Flight for Freedom

| June 6, 2023Fifty years ago, these refuseniks tried to hijack a plane — and they're still soaring

Photos: Menachem Kalish, Mishpacha archives

ITwas June 1970, and after decades of Soviet oppression, a small band of Jewish refuseniks decided to hijack an empty propeller plane and steer it out of Soviet airspace. Fifty-three years later, some of those “hijackers” — retirees living in Israel after imprisonment in the Soviet Gulag — retell the story that gripped the world and opened the doors for thousands of others to fly away

The early 1970s were fraught with a veritable epidemic of skyjackings for political or financial gain. Between 1968 and 1972, over 130 US aircraft alone were overrun by hijackers holding planeloads of innocent passengers hostage while demanding ransoms, the freeing of terrorists, or political asylum. But those who are old enough surely remember a particularly noble and courageous hijacking plan with a very different agenda — one that would change the face of the Soviet Jewry movement and create so much international pressure that the locked gates of the Iron Curtain would finally open.

Fifty-three years ago this week, a small band of Soviet Jewish refuseniks attempted a daring — if improbable — escape to Israel. The Leningrad hijacking plot — known as “Operation Wedding” — is a powerful modern-day story of courage and commitment by a group whose Jewish identity was just beginning to reemerge after decades of Soviet oppression.

It was 1970, three years after the Jewish State’s miraculous victory in the Six Day War. While anti-Israel propaganda was fed to the Russian proletariat, news of Israel’s supernatural successes had made its way into the consciousness of Soviet Jews and ignited a new passion, firing up the sparks of nearly-extinguished embers. Underground, clandestine classes in Hebrew language and Jewish tradition were organized, and many idealistic young people began to apply for exit visas in order to escape the grip of the Russian bear.

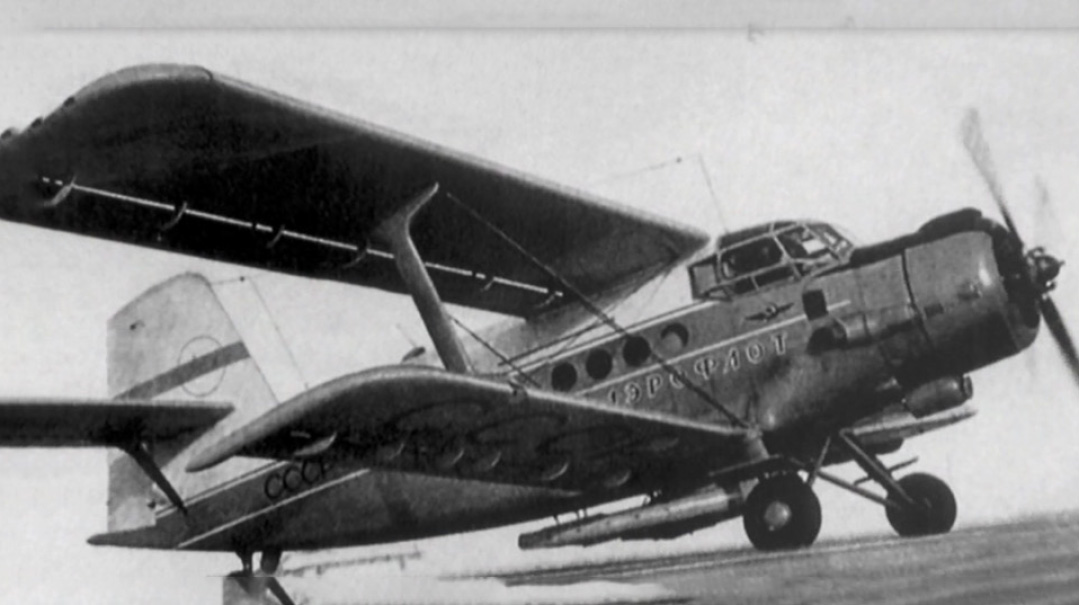

After having been refused visas and stripped of their professions (the general fallout for applying for a visa), a group of 16 dissidents plotted to buy all the seats on a small 12-seater Antonov An-2 propeller plane, make a local flight from Leningrad to Priozersk under the guise of a trip to a wedding, remove the pilots, and continue across the border to Finland and then on to Sweden, with Israel as their final goal. On the morning of June 15, 1970, 12 of the group arrived together in Smolny Airport near Leningrad (another four were to be picked up in Priozersk), only to land in the waiting arms of the KGB, who’d been tailing them all along.

