For Love of the Land

A pen and a camera made Schaye Schonbrun Agudah’s man in the Knessiah Gedolah

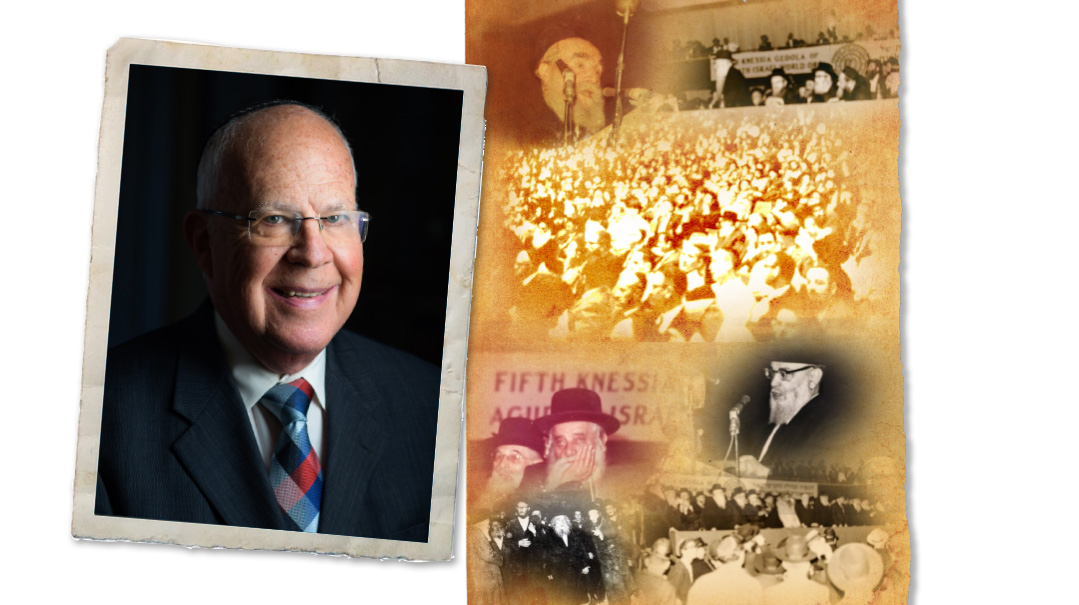

Photos: Naftoli Goldgrab, Schaye Schonbrun archives

Israel in general, and Jerusalem in particular, are so beautiful and different from our normal way of life that it is difficult to know where to begin. No picture, no matter how vivid, or story, no matter how well written, can accurately describe the life here…

(excerpt of Schaye Schonbrun’s diary)

Rabbi Schaye Schonbrun has the verve and spring in his step of a much younger man, buoyed by his passion for his vocation and his many interests. Clean-shaven, wearing rimless glasses and a kippah serugah, he spent 38 years as a principal and teacher at the Hebrew Academy of Nassau County (HANC). But back in 1964, when this diary account was written, he was a 23-year-old visiting Eretz Yisrael for the first time as a Zeirei Agudah delegate to the 1964 Knessiah Gedolah of Agudath Israel. A recent graduate of the City College of New York and a talmid of Rav Moshe Feinstein, his parents were deeply involved with Agudath Israel, and he’d inherited their passion.

His infatuation with the Land led to many trips back over the years. While he was surprised by the absolute lack of formality that characterized religious Israeli politics, he was overwhelmed by the beauty of the country and the valor of its simple people, mostly Sephardim, struggling valiantly to hang onto their emunah despite poverty and hostile opposition.

The overflow crowd at the July 1964 Knessiah Gedolah in Binyanei Haumah (left); the Gerrer Rebbe entering the convention center (right)

Reporter on the Scene

Rabbi Schonbrun poses for Mishpacha’s photographer in a black mesh fedora from Australia (“my hole-y hat,” he jokes), not the standard yeshivish Borsalino. But he’s definitely the product of an Agudath Israel childhood; his father was extremely active in Agudath Israel in his childhood shul, Zeirei Agudath Israel of the East Bronx. “I grew up in Pirchei, then Zeirei, and eventually became part of the national executive board,” he says. “I was brought to every Agudah convention by my parents from the time I was three years old.”

