Lost and Found

| June 13, 2023It got darker as I trudged along, trying not to lose my way, never forgetting for an instant the verse “ein oid milvado”

As told to Raizel Rosenberg

I’M

a chassidishe kollel yungerman (can I still call myself that if I’m pushing forty?) who has been blessed in so many ways. I still get satisfaction from sitting and learning all day, I have a caring wife who works hard to support my learning and tend to our three wonderful children, kein ayin hara.

I couldn’t ask Hashem for anything more. But I don’t know if I would ever have properly appreciated the gifts He’s given me until He took me out of my comfort zone, and arranged for me to help a mysterious stranger I never even met. Here’s how it happened.

My oldest son, Sruly, is a brilliant yeshivah bochur, with amazing middos — and everything else proud parents could hope for. But last year, Sruly contracted a worrisome case of Covid. His illness stretched on for days, then weeks, then months. In our rising panic, we did everything — visited the best doctors in the field, obtained lists of prescriptions and natural remedies, fed him nutritious food, spending hundreds, maybe thousands of dollars, all to no avail. Sruly was only getting weaker and weaker.

Then we heard about a specialist named Dr. Klatzkin in a far-off city who dealt specifically with cases like ours. What would parents not do for their child? We booked plane tickets and were on our way.

As soon as we arrived, we realized that the apartment we had taken to be near the doctor was in an area without a single Jew in sight. Here I was, fully attired in chassidic garb, long peyos and beard, long jacket and gartel. I had never really had much contact with anyone besides chassidim, Yiddish is my first language, and I was at a loss as to how to carry on a conversation in English.

But my biggest concern was getting a minyan for Shacharis, Minchah, and Maariv. I was beginning to think there was not even a minyan of Yidden in this whole town.

After many unsuccessful phone calls, I eventually reached an askan who advised me to call Chabad and have them refer me to the closest shul. I was so grateful when a friendly voice answered there and offered to come pick me up and drive me to a minyan, about half an hour away by car.

He was true to his word. I was so happy when I walked into the shul to daven Minchah. It was the first time I had seen Jewish faces in four days. I had certainly missed the kosher stores and pizza shops of my neighborhood back home, but most of all I had missed my Jewish brothers.

The people in this shul weren’t like me at all — dressing, speaking, and behaving completely differently. But I felt such an enormous rush of love for each of them. I wanted to hug each of these Jews and tell him how precious he was.

I settled into a routine in this new place, davening three times a day and taking care of my son, accompanying him and my wife to doctor’s appointments. I even found a car service that would take me to shul.

Then, suddenly, it was Friday. It was time to worry about Shabbos.

I didn’t want to leave my wife and son for even one day, but I also felt I had to go to shul. Then again, it was way too far to walk.

And then we got a phone call.

“Hello, this is Mr. Schreiber,” said the voice on the other end. “I got your phone number from the rabbi. I’d like to invite you and your wife and son for Shabbos, so you can join us for davening.”

This kind invitation prompted a flurry of discussion between me and my wife. She suggested that I go by myself. I pleaded with her to join me; I didn’t want her and Sruly to be alone for Shabbos. But she insisted she wanted to stay behind with our son. In retrospect, that was clearly her binah yeseirah directing her actions.

So it was that I found myself with a car service, bringing all my Shabbos clothes in a small suitcase and my shtreimel, along with the food my wife had kindly prepared for me.

The driver was very nice. He brought me to the address Mr. Schreiber had given me; I paid my fare, along with a tip, unloaded my belongings from the trunk, and waved goodbye to him.

I’m on my own now, I thought. Little did I know how alone I really was.

I wheeled my suitcase to the door of the home and rang the bell. No answer. I knocked and rang again, and again. Nothing. Well, maybe in this state people just leave their front doors open, like in the bungalow colonies of my youth.

I tried the door. It was tightly locked. I looked for a back door. There was none. No side door, either.

I took out my cell phone and called Mr. Schreiber. Several times. No answer.

I decided I would walk straight to the shul. It couldn’t be too far, I reasoned, and if I had to, I could sleep in the shul. I picked up my bags and started off, but I had no idea which direction to go.

I met a man in the street who appeared to be friendly.

“Excuse me,” I asked him. “Would you happen to know the way to the shul? I mean, synagogue?”

He looked at me as if I just stepped off a flying saucer. I simply walked away.

After asking different people, I finally got some information, but the directions were very confusing. The streets here were not laid out in a grid, like the ones in my neighborhood. There were no sidewalks and no curbs, and the street names changed every few blocks. At every corner, a new street sign came up. I was utterly baffled. I followed the directions to the best of my ability, but I seemed to be walking around in circles.

