Death Guard

The details of Israel’s only execution were nearly buried together with the man who pulled the lever

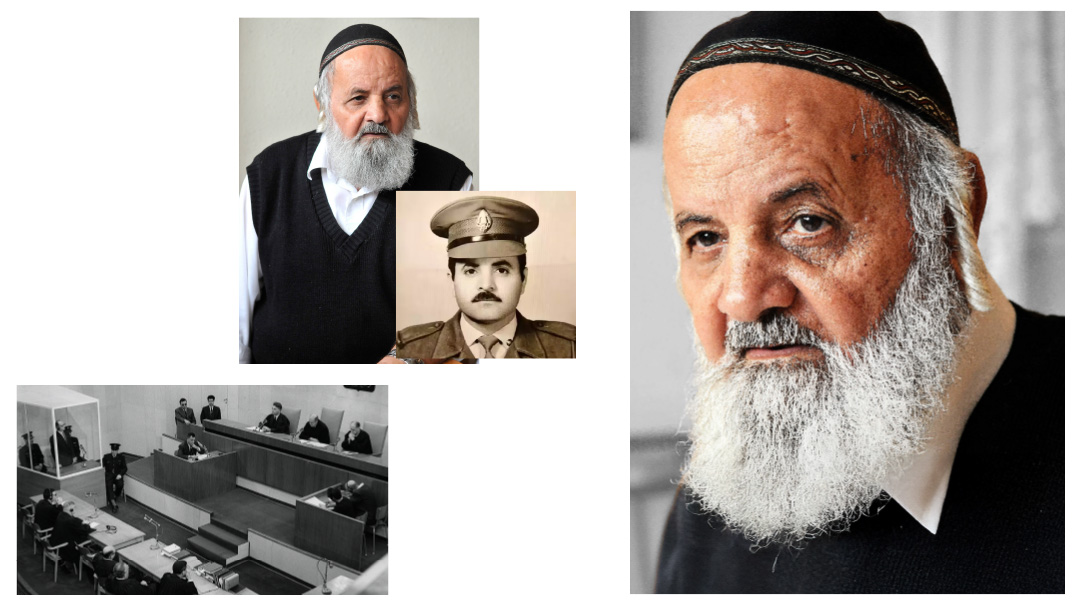

Photos: Flash90, Mishpacha archives

When 88-year-old Shalom Nagar passed away last week, a little-known chapter in Israel’s history was almost buried with him. For Shalom Nagar was Adolf Eichmann’s personal prison guard, and the one who pulled the lever once the noose was around his neck. Yet for years, the details of Israel’s only execution were shrouded in secrecy — until a Mishpacha conversation with Reb Shalom once the gag order was lifted

You might have seen the notices this past week about an elderly Yemenite fellow named Shalom Nagar, an 88-year-old shochet and kollel avreich from the Tel Aviv suburb of Holon, who passed away. But what you might not know is that this friendly, young-at-heart octogenarian with a pithy sense of humor and indefatigable spirit was in fact the Jewish prison guard who sprung the gallows floor under arch-Nazi Adolf Eichmann in Israel’s first and only execution back in 1962.

Nagar’s story as “Eichmann’s executioner” gained traction over the last few years, yet long before Reb Shalom became a popular interview subject for historical documentaries, Holocaust memorial clips and even class projects, I had found out about him through a contact of Rabbi Amnon Yitzchak, the famous Yemenite outreach rabbi who was instrumental in bringing Reb Shalom and his wife Ora back to a life of Torah and mitzvos.

Until then, the details of Eichmann’s hanging by the State of Israel were shrouded in secrecy — from Eichmann being given his last glass of wine to the noose being placed around his neck, to his lifeless body being incinerated in a specially-designed oven and his ashes spread over the sea outside Israel’s territorial waters.