Their East Bronx neighborhood, later nicknamed “Fort Apache,” began to decline in the 1950s, to the point that police estimated 19 out of 20 deaths were not due to natural causes. Jewish kids had to walk two long, “very scary” blocks to get to the subways that ferried them to RJJ and Bais Yaakov. The yeshivah kids would travel together in their own subway car. As the Jewish community began fleeing the neighborhood, the Schonbrun family followed suit, leaving for Kew Gardens in 1956.

The young Schaye had a penchant for writing, and was asked to pen the Zeirei newsletters. He also was, and remains, an enthusiastic amateur photographer. When the 1964 Agudah Knessiah in Jerusalem was announced, he was sent as a delegate, traveling there with his parents, who were also delegates.

These international conferences didn’t happen often. “The very first Agudah Knessiah happened in 1910, and they had one about every ten years or so,” he explains. “This was the fourth one.” Part of Schaye’s mission included sending accounts of the Knessiah, written on aerograms, back to the Agudah in the US. He documented the trip by camera as well, producing precious photos of the gedolim who attended, and pictures of Eretz Yisrael in its early days.

The crowd at Lod Airport welcoming Rav Moshe Feinstein

Nothing to See

Traveling from the airport to Jerusalem in 1964 was nothing like it is today — no car rental agencies, no sleek train directly to the capital. The final stretch up the mountain to Jerusalem was a one lane road; when one car was going up, it would have to wait for the cars going down to pass. The buses had 21 gearboxes to negotiate the steep ascents and descents.

Schaye was initially entranced by what he encountered. “It is difficult to make oneself believe that practically everyone one meets on the streets of Jerusalem is Jewish,” he wrote. “It is hard to believe that one can walk the streets here in the wee hours of the morning and not fear being accosted or mugged.”

While his parents stayed in a hotel, Schaye and his chavrusa Lenny Greher, who would both spend the summer in Eretz Yisrael, took a room with a shared bathroom in Geula for $2.50 a night. “Back then, no one came to Eretz Yisrael as a tourist,” he notes. “There was nothing to see. There was no night life, no restaurants to speak of, only Jordanian snipers. All the streets were shuttered by 8:00 p.m. There was nothing around but the cats — and those cats were everywhere.”

Geula in 1964 was much poorer and less crowded than today. Some of the old landmarks, though, still exist; even then, you could buy Thursday night cholent in the little restaurants, and Uri’s Pizza was already open (it was the place you went to change your dollars to lirot.)

Tickets for the Knessiah were being sold for 60 lirot, with prices even higher on the black market, which was doing a brisk business. The local Agudah office was packed with people clamoring for free tickets. Coming from a background that placed emphasis on courtesy and politeness, Schaye was taken aback at the culture in Israel.

“When my camera needed a repair, I took a bus to Tel Aviv where I could get it fixed,” Rabbi Schonbrun recalls. “When I got back to the central bus station I saw a man in religious garb with an umbrella. ‘Who needs an umbrella in Eretz Yisrael in June?’ I thought. When the bus driver opened the door to let people in, it became clear why. He’d brought an umbrella to assure unimpeded entry onto the bus.”

During the Knessiah itself, his attempts to take pictures of the gedolim were interrupted by people threatening to break his camera if he did not desist. But the young man from Fort Apache had learned something about defending himself. “I told them in my best broken Yiddish, ‘I have a knife in my pocket!’” Rabbi Schonbrun says with a grin. “They then backed off, muttering ‘meshugeh Americaner.’”

The American delegation in caucus

Simple Faith

For Schaye, the highlight of the trip wasn’t the Knessiah itself, but rather the tours organized to take the foreign delegates around the country to show them the accomplishments of Chinuch Atzmai and P’eylim, as well as the immense need for more support. He noted:

Traveling through the countryside with representatives of P’eylim and Rabbi Chaim Uri Lipshitz of the Jewish Press …we traveled to Afula, a part-Arab town, and were taken to a small, broken-down shack in the middle of nowhere. This, we were told, was the only yeshivah in the vicinity. It was a Chinuch Atzmai school, funded by Agudah of Crown Heights. On the inside were two stuffy little classrooms containing beat-up desks, plus a small room with two tables, possibly used as a dining room. A few miles down the road, we were shown the government school of the area, a magnificent structure of glass and marble. The contrast was shocking.

