Diary of No Despair

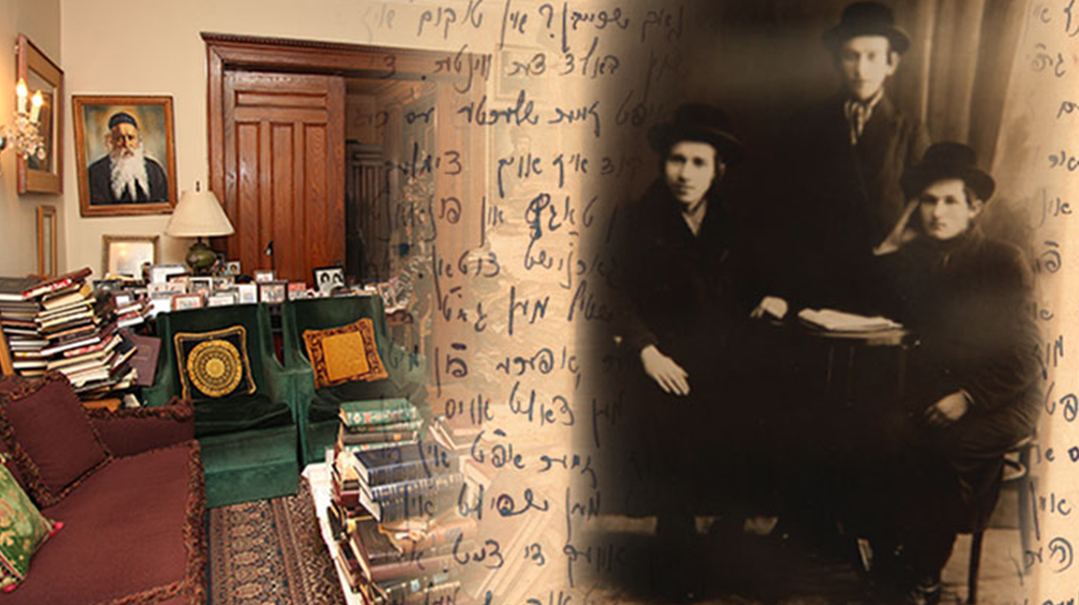

BELOVED BY ALL “It would have been worth opening the yeshivah just for Pinchas from Dukla” said Rav Meir Shapiro ztz”l referring to his prized student who knew all 2711 pages of Gemara by heart when he was yet a teenager. A young Reb Pinchas (left) with two friends Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin late 1920s; the Hirschprung study in Montreal (Photos: Moishy Spira Montreal)

N ineteen years ago the Montreal Jewish community mourned the passing of its much loved and esteemed chief rabbi the venerated Rav Pinchas Hirschprung. He was a man renowned for his Talmudic brilliance and eidetic memory; he was leader of a Bais Yaakov and a rosh yeshivah and the rebbi of his younger years — Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin founder Rav Meir Shapiro ztz”l — once remarked that “it would have been worth opening the yeshivah… just for Pinchas from Dukla.” He enjoyed a special relationship with the gedolim of the previous generation and especially with the Lubavitcher Rebbe who had his own talmidim forward their sh’eilos to the gaon of Montreal.

But most of all he was known for his sterling character and purity of soul — his humility kindness and compassion were legendary. “You never have to ask me to do a favor. Just tell me what to do for you ” he would often remark.

Nineteen might not be one of those round landmark numbers but this year 27 Teves was a significant yahrtzeit for family members and admirers who were able to connect to Rav Hirschprung’s special persona on a new level. Thanks to a largely unknown Yiddish memoir Rav Hirschprung wrote as a young man his unique voice still reverberates — and now that the manuscript has been translated into English and released as a book called The Vale of Tears that voice is accessible to everyone.

The memoir which chronicles the years 1939–1941 at the onslaught of World War II details Rav Hirschprung’s journey as a brilliant 27-year-old Torah scholar from his hometown of Dukla in southeastern Galicia across Nazi-occupied and Soviet-occupied Poland Lithuania and the Soviet Union to Japan Shanghai and eventually to Canada securing passage on the last boat to leave Shanghai before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. He wrote the journal in 1944 three years after arriving in Montreal and although the memories were fresh the full extent of the tragedy was still unknown — including the murder of his parents sisters and his beloved grandfather Rav Dovid Tzvi Sehmann (known as the Minchas Soles) Dukla’s esteemed rav and Rav Hirschprung’s primary teacher.