Most of those who were involved in Israel’s only execution are no longer living, and until 20 years ago, those who were, were under a gag order against revealing any details. But when I first met Reb Shalom and his wife in 2004, the time had finally come for him to open the door to his memories. And, I learned then, his life wasn’t only a story about how he was the one to pull the lever on Eichmann’s killing floor; it was the story of a young orphan from Yemen who struggled to find his footing in those tough years of austerity and forced assimilation, yet ultimately reconnected with the legacy of his holy ancestors.

“For years I was sworn to secrecy about Eichmann’s end,” Reb Shalom told Mishpacha at the time, obviously relieved — and happy — to finally be able to share his role in Eichmann’s demise. “My commanders feared reprisals from neo-Nazis and others who still considered Eichmann a hero. But Isser Harel, the Mossad chief in charge of Eichmann’s capture in Argentina, had already written a book about it. What did I have to fear? Besides, I was involved in the great mitzvah of wiping out Amalek.”

Adolf Eichmann, the engineer and supervisor of Hitler’s Final Solution, bore the primary responsibility for the systematic murder of six million Jews in the Holocaust.

He was born in 1906 in Solingen, Germany, but after his family moved to Austria, he joined the Austrian Nazi Party, where he soon found a place for his bureaucratic talents. In 1939, back in Germany, he headed the “Jewish desk” of the Gestapo and spent the next six years implementing Hitler’s “Final Solution,” perfecting the murderous efficiency of the death camps and gas chambers. After the war he went into hiding to avoid the Nuremberg war-crimes trials, and then made his way to Argentina, where he lived in relative security with his wife and four children as an anonymous manager of a laundromat. For years the Israeli Mossad was on his tail, and in 1961 he was captured and hauled off to Israel to stand trial for the genocide of the Jewish people.

The trial, which publicly rehashed the horrors the Nazis perpetrated against the Jews, elicited a torrential emotional response in Israel and around the world. In Israel, it was the first time the Holocaust was allowed to go public, at least for the hundreds of thousands of survivors who made their way to the Holy Land, only to be disparaged and ridiculed, as if being a “survivor” was a stain on the image of the proud, brave “new Jew.” When Holocaust survivors began flooding Eretz Yisrael after the war, the Zionist settlement felt itself in danger of losing its hard-won image as a proud, independent, uncompromising, and idealistic people claiming the Land through love and labor — unlike the frightened, beaten survivors, death-camp refugees who had been herded into ghettos and concentration camps without a fight.

The cruelest insult to these hapless, suffering refugees was the slang term coined for them — “sabon (soap)” — referring to the alleged Nazi practice of making soap out of their victims’ boiled bodies. To be a survivor meant shame, and so people quickly learned to sublimate their horrifying Holocaust experiences. Back then, heroes were black and white: the pioneering Jews of Eretz Yisrael building the land with their sweat and blood, or the brave Jews of Europe — forest partisans, underground rebels, or anyone else who picked up a gun and tried to shoot the enemy, not those who went “like sheep to the slaughter.”

The Eichmann trial would help change the narrative and excoriate the shame.

During the year-long trial, repressed memories finally burst forth in the standing-room only courtroom. People screamed, cried, and tried to attack and kill Eichmann, who was ensconced during the proceedings in his bulletproof glass box. The long, tortuous trial period was perhaps the first macro-level psychological treatment for Israeli society as a collective in processing the horrors.

On December 13, 1961, Eichmann was sentenced to death by hanging. Following the rejection of an appeal to the Supreme Court and a plea for presidential clemency, he was executed close to midnight on May 31, 1962. The following morning, a mere one-line announcement of his hanging was broadcast on Kol Yisrael, with no further specifics. Although the trial was in the spotlight for nearly a year, the details of his incarceration and of the execution itself would only be revealed decades later by his executioner, Shalom Nagar.

Shalom Nagar was born in 1936 in the Yemenite village of Saana. Although his Holocaust education came with the Eichmann trial, he remembered that his father went to search out hideout caves in the mountains in the event that Hitler’s long arm reached Yemen. His father died when Shalom was seven, leaving his mother a helpless widow with five children.

