Draw Your Dreams

“I knew art was starting to heal me, that the real me — unafraid of expression, of judgment, of being misunderstood — was emerging”

Photos: Naftoli Goldgrab

The dream story begins with Moshe Shain’s grandparents.

His grandfather, Shmuel Levi Yitzchak Wadawski, was a chassid of the previous Skulener Rebbe, Reb Leizer Zusia; in later years he found his way to Chabad. He passed away when Moshe was young, but his grandmother, who lived for 16 more years, was an active part of the Shain family’s life growing up who visited their home often. She was fun-loving, on the ball, even active on the family chat.

In 2000, when Moshe was 11 years old, his grandmother was hospitalized for a minor procedure. She was recovering, she was fine — and then a message came the next morning: BDE Bobby passed away.

“We couldn’t wrap our heads around it,” Moshe, now 35, remembers. “She’d just texted a message seven hours before.”

When her second yahrtzeit loomed, Bobby’s children decided to hold a hachnassas sefer Torah in their parents’ memories, whose yahrtzeits fell out two days apart during the Aseres Yemei Teshuvah. Bobby had always wanted to write a sefer Torah in her husband’s memory, but she never got to it due to lack of money and energy.

Moshe wasn’t very involved in the arrangements. Of course, he and his wife gave some money and planned to participate — it was scheduled for a Sunday when the kids were off — but he wasn’t very into it.

Then, in the early Sunday morning hours, Moshe had an ethereal dream.

To understand that dream, we need to go back a couple of decades, to when Moshe was just ten years old.

IT

was right after the birth of his youngest brother. The Shain kids were farmed out, and his six-year-old sister Shiffy was at a cousin. Suddenly, a fire broke out in the cousin’s home. Panicked and rushing to escape, Shiffy broke her foot, and in those extra moments she waited to be lifted to the window to safety, she suffered severe smoke inhalation.

Shiffy was hospitalized even as the bris for the new Shain baby was held in their Monsey home. Moshe’s brother was named Refael; amid the simchah, there was fervent hope and prayer for a refuah sheleimah. But it wasn’t meant to be. A few days after the bris, six-year-old Shiffy passed away.

To her older brother, the death of his playful little sister was a violent shock, a slap in the face.

“I loved Shiffy,” Moshe says simply. “I used to play with her all the time, preferring her company to that of the brother between us. And then she was gone, with no warning.”

Moshe and his siblings were lost, floundering in emotions that were far too big for them: grief, loss, fear, guilt.

“No one even told us outright,” Moshe remembers. “My mother was postpartum, my father devastated. It just wasn’t spoken about.”

They couldn’t even cry; there was no one to cry to.

“My parents had a new baby, and they were in their own bubble of pain,” Moshe says. “No one else knew what to say. There were no organizations back then to deal with children who’d been touched by tragedy.”