It wasn’t a Antonov An-2 propeller plane, but that didn’t stop Soviet Jewish heroes Arie Chanoch, Wolf Zalmanson and Boris Penson from climbing the light craft on the Herzliya airfield last week, bringing back memories of half a century when the eyes of the world were focused on their future

While the “hijackers” were convicted of high treason and all served long, harsh prison sentences in the Soviet Gulag, due to international pressure they were eventually released, and by drawing attention to Soviet human rights violations, their long-term goal — the loosening of emigration restrictions — was realized.

Three of those “hijackers” — men in their 70s who’ve been living in Israel for decades — came together for a conversation of memories with Mishpacha in advance of June 15, the anniversary of the day that would change their lives — and those of the entire refusenik community — forever.

“For years, the Soviets continued to label us as hijackers, terrorists, cold-blooded murderers. Those accusations still appear in the KGB records. But who cares?” says Wolf Zalmanson, who was sentenced to ten years in a Soviet prison and today lives in Herzliya, retired from a long and successful career in Israel’s aerospace industry. “We’re home, in Eretz Yisrael. They can say what they want.”

He’s joined by Boris Penson, today a well-known artist and resident of Moshav Hoglah near Netanya, and Arie Chanoch of the Shomron, all of whom agree that their personal sacrifice was worth it for the hundreds of thousands of Jews who were able to leave the Soviet Union in the wake of the operation and ensuing politically charged trial — the inspiration for several suspense novels and films, the background of several autobiographies, and even the incentive for a popular Destiny song.

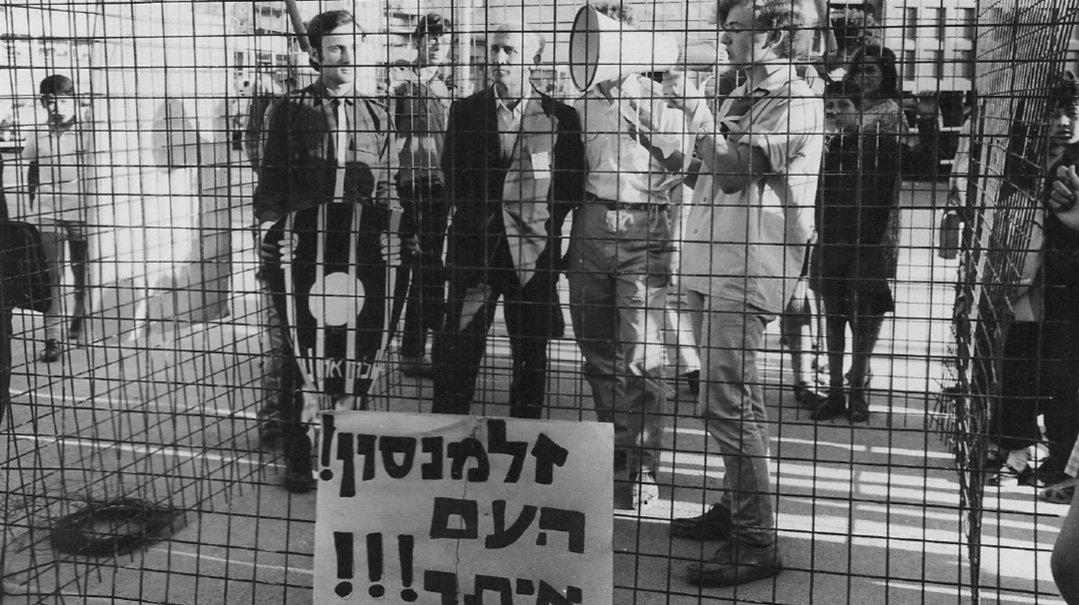

The group knew they were being tailed and that arrest was inevitable, but they were banking on pressure from around the world – and thousands of demonstrators didn’t let them down

AT

the time, these three pensioners were among so many others who envisioned an impossible and unrealistic dream.