It’s a memoir he felt compelled to write despite the discouragement of some Torah scholars who believed that this kind of honest emotional writing was demeaning to a talmid chacham. He disagreed. “I told myself that it was in no way demeaning for a Torah student to fulfill the commandment to ‘remember what Amalek did to you’ by describing at least a bit of what I’d seen with my own eyes” the Rav once told a family member.

Rav Hirschprung’s The Vale of Tears which was translated by Vivian Felson and edited and published by the Azrieli Foundation is more than just a chronological journey across territorial borders; it’s a metaphysical journey over time. The universe the Rav portrays is not black-and-white; it’s one in which gradations within the human spirit are recognized while spiritual insights are shared at opportune times and from the most unlikely of prophets — such as the Christian woman who when watching the Jewish exodus from Dukla answered the Nazis “The Jews’ G-d is here. He who took revenge on Pharaoh Haman Titus and Sancheriv… will also take revenge on you.”

It’s a deeply personal memoir. But in the hands of this master storyteller it’s not only a testament to a lost era but to the human spirit that is capable of transcending physical and emotional adversities terror despondency and disillusionment when an abiding faith in G-d and commitment to one’s higher purpose remains one’s driving principle.

Despite Rav Hirschprung being such a private person daughter Carmella Nussbaum is not surprised her father wrote these deeply personal and revealing memoirs. The war had impacted him profoundly: He told her mother — Rebbetzin Alte Chaya a”h — that there wasn’t a day that went by that he didn’t think about the war. It was therefore something he needed to do for himself. But what was surprising to her and her siblings is that Rav Hirschprung never spoke about the book; in fact most of them didn’t even know it existed until a close friend brought a copy to the shivah house after their father’s petirah.

In many ways the book confirmed what they already knew about their father: how meaningful prayer was in his life how — surrounded by death and destruction — he would find comfort in learning Torah and that even as a young man he had that heart of gold they all recognized. Its immediacy though better helped them appreciate just how difficult those years were for him. “How hard it was saying goodbye to his parents. How much he loved his grandfather. His memories are so raw and real ” daughter Rochel Newman says.

Since she first read the memoir Sossy Hirschprung has been similarly taken by the loving way in which her father portrays his community and by how much the Jews of Dukla loved her great-grandfather who had impacted her father so profoundly throughout his life. “My father said that before any major event in his life his grandfather came to him in his dreams.”

Over the last ten years beginning a month before his yahrtzeit she and her sister Rochel reread their father’s book. “Every time I read it it touches me the same way it did when I first picked it up ” Mrs. Newman says.

Everyone Out

Rav Hirschprung was born in the city of Dukla in 1912. Gifted with a compassionate heart brilliant mind and photographic memory he became a primary student of Rav Meir Shapiro — founder of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin and the Daf Yomi movement who once said of him that while still a youth he already knew all 2 711 dapim of Gemara by heart. By the time he was a teenager he had already written two seforim and when Rav Shapiro passed away in 1933 it was Rav Hirschprung who would test the prospective talmidim — required to know 200 dapim of Talmud by heart to gain entrance.

Rav Hirschprung married Canadian-born Alte Chaya Stern daughter of Montreal’s G-d-fearing shochet in 1947 (they had nine children together) and served as the chief rabbi of Montreal from 1969 until his passing in 1998. He founded the Bais Yaakov of Montreal back in the 1950s that now carries his name and he also served as rosh yeshivah of Yeshivas Tomchei Temimim in Montreal.

Although he arrived on safer shores and was a builder of one of North America’s largest Jewish communities the war years left an indelible patch on his heart — and the tragedies he witnessed together with his own personal miraculous salvation were always at the forefront of his motivation to rebuild a lost Torah world. “If I survive this war I’ll dedicate my whole life to Torah ” he pledged when he was on the run. And he did.

Succos, September 1939.

The 27-year-old Pinchas Hirschsprung, who had earlier returned to Dukla, had just been summoned to Gestapo headquarters. He had been unofficially designated “Herr Rabbiner,” after his grandfather’s escape to neighboring Rymanow. The news they delivered was startling. “Dukla must become Judenrein,” the Nazi storm trooper declared. He announced that the Jews had just 16 hours to leave, with permission to take only what they could carry. The young rabbi was stunned, and in the name of G-d, tried to appeal to their sense of justice. But his supplications produced the opposite effect. Infuriated, one of the Nazis removed his revolver, told him to say his last prayers, and to turn his head to the wall.

