First Port of Call

Of course, this is not the first time in history that the Jewish people had challenges coming in to Eretz Yisrael

Photos: Menachem Kalish

While we can’t compare ourselves to the gibborei koach — the holy farmers who have put down their tools during this shemittah year — we tour guides have also had our “shemittah” year while the skies closed. Now, baruch Hashem, the gates are opening and the tourists are beginning to trickle back. Of course, it’s not the first time in history that the Jewish people had challenges coming in to Eretz Yisrael. Today we’re going to travel through time and space and visit some of the ancient gateways to the Holy Land while we connect to the mesirus nefesh our ancestors had as they made their way to these shores. And then a few ishurim from the Interior Ministry and a booster shot might not seem so daunting after all.

Grand Entrance

There’s no better place to start than at the point of our first national entrance to Eretz Yisrael, crossing over the Jordan River from the Plains of Moav in the year 2488. We head into the Jordan Valley on Highway 90 (Israel’s longest highway, going from Metulla in the north all the way down to Eilat) until we get to a site not far from Yericho, known as Qasr al Yahud.

The site we are arriving at was renovated by the Ministry of Tourism in 2011 to serve the many Christians that come here to dip in its “holy” waters as they believe the founder of their faith did. It’s been a baptismal site for centuries, and there are remains here of ancient churches dating back to the fifth and sixth centuries when many monks came out here for meditation and solitude. The name Qasr al Yahud actually means “palace of the Jews,” although the “palace” is a reference to the huge nearby monastery, and the “al Yahud” part is the reason why we are here. This has traditionally been identified as the possible crossing place of Klal Yisrael into Eretz Yisrael, and we’re here to claim it back.

Tourists are often a bit confused and disappointed when they come here. For as we approach the Yarden, all we see in front of us is a small little creek that seemingly could be hopped over even by a child. There is a rope on the water, the kind separating lanes in a swimming pool, and that’s the border between Israel and Jordan. Two young chayalim are posted on our side and we wave to the Jordanians on the other side, less than a stone’s throw away. “This was the big deal, the groyseh Yarden?” tourists inevitably ask me. Well, yes, but the Yarden we’re looking at today is in fact only two percent of what it once was even a half a century ago. Whereas before the establishment of the State of Israel it is estimated that 1.3 billion cubic meters of water flowed down the river annually, today that number has shrunk to 20-30 million cubits. Over the past 70 years, both Israel and Jordan — and even Syria — have been building dams and diverting and drawing water from the Jordan River for their respective country’s needs.

But let’s for moment step back in time about 3,300 years. On the other side of the Yarden would be standing over a million of our ancestors scratching their foreheads and wondering how they were going to get over the huge raging river in front of them. Moshe Rabbeinu had died a little over a month before on 7 Adar. Yehoshua had sent in spies a few days before to the city of Yericho just north of where we’re standing, and they get the all-clear that the land would be conquerable. Yet now, in the month of Nissan when the river is at its highest point, picking up the melting winter snows of the Chermon, they’re faced with the question: How will they get in?

Yehoshua reassures the nation that it will be a day of miracles. He chooses one man from each tribe along with the Kohanim and those who carry the Aron HaBris and commands them to cross the Yarden, assuring them that as soon as their feet touch the waters it would split. The nation followed and indeed the waters split. On the southern end the river continued to flow down to the Dead Sea, while the northern part of the river stood straight up in the air like a geyser flowing up to the sky — either 12 miles or a whopping 300 miles high, according to various opinions. The Jews then selected 12 large stones from the Yarden that they carried up to Har Gerizim and Har Eival and wrote the entire Torah upon it in 70 languages, as commanded by Moshe before he died.

As we leave this site we make the brachah of she’asah nissim l’avoseinu bamakom hazeh. The miracles we refer to are, of course, crossing the Yarden, but others took place here as well. For it is here that Eliyahu Hanavi ultimately split the river with his student Elisha (who in turn split it as well) before ascending to Shamayim, and where Naaman was healed from his tzara’as. The first lesson we learned here as a nation is that there is no natural way to come into Israel. Even today, if we manage to make it in, we were meant to know that it will always be miraculous.

Battling an Angel

Our next stop further up the road might be a bit nondescript. We stop near what was formerly a bridge between Jordan and Israel, known as Gesher Adam. This crossing dates back over 700 years to the period of the Mamluks, when their leader Sultan Baibars built the bridge in order to facilitate travel between Amman and Shechem. It was later fixed up by the Turks, and later the British and Jordanians, until it was put out of commission in the 1970s for private travel between the countries and shut down in the ‘90s for commercial transport as well.