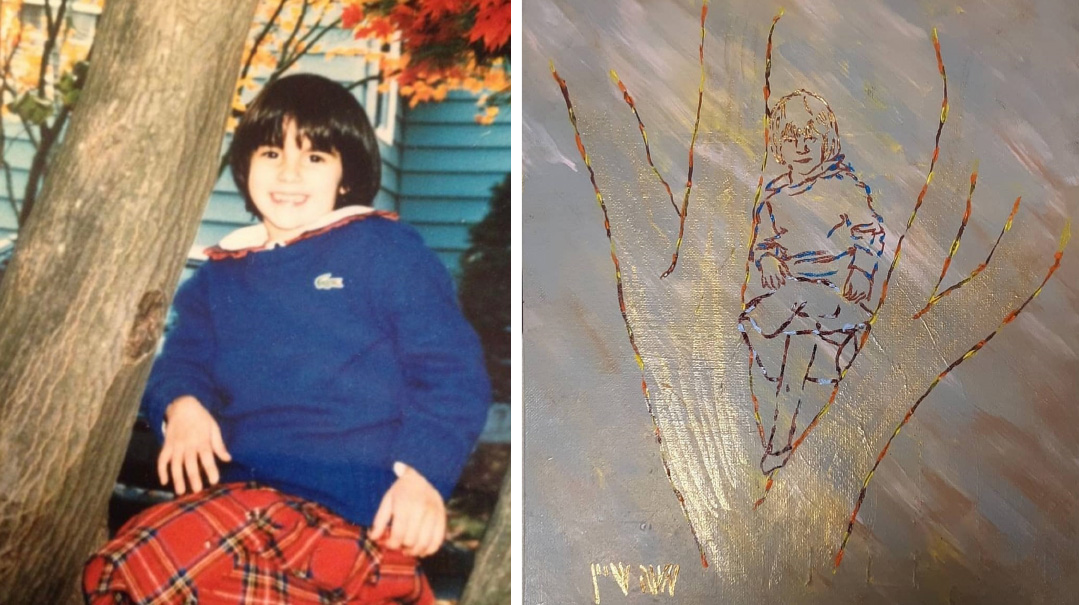

This photo of Moshe’s little sister Shiffy a”h served as the inspiration for the contour-style portrait he created of her. In the painting, Shiffy is behind a thin haze separating This World and The World to Come

T

he aftermath of Shiffy’s petirah was especially difficult for Moshe, a gentle, sensitive soul. As a young child in cheder and later in yeshivah, Moshe had questions no one could answer, as well as a different understanding of the learning. He remembers creative insights into Torah learning that no one else appreciated. For example, he says that while others took the pasuk “uvnei Korach lo meisu— Korach’s sons did not die” — at face value, he thought that bnei Korach could refer to the middos of Korach’s sons — jealousy and machlokes — which haven’t died, so to speak, and are still very much around today.

“I felt like the things that bugged me in learning were different from other people’s, like maybe my whole approach to learning was strange and unusual, which reflected back on me,” he says.

By the time he went to yeshivah in Israel, Moshe was disillusioned.

“I was a hardened young man, had been around the block a time or two,” he says, remembering how he went through the motions but wasn’t inspired much about anything.

Rabbi Avraham Yehoshua Heshel Bleich, the rosh yeshivah of Yeshivas Tiferes Avraham in Kiryat Sefer, took in the struggling 16-year-old.

“It was probably against his better judgment,” Moshe says. “I was tough, far from the menschlichkeit he embodied. I was acting in a way I shouldn’t, but my feelings were dead. And he was there for me, teenage angst and all, to support me emotionally and in learning. He set me straight.”

After almost three years in Rabbi Bleich’s yeshivah, Moshe returned to the US. He got married shortly thereafter, and the young couple settled in Brooklyn, where Moshe was learning. They soon celebrated the birth of their first child, after which Moshe starting working as a government contractor.

Moshe had harbored artistic and creative inclinations for a while, but art wasn’t encouraged or enabled in the chassidish cheder and yeshivah system; it just wasn’t in the lifestyle. Then in 2015, Moshe and his wife took a trip to Israel. It was a breather, an opening, and he decided he wanted to give art a real shot.

His wife ordered a whole bunch of supplies on Amazon. At first, Moshe just took pencil to paper and started to draw. Later, he tried out paints, mainly acrylics or spray paint on canvas or wood, all at his dining room table.

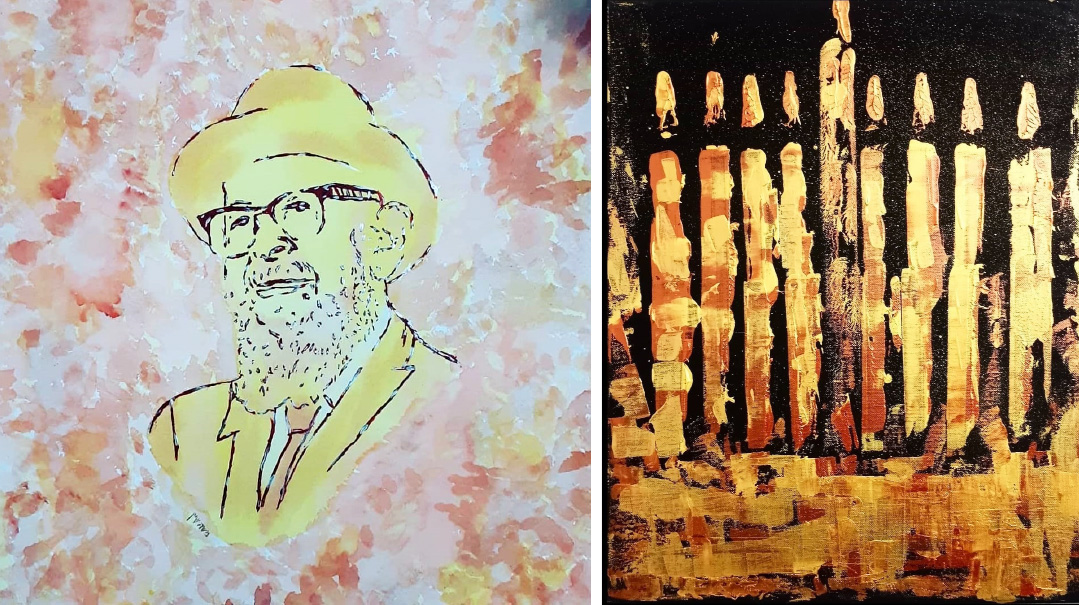

One of his first pieces was a painting of Rabbi Avigdor Miller, Rabbi Bleich’s rebbi.

