Come to Light

| June 3, 2020A unique art exhibit showcased the magnificent creations of burgeoning chareidi artists, and helped them launch their careers

What makes an artist? Where is that fine line separating a person who paints as a hobby from one who’s a professional artist — and how does an aspiring artist manage to cross it?

On a sunny Sunday in late January, I head to Yerushalayim to tour a unique art exhibit showcasing the world of chareidi women, and explore the answer to this question.

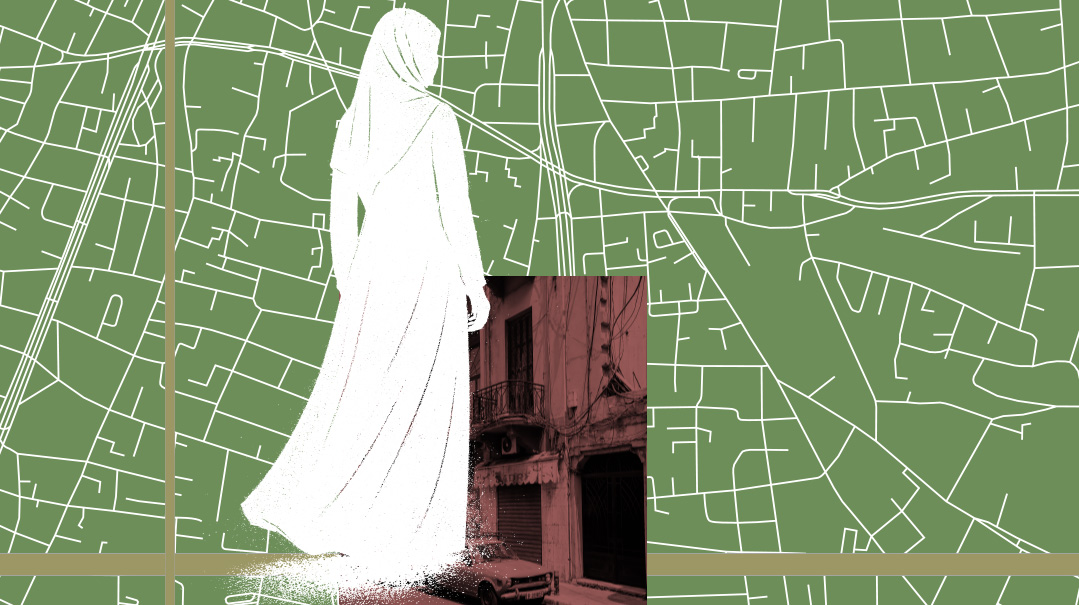

The name of the exhibit, Yotzrot La’Or is a play on the Hebrew term yotz’ot la’or, describing the female artists (yotzrot, or creators) who are now “coming to light” and gaining their first exposure to the wider public.

This theme is subtly conveyed in the exhibition room itself. It’s an unfinished open space with bare concrete walls, a rough concrete floor, and an unfinished ceiling with light bulbs strung across the exposed metal pipes. Yet the room is large and airy, with floor to ceiling glass panels on the exterior wall, letting in an abundance of natural sunlight and a view of the bustling Rechov Yaffo.

Suddenly, I get it. The curators have brilliantly used this transformed raw space as the perfect backdrop to highlight the entire purpose of this exhibit. Yotzrot La’Or… The goal of this exhibit, and of the organization behind it — Yotzrim Sviva, created by Michal Rozner to advance and promote chareidi female artists — is to help still-raw artists polish their professional skill to make themselves into a marketable, sellable entity.

More than Just Skill

The 30 featured artists, who were chosen after a rigorous selection process, range from those first getting their feet wet to those who’ve been engaged in art for years. (There are a couple of male chareidi artists featured as well.) They all have the talent and skill to hold their own among professional artists. Yet they also have another thing in common: They need guidance and a medium to help them reach a wider audience.

To become a professional artist, Michal explains, you need two important skills. First and foremost, you must reach a certain level of proficiency. And you do that the same way a musician gets to Carnegie Hall — with lots of practice. This means taking the natural talent Hashem gifted you with and polishing it with hundreds and thousands of hours working under expert teachers.

