Fress

Does food deserve the pedestal we’ve placed it on?

MY

mother a”h was a master chef.

I know, everyone says that about their mothers, but come on, it’s true. Ask any of the guests she hosted. Everything she served was special; every dish was perfectly textured and perfectly flavored. I woke up to the whir of the mixer and the smell of onions sautéing. I came home from school to fresh cakes on the counter and the heartiest soup on the stove.

The kitchen was my mother’s happy place, and from that place, she made others happy. Food was her love language. And naturally, it has always been my mother tongue.

And yet, food to me has always been just that: food.

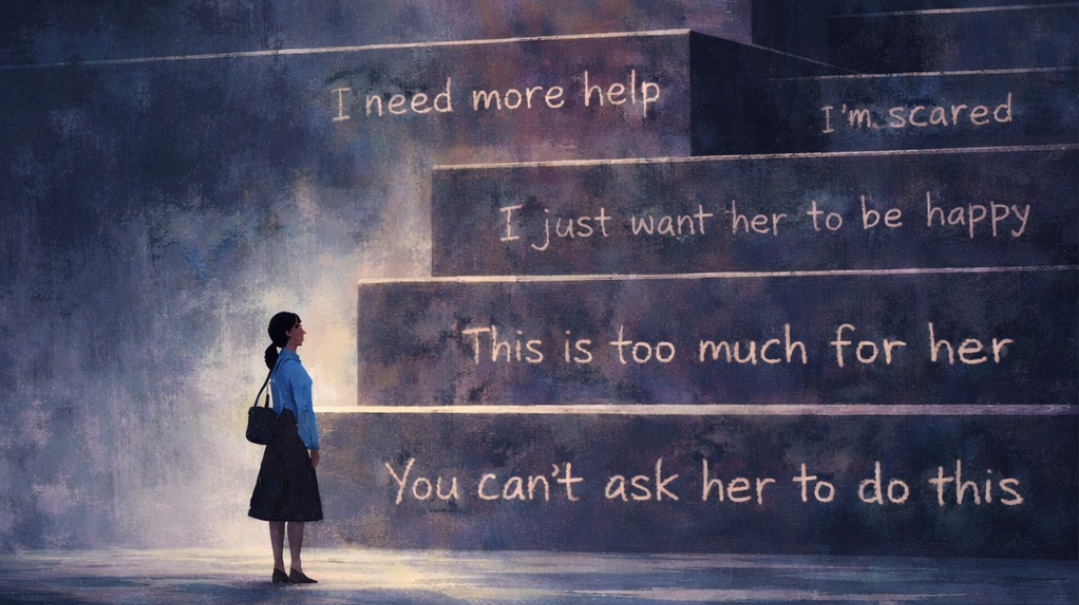

These days, it doesn’t feel like that anymore. Food has turned into something bigger. Greater. Saintlier.

It’s become a religion — and it’s followed by a generation of finger-licking worshippers.

What is it, exactly? And how did it happen?

How did we reach a point where we fall in love with a spice, revere the depth and nuance of a flavor, are obsessed with a salad component?

It’s food. It’s only food. Can we regard it as such?

Certainly, we treat food with respect. Food sustains us, and Hashem created a vast array of foods, in all colors, flavors, and textures, so it isn’t merely a source of nutrition but also a source of pleasure. We thank Him for this pleasure, and we follow the halachos pertaining to the preparation and consumption of food.

But it’s still only food. It is not the center of our existence. It is not the core of our lives.

At least, it shouldn’t be.

It’s hard to point out what exactly makes me feel queasy. I mean, I like good food — who doesn’t? I also enjoy cooking and baking, and I turn to Family Table first thing when I get my magazine every week, because, well, they have the most amazing recipes. Compared to those talented recipe developers, my skills are on the lower end of average, but not terrible. I try new recipes all the time, provided that I know how to pronounce the names of all the ingredients.

So what’s irking me?

Oops! We could not locate your form.