These words were ironically comforting. At least, Rav Hirschprung thought, he wouldn’t have to be the one to give his community the order. “I prepared for my execution. I recited Shema Yisrael, said Vidui, and with my face to the wall, quietly recited, ‘Let my death be atonement for all my sins.’ ” In the end, it was Rav Hirschprung’s wholehearted acceptance of death that turned the tide for him. Not wishing to give him such “pleasure,” his executioner insisted that he carry out his assignment first and then present himself to die.

It was a transformative moment for him. “During the course of reciting the Shema Yisrael — and I myself do not know how this happened — I was suddenly transformed into a new person. I had become hardened. I showed no reaction, no hysteria. I looked objectively at the situation and made peace with my fate — to become the messenger of such ‘glad tidings’ — namely, the expulsion of the Jews.”

The fate of Dukla’s Jews was sealed. But perhaps their hardships could be lessened. He asked to speak to the commander, and appealed to his better instincts. Perhaps 50 merchants could remain behind to supply Gestapo army barracks with necessary goods? Perhaps the Gestapo could supply wagons so that the elderly, women, and children needn’t walk, and perhaps these individuals could take with them additional belongings? Touched by his sincere concern for his community, the Nazi commander actually granted his requests and told him to compile a list of 50 such individuals. Refusing to arbitrate their fates, he increased the number, placing the burden of arbitration on the commander. He didn’t include his father’s name on the list for fear his objectivity might be questioned. Impressed, the commander allowed all 63 people on the list to remain, as long as he, Herr Rabbiner, assumed personal responsibility for his community’s orderly exodus.

Transformative moments like these do not happen in a vacuum; they are the end product of a psychological and spiritual process. Rav Hirschprung understood that. In structuring his book, he builds up to this pivotal moment wherein he assumes the cloak of leadership that was thrust upon him, a process, he indicates, that began weeks before at the onslaught of war.

Dukla, Rav Hirschprung writes, was a pious, quiet shtetl with Jews and Christians living harmoniously together. Its Jewish residents were mostly merchants who did business with each other “without competition and without the least ambition of becoming wealthy.” As elsewhere in Poland, late 1939 brought with it confusion and uncertainty. Illusions ran rampant. Many refused to believe that the Germans were fighting a real war, rather a war of nerves. And those who conceded that the war was real were convinced that Poland was strong enough to hold off Nazi aggression.

Rav Hirschprung had no such illusions; he writes that his heart broke for those Jews who clung to false hope. As Polish cities fell, and as German forces swept closer to Dukla, reality hit full force. Even before the Germans arrived, Jewish life became unbearable. Daily decrees restricted religious observance, while Ukrainian residents felt free to rob Jewish merchants of their wares. Initially Rav Hirschprung and others decided to leave for neighboring villages, but while they thought to escape death, they actually moved toward it. For Rav Hirschprung, however, it was his mother’s supplication asking him to return to Dukla that possibly saved his life; many of those who had left with him were later killed by German bombs.

In Safe Hands

For some sensitive souls, the disintegration of their world was too much to bear. Some, Rav Hirschprung writes, lost their minds. How was one to find inner strength in such adversity? How was it possible to maintain one’s faith in an Orwellian universe spinning out of control? But it is precisely in Klal Yisrael’s faith in G-d that its strength resides, a strength that transcends nature. This profound truth was revealed to him in those panic-stricken Jews hiding in cellars who, despite their terror, “chanted their Shabbos prayers… partook in the third meal… and performed the Havdalah ceremony.”

And when overcome by personal despondency, he recalled his grandfather’s words reminding him that relief resides within distress itself — that there is a purpose to pain and suffering. By immersing himself in prayer and by retreating into his “four cubits of halachah,” he mined that purpose, and in doing so found relief. “The melody [of learning] itself led me to ‘the world of complete good’ … It filled my senses … and freed me from my mental and emotional confusion, and in me was born a kind of holy insight… that led me to true self-nullification before the … Eternal One.”