There’s not much to see here today besides a closed army site, but the reason we’ve stopped here is because this as well was a crossing place for our ancestors. We are opposite Shechem in the Shomron mountains above us, and Nachal Tirtzah flows down the mountain, depositing its waters into the Yarden. But it is the other side of the Yarden that is more significant to us. For it was there that Yaakov Avinu, after 20 years of galus by Uncle Lavan, and brought his children for the very first time into Eretz Yisrael. In fact, when the Yarden splits for the Jewish people centuries later, the Navi tells us that it split all the way up to “Adam,” which is the name of an ancient tel about a kilometer from here. The city of Succos, which Yaakov Avinu built for his animals right after his fateful meeting with Eisav, is not far from here as well. The Talmud Yerushalmi calls Succos “Derala,” and the similar sounding Tel Der- el Allah is right across the A Zarka river, which is commonly accepted as Nachal Yabok — the river Yaakov Avinu crossed.

Was it hard for Yaakov to get into Eretz Yisrael? The crossing itself seemed simple, according to the Midrash. He just picked up his family with one hand and made himself into a bridge to hand them over to the other side. (Hmmm… maybe that’s why it got the name Gesher Adam — the human bridge.) But as we know, Yaakov left behind small jugs that he went back for, which brings us to a Chanukah connection as well: The Kav Hayashar brings a tradition that Yaakov had in fact returned for the oil jugs in order to anoint his mizbeiach in Beit El. That jug of oil for which he was moser nefesh would eventually be the same jug of oil that his descendants would later find in the story of Chanukah their mesirus nefesh to fight against the Greeks.

It was there, on the other side of the river, that he met his existential challenge as he fought with the angel of Eisav all night long. He wins, of course, and walks away with the blessing and a name change, thus setting the precedent for all time — when Jews come into Eretz Yisrael, there’s always somebody at the border that will try to change your name.

Good Fences

From ancient history we move on to modern history, traveling all the way up to the northernmost point of Israel — the border city of Metula. Purchased by Baron Rothchild in 1896 in order to settle Jews in the north of Israel, the tiny town of a few hundred consisted mostly of religious Jews fleeing persecution from other countries who had come to Eretz Yisrael in the First Aliya. Although it was originally to be part of the British Mandate, the British handed it over to the French after World War I for a short period of time until it reverted to British control.

We are standing by what was known as the Good Fence, the border crossing with Lebanon, opened in 1976 and closed in 2000 after Israel’s withdrawal from Southern Lebanon. From the mid-‘70s until the first Lebanon War in 1982, this fence was an open border where thousands of Lebanese would cross into Israel to work, to shop, attend school, receive medical attention, and to visit relatives. In time though, with the wars and terror attacks and Israel ultimately leaving southern Lebanon, this area is now a closed military area.

The relations between the Jewish and Arab residents who had lived relatively peacefully under Ottoman control of the area fell apart in the chaos that followed World War I under the French and British control of the area. The British eventually instituted what was known as the “White Papers,” which were various limitations on the Jewish immigration to Israel. This was unacceptable to idealistic early Zionists who recognized that the founding of a Jewish State would require a Jewish populace to build, defend and establish it. And as Jews were suffering more and more persecution in the surrounding Arab countries, it was becoming critical to get them out. It was through this northern border that thousands of Jews were smuggled into Eretz Yisrael under the British mandate.

We have testimonies from some of those immigrants who describe their midnight runs on rainy nights through the hills and deserts of Lebanon and Turkey, enlisting Arab guides and bribing officers meant to be patrolling the border. In some cases these guides would turn on these refugees and ask for more money, stealing their life savings. Others describe the fear of being ambushed by Arab gangs or of being caught. They traveled days and months, hungry and tired, with their children on their backs. Arriving at the border, they had to cut through fences and crawl through the border gaps. The locals here in Metula and other neighboring Jewish settlements would take the refugees in their homes where they would care for them and then send them off to other parts of the country. It is estimated that tens of thousands smuggled themselves into Eretz Yisrael in the 25 years prior to 1948 through this northern passage. Today though, as we look at the huge border walls with electrical fences, sensors, and cameras posted every few feet, we’re happy to be on the right side of the border this time.