“She was a pretty woman and soon was offered a marriage proposal, but after the wedding her new husband reneged on his promise to take us all in,” Reb Shalom told me. “But somehow, we all found our own way. My sister was 13 so they married her off. My older brother was able to take care of himself, another brother went with my uncle, and my little sister was permitted to stay with my mother. I, however, was on the street. In Yemen, orphans were taken to the State orphanage and forced to convert to Islam, so I made sure to find shelter among the Jews. During the day I worked as a porter or at other odd jobs and was given food, and at night I slept under the stalls in the market. What saved me was my father’s tallit, made of goat skin and strong like the Bedouin tents. For six years I wrapped myself in his tallit and that kept me warm at night.”

Then the wave of Yemenite immigration to Israel began. Shalom and his brother made their way by foot through the desert — where they would cover each other with sand at night to keep warm — to the Aden port, where Jewish Agency representatives prepared the airlifts.

“As soon as we got on the plane, they cut off my peyot,” Reb Shalom sighed, as if he still felt the scissors on his head as that helpless 13-year-old boy. “They told us that in Yemen we need peyot to separate ourselves from the Arabs, but in Israel everyone is Jewish. Besides, they gave me a bar of chocolate so I wouldn’t be too upset. My brother started to scream, and put his hands over his ears to protect his locks. Eventually they left him alone.

“They took us to Kibbutz Shefayim. We walked into the dining room and were shocked — no washing, no brachot, no head coverings, what kind of Jews were these? My brother was suspicious: Maybe they want to convert us? Who knows what kind of food they’re giving us. So he said, ‘Let’s wait until tomorrow and see what happens.’ Well, the next day they took us swimming, boys and girls together. My brother went crazy. In Yemen you ran across the street if you saw a woman approaching. So we ran away, and made our way to the Rosh Ha’ayin transit camp, where at least we were with our own people. The social worker there threatened that we wouldn’t get food ration coupons, but we relied on the goodness of our fellow Yemenites who wouldn’t let us starve. In the end they sent me to a religious youth village at Kfar Haroeh.”

Nagar joined the army at 16, and then went on to serve in the Border Police. “They were offering housing during the week, and since I was basically homeless, I figured it was as good a choice as anything,” he said.

Then Nagar joined the Israel Prison Service working as a guard, which brought him to that fateful night.

“At first Eichmann was brought to a prison in Yagur outside of Haifa, and was transferred to Ramle Prison, where I worked, for the last six months of his life,” he related. “We were a unit of 22 guards, known as the ‘Eichmannn guards.’ We were carefully selected to make sure we had no revenge motives, and were the only ones who were allowed contact with him. None of us were Ashkenazim — that would have been too dangerous. It was just 16 years after the Holocaust and many prison employees had either gone through the camps or had lost family. The government, for their part, wanted the zechut of killing him and so they couldn’t have anyone taking personal revenge, although countless people would have loved to get their hands on him.

“Eichmann was in a special wing of the prison, on the second floor, imprisoned in an inner room within other rooms. For six months I guarded him in the innermost room, standing in close proximity when he rested, wrote his memoirs, ate, and used the facilities. He might have wanted to take his own life, and we were to prevent that at all costs. Outside of my room was another room overlooking it, and that guard watched over me and Eichmann. In the next room was the duty officer, who guarded over both of us.”

Food, Nagar related, was brought in in locked containers to prevent any attempt at poisoning by those who wanted to take revenge before the court’s verdict.

“Before I gave him his meal, I had to taste it myself to make sure it wasn’t poisoned,” Nagar shared. “If I didn’t drop dead after two minutes, the duty officer let the plate into his cell.”

He remembered how there were guards there who had numbers on their arms, but they were banned from the second floor.

“Before we were clear about this rule, one guard from downstairs, his name was Blumenfeld and he’d survived the camps, asked if he could switch with me one night,” Nagar related. “I assumed he just wanted to get a look at the man who murdered his family. Anyway, we were all in the same unit, so why not? But then Blumenfeld approached the door of Eichmann’s cell and rolled up his sleeve. ‘You see this?’ he sneered. ‘Once I was in your hands, and now the tables have turned. Look who has the last laugh!’ It was the middle of the night and Eichmann jumped up from his bed and started ranting in German. I, of course, couldn’t follow the conversation, but from then on, we had clear instructions — no switching or we’d get court-martialed.”