Days prior to his community’s unexpected expulsion, Rav Hirschprung had a revelation — that he should cross the Soviet border and go to Vilna, where the gaon Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzensky resided. Attaining that goal became his higher purpose, although he would have to overcome many obstacles and tests to fulfill his plan. When he shared his plans with his parents, though, they gave their blessing — unaware that they, together with the rest of Dukla’s Jews, would soon be sent to their own deaths.

To avoid patrols on each side of the border between Nazi and Soviet-occupied Poland, Rav Hirschprung and his friends were forced to cross the San River, which was deeper and more turbulent than expected; their wet clothes weighed them down. Losing their bearings, they silently cried out to G-d for help. As they sank deeper into the mud, they stopped fighting the waters and placed themselves “in the hands of fate as rock-solid waves carried us forward.”

Placing oneself in G-d’s hands is a theme that reverberates throughout this memoir. At a crowded train station, Rav Hirschprung finds himself beside a simple Jewish woman and her two children, who articulates to him her profound belief in Divine providence and shares with him her personal story of survival — a story that he says strengthened his own faith. During the Warsaw bombings, she and her children sought shelter in a cellar filled with Poles. They begged her to leave, convinced that as a Jewess, she would cause G-d’s wrath to fall upon them by killing them all. When she and her children emerged from the cellar, a bomb hit the shelter, killing everyone inside. Where she was going now, she did not know, but what she did know was that G-d would continue to accompany her wherever she went.

For Jews, the existential challenges inside Soviet-occupied Poland were ideological and spiritual, as well as physical. The Communists offered the Jews the same privileges as everyone else, on condition that they accept Marxist ideology and atheism. And so, cities became filled with lice-infested refugees escaping from Nazi terrorism. The fortunate ones were stuffed into overcrowded local residences that had been requisitioned by the state. The less fortunate slept in cold synagogues or in hallways of cheap inns on straw mattresses. And there was no chance for work, not if one wanted to keep Shabbos or renounced atheism. They were frightened, lost, and forlorn.

All Roads to Vilna

Rav Hirschprung’s shoes had fallen apart months before; he now bound his swollen feet in rags. Days could go by without as much as a slice of bread to eat. A deep frost had set in, and he had no winter clothes to keep out the cold. Yet despite these seemingly never-ending hardships, he retained his humanity: After lining up for over 12 hours for a loaf of bread, he was approached by an elderly Polish lady, who politely asked that he sell her half his loaf, since she had problems with her legs and could not stand in line. Without hesitating, he took out a knife, cut his precious loaf in half, and gave it to her, while refusing to take payment.

His desire to reach Rav Chaim Ozer intensified daily, as did the obstacles preventing him from doing so. There were enough reasons not to go. A recent pogrom there had killed numerous Jews, and many believed the Soviets would soon invade Lithuania and that its independence was short lived. In every town he visited from Lemberg to Lutsk, he sought the advice and blessings of the gedolim residing there — Rav Benzion Halberstam, Rav Menachem Mendel Horowitz, and the gaon Rav Aaron Lewin. The greatest encouragement came from Rabbi Zalman Sorotzkin, the Lutsker Rav, who informed him that he, too, longed to go to Vilna and that he only remained in Lutsk at the request of Rav Chaim Ozer himself, in order to counter the influence of Communism. He then gave him precise instructions on how to sneak across the Lithuanian border.

But crossing that border remained challenging. With feet wrapped in rags and no winter clothes, he aroused suspicion and was quickly picked up by the border police. Countering these obstacles were spiritual messages coming his way, which strengthened his resolve. One was from his grandfather, who in a dream reminded him that Hashem sends signs every moment of our lives through trials and tribulations, as to how to draw closer to man’s “eternal purpose.” The other was from a mystical rabbi, a watchmaker, who assured him that he would succeed in his quest to reach Rav Chaim Ozer because Vilna represented to him his soul’s desire, which was eternal, whereas these obstacles holding him back were temporary.

The obstacles may have been temporary, but they were stubbornly persistent — albeit ultimately purposeful. Rav Hirschprung was picked up yet a third time by the border police; but this time he was placed in a truck with other Jews. Where they were being taken, they did not know. Still, he recognized that a miracle had happened to him. Had he not been picked up, given the condition of his feet, he would not have been able to cross the border or return to town, but would have frozen to death.

Under heavy guard, they were taken into a large, dimly lit room in what appeared to be a military headquarters, where detainees were lying on the floor. But the layout of the rooms and the building’s outside construction appeared vaguely familiar — more like a shul or yeshivah than a military site. “Where am I?” he asked himself. “Am I awake or am I dreaming?”

