Focused on Fronds

Eli Cobin’s name isn't only synonymous with the camera lens. As summer fades into Succos, he becomes “Cobin of Cobin Lulavim”

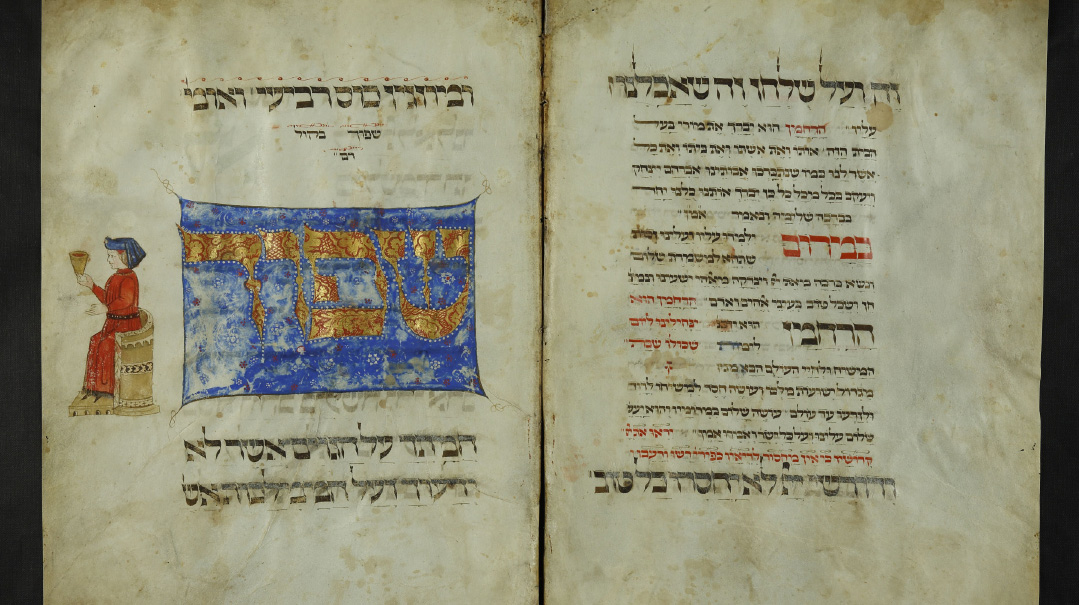

Photos: Eli Cobin, Personal archives

Say the name “Eli Cobin” and any insider on the Israeli media or simchah circuit will nod in recognition, envisioning a gangly man with a ready smile and camera, famed for his artistic portraits and vibrant action shots. But for two months of the year, Cobin’s name is not synonymous with the camera lens. As summer fades into Succos, he becomes “Cobin of Cobin Lulavim.”

Cobin Lulavim, founded by Eli’s father, Reb Shabsai Cobin, was the first distributor to sell the Deri lulav to the masses. Today, the Deri lulav — a beautiful, strong, green, and mehudar specimen — is the prime choice of virtually every Ashkenazi in Israel. “But back in the day,” Eli says, “only rabbanim had mehudar lulavim.”

Eli rattles off some lulav facts like he’s done it a thousand times before. Which he has. “The Rema rules (Orach Chaim 645:3) that l’chatchilah it’s best to have a tightly closed lulav — the tiyomes (the center leaf) shouldn’t be even slightly open — but there were few lulavim available in Europe, and it was almost impossible to find a truly mehudar lulav. Faced with little choice, people tried at most to buy a lulav that was straight and not open enough to make it passul; a tightly closed tiyomes was a luxury they couldn’t dream of.”

When the Brisker Rav arrived in Yerushalayim, word spread of his insistence on using only a tightly-closed lulav. That’s why people call a closed, green, not-sunburned specimen a “Brisker lulav.” It would be more accurately termed a Rema lulav, but it was the Brisker Rav who made it the standard.

In order to ensure the middle leaf is truly closed of its own accord and not simply held together by the outer layer, the Brisker Rav used to inspect lulavim by peeling off the kora, the brown bark-like substance that grows around the lulav. The exacting standard set by the Brisker Rav led to considerable turmoil: People began looking for closed green lulavim without any signs of sunburn, and not covered by any brown kora.

(They likely didn’t realize that the kora is there for a reason — to ensure the lulav gets the moisture it needs. Removing it too early can damage the lulav.)

“There are nine date species that grow naturally in Israel,” Eli explains. “Chiyani, Barhi, Chadro’i, Chalou’i, Deri, Zehidi, Dekel Nur, Medjool, and Imri. Back when my father started out, there were only about 4,000 Deri date palms in all of Eretz Yisrael and since each tree yields about three to four lulavim, that makes about 12-16,000 lulavim. Certainly not enough for the needs of all of the Torah-observant community.”

It was a classic case of high demand and inadequate supply. Everyone wanted a Brisker lulav, but there simply weren’t enough on the market.

Then Shabsai Cobin came on the scene.

“Abba was an American baal teshuvah who moved to Eretz Yisrael and never looked back,” Eli says. “He loved this country with everything he had, and he was determined to benefit from all it had to offer. Back in the 1980s, Abba started searching for a Brisker lulav. He searched for the perfect lulav in all the different kibbutzim in the north and eventually arrived at the religious Kibbutz Tirat Zvi in the Beit She’an Valley, only 500 meters from the Jordanian border.”

Beit She’an is in a fiercely hot area not far from the Kinneret. Drive along the highway and you’ll quickly realize that it’s prime palm territory — rows upon rows of palm trees extend from the roadside deep into the farms and kibbutzim that dot the region.

“Abba examined the different palm trees growing there and ascertained that no other species comes close to the Deri lulav in hiddur. It was a real beauty and very strong. There were some other species whose tiyomos were closed, but they ended in a pinpoint — which meant there was a real risk these narrow tips were fragile and might break, resulting in a halachically disqualifying condition called ‘nifsak rosho.’ ”

Reb Shabsai bought 300 lulavim at five shekel a piece, and traveled in an old, battered car to the famed Lederman shul in Bnei Brak. He first started selling his merchandise for the bargain price of 20-30 shekels (five to seven dollars) apiece. People could not believe their eyes — the quality was astounding.

Reb Shabsai decided to set up shop in Jerusalem and rented a store in Meah Shearim. But he still made stops in Bnei Brak every year — his first place of business and perhaps his most beloved.

Oops! We could not locate your form.