Pretty soon I wandered into a different neighborhood. Here, there were sidewalks, but they were broken. The people didn’t speak any English, and they didn’t look like people I would approach with questions. We regarded each other with mutual suspicion.

Suddenly, a huge German shepherd ran up to me, barking furiously. I had never had anything to do with dogs, I didn’t know what to do. And then I saw him — a husky six-footer sitting on a beach chair by his house, looking on amused. I guess to him it looked kind of funny — a Hasidic Jew in a strange neighborhood being harassed by a big black dog. I was paralyzed with fear. Even had I tried to flee, I wouldn’t have known where to go.

The man said in a soft, low voice, “Blackie, don’t bother him.”

“Blackie,” of course, ignored him.

I began imploring loudly, “Where is the synagogue?”

At this, he got up and started walking toward me. Now I was really frightened. There was no way I could fend off both this strapping, menacing-looking man and the angry German shepherd. “Ein oid milvado,” I kept repeating to myself, over and over.

Everything seemed to move in slow motion as he drew up to me. I had a metallic taste in my mouth.

“What do you want?!” he shouted.

“Do you know where the shul is?” I asked in a quivering voice. The English word escaped me, but suddenly I remembered it. “Do you know where the synagogue is?”

He pulled out a smartphone, and asked me how to spell “synagogue.” That was another comedy of errors, but somehow, he finally found it.

He showed me the directions on his screen, very clearly. I thanked him profusely. Actually, Blackie and the man and his phone were the ones who saved me.

As I set off in the direction he showed me, each new block was worse than the one before it, but at least now I knew the way. “Ein oid milvado,” I kept repeating to myself, every time I passed an unsavory character.

I hurried on and glanced at my watch. It was almost Shabbos! I could see I wasn’t going to make it to the shul in time, and I had to assume there was no eiruv. I had to find a place to squirrel away my suitcase, hat, jacket, money, cell phone, and the delicious food my wife had lovingly prepared.

I spied out an inconspicuous tree and unobtrusively placed my belongings behind it, covered everything generously with leaves. Meanwhile, I donned my beketshe and shtreimel. And then I was on my way.

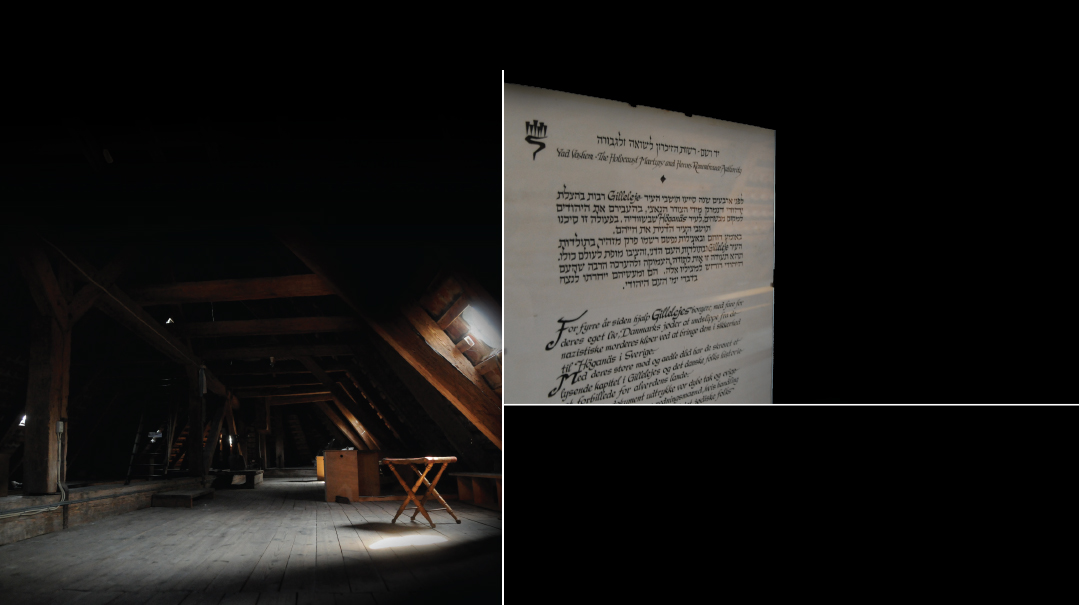

It got darker as I trudged along, trying not to lose my way, never forgetting for an instant the verse “ein oid milvado.” And then, finally, I saw a building emblazoned with Hebrew words. Here at last, I thought.