Land and See

We now move down the coast, to the western sea border of Eretz Yisrael, heading over to the British “illegal immigration” detention camp of Atlit on the Mediterranean Sea, just south of Haifa. If there is any place to appreciate the struggles and sacrifices Jews made to come to Eretz Yisrael in modern times, this is it. The detention camp, today a museum under the authority of the Ministry of Defense, has been preserved and reconstructed to give its visitors an appreciation of what those early immigrants went through to come here. The camp was established by the British to hold the Jews captured by the British patrol boats as they tried to sneak into Eretz Yisrael by sea. Over 10,000 Jews were held here in the periods before and after World War II — most of them Holocaust survivors or those who had fled or were smuggled out of Europe before, leaving their families and possessions behind. (The camp was closed in 1942, then reopened in 1945 with the wave of illegal immigration after the Holocaust.) The boat journey could take weeks, and sometimes months, and the conditions were horrible, with little food and cramped quarters — often the “passengers” were hidden with cargo, only to see daylight for an hour a day when allowed on deck and the coast was clear. The gates to Israel may have been closed, but nothing could stop the Jewish spirit from doing everything that it took to get here.

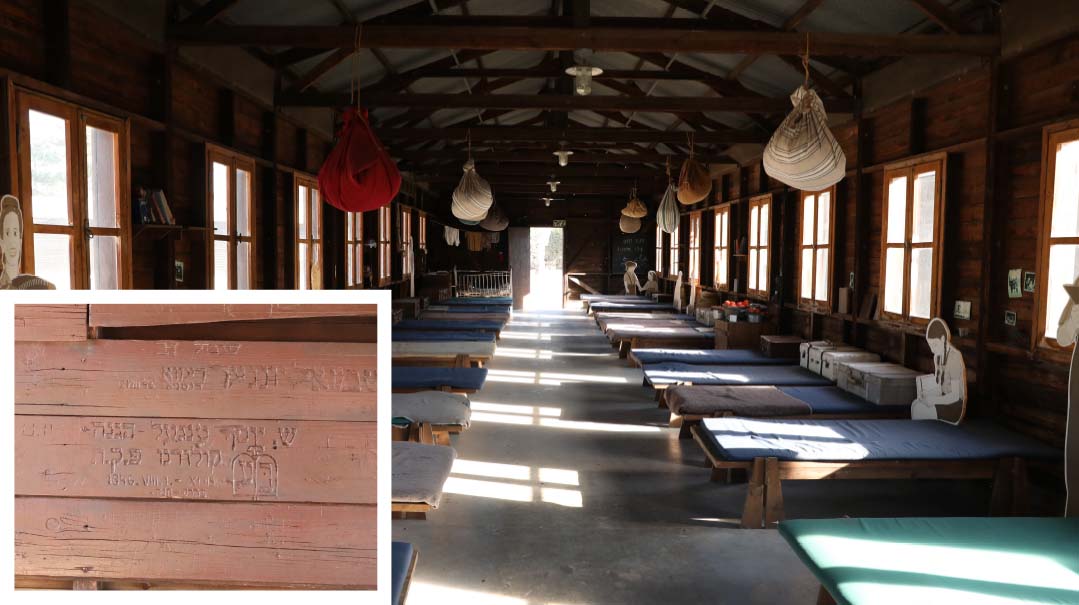

As we walk around we see a reconstructed model of the camp, which looks eerily like a tour of the concentration camps. The detainees arrived here on trains that ran next to the camps from the Haifa port, where their captured boats were docked. The refugees were greeted by armed British soldiers and fierce barking dogs, the men and women would be separated, and then be whisked away to large rooms where they were ordered to remove their clothing, which were placed in huge, noisy smokers that would fumigate them to remove any diseases. Many of the refugees had hidden in their clothing their last mementos or photographs from their homes and families, most of which were destroyed in this process, leaving them bereft of their only connection with what they had left behind.

The prisoners were sprayed with DDT, then made to enter large shower rooms, which was an unimaginable trauma for Jewish Holocaust survivors, some of whom had been in concentration camps where the “showers” meant instant death. Yet despite the hardships, these refugees were grateful that they’d been hauled up to shore, that they were here in Eretz Yisrael in the land that their ancestors, and their own perished families, had only dreamed of.