Next they were taken to an apartment building in Nazareth, eight stories built into a mountainside, that looked impressive on the outside yet housed dismaying poverty inside. The residents, all of them Moroccan immigrants who had arrived within the last year and a half, had to squeeze their large families into three small rooms. “Many of the children sleep on the floor; the rest, four to a bed,” Schaye wrote.

These olim, who’d been religious in Morocco, were continually thwarted in their attempts to find a place for a shul:

Desperate, they remembered an old Ottoman law, which was obviously still in effect, that declared if a sefer Torah were to be placed in a room, it could not be removed. So they broke into a vacant apartment and placed a sefer Torah in it. The apartment was then used as a shul for several weeks until the police learned about it and forcibly removed the Torah, despite the law. Not giving up hope, and accustomed to persecution in their land, they broke into another apartment and used it as their shul until it too, was discovered… We were taken to visit one of these clandestine shuls in the building. We were led there by a group of children who were so happy and overcome with emotion to see religious people that they kissed our hands with tears in their eyes.

The shul was only 12 feet by 12 feet. No more than 20 to 25 people could possibly stuff themselves into the room at one time. And there were only six clandestine shuls in the entire Nazareth, serving a Jewish population of 13,000! Why? The mayor of Nazareth is fanatically anti-religious.

Schaye writes about the now-familiar yet still heartbreaking story of immigrants who arrived in Israel with no skills and couldn’t find employment, and children who ended up on the street because there were no religious schools to attend, but their parents refused to send them to non-religious schools. Many parents and even “religious” officials were bribed to entice their children to attend the spanking new, modern government schools instead of yeshivos.

A trip to Tiveria was more encouraging. There the delegates saw a P’eylim Torah center called Achuzat Naftali, “perched high atop a mountain, surrounded by Arabs and looking out over Har Tabor.” The school was run by Rav Yehuda Paley ztz”l, with great mesirus nefesh. It had five buildings, albeit with no electricity, where it housed, fed, and educated Moroccan boys in Torah and a trade. It was considered one of P’eylim’s most successful projects, yet had the capacity for only 100 boys. It seemed very clear that an entire network of such schools needed to be set up across the Holy Land.

Even in Jerusalem, our most religious city, there is a section of slums near the Jordanian border occupied almost exclusively by Moroccan immigrants who are approximately 90 percent religious with children who are 0 percent religious! We are losing the battle for Yiddishkeit even in our own backyard in the Holy City of Jerusalem.

At one point, P’eylim and Chinuch Atzmai chartered a bus to take interested delegates to a hachnasas sefer Torah for the Moroccan residents of Beit Shemesh. Rav Moshe Feinstein, Rav Yaakov Yitzchok Ruderman, and Rav Mendel Kravitz were part of the group. Schaye described the scene vividly:

As the sefer Torah was being carried from the bus to the shul, people began to emerge from every doorway to join the celebration. Young and old, boys and girls, shopkeepers and laborers…we began with about 100 people; by the time we arrived at the shul that number had swelled to 500 or more. Many boys not initially wearing kippot ran home to fetch them…the assemblage danced and sang with the sifrei Torah with an intensity found in but a few places in the US on Simchas Torah. The impression that everyone received from this momentous occasion was that, given the least opportunity, the members of the Sephardi community are more than interested in rejoining their people. Given the proper yeshivos, the proper seforim, the proper leaders, the Sephardi community would return to being 95 percent religious, instead of the present five to ten percent.

The gratitude shown by these simple people is amazing. For a neighboring community we brought along a pair of tefillin, a tallis, and a dozen Chumashim, which we presented to the rav of the town. He could barely conceal the tears in his eyes and would have kissed us all had we given him the opportunity to do so.

Schaya Schonbrun went around Jerusalem with his camera, three years before the city was united.

Staying United

July 21, 1964, just before the Knessiah’s opening, saw the arrival of a large contingent of roshei yeshivah from the US. The newspaper headlines and crackling radios bore the news to hundreds of bnei Torah, who streamed to the Lod airport to greet the roshei yeshivah. They were formally welcomed by Rabbi Menachem Porush and officials of the Israeli Agudah, accompanied by reporters flashing cameras.

As the group of dignitaries, consisting of Rav Moshe Feinstein (Mesivta Tifereth Yerushalayim), Rav Ruderman (Yeshivas Ner Yisroel of Baltimore), Rav Mottel Katz (Telshe), Rav Mendel Kravitz (Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yaakov Yosef) and a host of others neared the observation deck, the assemblage, led by New York Zeirei delegates, broke out in songs of welcome.