But while that investment of time and sweat might make you a professional-level artist, it still won’t make you a professional artist. To earn that vaunted title, you need one more ingredient: an audience interested in buying your work. And to connect with those magical people who love art and are willing to spend on it — not just any art, but your art — you need to know branding. Marketing. Publicity. How to find your audience, how to present yourself, how to connect with potential clients. In other words, all the business and marketing skills that don’t tend to go hand-in-hand with the creative, artistic personality.

To this end, Yotzrim Sviva offers courses, workshops, and professional guidance, showcasing its members’ work both on its own website — which features a constantly updated gallery — and in a unique journal of chareidi art. They also plan on setting up more group exhibitions with sale galleries like this one, allowing the artists to reduce prices by cutting out the middleman. The organization also benefits the general chareidi public with its activities — for example, during the coronavirus crisis, their artists have been preparing art projects and coloring sheets for children, and sending them out to families.

“I’ve loved art since I was born,” says Michal. Growing up in Bnei Brak, there weren’t so many opportunities to develop her talent; the art classes in school tended to be of the “now you draw a triangle for the roof and color it red” variety, designed to foster imitation, not creativity. As she described it, “We worked on the same embroidery the entire year. I don’t even know if I’d call it art.”

Still, she says, she was drawn to the visual arts and would comb through catalogues, pulling out pieces whose design caught her eye. Yet it was hard to find venues to learn art that were appropriate for a chareidi girl. After her marriage, she went to school to learn product design, but her childhood experience made her determined to provide the new generation of budding chareidi artists the opportunities that weren’t available to her.

“My own daughter, who’s 14, is very artistic. I want her to be able to develop her talents to the maximum, without sacrificing her values.”

What does this entail?

“First of all, they need a place to study, where they can be exposed to great art without having to worry about seeing inappropriate things.” Today, she says, this is much easier to find, as chareidi artists like herself are opening programs.

But learning art isn’t enough. “They also need a place to display their work that fits within their standards of tzniyus. Many of these women wouldn’t want to display their work in a mixed setting, especially if it’s alongside pieces that don’t match their values. That’s what we aimed to solve by creating this exhibit.”

Many Media, One Goal

Pessy Samson, one of the exhibiting artists, meets me to give me a tour of the exhibit. Originally from Australia, she currently runs an art school here in Israel, where she gives classes to girls and women, and also trains art teachers.

She has four of her own oil paintings on display, three of which depict scenes from Meah Shearim and Geula, and the last, a picture of the Kosel. All the pictures use vivid colors, built with several layers of paint, and give you a sense of vibrancy and motion.

“I love finding scenes that speak to me,” says Pessy, who explains that for these paintings she went to Geula, took pictures, then painted them. “I look for the energy in a scene, the story it tells. And the color — I love the color!”

We walk around the room, where there’s a wide variety of visual art media on display: photographs of nature scenes in Israel, wood cuts, paper cuts, print drawings, sculptures, and paintings. Among the paintings themselves, there are a range of genres: portraits of gedolim, street scenes, flowers and fruit, abstract.

She stops by a painting of a father and son, dressed in traditional Sephardi garb and learning together in an old-time Sephardi shul. Pessy points out how Susan Toledano, the artist, used a more basic color palette and simple shapes, reminiscent of folk art, in order to tell the old-world story taking place here.

“Does every piece of art tell a story?” I ask Pessy.

“It should,” she says. “Especially Jewish art. What makes our art Jewish is that we’re expressing our emotion about a life that’s beyond just ourselves.”

She adds that non-Jewish artists often need to feel pain and depression in order to access that meaningful part of themselves — which is evident in much of their work. However, contemporary Jewish art tends to be light and happy, even while it’s deep and meaningful.

Moving on, we come to an abstract painting of the Kosel by Haya Halifa, who has used a palette knife to create patterns and rhythms of bright blues, purples, pinks, and oranges in her Kosel stones. Much of art technique, Pessy says, involves understanding how to create balance — a balance of colors, a balance of dark and light, a balance of intensity — which the uninitiated art viewer may not be able to articulate as she looks at a painting, but subconsciously can appreciate.

