Forged by Fire

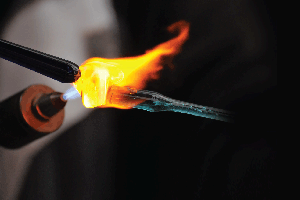

It’s the story of hundreds of boys whose lives would be transformed by both tragedy and perseverance. It’s the story of a thriving yeshivah rebuilt on American soil, confronted with a calamity that could have brought it down if not for the tenacity and backbone of its rosh yeshivah. But it’s also the story of four roommates — friends and cousins — whose destinies were intertwined within the flames that separated life from death.

Fifty years ago this week — 5 Teves, 5723, January 1, 1963 — was a day of judgment for the Telshe Yeshivah in Wickliffe, Ohio. The yeshivah, built on the shards of Holocaust devastation as its leaders shook off the horrors of their past and with steely determination rebuilt a thriving Torah center, was challenged with a major blow that threatened to undo 21 years of dedicated toil.

In 1940, Rav Eliyahu Meir Bloch and Rav Mordechai Katz (“Reb Mottel”) — son and son-in-law of the famed Telshe [pronounced Telz] rosh yeshivah Rav Yosef Leib Bloch — managed to travel out of Soviet-occupied Lithuania and make their way to the US in the hope of somehow saving the world-renowned yeshivah by transferring its students and faculty to America. Both had to leave their wives and children behind, their fates unknown. At the end of 1941, they were joined by Rav Chaim Stein, who had led a group of Telshe students in a daring escape out of Lithuania through Siberia, and reestablished the Rabbinical College of Telshe in Cleveland, Ohio.

Only two years later did Rav Katz and Rav Bloch discover that all the remaining students, faculty and their entire families had been murdered when the Nazis overran the area in 1941. Reb Mottel, who lost his first wife and a child in 1930, had remarried and had another eight children. Now he faced the staggering loss of his entire family — his wife and ten children. Despite their devastating losses, Rav Bloch and Rav Katz refused to crumble, recreating not only the yeshivah but also establishing the Hebrew Academy of Cleveland and the Yavneh School for Girls. Rav Mottel Katz, who remarried and had another three children, became head of the Telshe Yeshivah when Rav Bloch passed away in 1954. In those two decades, Telshe — which had moved to a sprawling campus in the Cleveland suburb of Wickliffe — became the crown of American yeshivos; boys arrived from all over the US, Europe, Israel, South America, and South Africa. And Reb Mottel, a master educator and forward-thinking communal activist catapulted into a new and foreign American culture, nevertheless managed to bridge the gaps with his students and inspire them in the old-world style of Telshe.

Now it looked like it was all going up in smoke.

New Year’s Inferno

4:10 am. The noise was deafening as the fire alarms split the frozen air. Flames were billowing out of West House, a converted two-and-a-half-story wooden farmhouse that served as one of the yeshivah’s dormitories on the expansive Telshe Yeshivah campus. Within seconds, blankets were thrown off as hundreds of pajama-clad students from that building and the nearby dorms ran out into the frigid winter night.

Every year on the fifth of Teves, Rabbi Chaim Amsel fingers the three melted coins still in his possession from that horrifying New Year’s Eve and remembers how he and his buddies ran out of the burning dorm and, freezing and barefoot in their pajamas, watched in shock while the entire building collapsed in a ball of flames. Two fire escapes and a chimney were all that remained of West House by the time a team of partying, drunken firefighters finally arrived from the station that was just a few blocks away.

To this day it’s a mystery how the fire started in the first-floor room; all 16-year-old Tom Schick knew was that his bed felt hot and suddenly the bed sheets burst into flames; perhaps it was an electric fire from the socket or from wiring within the wall; perhaps it was a coil heater that got too close to the bedding; investigators even speculated the possibility of arson — could drunken revelers have thrown something flammable through the window? Whatever it was, it consumed the old wooden structure in a matter of minutes, the students saved by the jarring fire alarm that Rosh Yeshivah Rav Mottel Katz insisted to be installed following a nursing school dorm fire in another city that left many fatalities.

“After the fire, a friend found the remains of the public telephone booth and broke open the coin box. Inside all the coins were melted. I keep them as my personal zecher l’churban,” says Reb Chaim, a Monsey businessman who was a 22-year-old semichah student at the time. Amsel was among the senior students at Telshe, which in the 21 years since it was established on American soil had grown to about 350 bochurim, from bar mitzvah age to their early 20s. “We all shared the same dorms,” Amsel remembers. “That was one of the Rosh Yeshivah’s policies — that we should be role models and supervisors for the younger boys.”