The crowd was huge, with at least 500 people there waiting just to see Rav Moshe Feinstein. Rav Moshe was hurried off to a side door, but the crowd followed. When he tried to exit, no one could move because of the hundreds of people surrounding him, singing and dancing. He was then returned to the waiting room, where more people jostled forth to shake his hand and sing and dance around him. He was ultimately spirited off on a chartered bus to a hotel in Tel Aviv for the night.

When the gedolim arrived in Jerusalem, they found the city bedecked with banners welcoming all the delegates. The program formally opened on Wednesday, July 22, at 4 p.m., at the mostly completed Binyanei Haumah convention center. Schaye describes the mad rush to get there, and the impossibility of procuring a taxi. At least 5,000 people jammed into a hall meant for 3,300.

Once the delegates were inside, the experience was overawing. The hall itself was magnificent, and even more importantly, it contained an extraordinary assemblage of Torah luminaries. In the first row of the dais alone, Schaye identified Rav Moshe Feinstein, Rav Yaakov Yitzchok Ruderman, Rav Moshe Katz, Rav Elya Lopian of Kfar Chasidim, the Gerrer Rebbe, the Vizhnitzer Rebbe, the Bostoner Rebbe, Rav Zalman Sorotzkin, Rav Yechezkel Abramsky, Rav Itche Meir Levin, Rav Yechezkel Sarna, Rav Baruch Toledano, Chief Rabbi Unterman, Rav Mendel Kravitz, IDF Chief Rabbi Shlomo Goren, and Rav Eliezer Silver (who arrived close to the end of the session, having been helicoptered in from the airport, unusual in those times). Rav Silver’s entry with an entourage of 200 bochurim disrupted the proceedings for a time, and so did the Gerrer Rebbe’s early exit, with a large group of his chassidim following after him.

Every gadol was accorded a chance to speak. Some speeches were in Hebrew, some in Yiddish, others in English. Rabbi Schonbrun remembers being particularly impressed by Rav Eliezer Silver.

“He walked in like the top gun,” he says. “He had such a presence with his cylindrical hat. I remember that he once came to Camp Agudah when I was there and gave a shiur for the counselors and waiters. He spoke for four hours, all from memory, not a sefer in sight.”

Rabbi Schonbrun recalls sitting at a table with his parents, Rav Moshe Feinstein, Rav Ruderman, Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky, and a couple of other friends of his parents. He remembers that Rav Moshe expressed his displeasure that he’d be separated from his rebbetzin during the Shabbos meals. Schaye, of course, was already well acquainted with Rav Moshe from the yeshivah. “I used to drive Rav Moshe to weddings in my orange 1962 Mustang,” Rabbi Schonbrun relates. “The first time I drove him home from yeshivah, he asked why the car was so small. I didn’t know how to explain that it was a sports car, so I told him that it was cheaper. He nodded, satisfied with my explanation…

“One time I picked him up at his apartment to take him to a wedding, and after we pushed the elevator button, he went back to the apartment to ask the Rebbetzin for money. ‘Ken ich hoben ah por cent?’ he asked. She opened her purse and gave him a quarter. ‘Ah shaynim dank,’ the Rosh Yeshivah told her. Everyone knew Rav Moshe never denied any request for tzedakah and would spend whatever he had. He’d often ask the bochurim in his beis medrash to lend him money so he could give tzedakah to a poor person.”

On August 3, the Knessiah concluded, having agreed on a few resolutions: to push for a five-day work week in Israel, to set up a system of yeshivah high schools under Chinuch Atzmai, largely for the Moroccan immigrant community, and to remain united. That latter achievement, according to Schaye, was largely due to the advocacy of Rabbi Moshe Sherer, who “almost single-handedly kept the Israeli factions together and prevented the American and European delegations from bolting.” The Vaad Hapoel Haolami was elected, including at least 20 American members, notably Rabbi Sherer, Rav Chatzkel Besser, the Bostoner Rebbe, Rabbi Hertz Frankel, and Schaye’s father, Irving Schonbrun.