“You should be able to look at a whole painting without one particular part jumping out at you, looking like it doesn’t fit,” she tells me. “For example, if you put a stroke of red in the middle, you could have reds elsewhere in the painting to balance it.” However, she adds, in this example, the surrounding reds shouldn’t be as intense as that middle stroke. “Every painting needs contrast, or the viewer’s eye isn’t drawn into it.”

As an example, she points to a painting by Riki Friedlander, another one of the exhibiting artists who’s busy setting up for an art workshop she’s about to give to a class of local high school girls. (Public viewing hours are in the late afternoon and evening.) Her vivid oil painting depicts a shul scene, filled with men in shtreimels, davening. While most of the men are in black, there’s also blue, yellow, and the occasional red caftan in the crowd. The red-garbed worshippers, Pessy shows me, appear in balanced intervals throughout the scene. The red is also picked up in the stained-glass windows at the top of the painting.

Riki tells me she was trained under the chareidi artist, Yossi Rosenstein. She learned from him to make painting a dynamic process: She’ll start off a piece with a basic idea of what she wants to draw, or the message she wants to express, but the painting often only takes on its full form as she works. She relates that all of her artwork is produced from her imagination, not from copying scenes or images.

Another one of her pieces on display is a dramatic picture of the walls of Yerushalayim, with brightly colored flames leaping up on either side and people standing in the middle, looking up at the walls. Riki calls this piece, which evokes breaking through the walls of Yerushalayim in 1967, Victory, and relates the story behind it.

One of her relatives was a soldier in the first unit to reach the Kosel during the Six Day War. They were coming down from the direction of the Har Habayis, walking through a narrow alleyway, and they saw the tops of the Kosel stones — but the only way forward was through a locked gate. Some of the soldiers found an old Arab, and her relative, who knew Arabic, asked him how to get to the Kosel. In answer, the trembling Arab pulled a large black key out of his pocket and said, “I came to show you the way.”

Riki’s relative followed him, leading the rest of his unit, and their guide brought them to a green door, stuck the key inside the lock, and turned it. They made their way down a winding staircase, and suddenly, there they were — standing before the Kosel.

“This story isn’t well-known,” she says, “but I love the imagery behind it — that each of us has a moment in our lives when we want to move forward, but feel there’s something blocking our way. All we need is to find that key, make that first opening, and then Hashem will help us.”

Riki goes back to setting up for the workshop, an example of a personal breakthrough in her own life. She tells me that giving classes is very new to her. “Being part of this exhibit has opened new doors for me. It’s given me the confidence to branch out professionally. Until now, I’d given some private lessons here and there, but never in a large group setting. By now, I’ve given several classes.”

New Horizons

From the exhibition hall, we head down one flight to the art gallery on the main floor of the building. This is an elegant, glass-front store featuring a variety of art products for sale, including paintings, special weave jewelry, mosaic art, gold leaf klaf Judaica. Among the overflow art displayed in the hall is a large rock sculpture, featuring rows of multi-colored rocks set in sand, which, according to Miri Chen, the exhibit’s marketing advisor, had been displayed in the Israel Museum.

“Most of these women are mothers of large families who, until now, were viewing their art as a hobby,” explains Miri. “A few of them have already reached a professional level and have sold some of their works, but most are at the beginning of the process. They’d love to be able to make a respectable parnassah from their ‘hobby.’ ”

As we’re speaking in the gallery, a woman walks in, whom Miri introduces me to as Dafna Avigayil Sufrin, the creator of the beautiful mosaic pieces featured in the gallery. This includes a hanging picture featuring an ocean scene made of mosaic tiles, stones, and beads, and a striking red-tiled chair and table displayed next to the entrance. The table features a mosaic chessboard.

