Ferried to Freedom

| June 18, 2024Elderly Danish Jews relive the night they were rowed to safety

A narrow waterway between occupied Denmark and neutral Sweden was the escape route for 95 percent of Danish Jews. In that famed rescue mission aided by local authorities together with Danish underground resistance, 7,200 Jews were saved, and some of them are still around to share their memories of those frightening nights

AS Hitler’s Third Reich moved through the European continent, destroying countless Jewish communities, the Jews of Scandinavia were also in Nazi sights. In October 1942, the Gestapo rounded up all the Jews they could find in the tiny community of Oslo, Norway, and deported them to Auschwitz, where almost all of them were murdered.

But the fate of the Danish Jews was completely different.

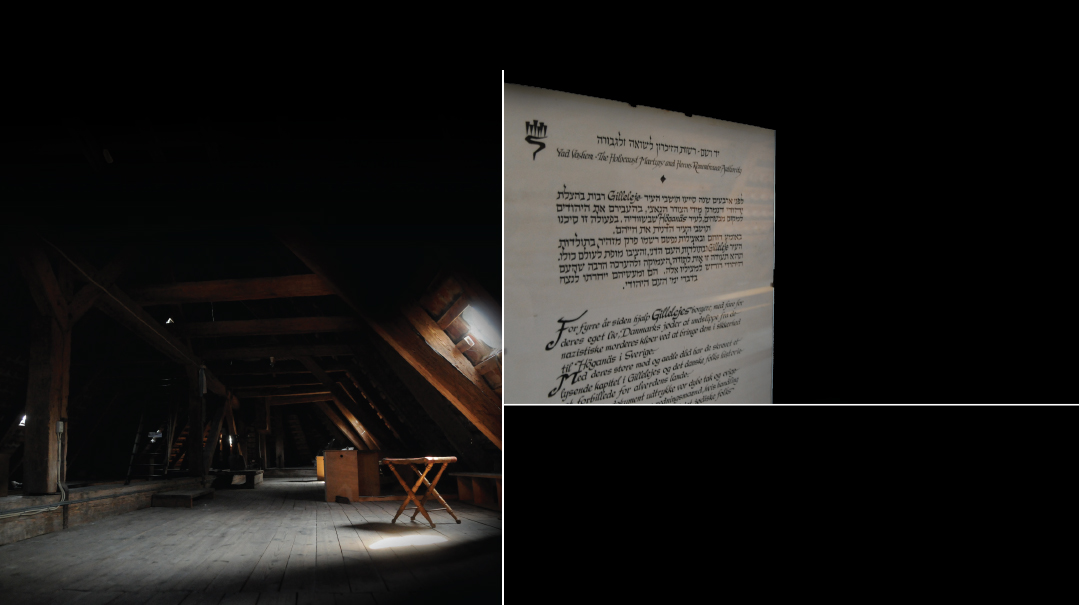

For the first three years of the German occupation, this 8,000-strong Jewish community remained untouched. In October 1943, when the Gestapo planned to round up Denmark’s Jews, a tip by a German diplomat in Copenhagen gave the Jews a window of escape: Over a period of two weeks, about 7,200 Jews and some 700 of their non-Jewish relatives, assisted by local authorities and the Danish underground resistance movement, were ferried by fishermen from the village of Gilleleje and others across several narrow waterways that separate Denmark from neutral Sweden. About 500 Jews were caught in the Nazi raids and deported to Theresienstadt, but most survived the two years of their incarceration.

Three escapees to neutral Sweden, just children at the time, share their journeys.

Henri [Chanoch] Nachman

The message reached us the day after Rosh Hashanah: “The Gestapo is rounding up Jews. Run”

O

ne of the first things I remember is hundreds of German troops marching along the main road in Aarhus, the city where we lived in Jutland, Denmark. I was playing outside, on the corner by the bakery, and my friends called me to get inside, out of the way, because I was a Jewish kid. The soldiers marched past. This was April 1940, when the Germans occupied Denmark, but they didn’t do anything to the Jews.