Schaye Schonbrun returned to New York to continue his learning at Mesivta Tifereth Jerusalem, receiving semichah from Rav Moshe in 1966. He returned to Israel in 1967 immediately after the summer sessions of colleges ended, along with hundreds of other yeshivah boys and girls, to see the newly conquered territories after the Six Day War, and to daven at the Kosel for the first time. Schaye chartered a bus, hired a guide, and took four dozen young people on an unforgettable three-day tour of Yehudah, Shomron, and the Golan Heights.

Moving On

It was while he was studying for semichah and an accounting degree that Schaye Schonbrun was approached in the beis medrash one afternoon by the principal of the high school of Mesivta Tifereth Jerusalem, Rabbi Stanley Bronfeld, who informed him that he would be teaching four classes of high school English every afternoon, starting October 24. He demurred, explaining that he was not an English major and that he was devoting the next two years to preparing for semichah. Undeterred, Rabbi Bronfeld was unwilling to accept his refusal and said that the Rosh Yeshivah himself would ask him to do it. Well, it was not Rav Moshe who asked, but Rav Dovid, so they compromised on two classes at the end of each day. Before long, Schaye, now Rabbi Schonbrun, found himself the de facto assistant English principal of MTJ. After he married, he accepted a job as dean of discipline at the Yeshivah High School of Queens, which, he jokes, involved chasing boys out of the gym.

In 1976, Mr. Marvin Hirschhorn, the chairman of the Board of Education at HANC, approached him to apply for the newly opening position of General Studies Principal of HANC’s Junior and Senior High Schools. After meeting with HANC’s founder and dean, Rabbi Meyer Fendel, Rabbi Schonbrun accepted the position, serving for 30 years as a principal and English instructor. During his tenure there, in the 1980s, he also served as the president of the Principals’ Council of the Board of Jewish Education for five years.

Rabbi Schonbrun retired from the principal’s post in 2006, but stayed on another eight years as dean of students and English instructor. During his 38-year career at HANC, he had the opportunity to set many young people on the path of Torah.

“We had a program called the ‘New Opportunities Program,’ which enabled any student in any grade to enter the school in a special mechinah program as long as he could read Hebrew,” he says. “Some of these kids went from breakdance experts to tremendous talmidei chachamim. We had a Persian boy who learned to read Hebrew over Pesach in order to enter in the ninth grade, eventually going to Ner Israel. One day the mashgiach of Ner Israel called Rabbi Fendel to say they had a problem with this boy. What was it? He refused to leave the beis medrash when it closed at 2 a.m. every night.”

Rabbi Schonbrun tried to retire definitively in 2014, but found he just missed teaching too much. “I used to dream about teaching,” he says. He now teaches two classes of tenth grade English at Mesivta Yesodei Yeshurun, the high school affiliate of Yeshivas Ohr Hachaim, Lander College, and Touro University, plus two sections of Lander College Freshman English, where he shares the literature he enjoys with his students and is a spirited advocate for the proper use of English grammar. (He authored a manual, How to Teach Grammar to High School Students, as well as From Moshe to Moshe: A Short Biography of Rabbi Moshe Feinstein).

The Agudah’s resolution of unity is part of what makes Rabbi Schonbrun comfortable living in Kew Gardens. “It’s a special place,” he says. “There are seven shuls and absolutely no sinas chinam between them.” He himself davens at Khal Adas Yeshurun, the “Big Shul,” where he was one of the initiators behind the eruv in Kew Gardens in 1973 and subsequently served as president of the Kew Gardens Sabbath Council to oversee its maintenance. Since 1999, he’s been a significant force of the Nusach Sefard minyan, serving as its baal tokeia and gabbai.

While the politics of the 1964 Knessiah left Rabbi Schonbrun somewhat perturbed, it also left him with a lifelong love of Eretz Yisrael. During the year, he and his wife live not far from their daughter in West Hempstead, but they spend every summer in Har Nof near their son and his family and relish every minute. He still feels the way he did when he concluded his missives from Israel 58 years earlier:

How blessed I have been to have been given the opportunity to enter Israel, to walk through the streets of Jerusalem, to inhale the florid aromas of Jerusalem air, to wake up in the morning to brilliant sunshine and the sounds of tefillah and the singsong of learning. I try to contemplate why I have the zechus of being in Eretz Yisrael, when even Moshe Rabbeinu was denied entrance to the Holy Land…

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 921)

Oops! We could not locate your form.