“The menschlichkeit that characterizes Rabbi Bleich comes from a deep internalization of the teachings of Rabbi Miller,” Moshe says. “He’s a true talmid.”

At the time, even though it had been almost ten years since he left yeshivah, he’d remained close to Rabbi Bleich. Gifting Rabbi Bleich with this Rabbi Miller painting, a piece of his heart, meant a lot to him.

Rabbi Bleich, now a rav and therapist in Detroit, Michigan, called Moshe to thank him. He told Moshe about a client he’d worked with who was very broken and had found art on her journey to healing.

“I’ve seen what art and expression can do — I think it can be a part of your story, too,” Rabbi Bleich said.

That conversation was Moshe’s turning point. He decided he would explore his talent, no matter what it took — and ideas flew as he started to respond to the artist inside. Pictures of Shabbos, Yom Tov, davening, learning, faith. Portraits in a distinctive outline style, riots of color, abstract shapes and forms that are open to interpretation.

“I knew art was starting to heal me, that the real me — unafraid of expression, of judgment, of being misunderstood — was emerging. I have a hard time explaining things and expressing myself verbally, because I lack confidence. But I found I could communicate through art,” Moshe says of his new outlet. “It just tamed me.”

Moshe continued to paint, and in the eight years since then, he has created almost 100 pieces of artwork, each with a story, each one straight from the soul.

“My art always starts with a feeling: happy, upset, angry, uncomfortable,” Moshe explains. “I sit with the feeling, think about it, what’s underlying it, until an image surfaces.”

Once that happens, it can take Moshe anywhere from a few hours to several weeks to get that image onto canvas or wood.

Moshe’s art leans toward the abstract. Some prefer precise, realistic representations, which take talent, but to him, art is more than that: it’s your imagination, your heart, the way you think out of the box.

“There’s talent and then there’s art,” Moshe says. “It takes talent to reproduce something beautiful. Art is the creation of something new.”

When Moshe started painting, it was just for self-expression. But after a while, his work started getting noticed on social media. Later, it would even be featured in several galleries.

The responses from family, community, and beyond have been varied, but there are some who really get it, who appreciate his originality, his sincerity, and the heart and thought in every painting — and this audience requests custom commissions. Moshe’s main source of income is still his government contract work, but before that — and beyond that — he’s an artist.

Spiritually, Moshe associates his art with his personal growth; he’s not an actual baal teshuvah, but “Who that’s ‘real’ isn’t?” he likes to say.

Moshe’s connection with his deceased sister Shiffy has run deep all these years. Despite some misgivings, he and his wife were the first in the family to name for her, and he has visited her kever often. But he was busy with his family, his work, and his art, and Shiffy wasn’t always at the forefront of his mind.

Golden Touch

In 2021, on one of the nights before Chanukah, Moshe and his family were getting into the spirit, buying oil, candles, and new menorahs for the kids.

“The excitement, the warmth, I felt it all, and I had this sense that I wanted to create a menorah out of gold,” he remembers.

Moshe put a coat of matte black on canvas and then applied different shades of gold and copper in broad strokes.

“Lustrous gold on black, light chasing dark, it’s one of my favorites,” he says of this celebration of contentment.

D

uring Aseres Yemei Teshuvah in 2018, more than two decades after Shiffy’s passing, she appeared to Moshe in a dream as Sunday — the day of the hachnassas sefer Torah in memory of their grandparents — dawned.

“I recognized her face — I haven’t forgotten how she looked — even though she seemed to be about 16 in the dream,” Moshe says. “She was much taller than I remembered, wearing a shimmering gown of navy blue.”

Shiffy was mingling in a crowd, a cadre of people standing about, as though at a simchah. Moshe watched as she wove her way through the crowd and stopped when she met a man: “My uncle Moishy. Our mother’s brother. I heard her say two words to him: ‘Thank you.’ ”

Moshe awoke with a start. The image of Shiffy was still superimposed on his eyelids, her features as familiar as if decades hadn’t passed. He exhaled and made his way to Shacharis, still seeing her every time he blinked.