My father had come to Denmark in 1930 to join a group of chalutzim who were studying farming in the Jutland countryside in order to go to Palestine and make the desert bloom. He came from a very religious family in Gdansk [Danzig] where his father was a gabbai of the community, but he was the black sheep, a Zionist chalutz.

My mother’s family, meanwhile, were more socialist than religious, but they kept the chagim, and they hosted my father when he wanted to spend Rosh Hashanah and Pesach with a Jewish community. My parents married in February 1936, and I was born in Jutland. Although we, too, kept the Jewish holidays, I didn’t know very much about Judaism as a child.

By October 1943, I was six years old and just starting school. There was no synagogue in Aarhus, but my father used to go to blow shofar in the next town, which had a few Jewish families. The people around us more or less knew that we were Jewish, and some of the Jewish families in Jutland had friends in Copenhagen. The message reached us the day after Rosh Hashanah: “The Gestapo is rounding up Jews. Run.”

That day after Rosh Hashanah 1943 we went to the train station in Jutland and boarded a train to Copenhagen. We separated to avoid attracting attention. My parents and my baby brother got on near the front of the train, while the oldest daughter of our good Danish friends who lived in the apartment below us traveled with me and my sister at the back. You couldn’t take much along, either. It would have been far too obvious to take the train laden with suitcases. Even taking diapers for the baby was problematic.

My parents didn’t tell me much about what was going on at the time, but clearly, the underground resistance movement was helping us escape, because at Copenhagen’s main train station, someone waited for our family, and brought us to the assembly point at the city’s central hospital. Around 200 Jewish people were hidden in a big room under the hospital chapel.

The next night we were moved by taxi, or maybe they were private cars. I remember that another man sat in the front seat, and my parents and all three of us children were in the back seat. A head poked in: “Are you all one family?”

My father said “Yes, yes.”

I wanted to say no, but his hand covered my mouth. I fell asleep. We were driven through the dark, and suddenly I awoke. It was still dark, but I could see a farmhouse lit up on the coast, with the sea and a small harbor visible in the background.

We got out and waited, but then a voice said nervously, “German ship. Back into the cars.”

We got back into the cars and drove on to far south of Zealand (a region in Denmark). And then I don’t remember any more until, I was told, 20 hours later, when we came up from the hold of the boat into the light, at a safe Swedish port, and were welcomed by a Swedish policeman.

It turned out that our family was part of one of the biggest groups to be rescued. We’d boarded a boat and sailed for a long time, although everyone knew that Sweden is only two hours away from the coast of Denmark. The younger Jews on the boat got fed up and went up to see what was going on, and were stunned to see the sun rising on what they thought was the west — but it was on the right side of the boat! They realized that if the east was on the right, we were sailing south, toward Germany!

They discovered that our captain was drunk. He had been so nervous about his illegal cargo of Jews that he had been drinking to calm his nerves. After getting him out the way, they sailed the boat north again to Sweden.

We were one of the last boats of Jews to make the trip. My parents didn’t have the money which the boatman demanded, so they’d paid with their silver cups to be allowed to join.

In Sweden, we were taken to a mansion somewhere in the countryside. I remember the big rooms for the children, with five-tiered bunk beds, and that we played outside in the snow. About a month later, my parents were given an apartment in Malmö. I was seven, my sister was five, and the baby was one-and-a-half. But the escape had been too much for my mother; she became ill and was unable to cope with it all. We children were placed in care. My sister and I spent 20 months with Swedish Christian families in a town north of Gothenburg, while my baby brother was placed in Stockholm. We joined Swedish schools and learned the language. Our foster parents were very kind, and we kept up with them for years afterward. When my mother recovered, we rejoined my parents in Malmö.