Eichmann’s daily schedule, Nagar remembered, was rigid, which was just fine for the Nazi mastermind who was the embodiment of efficiency and punctiliousness. Five a.m. was wakeup, washing, making the bed, shaving, tidying the room and the washroom; 7 a.m. was breakfast; 10 a.m. was a doctor’s checkup; 10:30 to 11 a.m. was a walk; 12 p.m. was lunch; 1-3 p.m. was afternoon rest; 3 to 3:30 p.m. was another walk; 6:30 p.m. was supper; 9:30 to 10 p.m. was washing up and going to sleep. If he couldn’t fall asleep, he was given a mild tranquilizer.

During Eichmann’s incarceration, his wife visited at least once. But all visitors, even his lawyer, could only communicate through a glass partition.

“During his free time,” Nagar said, “Eichmann would sit at a table and write. He was encouraged to write and was well-supplied with paper and quality pens. They thought maybe he would indict other Nazis in his memoirs, perhaps let some information slip. But he was careful. They couldn’t retrieve anything incriminating.”

Eichmann managed to hide out in Europe after the war until 1950, when he escaped to Argentina. He sent for his wife and children two years later. For years those whereabouts were a mystery, but in 1957 the Mossad got a tip that he was alive and living in Buenos Aires under an alias. And so, the hunt, which lasted four years, was on. Mossad leader Isser Harel was determined to capture, but not kill him — he wanted Eichmann brought to justice in front of the Jewish people.

The investigation, though, moved slowly. “The investigators could not risk the danger that their prey would learn he was being followed. Even more difficult was the necessity of identifying their man beyond the shadow of a doubt. The only thing worse than losing the real Eichmann would be capturing the wrong one,” Harel later wrote in his book, The House on Garibaldi Street.

But Eichmann had destroyed all evidence of his former identity. He even cut away the tattoo all SS men had under their left armpit. There were no fingerprints, just some blurry pictures from before the war. Then, two years into the investigation, the Israelis discovered that Eichmann had changed his name to Ricardo Klement, yet one son still used the original family name, and his trail led the agents to Garibaldi Street in Bueno Aires. For weeks they surveyed the house and the bespectacled man who lived there. They felt certain it was Eichmann, but they needed proof. The proof came on March 21, 1960, as Ricardo Klement walked toward his home with a bouquet of flowers, giving it to the woman at the door. March 21 was Eichmann’s silver wedding anniversary.

The Mossad flew into action. The kidnapping had to be perfectly planned, with no hint that over 30 Mossad operatives would be entering Argentina. As Harel well knew, Israel would be violating Argentinian sovereignty by kidnapping Eichmann and whisking him out of the country. The night of the kidnapping, two Mossad operatives parked their car on Eichmann’s block and began tinkering with the engine. Another car with other agents was parked behind. As Eichmann approached them coming off the bus from work, the agents pounced on him, gagged him, and bundled him off in one of the cars. Harel guessed correctly that his family would not report him missing in order not to reveal anything about his previous Nazi past. His family did call hospitals, but avoided the police. They also called their Nazi friends — dozens had taken refuge in Argentina — but no one helped. Instead, they scattered, fearing Israel’s long arm.

The Mossad had him, but now they had to get him out of the country without arousing suspicion. In order to get him on a plane, they dressed him in an El Al uniform, and, in a drugged stupor, led him onto the plane. His identity was supposedly that of an El Al employee who had suffered a head injury and was now sufficiently recuperated to be able to fly back home. One of their own agents was even hospitalized in order to procure the proper forms. True to his efficient, detail-oriented nature, Eichmann cooperated fully with his captors, even reminding them that they had forgotten to put on his airline jacket. “That will arouse suspicion,” Eichmann lectured them, groggy as he was, “for I will be conspicuously different from the other crew members who are fully dressed.”