Should I tell Mommy? Or Uncle Moishy? Nah, it’s just a dream. I’ll tell Mommy at a more opportune time, better not to bring up something painful today.

But later that morning, Moshe was waiting for his kids to get ready for the hachnassas sefer Torah, and he went online.

That morning, he saw his younger brother and two aunts were online at the same time. Why not? Moshe decided, and he found himself talking about the dream.

OMG. I’m telling Mommy, his brother typed as Moshe recorded live.

Moments later, Moshe got a frantic call from his mother asking for more details. Soon after, she arrived in Crown Heights for the hachnassas sefer Torah. She related her son Moshe’s dream to her brother Moishy, whose face paled.

“What?” she demanded.

“Wait and you’ll see,” was all he said.

Moshe’s mother was perplexed, but a few minutes later, when they put the new sefer Torah onto the table, Moishy showed her the atzei chayim, the rounded pieces at the top of the Torah holders. They were engraved with the names of two grandchildren who had passed away very young.

“My mother saw the name Shifra Fraida,” Moshe relates. “She started shaking.”

Only two people had known about the names on the atzei chayim: Moishy and another sister. They hadn’t been sure about inscribing them there; after all, the Torah was in memory of their parents, not these grandchildren. But they’d had a gut feeling that this was fitting, and they went ahead with it.

“And my little sister Shiffy had come to me to tell them that it was,” Moshe says.

His mother’s siblings, who’d heard the dream before they saw the engraved names, were dumbfounded. Some of them hadn’t been so enthusiastic about the hachnassas sefer Torah, the money, the time, the energy — does it really make a different to anyone’s neshamah? they wondered.

That morning, they had their answer.

“When I mentioned the dream to my rebbi, Rabbi Bleich, he said, ‘I know why she came to you,’ ” says Moshe, who for many years had been plagued by a sense of culpability for Shiffy’s passing. “She just wanted to tell you it’s okay, she’s okay there, that you can move on and know it’s not on you.’ ”

A little while later, Moshe’s oldest sister asked him to produce a painting for her — of their sister Shiffy. It would be his most meaningful commission.

“I sat in front of the canvas, and I was ten years old again,” Moshe says. “The pain, the brokenness, the guilt, the loneliness, the shutdown — everything besides release.”

It took Moshe two weeks to finally get Shiffy’s face on the canvas.

“Her innocent smile made my heart stop… and the tears started flowing, raining.”

It was the first time Moshe was able to cry for Shiffy since she’d passed away.

Feelings that had been numb as ice were returning; the pain that made Moshe who he is, that became his story for better and for worse, was finally being channeled.

From the Ashes

One time, Moshe decided to create a piece about Shabbos. He started with a pale gray, silvery background. He painted the woman bentshing licht, contour-style, and last he put the Shabbos candles in.

The next morning, Moshe found a hole in the canvas; one of his kids had pierced it with a scissors. He was understandably upset, but he was pragmatic about it, patching it up with a needle and thread.

“What to do? What did I want to show here?” he remembers. “That the light of Shabbos covers and obliterates darkness and pain — so I’d put in more light. And in the spot where it was ripped I painted another flame, so I now have flames falling and flying in the whole painting.”

Outline Alone

Many of Moshe’s portraits are contour art, a style that focuses on outline alone but still maintains a strong resemblance to the subject. The first time he tried it, by chance, he fell in love with the concept, marveling at how much could be expressed by simple outlines. Only afterward did he discover that this is a recognized portrait style.