The extended family was with us as well. In 1944 my grandfather, who had also lived with us in Jutland, died in Malmö. There were quite a lot of Danish-Swedish marriages during that time. My mother had four sisters, who all found Jewish Swedish boys and married in Sweden during the war, staying there afterward so our family became more Swedish than Danish. My parents returned to Denmark in 1945, though we settled in Copenhagen rather than Jutland. My mother’s brothers did the same, except one who, sadly, married a non-Jewish wife and went back to Jutland.

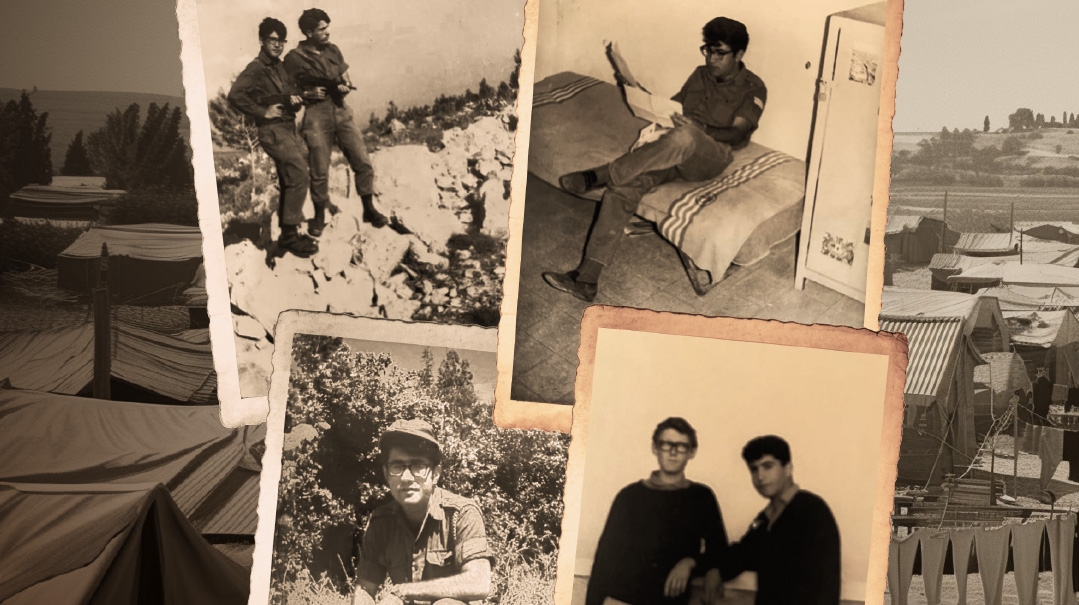

My father’s Zionist longing ran deep in our family, and my younger siblings all live in Israel. I spent a year in Jerusalem in 1956, training as a Bnei Akiva madrich. Nowadays, I serve as the gabbai in the Krystalgade synagogue, and my children and grandchildren live here in Copenhagen.

Margit (Rochel Lea) née Blackman

We didn’t know about the concentration camps at that time. We didn’t know where they were planning to deport the Jews to

I

was a pampered only child born in 1938. My mother was from Gothenburg, Sweden, and my father, Avrohom Blackman, was Danish. He was a businessman, owner of a men’s clothing business, and we lived in a beautiful apartment in Copenhagen. During the German occupation, my father took advantage of the wartime upheaval to go to the Swedish embassy and get himself Swedish identity papers.

My mother had a friend whose husband was a police sergeant. One night, I think it was on the third or fourth of October, that couple knocked on our door, and said, “Now, you need to escape.”

When you escape, you take nothing with you. There were 200 apartments in the complex, and everyone could look down and see us going, so we left with nothing. As was common in Denmark, a doctor lived in the apartment above the local pharmacy. He took care of us that night, when about 40 members of our extended family, including my grandparents, aunts and uncles, piled with us into his apartment.