Once imprisoned in Israel, Eichmann was initially dressed in the red prison clothes of those sentenced to death under the British Mandate. But the appropriateness of that was questioned as Etzel and Lechi Jewish underground captives were also dressed that way on their way to be hanged at the hands of the British. Even the ruling left understood that the murderer of millions didn’t deserve the association. So Eichmann was given regular clothing, including a pair of trademark checkered slippers that he wore until his death. Furthermore, it was decided that he would be executed at Ramle Prison, and not at the Russian Compound in Jerusalem, where there was still a gallows used to hang Jewish underground victims during the British Mandate.

“Eichmann didn’t show any signs of fear or make attempts at flattery,” retired Supreme Court justice Gavriel Bach told Mishpacha in a wide-ranging interview soon before he passed away in 2022 at age 94. In 1961, German-born Bach, who was a lawyer in the State Prosecutor’s office when Eichmann was seized, was appointed the second of the three prosecutors in the Eichmann trial. As the trial got underway and Israelis finally confronted the magnitude of the atrocities that had been buried deep in survivors’ souls for over 15 years, it was Gavriel Bach who took center stage, as he was put in charge of the entire pre trial investigation. He would also serve as the liaison between the arch-murderer and the outside.

Bach was a natural choice. He was fluent in German and had already proven himself as a top-notch jurist in several high-profile cases over the previous decade, including the famous Kastner trial of the 1950s, in which government employee and former Hungarian community leader Rudolf Kastner was accused of being a Nazi collaborator and judged for having “sold his soul to the devil.”

“Eichmann was a very regular-looking middle-aged man with nondescript glasses, always polite and always calm and collected,” Bach remembered. “When I would stand up, he too would rise from his chair and stand in silence. In fact, he stood in silence in front of anyone whom he saw as a figure of power or authority. Evil henchman that he was, he always remained the German gentleman. He was a very distinct product of a rigid and hierarchal society, and quickly internalized his status as a prisoner. He even asked permission if he wanted to leave over one of the three slices of bread he was served.”

Yet behind the benign-looking man was a monster. “The horrific documents I had to peruse made my hair stand on end over and over again,” Bach related, saying the material was so shocking that it gave him no peace for years to come. “Eichmann was the final authority in everything connected to the mass murders, scrupulously documented everything, and was guided by one principle: Not to leave one Jew alive.”

One of the documents Bach’s team analyzed was a detailed list of Jews who arrived in Auschwitz in 1942-1943. There were dates but instead of names, there were just lists of numbers that had been burned into the inmates’ arms. Bach suggested to his group that perhaps they could find survivors with those matching numbers in order to confirm the accuracy of the document, when a tall, strapping officer name Mickey Gilad stood up.

“He was a real Israeli Sabra. None of us knew anything about his past, or that his name had once been Goldman. But instead of speaking, he rolled up his sleeve and showed us his number. ‘I’m on the list. I came to Auschwitz in September 1943,’ he said. We all fell silent — and for the first time, this tough-as-nails officer began to talk. It turns out that Mickey was caught by an SS trooper who beat him with eighty blows, when fifty are enough to kill a person. Somehow, Mickey was still alive, and so the Nazi shrieked, ‘Let’s see if you can get up and walk!’ With herculean strength, the nearly dead fellow stood up and ran away.

“As hard as those 80 blows were, Mickey then shared what he called the ‘eighty- first blow’ (which became the title of a book he later wrote),” Bach continued. “When he came to Eretz Yisrael and began to relate what he’d been through, the derision and scorn he received was the most painful blow of all.”

Eichmann’s appeal to the Supreme Court, on the grounds that he was merely carrying out instructions of the Reich and had no personal interest in killing Jews, was rejected, as was his request for clemency. As the execution day drew near, the Prison Service approached several employees whose background indicated that they had no personal account with the Nazi. Someone had to carry out the sentence, and most of the guards were actually vying for the privilege.

