Diamond in Disguise

| September 5, 2023What could be wrong with my perfect twins?

Lam’natzeiach mizmor L’David...

I

awoke with a start, a dull ache in my back. I blinked. Where was I again?

I looked down at the hospital bracelet around my wrist and then out the window at the hills and stone buildings. Right. I was in Israel, and I had just given birth to twins — a boy and a girl — several hours before.

I should be elated, I thought. But something didn’t feel right.

Born at 36 weeks, the twins were preemies. My son, who had been the bigger, stronger one all along, was taken to the nursery at 2.9 kilos; my daughter, a whole kilo less than her brother, was sent to the pagiyah — as they called the NICU in Shaare Zedek hospital.

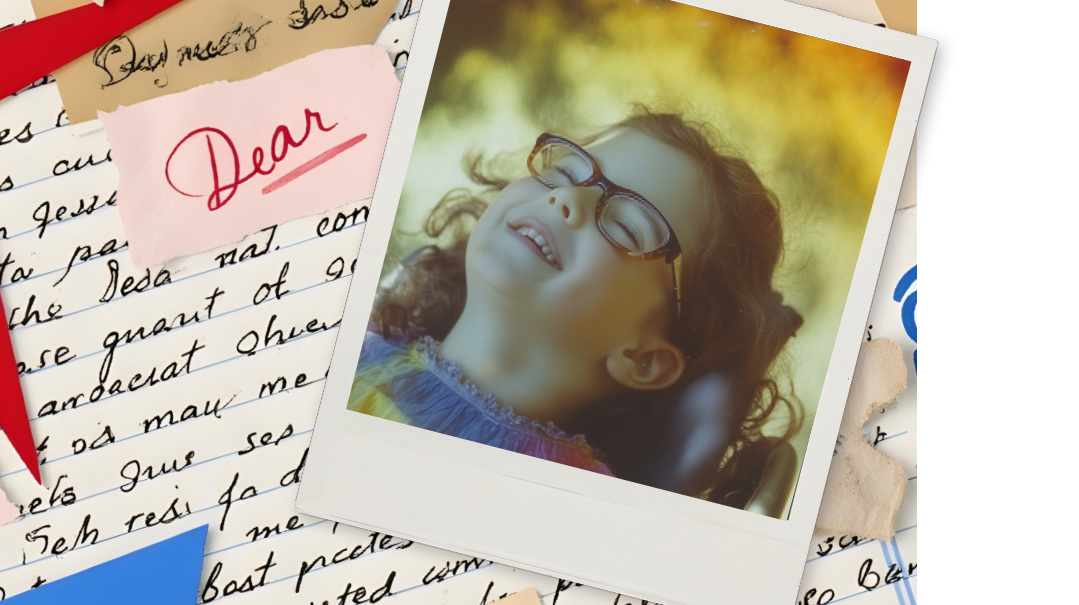

I had held them each for a few minutes before they were whisked away. When my daughter had been handed to me, bundled up in a blanket, I gasped. She had the most adorable, angelic face with ribbon lips, a perfect chiseled chin, and a button nose. A certain calmness exuded from her.

“She’s gorgeous,” I breathed. The nurses nodded eagerly and chorused their agreement before pulling her away. The next thing I knew I was brought to a different room where I fell asleep. When I awoke several hours later, I felt empty. With my other births, I had spent the hours afterward cuddling and bonding with my newborn.

“I want to see my babies,” I insisted when the nurse came into the room.

“The boy needs to stay in the nursery. His oxygen saturation isn’t what it should be,” she replied. “And the girl is in the pagiyah. I can ask someone to bring you there by wheelchair.”

I had a feeling my son’s oxygen was just fine, and he just needed his mother. I went to the nursery and sat with him for 30 minutes. Less than an hour after I got back to my room, they wheeled him in.

“His oxygen saturation stabilized,” the nurse said. I smiled. A mother always knows.

Then it was time to go to the pagiyah. A sinking feeling crept into my heart. My other children at home had been born at around eight pounds, healthy and strong. This little girl was less than five pounds. At birth, she had let out a little squeak instead of a cry. She seemed more like a doll than a person.