The next morning, some men came to the door with instructions to help us get to safety. “You have to go to the hospital.” But for some reason, my mother refused to hide in the hospital, so we split up from the rest of the family. My father called a cab, which took us up North to Gilleleje, a fishing village.

The church in Gilleleje sheltered about 80 Jews that night. They hid in the attic, waiting for a chance to cross the sea to safety, but a young Danish woman informed on them, and in the morning, the Gestapo came. My parents and I were in the same church, but instead of climbing to the attic, we’d stayed down in the social hall. When the Gestapo came down the steps, with 86 Jews their new prisoners, we heard a woman’s voice saying, “There are also some Jewish people in there.” They opened the doors and found us in the social hall.

All the Jewish captives were brought down to the hall. I don’t remember this, but my mother told me that I cried because I was thirsty, and I was given some water with a Gestapo gun pointed at my back.

We didn’t know about the concentration camps at that time. We didn’t know where they were planning to deport the Jews to, but my father’s great fear emboldened him. He went up to the Danish collaborators who had joined the Germans, and told them firmly, “We don’t belong here! We are Swedish citizens!”

They looked at us with cruelty in their eyes, as if we were animals and not humans, but they accepted that claim. One of them tore a page out of a notebook, took a blue pencil, and wrote the date and the words, “Drei Juden” [Three Jews]. “You have twenty-four hours to get out of the country,” he said, giving the paper to my parents as a kind of safe pass.

We left the forlorn group — they would be deported to Theresienstadt and held there for over two years — and my father once again called a cab. Although there were ferries going directly to nearby Sweden, he was too afraid to travel openly. Instead, we went down south to a different coastal area and took a boat from there.

When we disembarked from the car, my father put me on his shoulders to walk through a forest. “If anyone asks you your name you say ‘Margit Rasmussen,’ not Blackman,” he instructed. We came to a fisherman’s house; the fellow had one earring and a red headscarf, and my parents paid him well to take us over the Oresund. It wasn’t a long journey, but we had to lie at the bottom of the boat.

The Swedish were wonderful. I remember their welcome. Our extended family also made it there to safety, and my father soon joined the Danish Brigade with the resistance workers.

Although my mother was Swedish, she was one of the first to say she wanted to go ‘home’ to Copenhagen when the war was over. We came back in 1945… to nothing. My grandfather knew a furniture businessman who was supposed to store our things, but he stole all of it instead. Thank G-d we had our lives, but we had nothing else.

Mrs. Mildred (Mina) Guttermann

I remember the Gestapo coming into our house, where my mother and I were alone. “You have ten minutes to leave this house,” they declared

I

was born in Oslo in 1932, to my father, Alf Levin, a Norwegian Jew, and my mother, who was born in Sweden. Their families had emigrated from Russia to Scandinavia one or two generations earlier. Our community was small, but we had an active shul and some Jewish infrastructure.

I was eight years old when the Germans invaded, despite the fact that Norway had declared itself a neutral country. Germany did this for strategic reasons, seeking access to Norwegian seaports and naval bases from which they could strike the British, and because they wanted to protect the supply of iron ore which they were importing from Sweden. In their racial ideology, they actually believed that Norwegians were racially superior to Germans. But the Jews, of course, had to be gotten rid of.

In Norway, they rounded up the men first, helped by Norwegian plainclothes policemen. The Donau, a German ship moored in Oslofjord, Oslo’s harbor, carried off 532 Jews, who arrived in Auschwitz five days later, on December 1, 1942. My father and his brother managed to disappear and went into hiding, evading arrest. They were smuggled to Sweden in a cupboard that was secured on top of a truck, with holes for them to breathe. A German patrol stopped the truck. “What is in that cupboard?”

“Glassware going to Sweden,” said the driver. And they were waved through.

I remember the Gestapo coming into our house, where my mother and I were alone. “You have ten minutes to leave this house,” they declared.