Boris Penson, then a 23-year-old aspiring artist, was kicked out of Riga’s art academy during his freshman year after he applied to emigrate to Israel and was refused. But, talented as he was, getting the boot from the academy while being refused permission to emigrate meant the end of his professional future.

“I had submitted a request for an exit visa to make aliyah,” Arie (Leib) Chanoch, who was 25 at the time, relates, “even though we knew that just submitting a request meant we’d be labeled as ‘disloyal to the party’ and an ‘enemy of the people.’ But as expected, my request was denied.”

And yet, even the world’s biggest superpower had some weak spots. A few days after Arie submitted his aliyah request, he suddenly heard from his brother- in-law, a young refusenik from Riga named Yosef Mendelevitch (Yosef’s sister Meri a”h was married to Arie) that there was a group of Jews seeking to leave in an original — if not delusional — fashion: They were planning to hijack a plane and to flee from Russia.

“At first I thought it was a joke,” remembers Arie Chanoch. “The plan had all the components of an immediate death sentence: hijacking a state possession, leaving the country illegally, and treason. But as the days passed, I discovered that those who were behind the plan thought there was an outside change it could actually work. They knew they could be shot, or if they were fortunate merely arrested, but were still hoping for a miracle. They also hoped that in case of arrest, public opinion and pressure from world Jewry would bring about their eventual release.”

The meetings became more frequent. Mendelevitch — one of the most prominent Prisoners of Zion who subsequently spent 11 years in the Gulag where he was continually tortured for his religious observance and who today is a rabbi living in Jerusalem — was the liaison between the members of the group, some of whom lived in Riga, and others who lived in Leningrad.

Riga’s young Jews were born just a few years after Latvia was annexed to the USSR in 1940. Most of them grew up in traditional Jewish families, who had avoided several previous decades of Soviet decrees against religion. One of the main faces of the plot, and the only woman to serve a prison sentence afterward, was Sylva Zalmanson, Wolf’s sister, who received a basic Jewish education at home and had spent the previous five years disseminating Hebrew language study books to Jewish communities around the country and listening to Israel Radio broadcasts in Russian.

A month before the “hijack,” she married 31-year-old Eduard Kuznetsov, who was both a professional wrestler and student of philosophy who joined the Soviet Army in the hope that he would be stationed abroad and would be able to escape his country, but ended up being posted in Moscow. He was arrested at the age of 22 after editing an underground anti-Soviet newspaper and was sentenced to seven years of forced labor in Siberia. After his release, he settled in Riga where he heard about Jewish underground activity, and where he met and married Sylva.

Sylva twice applied for an exit visa — the first by herself and the second together with her new husband, who, as a former political prisoner, remained under the scrutiny of the KGB — and was rejected both times.

“You will rot here and never see your Israel,” she was told.

Zalmanson, her husband and her two brothers, Wolf and Yisrael, were among the 16 members of the group. (Another brother, Shmuel, was the only sibling who didn’t participate, and they made sure their father, who had a senior government position, knew nothing about it. It didn’t help, though. The day after the arrests, he was fired from his job.)

“At home, we always had a dream to make aliyah,” her brother Wolf relates. “We knew that we had no future in Russia. We learned Hebrew secretly and also learned a bit about Judaism, but everything we learned was at tremendous risk.”