“I was the only one who refused,” Nagar related. “But because so many wanted it, it became a real issue so they decided to hold a lottery. And guess what — it landed on me.”

For head warden Avraham Merchavi, it was a perfect choice. Nagar, a former paratrooper and decorated soldier, was an orphan in Yemen during World War II.

“But I wasn’t happy,” Nagar said. “I told Merchavi he should find someone else to do the job. Then he took me and several other guards and showed us footage of how the Nazis took innocent children and tore them to pieces, how they dismembered living victims and so many other shocking scenes. I was so shaken that I agreed to whatever had to be done.”

At the same time, a Holocaust survivor named Pinchas Zeklikovsky was summoned by the police for a special mission. Zeklikovsky, whose family was wiped out by the Nazis, worked in an oven factory in the Kiryat Arye industrial area of Petach Tikvah and was an expert oven builder. He was asked to build an oven the size of a man’s body that would reach 1,800 degrees Celsius. He worked on the oven in the factory, telling curious inquirers that it was a special order for a factory in Eilat that burned fish bones.

On the afternoon of May 31, 1962, after the other workers left, an army truck rolled into the oven factory and loaded on the oven. Under heavy guard, the oven made its way to Ramle Prison.

The world knew that Eichmann’s days were limited, but his hanging was made public only after the fact; all the preparations were done secretly, for fear of sabotage by Eichmann supporters. Streets around the prison were cordoned off for several blocks that afternoon. Even Shalom Nagar didn’t know it was to take place that day.

In fact, that very afternoon, Nagar was on 48-hour furlough. He was walking on the street with his wife and infant son in his Holon neighborhood when a police van screeched to a halt in front of him and pulled him inside. It was Merchavi, and Nagar knew immediately what this special invitation was about, but he did not like the idea of being “kidnapped” by his boss, especially in front of his wife, who would surely call the police.

“So the car made a quick reverse in order for me to be able to tell my wife that this was my commanding officer and that there was a shortage of personnel that day, and that I’d have to go back to work until late that night,” Nagar related. “When we arrived at Ramle Prison, they gave me a stretcher, some sheets and bandages, and told me to wait downstairs. Meanwhile, upstairs Eichmann was with the priest, and was given a glass of wine. By the time I was summoned upstairs, the noose was already around his neck and he was standing on a specially-made trap door which would open under him when I would pull the lever.”

According to an official account, there were supposedly two people who would pull the lever simultaneously, so neither would know for sure by whose hand Eichmann died. But Nagar says he knows nothing about that.

“I didn’t see anyone else there. It was just me and Eichmann. I was standing a few feet from him, and looked him straight in the eye. He refused to have his face covered, and didn’t resist when he was told to stand on the floor that would open under him. Then I pulled the lever and he fell, dangling by the rope.”

A full hour later, Nagar and Merchavi went downstairs to release the body. (“I wanted to make sure he was dead — I didn’t want him to suddenly wake up!” Nagar said.) A scaffold was built in order to reach him and take him off the gallows.

“Merchavi told me to climb the scaffold and lift him, and then he would loosen the rope. For years I had nightmares of those moments. Eichmann’s face was white as chalk, his eyes were bulging and his tongue was dangling out. The rope rubbed the skin off his neck and so his tongue and chest were covered with blood. I didn’t know that when a person is strangled all the air remains in his stomach, and when I lifted him, all the air that was inside came up and the most horrifying sound was released from his mouth — ‘baaaaa!’ I felt the Angel of Death had come to take me too. All the accumulated blood squirted onto my face and clothes. Finally, a few other guards arrived and we managed to get him onto the stretcher we had prepared earlier.

“We took him to the other side of the courtyard, where the oven was waiting. One of the guards, his name was Luchs and he had been in Auschwitz, was given the job of heating the oven, and he did so with relish. The oven was so hot it was impossible to get too close, so they built tracks in order for the stretcher to slide into it with a push from the back end. It was my job to push the stretcher into the oven, but I was trembling so much that the body kept rolling from side to side. Finally, around 4 a.m., I was able to push him in and we closed the doors.”

