Disappearing Memories

| February 6, 2024Working memory has nothing to do with intelligence or effort. It’s merely a deficit of our executive functions

Disappearing Memories

Hadassah Eventsur

Shira is ready to get started with Shabbos preparation. Bursting with energy, she enters the kitchen, but her mind suddenly goes blank. She mentally rehashes what she was planning to do, but comes up empty.

Blimi wants to prepare her guest room. As she starts making the beds, she realizes she forgot the pillowcases, only to get them and realize she took the wrong set. She goes up and down four times by the time the room is finally ready.

Devorah’s stomach turns to knots as she walks toward the coworker who has introduced herself multiple times, but whose name she cannot remember.

What these women may be struggling with is deficits in their working memory. Working memory is one of our executive functions. It’s our ability to hold information temporarily in our heads while we use it for a short period of time. We use our working memory for things like remembering a phone number while searching for a pen, gathering all the items necessary for a task, or keeping a short list of groceries in our head during a spontaneous shopping trip.

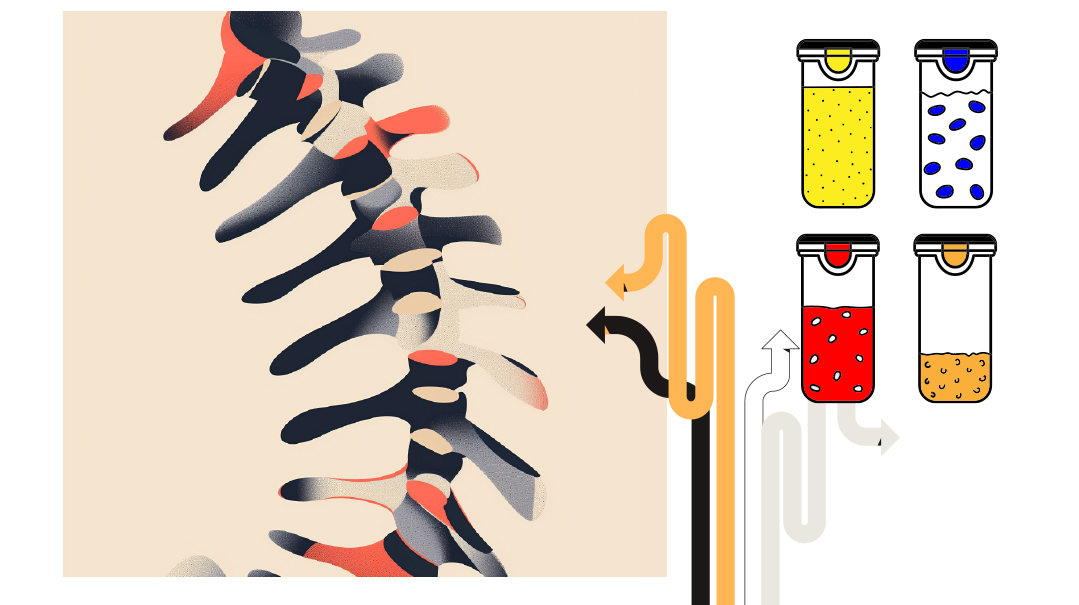

Picture a few dry erase boards on which you can write down bits of information as you need them in disappearing ink. One piece of information goes onto each board, and before you know it, the information is gone.

Everyone’s working memory has its limits. We all get a few slots and the information in those slots dissipates pretty quickly if we don’t actively work to retain it, essentially making space for new information.

Someone with working memory deficits essentially starts out with fewer dry erase board slots, and the information disappears more quickly than in neurotypical people. This is especially true when it comes to verbal and auditory memory. Even if someone who is neurodivergent has a typical working memory capacity, she is likely filling up more working memory slots with things like remembering to sit still or to keep herself from spacing out.