Jump through Gehinnom

As 64 boys scrambled out of the burning building, there was another terrifying drama playing out in what was once the most coveted room on the second floor. Four boys — Victor Sabo, Yosef Gross, Yaakov Yosef Jundef, and Avraham Shlomo Gluck — were still asleep, oblivious to the commotion outside and the crackling flames within. Avraham Gluck and Yaakov Jundef were cousins; Yaakov was just 12 — not yet bar mitzvah — and the youngest boy in Telshe, a quick-thinking whiz who had skipped two grades in elementary school.

Dr. Victor Sabo — today a dentist in North Miami Beach — was 14 at the time and a second-year student from Los Angeles. He remembers the details of that night as if he were watching it on video. “Our room was on the second floor, directly on top of the boiler room, so while the other side of the building was freezing, our room was toasty. We liked it that way and so we kept the doors closed, nice and cozy. So while the other boys were jolted awake by the heat entering their rooms, we were used to it hot. I actually slept in my underwear. We were all deep sleepers but suddenly I was awake, maybe from the fire alarm, although my father claims it was my bubby in Shamayim that woke me. I looked out the window and saw flames billowing out from the building, I screamed ‘fire!’ and then we heard the alarm and the commotion — someone must have opened our door on his way out.

“I was on the top bunk, and Yaakov Jundef was under me. He was fast as a whip and made a bee-line for the door, with me right behind him. We zoomed down the hall to the staircase — but to our horror, there was no staircase. We’re standing on the landing, the stairs are gone, and the fire is coming up to us. So right away I turned — and now Yaakov, who had been in front, was behind me. I figured we could make it to the fire escape which was back at the other end of the hall, past our room, so we ran back in the direction we came from, but the smoke was so thick we couldn’t see and the floor was so hot and we were barefoot and couldn’t even breathe anymore. And then I saw the door to my room was open, so in that split second I darted in, since I couldn’t see the fire escape … and as I jumped into the room, the hallway went down. Jundef went down ....”

Victor didn’t have time to process what he had just witnessed. The entire run back and forth probably didn’t take more than 20 seconds. Now he needed one thing — air. Choking for breath, with the flames on his tail, he ran to the window, but he couldn't budge it; it was solid ice. Thirteen-year-old Avraham Gluck, an only son, was glued to his bed, petrified and in a state of shock; Yosef Gross, a strong athletic 16-year-old, stood helplessly. The fire had already come through the bathroom that adjoined their room.

“Gross, the window!” Victor shouted, and suddenly Yosef was at his side sliding the window open. For the moment, they could breathe again.

“Maybe the fire melted the ice, but I’ll give him the credit,” says Dr. Sabo today. What happened next was what he calls “a trip through Gehinnom.”

“As the window slides up, we both stick our heads through to get some air. Our feet are starting to burn so we climb up on the window sill. Looking up, the sky is black, and looking down, it’s a pit of fire as the flames are shooting out of the building right under us. Gross and I look at each other: What are we going to do? Meanwhile the whole yeshivah was already on the ground below and they could see us in the window (we couldn't see anything), and they’re screaming ‘Gross! Jump! Sabo! Jump!’

“I’m a scrawny little kid, I’m standing there just in my underwear and it’s freezing. Gross was a big, strong guy. So he says, ‘Victor, I‘m jumping!’ ‘Okay,’ I said, ‘I'm right behind you!’ So he jumps, but I can’t see if he landed. All I know is that he jumped through the fire. Then I hear more screaming: ‘Sabo! Jump!’ So I just closed my eyes and let go. It was a long trip down. Crash. I landed on a piece of ice and cracked my heel bone. Suddenly I felt someone grab me: it was another bochur, David Tropper — today he’s a rabbi in Los Angeles — and he dragged me away from the burning building, but not before I turned around and screamed ‘Gluck! Jump! Gluck! Jump!’ But it was too late. We watched in a haze as the whole second floor came crashing down into the first floor in a burst of flames.”

Victor Sabo was the only witness. He had just watched his two roommates perish.

Meanwhile, a bochur from another dorm, 15-year-old Avraham Satz, ran outside and heard Victor scream “Gluck! Jump!” He knew someone was still in the burning building, and frantically approached an officer (“or maybe it was a fireman, but I don’t remember, it all happened so fast,” says Satz today) to rescue whoever was still trapped inside. The officer refused — he said there was no chance — but that didn’t stop Satz, who raced toward the inferno.

“The officer grabbed me by the back of my jacket that I had thrown on over my pajamas, but I wriggled out of it and kept running,” Satz remembers. “I managed to run into the building, but then the second floor came crashing down all around me. Now I was trapped and had to make a flying leap over the flames to beat a retreat.”

Avraham emerged from the building with his arms covering his face — and a trail of blood dripping behind him. He didn’t even notice that his wrist was lacerated until his friends ran over to stem the blood flow. To this day he says he doesn’t remember if it happened going in or going out of the building, but his friends told him that the door handle jammed and so he smashed the glass with his fist in order to get into the building.