Nagar was slated to escort the ashes to the Jaffa port, where they would be disposed of somewhere in the Mediterranean Sea, but he was in such a state of trauma that Merchavi had him sent home with an escort. When his wife saw him spattered with blood, she became hysterical.

“She thought I was beaten up in a fight,” Nagar related. “I told her I had just hung Eichmann. She didn’t believe me. She said there is no blood at a hanging. I told her, ‘Wait until morning and you’ll hear the news.’”

In the wee hours of the morning, the ashes were removed from the oven and transported by police van to the port. Yaakov Bergal, who had a little restaurant on the beach and owned a small boat, was charged with carrying the ashes beyond Israel’s territorial waters, so as not to defile the Holy Land. He didn’t know what was inside the container until he returned to shore.

For an entire year, Nagar suffered panic attacks. “I was in the Paratroopers, the Border Police, I’d seen everything and was even wounded in the arm,” he said. “I was never afraid, but somehow this was different.”

The Prison Service sent him on a two-week vacation and then back to school to complete his high school equivalency exams. In the evenings he worked as the prison switchboard operator, but to get to his office he had to walk past Eichmann’s cell.

“I had two guards escort me every day,” he related. “Then the chevreh started to tease me. Here I was, a paratrooper and a bomb sapper, and I was afraid of a dead man without a weapon. It was embarrassing, so the next evening I decided to go myself. I sang an old Yemenite tune to drown out the fear, but as I passed his cell, I saw my shadow in the glass door. I thought his ghost was coming to get me, and I fell down the stairs.”

Shalom Nagar worked for the Prison Service for the next 26 years. After the 1967 Six-Day War, Nagar was transferred to the Military Compound in Chevron where he served as security officer and then prison administrator. It was during those years that Rabbi Moshe Levinger led a group of families back to Chevron, first to camp out for three years in the Military Compound and then, with government permission, to build a community in outlying Kiryat Arba. Nagar developed close ties with the religious, emunah-driven Chevron settlers and subsequently bought a plot of land in Kiryat Arba’s Givat Mamreh section, where he and his wife lived for several years. They moved back to Holon in 1994, where Ora Nagar could be close to her 95-year-old mother (she passed away a decade later at age 105).

In early 1986, just two months before Nagar retired from the Service, John Demjanjuk — accused of being Treblinka death camp’s Ivan the Terrible — was extradited from the US and incarcerated at Ramle Prison, where at the time Nagar was again stationed as a senior officer. Demjanjuk was sentenced to death and was on death row for five years, before the Supreme Court overturned the verdict and acquitted him for lack of conclusive evidence. Before the acquittal though, when hanging seemed imminent, Nagar received a midnight phone call. He was now living in Kiryat Arba and spending whatever free time he had learning Torah and strengthening his mitzvah observance.

“It was one of the prison officers,” he related. “They wanted to know if I could do a repeat performance on Demjanjuk. I said, ‘Look, now I’m religious, I’m older, and I’m still traumatized from the first one. Besides, it’s a mitzvah for everyone. I did my mitzvah already. Let someone else have a turn.’ In the end, Demjanjuk was sent back to the US so I was off the hook.”

Upon retiring from the Prison Service in 1986 at age 50, Nagar grew back his long-lost peyot and a beard, and, encouraged by Rabbi Amnon Yitzchak, entered the world of kollel “to make up for thirty years of lost time,” he said. He also became a certified shochet, and until recently, spent half his week learning and the other half shechting. For the past three decades, he’d spend the days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur shechting chickens for kapparos, and would often be called by Sephardi yeshivos around the country to slaughter sheep for special occasions.

Over six decades have passed since the Eichmann execution, yet despite the personal trauma, until the end of his life, Reb Shalom would say how he was given a great merit.

“Hashem commands us to wipe out Amalek, to ‘erase his memory from under the sky’ and ‘not to forget,’” he would say. “I’ve fulfilled both.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1039)

Oops! We could not locate your form.