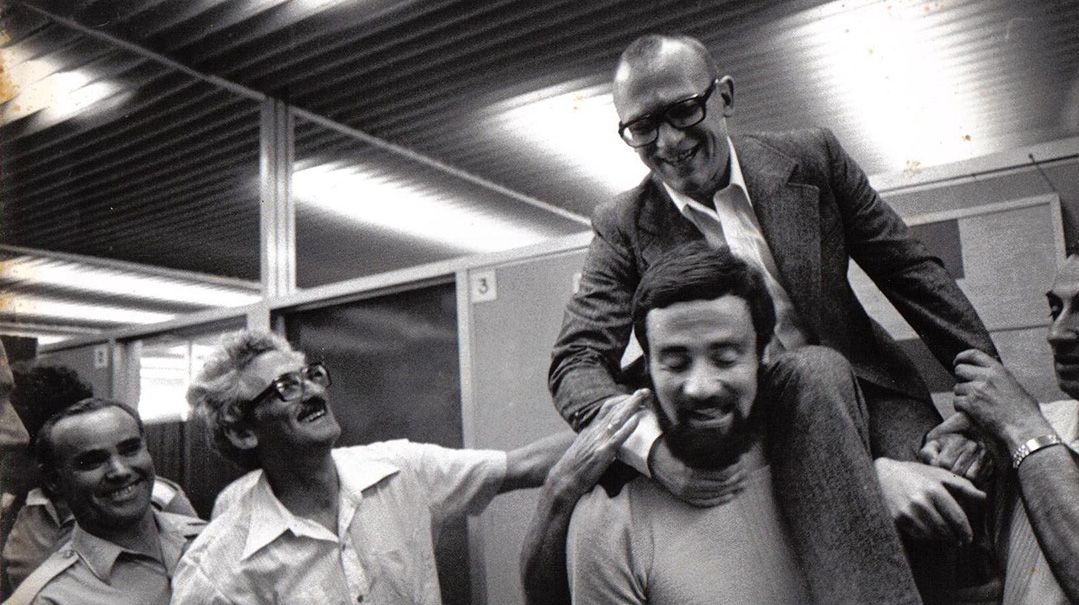

Boris Penson and Wolf Zalmanson in a joyous embrace with then-opposition leader Menachem Begin. “It’s much easier to serve time when you’ve done something you can be proud of”

Wedding Preparations

The plan the group settled on, dubbed “Operation Wedding,” was to book all the tickets on an An-2 12-seater propeller plane that flew twice a week from Leningrad’s Smolny airport to Sortavala on the Finnish border with a stopover in Priozersk, a small town on the western shores of Lake Ladoga. It was a marginal route, so security wouldn’t be as heavy, and Finland was just a 15-minute flight away.

Mark Dymshits a”h, a 43-year-old demobilized military pilot who was grounded when Jews were fired from the aviation industry and realized there was no future for him in Russia, had experience flying the An-2s and was brought on board by Riga’s refusenik underground (Dymshits passed away in Israel in 2015). The plan was that at the stopover in Priozersk, they would tie up the pilots and leave them outside in sleeping bags so they would stay warm.

“We were very concerned about the pilots,” Zalmanson says. “Our plan was to be as kind to them as possible. We would remove them from the cockpit and leave them next to the airport with sleeping bags, a tent, and a few bottles of vodka.” Dymshits, the pilot, would take control of the plane and fly it under the radar across Finland to the Swedish town of Boden, where they would give a press conference — they were afraid to land in Finland because it was known to hand Soviet asylum-seekers back to Russia. And even if they’d be arrested in Sweden, they figured it would be a pit-stop of a maximum of a few years on their way to Israel.

Because the An-2 had only 12 passenger seats and the group had 16 members, they split up. The main group, which would initially fill the plane, included Dymshits, Kuznetsov, Mendelevich, Sylva Zalmanson’s brothers Wolf and Yisrael, Anatoly Altman, Mendel Bodnya, Dymshits’ wife Alevtina and their two teenage daughters, and two non-Jewish friends of Kuznetsov’s from his years in prison camps, Alexei Murzhenko and Yuri Fedorov. The remaining four — Sylva, Penson, Chanoch, and Chanoch’s pregnant wife Meri — would board at the stopover.