I walked up to the door of the shul and pulled the handle. It was locked. I banged on the door loudly, several times. Nobody answered. The lights were also out.

They must have davened early. They probably all went home. So this is what it feels like to be homeless, I pondered.

I sat down atop an old wooden box and said, “Hashem, I am now away from my family, with no friends, no place to sleep, and no place to eat. I am so hungry. Please help me.”

Suddenly, the door of the shul opened. A man came out, carrying a broom and a shovel. He saw me. He looked like all the homeless people I had seen on my way there.

He did not know a word of English. I pointed to the door and motioned to him that I wanted to go inside, and that I needed a place to sleep. He was suspicious. I pointed to my beard and my peyos to indicate that I was Jewish. He shrugged and seemed satisfied by that.

I followed him up the steps into the shul. He showed me to a small room behind the ezras nashim. I took off my shtreimel and sat on a bench, and thanked Hashem that I was indoors and safe. But sleep eluded me. I tossed and turned most of the night.

I guess I must have fallen asleep around dawn. I awoke to a bright sunny sky. I made my way down to the shul and was disappointed to find no one there. I was the only one in the entire building. When I found a wall clock, I was shocked to learn it was already two in the afternoon! I had missed the entire davening. My sadness gradually gave way to a gnawing hunger. I had not eaten for many hours.

With no choice, I davened alone. Afterwards, I noticed some leftover cake and some grape juice. I made Kiddush and ate. Then I took a sefer and started learning. That, at least, I could do. I silently thanked Hashem for that.

I was concentrating very hard on a pasuk when I heard the men entering for Minchah. They were all happy to find me there, and they honored me with an aliyah at Minchah. In return, I promised them a chassidishe Shalosh Seudos.

I was so happy at finally being able to eat a normal meal that I started to sing. I just couldn’t stop. I sang every song I knew. Wonder of wonders, the men started to join in, some even singing in the chassidishe style — first three, then five, until the entire congregation was singing.

We could have gone on like that all night, but finally, it was time to bentsh, daven Maariv, and make Havdalah.

One of the congregants, who introduced himself as Mr. Schwartz, offered me a ride home. Everyone stood up as I left and gave me a standing ovation. I bade them a fond farewell and was on my way.

As we got into the car, Mr. Schwartz asked me to show him where I had stashed my belongings on Erev Shabbos. I remembered the exact spot and navigated him to it.

“Do you mean to tell me that you walked through this neighborhood?” he asked in wonder.

“Yes,” I replied, “why?”

“This is the worst place to walk. You experienced a real miracle. You’re lucky to be alive!” He laughed. “I hate to tell you this, but don’t be surprised if you never find your things again. In this neighborhood, I don’t give it a chance. By the way, did you have money?”

“Yes” I answered.

“How much?”

“About $200.”

“You might find your clothing, but the money, for sure not.”

I shrugged. “We’ll see.”

He handed me a flashlight as I got out of the car. My heart beat rapidly as I walked up to the tree. I quickly found my jacket and checked the pocket — the money was still there, completely intact, just as I had left it, as was my cell phone. (There was a missed call from Mr. Schreiber. It turned out he had made early Shabbos and hadn’t received my calls. He felt terrible and apologized profusely.)

I brought everything into the car.

“The money was there?” Mr. Schwartz asked in astonishment.

“Yes, the money was there. But other things were missing.”

“Really? What?”

“My hat was missing,” I said. “And my shtreimel case was open. And something else was missing.”

“What was that?” Mr. Schwartz asked.

“I found an empty food container and a fork on the ground. Whoever it was obviously enjoyed my Shabbos fish, and I also found a small piece of leftover challah.”

Mr. Schwartz threw his head back and laughed. I laughed too, happy that this story had a happy ending. But it also left me with — zei mir moichel — food for thought.

Perhaps this man who came across my belongings was Jewish? Maybe he asked Hashem to send him a Shabbos meal. Maybe he needed a hat because he hadn’t made Kiddush in who-knows-how-many years. Maybe he remembered his mother serving fish for Shabbos?

Could it be he didn’t take the money because he didn’t want to touch muktzeh on Shabbos?

We’ll never know. But I do know now that every Yid is like a brother.

Soon after this story happened, we found a specialist of the same type as Dr. Klatzkin very close to our home. Our son Sruly has been recovering slowly, and we daven that he should have a refuah sheleimah.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 965)

Oops! We could not locate your form.