We walk from the showers to their barracks. Today they look quite roomy and comfortable, yet back then they were extremely cramped with over 30 prisoners per room. We read the names of some of the people who were here and cities they lived in, etched into the walls like graffiti. This was the prisoners’ way of notifying any of their surviving relatives who might also be detained here that they were indeed still alive. Atlit might have been a detention camp, but in all fairness, it was no concentration camp. The detainees had classes, they were taught the language, they rested and recovered, and were even visited by relatives. The religious detainees had their own barracks and even a makeshift shul and Torah.

It wasn’t exactly camp, however, and in October of 1945, the Palmach, under the director of a young officer named Yitzchak Rabin, raided the camp and released 208 detainees, leading them through the mountains and disbursing them in the local kibbutzim and settlements on Mt. Carmel. After that, the British began deporting immigrants to Cyprus internment camps instead, which operated from 1946 until the founding of the State and the exit of the British two years later.

From the barracks we follow the trail toward the sea, passing various displays of boats that had been used to smuggle Jews in. We pass an airplane too — the same craft that was used in 1947 to clandestinely smuggle in over 100 Iraqi Jews in “Operation Michaelberg” — named after the two American pilots who owned a commando transport plane and were hired by a secret branch of the Haganah (the precursor to the Mossad) for the mission. In the still of the night, the Jews, with only a few hours warning, were rushed to the end of the tarmac and shoved into the idling plane’s small cargo bay. The plane landed in a field in Yavne’el, illuminated by stacks of hay the farmers had set on fire to mark the landing, and which were quickly extinguished before the British caught on.

I Hope it’s Here

No tour of historic border entries to Eretz Yisrael would be complete without a visit to Rosh Hanikra, Israel’s northern border with Lebanon on the coastline. This was where the very first Ivri crossed into the Land. Heeding the call of lech lecha, Avraham Avinu and Sarah Imeinu leave behind the tremendous community of G-d-awarenss that they’d spent decades building in chutz la’aretz, and come to the Holy Land. The Yalkut Shemoni tells us that when Avraham was leaving Aram Naharyim and passed the city of Nachor on his route, he saw people eating and drinking and frolicking, and said “Halevai this is not the place Hashem is sending me.” When he came to the Sulam (ladder) of Tzur (the name given to the steep incline down the mountain from Lebanon to Israel, the border of Eretz Yisrael of the olei Bavel and from which point the specific agricultural halachos of Eretz Yisrael begin) and saw people working their fields diligently, he said “ and Hashem then told him, “L’zaracha etein es haaretz hazos.”

Rosh Hanikrah is part of a mountain range that is formed out of sandstone on top and whose base is made out of limestone. This unique combination of soft upper rock and a hard lower base led to the formation of the stunning natural grottos in the mountain. Josephus tells us that in the times of the Chasmonaim, Shimon HaMaccabi’s rule began from here all the way down to Egypt. Later on during the Roman period, the Amora Rabi Yaakov Bar Idi lived here and the scholars who were on their way to Bavel would stop by here. Upon reaching the border, though, some of those rabbis felt it was too much to leave Eretz Yisrael and turned around and went home. After all, who knew if they would merit to come back?

We take the famous cable car — the shortest and steepest in the world — down the mountain, where we can see the former tracks of the railroad blasted through the rocks to connect to the Cairo-Istanbul line that ran from Turkey down Lebanon all the way down to Egypt. This railroad was constructed by the British during World War II when they feared the Nazis would enter Eretz Yisrael from the south, and they needed a way to move troops and weapons rapidly down the coastline. The Nazis never came to Israel, but the railroad was indeed used, at least once: for the transport to Palestine of 222 Jews being held in Bergen Belsen who could prove British citizenship. They were released in 1944 by the Nazis in exchange for 300 German Templer Nazi sympathizers that the British wanted out of the country.

The railroad was ultimately blown up by the Haganah in the War of Independence to prevent Arabs from bringing in weapons from Lebanon, and it was also where the original armistice agreement at the conclusion of the war took place between the two countries — the border that’s still here today.

As we stand by the border, schmoozing with a chayal in a black velvet yarmulke who has put down his pocket Gemara to speak with us a bit about his service here, we stand in awe of all of the tribulations, sacrifices and challenges of Jews throughout the generations to get to Eretz Yisrael — passing through splitting seas and rivers, days and nights hiking and climbing through mountains and deserts, traveling on trains, planes, and boats, and facing fierce enemies and angels of Eisav and Yishmael. Hashem has performed nissim for us throughout the generations bayamim haheim, and may we soon see the ultimate Return bazeman hazeh!

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 888)

Oops! We could not locate your form.