He was both awake and dreaming. He was in Radin, and in the Chofetz Chaim’s yeshivah. Realizing this, his “entire body began to tremble… and out of sheer ecstasy, my eyes welled up with tears. I began weeping like someone condemned to death who is unexpectedly pardoned. I felt as if the spirit of the holy tzaddik, the Chofetz Chaim, was hovering over us, caressing his children.”

Rav Hirschprung was fortunate: The Soviets were not the Nazis. After reprimanding him for his blindness in not recognizing “the historical process” that was taking place around them, and his ingratitude to those who offered him equal rights, the official told him he was free to go. As grateful as he was to be in Radin, he understood that his higher purpose lay in Vilna. The watchmaker’s predictions were realized. On his fourth try, and after a grueling nighttime trek over mountains and across rivers and forests, he finally crossed the Lithuanian border.

Vilna — the Jerusalem of Lithuania: Yeshivas Mir, Kamenitz, Bialystok, Kletsk, Ostrowiec, all sustained under the careful and loving watch of the gaon Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzensky. And now Rav Meir Shapiro’s Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin would be added to this illustrious list. Previous attempts to reopen the yeshivah had failed, but Rav Chaim Ozer encouraged Rav Hirschprung to move forward and try again. These were heady times for Rav Hirschsprung, as the yeshivah took shape: Money was raised from neighboring towns, a permanent location was found, and students began streaming in as more of them crossed the border.

But it was not to last. Authorities began jailing illegal refugees and that included yeshivah students, and Soviet troops were flooding into nearby Eyshishok. Rav Chaim Ozer tried to fight back, sending a delegation to Kovno to speak with the Refugee Commissariat and distributing money for redeeming captives, while trying to secure certificates for yeshivah students to go to Eretz Yisrael. There were some temporary victories: Rather than return these illegals to Soviet- and Nazi-occupied territories, yeshivos were asked to relocate outside Vilna, with many students heeding the call. Rav Hirschprung, though, decided to keep Chachmei Lublin in Vilna, which ultimately enabled all of its students to emigrate. Through the joint efforts of the Dutch and Japanese consuls, visas were issued for the Dutch West Indies, which would require their traveling through Japan, a country still open to these battered refugees.

The ultimate battle, though, was lost. After the Soviet invasion, Rav Chaim Ozer was unrecognizable. In the great panic and chaos sweeping through the city, yeshivah students had flocked to him for support and encouragement — but at that point there was none to give. Since the Soviets’ arrival, Rav Hirschprung writes, Rav Chaim Ozer had been consumed with worry that the Communists would close down the yeshivos. He also understood that his own end was near. Rav Chaim Ozer’s petirah was felt worldwide, but especially among the yeshivah students living in Lithuania, who had found in him a father who cared deeply for the spiritual and material well-being of each and every one of them. Weeks later Rav Hirschprung would leave Eastern Europe, but it was the Torah he absorbed there directly from these Torah giants that he carried with him to Montreal, enriching generations to come.

Finding Comfort

Although most of his siblings hadn’t even known about the memoirs until their father’s passing, Reb Yitzchak Hirschprung was 14 when he found out about the manuscript and read it in the original Yiddish, asking his mother to help out if he didn’t understand a word or phrase. He’s read it numerous times since, and the words continue to inspire him. He says it’s what helped him to fully understand the words “yismach lev mevakshei Hashem — happy is a person who searches out G-d,” because “in the worst situations, my father was able to turn to Hashem and feel His comfort in very tangible ways.” He also values his father’s profound insights — “like how when he sees the Germans marching into Dukla for the first time, he is struck by how each one of them, in their ‘robotic mechanizations and steely rigidity’ physically resemble each other, as if they were mass-produced in a factory. He felt it was an analogy for how their science and technological power was being used for evil, and how dangerous this power is without kedushah.”

Yet despite the pain he experienced and the evil he encountered, Rav Hirschprung always retained his faith in humanity, harnessing the pain of loss and destruction to propel him forward.

“He loved people. He loved life, and he loved you for who you were,” says his daughter Carmella. “Even though he was involved in the klal, he never overlooked the yachid in the klal. He was a visionary, but he never only saw the forest — he saw every tree in the forest.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 646)

Oops! We could not locate your form.