“I don’t think I did anything amazing or heroic, even though I still have a scar,” says Avraham Satz, who lives in Monsey. “I just thought maybe I could help. Maybe I was an impulsive mishugeneh, but I guess I’m still a mishugeneh. I’d do it again today.”

Roll Call

“The dorm had just burned to the ground, and meanwhile we had congregated in the Mechinah building, about 200 feet away,” remembers Fishel Steinmetz of Boro Park, who was 13 and had just come to Telshe for his first zman. “The rosh mechinah, Rav Elazar Levy, took a roll call. Everyone answered, but when he called Yaakov Jundef and Avraham Gluck, there was no answer. He kept asking, ‘Did anyone see them? Did anyone see them jump?’

Even Victor Sabo, who was being bundled into an ambulance, couldn’t say for sure what happened. Was there even the slightest possibility that they could have somehow exited the building?

But by the next afternoon, as the smoldering embers receded and a crane was brought in to remove the debris, the bodies were found. Parents of the Clevelanders converged on the site, making sure their sons were safe. But two sets of parents could only look on helplessly as the crane dug through the basement rubble; it was late in the afternoon when firemen discovered the two charred bodies.

“Tuesday morning, January 1, 1963, I went to school totally unaware of the fire,” remembers Yaakov’s brother Rabbi Sholom Jundef, a posek in Rabbi Shlomo Miller’s beis hora’ah in Lakewood, who had just turned 11 at the time. Although some people in the community had already heard about the missing boys, the yeshivah had not yet broken the news to the parents. “At recess time, a rebbi approached me and told me he’d drive me home after school. When I got home earlier than usual, my mother became suspicious and called a friend who had already heard, indirectly breaking the news to her. Then one of the roshei yeshivah called my father.”

Rabbi Jundef remembers how Yaakov, the bechor of the family, memorized the entire first perek of Maseches Gittin when he was just ten. “He was in the middle of writing his own bar mitzvah drashah on Maseches Kesuvos, which the yeshivah was learning that zman.”

That afternoon, as fire marshals continued their investigation, they inspected the other buildings as well, and discovered that East House, the second dormitory which housed another 80 boys, was even more of a fire hazard that West House — promptly condemning the building.

Dressed in ill-fitting borrowed clothing from boys in the other dorms, Fishel Steinmetz remembers how all the boys lined up in the yeshivah office to call their parents and reassure them they were fine. Many of those parents, including his, were Holocaust survivors themselves, and some of the boys were their only children.

With two boys dead, one dorm burned to the ground, and the other condemned as a firetrap, there was a wave of mass hysteria and near chaos as parents demanded their children come home immediately, some driving up to Cleveland to fetch them. A hundred and forty boys had no place to sleep and over 60 of them had lost all their possessions. Would this be the unraveling of the yeshivah, the end of 21 years of rebuilding what had been so brutally snatched away by the Nazis?

But Rav Mottel Katz, the iron-willed rosh yeshivah who had lost his entire family in the war and rebuilt his life and his yeshivah from scratch, wasn’t about to buckle under.

“Genug!” he stated. “No one is going anywhere.” And with that, he laid down the law: Yeshivah would go on as usual, and no one was to leave. Whoever left would not be allowed to return.

That night, 80 students slept in the gymnasium, with cots and blankets brought in by the Red Cross. Others were farmed out to the homes of rebbeim, staff, and people in the community. All the Cleveland students had to take home a buddy. “I slept in Rav Eliezer Sorotzkin’s basement with six other bochurim until the end of the year,” says Fishel Steinmetz. The following day, the Rattner family, real estate magnates and owners of a department store, opened their inventory to every bochur who lost their clothing in the fire. Each student was outfitted with an entire wardrobe, including underwear, pants, shirts, two suits, a winter coat, and a new hat. “This was actually a windfall for me,” says Steinmetz, in a bit of morbid irony reserved only for those who’ve gone through such a trauma. “It was an opportunity to change my hat. My father z”l bought me a hat with this big brim for my bar mitzvah, but then the style was very narrow brims, and when I came to yeshivah, I was embarrassed. A friend suggested that since no one knew me there, I should just bend up the brim and people would think I was chassidish. Of course I was totally traumatized by the fire and the horrible loss of my friends, and then when we came back from the shopping we prepared for the levayah, but I can’t tell you how happy I was to get a new hat.”