This nucleus group was especially brave and daring, considering that they’d just gotten a cold shoulder from Israel. An outline of the plan had been secretly transmitted to government officials, but the Israelis were afraid that the plan would fail, leading to a wave of arrests, the liquidation of the underground that worked in the Soviet Union in those years, and an end to emigration entirely. While the message out of Israel was a searing disappointment, the group went ahead in any case.

IT

seems that from the very early days of the plan, the Soviet KGB was a full partner. The agents followed the meetings, listened and documented them. Even before the planned operation, the group realized they were being tailed.

How did the KGB know? “In Russia, if three people know something, then the KGB knows about it,” Zalmanson says. “Here, at least 100 people knew about it.”

There is another theory as well, that the entire plan was actually a KGB trap. “They opened a new flight route from Leningrad to Finland and made sure to convey that information to pilot Mark Dymshits,” Zalmanson notes. “It turned out that the agents knew everything about us, even which wine we preferred. There wasn’t a detail they didn’t know.”

As 12 members of the group walked out onto the tarmac in Smolny airport near Leningrad, waiting for the planes to open their doors so they could take off for their next stop, the doors did open — and armed KGB agents emerged, firing into the air. Within seconds, everyone was handcuffed and led to the black vehicles that were waiting a bit further in on the airport grounds.

They claimed that already on the way to the airport, they had realized their fates were sealed. “It was clear we were being followed, but we decided to continue,” Eduard Kuznetsov later related, explaining why: “If you start something, you have to carry it through. And it’s much easier to serve time when you’ve done something you can be proud of.”

“We knew there was no chance,” Sylva Zalmanson would later relate in testimony that was presented in the 2015 documentary “Operation Wedding,” created by her daughter Anat Zalmanson to set the record straight and counteract the Soviet version of the operation, which is still officially disseminated by the Kremlin. “We knew that the plan would fail, that they would fire at us before we got to the plane, and if we’d manage to take off, they would bomb us from the air. But we also knew that no matter what, we would attain our goal: If we were able to leave, that would be great, but even if we didn’t, we would generate an international scandal that would expose the suffering of the Russian Jews to the world.”

Sylva said that although they saw the signs — on their way to Leningrad they knew their checked luggage had been searched — they decided to continue.

Wolf Zalmanson adds, “A week before the planned flight, Dymshits and Kuznetsov traveled on the route. During the flight, they saw that some of the passengers were KGB people. But we still didn’t consider cancelling our plans. We knew we’d be arrested. We knew we might be shot. But we had no choice. When a person is living in a prison, he wants to escape at any price. But more than that, we were hoping for an international outcry, so it was worth getting caught. Only in this way, we knew, would the world learn about the plight of Russian Jewry and get involved, which is, in fact, what happened.”

The moment of the failure is something Wolf Zalmanson will never forget. “Just a few steps before we boarded the plane, armed agents burst outside, and a second later I saw Dymshits led by two policemen, his clothes stained with blood. I looked up, and I knew that this was the last time I’d be seeing the sky above me without bars for a very long time.”

Arie Chaoch was waiting at the stopover in Priozersk. He and the other three in his group already knew the plan was doomed when their KGB tails on the train to Priozersk didn’t even try to hide themselves. They were arrested in the middle of the night while waiting in the forest near the airfield, hours before the plane was even scheduled to arrive. Soon the entire group was inside the Leningrad KGB prison, where they would spend the next six months in pretrial investigations before the December trial that would shake the world.