When I was sitting in the pagiyah, cradling her in my arms, the sinking feeling only intensified. Her limbs fell to her sides like a rag doll. I assured myself that it was probably because she was a low-weight preemie, and she’d be back in shape in no time. If there was a real issue, they would have told me by now, I rationalized. After all, that’s what would have happened in Cleveland, where my other children were born. We’d been in Israel only three months, and I didn’t stop to think that perhaps things worked differently here.

Ad ana Hashem tishkacheini netzach…

When I found out I was expecting twins during my routine nine-week pregnancy ultrasound, I screamed.

“What?! Are you sure?” Twins don’t run in my family, so I was shocked.

I burst into tears when I was shown the two sacks on the computer screen. I felt Hashem’s love for me so intensely at that moment that I wanted to encapsulate it and hold on to it forever. I had worked on myself a lot internally over the previous few years, and this felt like a sign of approval from Above.

But like a heartbeat, a down follows every up. Several weeks later, after another routine ultrasound, as I was admiring printouts from the ultrasound technician of “Baby A” and “Baby B,” a nurse mentioned that the doctor wanted to see me in her office. I frowned. What could be wrong with my perfect twins?

“The nuchal translucency is a bit high on Baby B. There’s a 17 percent chance of a genetic disorder.”

“Nuchal what?”

“The fluid behind the neck. We measure it during the 13-week ultrasound.”

She started talking about genetic counseling and amniocentesis, so I could decide how to proceed with the pregnancy, but I was in a haze.

“Ummm, I need to talk to my husband first,” I answered. I realized that a rav would advise against those actions, but I didn’t want to butt heads with the doctor, who seemed convinced that knowing exactly what was going on was the way to go.

When I got into the car, I began grasping at straws. What could I give up; what could I do differently to convince Hashem to take this nisayon away? I searched my brain for something that felt meaningful, but it came up blank.

Finally, I burst into tears.

“Hashem, I have nothing to give You at this moment. All I know is that I’m relying on You.”

The fear in my heart dissipated, and I could breathe again.

Ad ana tastir es panecha mimeni

IT was Sunday afternoon, two days since I’d given birth, and my third time in the pagiyah. I was looking at my daughter’s swollen eyes, and I realized something was off.

“Is everything okay with her eyes?” I asked a nurse, trying to keep my voice decibels from rising along with my heart rate.

“Yes, yes,” she reassured me.

“What about her muscles? Why is she so floppy? Is it just because she’s a preemie?”

“Yes,” the nurse reassured me again.

But this time I wasn’t convinced.

Something was wrong, and I knew it instinctively. I felt like sharp arrows were piercing my chest. I put my daughter down and fled back to my room.

When I got there, the phone rang, but I hadn’t yet caught my breath.

“The doctor in the pagiyah wants to talk to you.”

No. No. No. I couldn’t. Why didn’t they tell me as soon as she was born? My heart contracted in agony. The twin girl of my dreams had died, and I would need to bury her now. Bury her and accept a new reality.

My husband called the next moment. “I’m going to the pagiyah now,” he said. His happy-go-lucky voice told me he had no clue.

“I think she has Down syndrome,” I blurted out.

I eyed the matching pom-pom hats I had bought in anticipation of this birth. One had a blue pom-pom and the other a pink one. Sometimes the darkness is so thick it chokes you. I grabbed the pink pom-pom hat and looked out the window at the cloudless azure sky. “My heart is completely broken,” I whispered to Hashem.

Ad ana ashis eitzos b’nafshi, yagon bilvavi yomam…

“You should have known,” one doctor insisted when he saw the devastating shock I experienced upon finding out that my daughter has Down syndrome. “The nuchal translucency was high.”

I felt a pang. Was I to blame, then, for not emotionally preparing myself? I recalled the 20-week, in-depth anatomy ultrasound where not only was the nuchal translucency declared normal, but the doctor had told me that the babies looked beautiful, and no other signs of genetic disorders or heart problems were found.

They had warned me that there was still a small chance — less than ten percent — of a genetic disorder, but after I saw a 3D picture of Baby B, I felt certain everything would be okay. Even in the womb, I could see her delicate features and she looked perfect. Besides, there was a lot going on. We were in the middle of moving to Israel and I was knee-deep in making difficult decisions.

Besides, having a baby with Down syndrome wasn’t something I felt I could handle.

And Hashem only gives a person a nisayon they can handle.

Right?