Working memory has nothing to do with intelligence or effort. It’s merely a deficit of our executive functions. If you struggle with your working memory, the key is to “offload” information from your head and onto paper or a device. Get used to inputting or writing down information instead of saying, “I’ll remember that.” In all likelihood, you won’t.

Using a Google calendar or a wall calendar is a great way to keep track of appointments or daily tasks. Make it a habit to input appointment reminders in your calendar as the receptionist at the office is scheduling them. You can set your device to remind you at various intervals during the day to make sure tasks get completed.

Vocalizing and repeating what you were planning on doing is another way to keep a task in your working memory for longer periods of time.

Creating “visual stories” helps with remembering people’s names. So when an acquaintance introduces herself as “Esther,” you can create a picture in your mind of this woman wearing a crown on her head. Or visualize a dollar bill on the forehead of your accountant, who is named “Bill.”

Being open about working memory deficits can also relieve the pressure of masking. Try saying things such as, “I struggle remembering names, so please don’t take it personally,” or “Whoops, I forgot to fill out the permission slip. Next time I’ll put it in a place where I can see it so I don’t forget.”

The more you learn about how your brain works, the more effectively you can compensate for working memory deficits and learn to be compassionate with yourself as you work with your brain.

Hadassah Eventsur, MS, OTR/L is a licensed occupational therapist with over 20 years of experience, and a certified life coach in the Baltimore, MD area.

Proactivity vs. Reactivity

Zipora Schuck

I recently flew on a flight filled with many families and noticed that other travelers were disturbed by the many children and teens walking up and down the aisle, seemingly oblivious to the seatbelt sign. Some pushed past the flight attendants coming down the aisle with drinks, while others spoke loudly throughout the flight, disturbing their neighbors. While personally I was happy to see cute children enjoying themselves, my “Karen lenses” left me uncomfortable.

If you grew up out of town like I did, your childhood may have been filled with cautionary advice about not making a chillul Hashem anywhere. We felt that world opinion about Jewish children could be made or broken with our behavior. I’m not sure if what’s changed is the dynamic of raising kids “in town’” or it’s just today’s times, but maybe that message has gotten diluted, to the extent of weakening two important social skills: situational awareness and hidden curriculum.

Situational awareness, or reading the room, is the ability to understand and respond to one’s environment or situation. It includes information gathering, observation, orientation, decision, and action.

Hidden curriculum means seeing and responding to less overt information and being able to react in an appropriately nuanced manner. It includes the unspoken values, beliefs, norms, and culture of a location that seem to be absorbed by those around us without even realizing it.

Help your children by discussing expectations before going to a new environment or reviewing when returning to one. What are the unspoken rules? What will others assume you know or expect of you? While some of these points may seem obvious, for some children they are too subtle to notice.

What is the expected behavior when going to a simchah? What does the nursing home staff expect when we visit? How should we act at an appointment? A minute or two of being proactive often saves much time being reactive after the fact.

Zipora Schuck MA. MS. is an NYS school psychologist and educational consultant for many schools in the NY/NJ area. She works with students, teachers, principals, and parents to help children be successful.

A Matter of Trust

Shira Savit

When a woman says, “If I start eating the cake, I won’t be able to stop,” what she’s essentially saying is: I don’t trust my body.

It’s easy to become consumed by strategies to avoid indulging in the cake — focusing on self-control, discipline, monitoring calories and sugar content, and seeking advice from neighbors and professionals. But we often overlook the most powerful tool available to us: trust, in ourselves and in our bodies. Learning to use the body’s innate wisdom to guide us in our eating might take effort and patience, yet it empowers us to both enjoy and regulate our choices.

In the next installment, we’ll delve into practical strategies to help us tune in to our bodies. Rest assured, with trust, you can learn how to have your cake and eat it, too.

Shira Savit, MA, MHC, INHC is a mental health counselor and integrative nutritionist who specializes in emotional eating, binge eating, and somatic nutrition. Shira works both virtually and in person in Jerusalem.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 880)

Oops! We could not locate your form.