Eduard Kuznetsov — after two long prison terms in the Gulag — upon his arrival to Israel, on the shoulders of his brother-in-law Yisrael Zalmanson

Prisoners of Conscience

Of course, the planned press conference on Swedish soil never took place. Instead, the Russian government presented the fleeing Jews as “terrorist hijackers” for all the world to hear. “Operation Wedding” remained in the Soviet headlines for weeks, the group members depicted as brutal terrorists who were willing to murder the pilots and take control of passengers, because they wanted to flee the Soviet “garden of Eden.”

The “hijackers” were put on trial for their dastardly plan: to kill the pilots and the crew, to take passengers hostage, and then flee the country. The court case was based on “testimony” that amounted to 8,000 pages of investigative materials, taken from hundreds of “witnesses,” depicting the entire broad community of Russian Jews as supporters of terrorists.

The accused were charged with high treason, punishable by death under Article 64 of the Russian penal code. In the trial that took place for a week at the end of December 1970, Sylva Zalmanson, the only woman on trial, was the first to take the stand. The KGB expected that she, as a woman, would break first and beg for a pardon, but to their surprise, she didn’t ask for clemency at all.

On the contrary, she looked the judges in the eye, making it clear that she had no regrets. “If you had not deprived us of our basic right to leave the Soviet Union, we would have simply purchased airline tickets to Israel,” she told the court. “Even now on the defense stand, I believe the day will come when I will be in Israel. A faith that has lasted 2,000 years is still giving me hope.” She then recited the words of Tehillim 137: “Im eshkacheich Yerushalayim tishkach yemini. Leshanah haba’ah b’Yerushalayim!”

The stunned judge asked for the translation of the words, and she complied. Silence ensued. The entire court, filled with hundreds of curious “civilians” (planted by the KGB to make it appear like it was an open trial), was speechless.

The Russian government, though, was hardly impressed at that time. At the end of the trial, the verdicts were handed down: Mark Dymshits and Eduard Kuznetsov received a death sentence by firing squad. Sylva Zalmanson received ten years; Yosef Mendelevitch and Yuri Fedorov, 15 years; Aleksey Murzhenko, 14 years; Arie Chanoch, 13 years; Anatoli Altmann, 12 years; Boris Penson, ten years; Yisrael Zalmanson, eight years; Mendel Bodnya, four years. Wolf Zalmanson, at the time an active-duty officer in the Soviet army, was tried separately by a military tribunal and received ten years.

“I didn’t think about my own punishment, I thought about Eduard, my husband, who was going to be brutally murdered, and although I was panic-stricken, he was actually rather calm,” Sylva later related. “From his place on the stand, he smiled at me, and made a motion of wings with his hands, as if he was an angel who was going to fly up to the Heavens.”

The harsh sentences led to a storm around the world. In the United States and Europe, mass demonstrations were held outside United Nations offices and Russian embassies. Mass tefillah rallies were held at the Kosel as people prayed for the release of the Prisoners of Zion. All over the world, tens of thousands of people took to the streets with the slogan, “Let my people go,” while world leaders appealed to Communist Party secretary Leonid Brezhnev with a demand to commute the brutal death sentences.

Within a week, facing tremendous international pressure, the Soviet regime commuted the death sentences for Dymshits and Kuznetsov and reduced some of the others’ sentences by two to five years.

Furthermore, strong international condemnations caused the Soviet authorities to significantly increase their emigration quotas. Whereas in the years 1960 through 1970, only about 4,000 people had been permitted to emigrate, in the decade after the trial — from 1971 to 1980 — close to 250,000 Jews were permitted to emigrate. (The gates reopened for good with the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989.)

In conversation with our three “ex-hijackers,” we learned that Israel had a sneaky hand in the reduced sentences as well, betting on Brezhnev’s ego.

“Golda Meir,” Arie Chanoch relates, “reached out to Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, urging him to cancel the death sentences he’d imposed on six Basque terrorists who had carried out attacks in Spain. ‘You have Jewish roots, you come from a family of Anusim,’ Golda Meir told him, making it clear that if Spain would display a humanitarian side and would nullify the death sentences, Brezhnev would not want to be perceived as crueler than Franco. He would also have to follow and commute the death sentences of the two Jews. Indeed, Franco acceded, and right after that, Russia announced the cancelation of the death sentences.”