“I call this the oldest Jewish art,” Dafna tells me. “The use of mosaics as art goes back thousands of years, where we find mosaic floors in our ancient shuls. In those days,” she adds, “everything was very measured, and each tile was a perfect square.” Today, in a nod to more modern art styles, she’ll use different shapes and sizes, with not every tile needing to be perfectly aligned.

As she shows me her work, she fills me in on her life story.

“My husband and I were part of the first wave of baalei teshuvah in Israel, in the Uri Zohar generation. We were both from North Tel Aviv; my husband learned at Ohr Somayach and I learned at Neve. I’d always enjoyed art, especially drawing, but once I became frum, I believed I needed to close off that side of me, that it wasn’t befitting a frum woman. Nowadays, we encourage baalei teshuvah to integrate their talents into a frum lifestyle. But in those days, things were different.”

So she said goodbye to her artistic pursuits, and instead threw herself into her new life, joining a frum community and raising her children and grandchildren. While it was hard for her to close off a part of her personality, in other ways, she says, integration into her chareidi community was much easier than anticipated.

“They’ve always accepted me as I am,” she says, indicating her artistic head wrap and dangling earrings. Still, art was bubbling beneath the surface — until five years ago, when she started working with mosaics.

“I’ve always dreamed of doing mosaic art. Though it’s just as much construction work as art!” she laughs. “Before you get to the pretty part, you’re breaking pieces and chiseling them.”

She was enjoying herself, but she saw this as just an outlet — until her friends began encouraging her to take it further.

“They told me, ‘You’re an artist! You can be a professional!’ ”

Avigayil is visibly emotional as she says, “Now I have it all! I’ve learned that I’m allowed to be a frum Jew, a mother, a grandmother — and also an artist!”

Building Bridges

Back upstairs in the exhibition hall, Riki Friedlander’s workshop is already underway. As I watch the high school girls painting their wooden boards, I observe that some are quietly focused on their work, while the majority are looking at what their friends are doing and adjusting their own artwork accordingly.

Pessy Samson, standing next to me, comments that teenagers are one of the hardest groups to teach art to, because they’ve already had their ability to self-express quashed. She tells me that her own students start from as young as four years old — and she especially loves teaching them at such an impressionable age.

“I like to reach them before they’ve been trained to just copy whatever the teacher does without thinking on their own about what they’re trying to draw,” she says, adding that she feels art education at the elementary school level is often too in-the-box. “They’re taught, ‘This is the way you must draw a table: by making a rectangle and four legs.’ I teach them to actually look at the table in front of them and draw what they see, not what they think it should be.”

With the four-to-six-year-old crowd, she’ll start with guided drawing and explanation of the processes: We can use these colors because these are the hues you see when you look at grass. But once they’re over six, she weans them off of this. And she trains teachers to do the same.

“I don’t let my teachers do anything on the students’ artwork. You need to give them confidence that they can produce their own art, not that they need something else in the picture to make it look pretty or perfect.”

She admits that sometimes it’s hard to refrain from correcting them, when you know that adding a brush of color here, or fixing a line there, would make such an improvement. “Instead, I’ll ask them, ‘Do you think it needs more color here, or more contrast?’ But if they say no, it’s okay the way it us, then I’ll stop. This needs to be their own work, something that has meaning for them.”

I ask a question I’ve always wondered about: Can anyone learn the skills to become an artist, or do you need to be born with natural talent?

“Art is a skill,” she replies. “As long as you have very good teachers who teach you the correct process and the perseverance to practice and get better, I believe anyone can find the joy and beauty in knowing how to create their own unique artwork.”

But even for those who haven’t been trained in the skill of creating art, appreciating it is something that’s open to everyone. As public reactions to this exhibit have demonstrated, art, in its function of transforming a private experience into a universal one, can serve as a bridge between different societal groups.

“We’ve had people coming to view the exhibit from all different sectors,” says Miri. “Many of the chilonim, in particular, were very impressed. Some of them told me that this was their first glimpse into the rich inner world of chareidi society. As one woman put it, after being constantly told by the media what the chareidim aren’t — they don’t work, they don’t serve in the army — coming here, she finally started to understand what they are.”

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 695)

Oops! We could not locate your form.