We did. Our non-Jewish neighbors took us into their home across the street, and within ten minutes, the Germans came back, and our door was marked with the seal of the Gestapo.

We were so lucky — although our home was confiscated, somehow, we were not rounded up. Since the Gestapo took the men first, the women and children had some warning, and a bit of time to flee. We were at that neighbor’s house when one of the resistance organizations got involved. They knew we had to get to Sweden.

I remember traveling in a bus out of Oslo and up to the mountains, where we then walked for ten hours to cross the border into Sweden. There were only women and children, and a helper from the Norwegian resistance. I was given a relaxant so I shouldn’t cry, but I still had to walk.

After we made our way across the border, we were taken on a train to Stockholm, where we reunited with my father. The next two years were spent in a small flat in a Swedish town. We had no idea what had happened to our extended family.

During the war, my parents sent parcels from neutral Sweden to our old neighbors in occupied Norway. In 1945, my father was the first to go back to Oslo. He knocked on the door of our home. It was answered by German officers, who had requisitioned the house.

“My family are coming back here in two weeks,” my father told them.

“That is too quick,” the Germans replied.

“We were given ten minutes to get out,” he said.

When we came back, they were gone, but they had emptied the house of all our furniture and belongings. The house was decorated with Norwegian flags by our neighbors, who had heard we were returning.

My father had to start a business from scratch again, and I, at age 11, had to learn Norwegian again, because I’d forgotten the language. But that was nothing — we were the lucky ones. Of the 532 members of our family and community on that German boat, only nine Norwegian Jews survived Auschwitz and came back to Oslo. My mother’s younger brother, who had been arrested in his school as an 18-year-old, came back, but her older brother didn’t. My father’s brothers had been killed in Buchenwald. I had my cousins back, but I was the only one who had two parents. All of them had lost a parent.

Life in Norway wasn’t easy for my parents, but they stayed there. Some years later, I went to a summer camp operated by the Scandinavian Jewish Youth Club. Norway, Denmark, and Sweden have a lot of similarities in culture, although the languages are different. I was standing on the boat with my cousins, when my husband, Avrohom (Erik) Guttermann, saw me, and that was that. I married him in 1953. Avrohom was from a nice big Jewish family here in Copenhagen, and when I moved from to Copenhagen from Oslo, I felt like I had come to Heaven.

We had a larger Jewish community here, and my father-in-law, Herman Guttermann was one of the founders of Machsike Hadas, Denmark’s frum shul, which my husband later served as president. There still weren’t so many Orthodox kids around, though, and we had to be strong. We had to keep our children at home, we couldn’t just follow what everyone else was doing, and we could not allow them to join youth groups where we knew there was mingling, because sadly, intermarriage rates are very high here. We made sure to send them to yeshivos and seminaries in Jerusalem and in Lucerne.

My husband had a lot of ideas. He supported a kollel in Copenhagen for some time, and he opened a shul and kosher hotel in Hornbaek, on the Danish coast, hoping to attract Jewish tourists. One day in the 1990s he came home and said to me, “You are going to have twenty more kids.” And soon there was a new yeshivah in town, for Russian teenagers who wanted to catch up and become yeshivah bochurim. We had the boys almost every Shabbos over the next five years. They had a good time in Copenhagen and we watched many of them go on to learn in wonderful yeshivos in Eretz Yisrael and America.

Some of my children lived here for a while after they married, but only one lives in Copenhagen today. The community has declined, and there are not many Orthodox Jews left. Remarkably, my oldest daughter married a man from a Norwegian Jewish family who we knew before the war. But today they live in New York.

Four summers ago, I took my family, the children and grandchildren and great grandchildren, bli ayin hara, back to Norway, so they could see where we lived and visit my parents’ kevarim. Nothing remains there.

But baruch Hashem, a lot remains of us.

Riki Goldstein is the author of the upcoming book Escape from Denmark, by Menucha Publishers.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1016)

Oops! We could not locate your form.