Ad ana yarum oivi alai, habita aneini Hashem Elokai, ha’irah einai pen ishan hamaves, pen yomar oivi yichaltiv, tzarai yagilu ki emot

When my 12-year-old sister was critically sick, I’d started saying perek 13 in Tehillim since it was one number above her age (a segulah that the choleh should make it to the next year, which she tragically did not).

Nine years after her passing, when I found out about my daughter’s Down’s diagnosis, I recalled the raw, painful nature of that perek and its hopeful end. I felt drawn to it. I repeated it over and over again, to remind myself that these feelings of despair and abandonment would eventually give birth to hope and closeness.

Hashem, when will You finally remember me? Am I destined to remain in this dark tunnel forever? I feel like my life is over. Will I ever see the light of day?

V’ani b’chasdecha vatachti, yagel libi b’Yeshuasecha

WE named our daughter Pnina Esther.

Pnina because of my grandmother, who had passed away a year and a half before, and Esther because she was born a few days before Purim. I later realized how fitting this name was for her. Pnina Esther — a hidden pearl, an allusion to her extra-lofty neshamah, which every child with Down syndrome has.

A week after giving birth, I went home with Pnina Esther’s twin brother, Yekusiel Yehuda. Pnina Esther remained in the pagiyah because she couldn’t suck well and thus couldn’t drink from a bottle. Otherwise, she was generally healthy, baruch Hashem.

For three weeks, I traveled back and forth from my house to the pagiyah to spend a few hours with Pnina Esther. After those three weeks, I had a sudden inspiration to spend Shabbos in the hospital with my baby; I just couldn’t imagine how I would spend another Shabbos without her. My family felt incomplete.

That Shabbos, I began to separate Pnina Esther from her Down syndrome. The 3D picture from the ultrasound hadn’t lied; Pnina Esther has beautiful, soft features. I also noticed her determination and grit. She was being woken up every two hours to practice bottle feeding, and it took her at least half an hour to down the two ounces that was expected of her. But she kept at it, with a certain grace. She was already inspiring me.

I was reminded of my grandmother, her namesake, who grew up in Soviet Russia. She loved telling us about how she was a straight-A student who graduated with honors as valedictorian. In college, she studied to become a chemical engineer, but she gave up lucrative career opportunities to move her family to America in her forties, where she started over, mastering the language despite her age and becoming an accountant to help support her family. Babushka was an extrovert who loved people, and despite her accomplishments, there was nothing intimidating about her. I never felt pressured by her to be someone I’m not.

By the end of that Shabbos, they told me that Pnina Esther could be discharged.

My daughter was coming home.

Ashirah LaShem

IN my quiet moments at home with Pnina Esther, I began to sift through my thoughts and feelings.

I realized I had needed those twins to feel worthy. I’d been struggling with doubts about my parenting. So when I found out I was expecting twins, I felt like it was an external validation from Above, proof that Hashem trusted me with raising not one, but two more children.

When my daughter was diagnosed with Down’s, it catapulted me back into insecurity, to judging myself by how others view me. Pnina Esther’s diagnosis forced me to take a step back, do more inner work, and acknowledge that I had value all along.

I made a decision: I refuse to become jaded — to look at life with a cynical eye. Instead, I started to notice all the gifts I once took for granted. The three beautiful healthy children I had before the twins, all of whom are above and beyond anything I ever could have dreamed of or expected. How incredible it was that Pnina Esther was given to me together with a healthy son. My friends and family and the supportive people in my life. The incredible Hashgachah pratis that our new home in Sanhedria Murchevet had at least four children with Down syndrome in the surrounding buildings; I literally had a built-in support system.

Ki gamal alai

I look at my new baby daughter. Her future seems so uncertain. Will she always look so delicate and precious? What will she be able to accomplish? Will there eventually be a cure for the symptoms of Down syndrome so she can be on par with her peers?

Nothing of the future is known, of course, and nothing is certain. The only thing that is certain is this beautiful moment right now as I close my sefer Tehillim and stare lovingly at my daughter. Pain, I see, is not for naught; pain is but a vessel for light.

Suddenly Pnina Esther opens her eyes wide. I smile at her, and she surprises me by offering a gummy smile of her own — a smile that could melt one thousand stony hearts.

Tears of gratitude fall from my eyes onto her cheeks.

You don’t need to be perfect, I think, to be so deeply loved.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 859)

Oops! We could not locate your form.