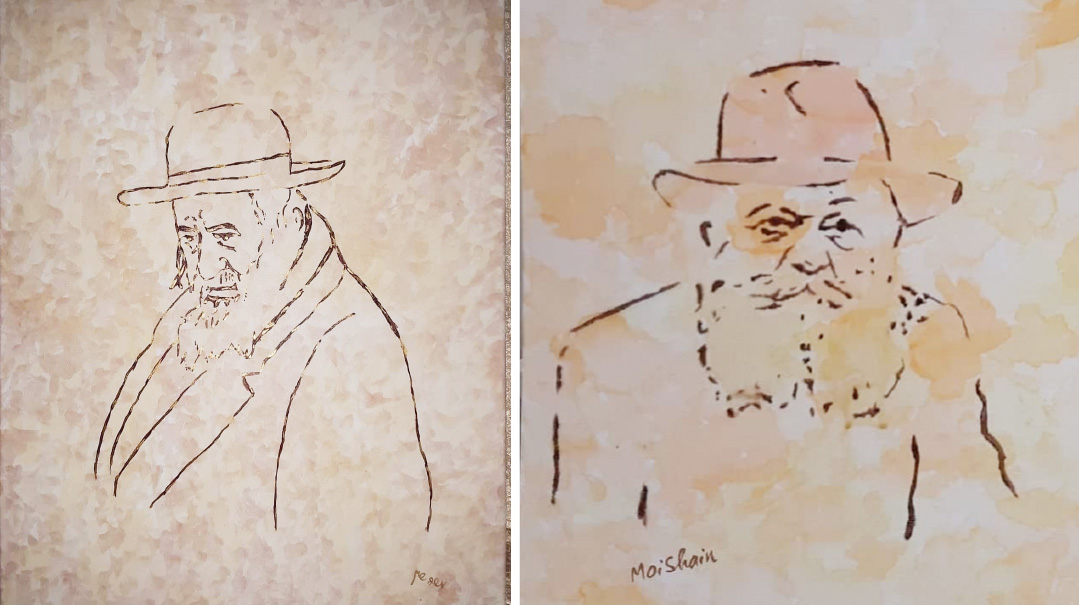

Reb Shayale

This portrait of Reb Shayale of Kerestir is precise and minimalist, in soft natural tones, with a personal story beneath it:

On his way to Israel for yeshivah, Moshe and some friends stopped in Hungary for several days. They didn’t have much money, and the bochurim just roamed about.

“We slept in hotel lobbies, didn’t eat much,” Moshe says.

They even spent one night in a field in Nyirtass, a Hungarian village near Satmar.

Eventually they ended up in Reb Shayale’s hoiz in Kerestir. It was the first place they found refuge and good, plentiful food.

“Reb Shayale’s spiritual energy never died, his people kept the place going with all that was important to him in his lifetime — generosity, feeding Yidden,” Moshe recalls gratefully.

A decade and a half later, Moshe had the opportunity to recreate Reb Shayale’s big-hearted countenance. He used shining colors, vivid golds in the contour, acknowledging the chesed he had experienced so long ago. The original hangs now in the home of one of Reb Shayale’s descendants — kindness repaid, light returning to its source.

The Lubavitch Rebbe

When it comes to outlines, the eyes and mouth are the most important to get right.

“You wouldn’t think the mouth is so important, but it conveys so much: emotion, attitude and personality,” he explains — “and the mustache,” too, he amends laughingly.

“My first outline piece was of the Lubavitch Rebbe, just eyes, nose, mustache. I nailed it, even extremely minimalistically, just by getting those right.”

There was the time someone wanted Moshe to produce a portrait of his mother and grandmother, who’d both passed away in the same year, and Moshe wasn’t happy with the result, because one of the mouths just didn’t come out well, and he had to let it go.

Always Connected

Moshe wanted to produce something special in celebration of his oldest son’s bar mitzvah last year. A few weeks before the bar mitzvah, he heard some compositions singer Lipa Schmeltzer had put out for his youngest son’s bar mitzvah. He was taken by one of them, a soulful song about tefillin called “Geknipt and Gebinden.” The repeated lyrics, “Geknipt and gebinden, es vert nisht fashvinden,” about how the kesher between us and Hashem never gets lost, are suddenly interrupted by another line: “lomir reden ofen, let’s talk openly about how people find tefillin hard.”

This resonated deeply.

“While I never went off the derech, I know what it’s like to feel dead inside even while sporting gekrazelter peyos,” Moshe says. “For struggling boys today, tefillin is sometimes one of the things that can go easily, a quiet rebellion without making a statement. Young people in pain don’t see the point of tefillin, they just don’t feel the connection to Hashem.”

He decided to go with what he refers to as Lipa-style in a bold, abstract painting depicting a rebellious teenager: smoking, wearing color, showing his muscles. Blood is even visible on his arms, representing serious acting out — yet the subject is still wearing tefillin.

“The connection is never lost,” Moshe explains. “Es vert nisht fashvinden.”

A

few weeks after we speak, Moshe emails me one more painting. I open the attachment to see a picture of a crowd of people standing, two surreal figures in blue, as sifrei Torah fly in the background.

I never shared this one, besides with my closest family, Moshe writes. I think that now, after talking about and around the story so much, I’m ready to share it.

He painted his dream, and now he’s ready to share his healing.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 978)

Oops! We could not locate your form.