In the years that followed, even prison sentences and harsh labor did not depress the spirit of the group, who recognized that their actions had jump-started a wave of aliyah and a renewed dedication to their plight.

Sylva Zalmanson spent half a year in solitary confinement in a freezing Siberian prison cell after hitting a prisoner who hurled anti-Semitic slurs at her. Her husband, Eduard Kuznetsov, actually began to write a book on tiny scraps of paper that he’d swallow and then spit out at meetings that he was granted with a Jewish scientist who professed to be his aunt.

“In the end,” Penson says, “the operation achieved its goal. We made a tremendous amount of noise in the media that shed light on the plight of Russian Jews. The evil we were subject to woke up the world.”

The ongoing demonstrations in Jewish communities around the world didn’t go unnoticed. Four years later, Sylva was released in a prisoner exchange with Israel, swapped for apprehended Soviet spy Yuri Linov.

“In truth,” Sylva says today, “I didn’t believe we’d succeed in leaving. Everything had closed in on us from all sides. I was in solitary confinement and didn’t think I’d ever get out. More than anything, I dreamed of children. I used to gaze at the cats and be jealous: They merited to raise offspring, while I would rot in this cell for the rest of my life. But in the end, we came to Eretz Yisrael and I did merit it. I have also merited to see the next generation.”

Before her release, the Soviets demanded that Sylva Zalmanson express regret, but she refused. The KGB interrogators threatened that her release would be canceled, but she stubbornly refused to express remorse. Then they wanted to show that her release was for humanitarian purposes, and suggested that she ask for clemency due to her health. “If you ask for clemency, we’ll also give you an exit visa to Israel,” they told her. But she refused this as well. Even though she knew she could be sent back for six more years in prison, she retorted, “I will never ask you for anything.”

The Soviets had no choice. They had already committed to her release, and she was set free. But she refused to leave before she could visit her husband and two brothers, whom she had not seen in four years. Surprisingly enough, her firm stance made the KGB bend, and she was allowed to meet with her husband.

News of her release spread rapidly in the Jewish world; the sight of her on the stairs of an El Al plane in Ben Gurion Airport, as thousands waited for her bearing flowers, moved the Israeli public to tears.

Sylva didn’t waste any time. She immediately went to work to gain the release of her family members and the others, a protest that culminated in a hunger strike in front of the UN in New York. The strike last 16 days, during which time she was surrounded by thousands of supporters, including senators and government officials who came to show their solidarity and support in her struggle to release her husband and the rest of the group.

After two weeks of not eating, she collapsed and was hospitalized. The sight of her collapse, and the emergency care she received in front of the UN, attracted extensive media coverage and led to international pressure on the Kremlin. But it took another several years for the first cracks to appear. In 1979, in secret spy swaps and prisoner exchanges, Penson, Hanoch, Altman, Wolf Zalmanson, Kuznetsov and Dymshits were released. Among his fellow Jews, Yosef Mendelevitch served the longest — 11 years out of the 15 ordered by the court. He was released in 1981.

“We were at a certain point in history that enabled a few individuals to have a great influence,” Eduard Kuznetsov summarized years after his release, when he headed the news department of “Radio Liberty” and became editor of the Russian-language newspaper Vesti. “We were able to rock the Soviet boat a bit and to get it to change course.”

More than half a century later, they look back at their decade of suffering: True, “Operation Wedding” never got off the ground, but the skies eventually opened. It took another two decades until Sylva Zalmanson’s defiant declaration on the defense stand in the courtroom in Leningrad, Leshanah haba’ah b’Yerushalayim, became the reality for hundreds of thousands of Jews whose dreams really did come true, and who have come home — who would have believed it then — to Jerusalem.

Rachel Ginsberg contributed to this report.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 964)

Oops! We could not locate your form.