get away with it? Or, the one we often hear, “It is not about the money, but the principle!”

This is the depth of the Kotzker Rebbe’s teaching. Being able to accept and walk away — u’masa — is critical to attaining peace. I remember an exhausting dispute between two distinguished Jews. They had both suffered as young children, running from place to place to escape the Nazis, and they had learned survival techniques under those trying conditions. They never lost that mindset of paranoia and distrust, and what should have been a minor disagreement resulted in their facing each other in court. The judge heard both sides and awarded one of them the victory, the other one forced to pay him $25,000.

I was once talking with the winning litigant, and I asked him if he was so sure that the money was his according to halachah. He admitted that he was not certain. What, I wondered, would he answer in the Next World when asked if he had conducted his business dealings with honesty?

Okay, he conceded, I was right. If I would approach the other litigant and ask for complete mechilah, he would be very grateful, and he would also give him five thousand dollars in exchange for that mechilah.

I happily went to speak with the former partner, and told him about the other’s “teshuvah” and request for mechilah. “You have nothing to lose by accepting his offer,” I said, “and besides, he will give you five thousand dollars as a gesture, so you’ve made it easier for him in yenneh velt and you will also get a bit of money.”

He did not hesitate. “For ten thousand dollars, it’s a deal,” he retorted.

I could only smile sadly and mourn the innocence that had been taken from these men when they were young. An agreement was never reached.

I was once involved in a nasty fight between two partners after Rav Dovid Lipschutz, the Suvalker Rav, asked me to help out. One fellow had lent his friend $100,000 at ten percent interest, with a full heter iska written up.

The borrower used the money to purchase inventory that he imported illegally, on the black market. He was caught, and the entire stock was seized and confiscated at customs. He felt that he shouldn’t have to pay back the loan, since it was essentially an investment in a business idea, rather than a proper loan, and he used the fact that there was interest as proof of that fact. Had it been a loan, he said, then no Yid would demand interest. Clearly, he argued, the other man had meant for the money to be an investment, and that is why he expected a share of the profits.

I went to visit the borrower in his office one day. I said, “Listen, Reb Yankel, it’s not your style to do this, you’re an ehrliche Yid. It is clear that he is right, and if you are fighting this way, then something else must be bothering you.”

He looked at me and said, “Benny, you’re right. We’ve done so many deals together over the years, and somehow, he always makes more money than I do! Even when I have lost money, he always comes out ahead! I finally have a chance to get him back, to recoup some of those losses.”

I nodded and, once I confirmed what he was really after, I offered a proposal. “I hear your frustration, and I think you should get him back, but halachah is halachah. Maybe pay him back, but fight the interest, the ten percent extra. This way, you will ‘show’ him, but it’s not like you’re stealing his money.”

He wrote me out a check for the full amount, less the interest, feeling like he’d “won” and finally had a moment of triumph over the other man. I promptly brought the check to the lender, who was grateful, too.

So much heartache could be avoided if we would do a better job of educating people as to the value of shalom. Even when people have very negative feelings toward each other, through reaching out to impartial mediators and rabbanim, they ensure that even in machlokes, there can be peace.

Rabbi Sherer was kind enough to allow me an opportunity, and in following his suggestion and trying to help, I learned so much.

Shalom is almost always within reach, but you have to really want it.

No one has ever made peace and regretted it. Those who worked and succeeded in attaining peace saw clearly how the brachah followed. It is this, shalom, that is the ultimate factor in bringing blessing to a family, institution, or business.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 985)

Oops! We could not locate your form.