The next day, after Victor Sabo came back from the hospital in a cast, he got a message that Mr. and Mrs. Gluck wanted to speak to him. He was the last one to see their son, and they wanted closure. “They wanted to know — what happened at the end? What did he do? What were his last words?” Dr. Sabo recalls what is perhaps his most painful memory of the entire episode. “I told them, ‘he kept calling out Mommy, Mommy…’ And then Mr. Gluck asked me, ‘Why didn't you grab him? Why didn’t you force him to the window with you?’ I empathized with him. I felt his pain. But what could I say? I told him, ‘The whole thing took seconds. I had no time. I couldn’t breathe. I couldn’t see. I was on the windowsill. The fire was coming right at me. You can’t imagine — it was split-second, either jump or die.’

“Afterwards, I heard that Gross, who was big and strong, felt terrible that he didn’t just grab him and throw him out the window. But I’m forever indebted to Gross. We saved each other’s lives.”

No Time for Pity

The funerals were on Wednesday. Thursday was kriyas haTorah, and the Rosh Yeshivah appointed three of the older boys, a kohein, a levi and a yisrael to bentch gomel and have in mind all the bochurim in the dorm who escaped with their lives. Rabbi Dovid Novis was the kohein, Rabbi Dovid Fine was levi, and Chaim Amsel was the yisrael. “We tend to take our lives for granted, but when I made the brachah, I realized just how thankful I was to be alive, and just how close we all came not to be alive,” says Reb Amsel. Chaim Amsel, who spent a total of 11 years in Telshe, served as the assistant general studies principal for four years before leaving the yeshivah. Yet he says he was so traumatized by the fire that for years afterwards, he couldn’t answer the telephone. The ring would make him crazy. “I couldn’t listen to it. Even after I was married, my wife had to pick it up. Every time I heard a ring or a buzz, it reminded me of the fire alarm.”

The tragedy had wide-ranging repercussions across the Torah world. The yeshivah world was devastated. The loss was frightening. Was it a gezeirah, a decree of some sort, and upon whom? A team of sofrim was brought to Cleveland from New York to check the kashrus of mezuzos, tefillin and sifrei Torah. At one hesped, Rabbi Amram Blum, the old-style European rav of the Shomer Shabbos shul in Cleveland who was outspokenly disappointed with the level of Yiddishkeit in America, pounded it into his congregation. “Why only two Cleveland boys!?” he shouted from the bimah with tears in his eyes, “Why were they the korbonos? Can we honestly say, ‘Our hands didn’t spill this blood?’ Can we say it?”

Others said that a week before the fire, the man who sold seforim out of the attic in West House sold his last copy of Raziel Hamalach, considered to be a protection against tragedy. And students noted the initials of the two names — Avraham Shlomo and Yaakov Yosef — spell aish Hashem [Hashem’s fire].

At a meeting after the fire, Rav Mottel Katz, who had lost two wives and 11 children, said, “Ich veis nisht oib di tzorah is nisht gresser fun aleh andere tzaros [I’m not sure if this tragedy is greater than all the other tragedies I’ve been through].” He said that everything that went up in smoke could be rebuilt, but the loss of life nearly broke him.

“Yet it didn’t break him,” says Reb Chaim Amsel. “He was the commander-in-chief. Right after the levayah, he announced, ‘We’re going to rebuild the yeshivah and we’re starting a campaign right now for two million dollars.’ In 1963 that was like asking for $25 million. But he undertook it and he raised it.”

A few blocks from the yeshivah, a housing project was in the process of being built, and the yeshivah rented it out before it was sold to homeowners — raw as it was. That served as the dorm facility until the new dormitory was completed. In two years, a new dorm and beis medrash were built on the land where West House and East House stood, and while Rav Mottel Katz lived to see the new dorm, he passed away of a massive heart attack in 1964, before the beis medrash was completed.

Two years after his brother’s tragic passing, Rabbi Shalom Jundef also joined the ranks of Telshers and remained there until after his wedding. He then moved to Toronto where he was part of the Lakewood kollel and served for many years as a maggid shiur. He was in Telshe during its heyday, when, on the verge of collapse, the yeshivah forged ahead and grew to over 500 bochurim.

“The strength and growth of the yeshivah was undoubtedly due to the fortitude of Rav Mottel Katz, who stood at the helm like a lioness protecting its cubs,” said Rabbi Jundef.

Dr. Sabo says the yeshivah went “from a cocoon to a butterfly. It was a special era, where we had a different kind of reverence for the old country roshei yeshivah. I don’t believe the next generation of Americans was as close to them. The culture gap was too wide.”

In fact, for Rav Mottel Katz, Victor Sabo — seated in the back of the beis medrash with his leg propped up in a cast — symbolized this resilience more than anyone. “We were given these oral exams where whoever knew the answer would shout it out,” remembers Dr. Sabo, who admits he was far from the star of the shiur. “I happened to know one answer, and the Rosh Yeshivah hushed everyone and said, “Let him answer, he’s a meyuchas. For Rav Mottel, that boy in the back symbolized all that he had lost — and rebuilt.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 438)

Oops! We could not locate your form.