Caved In

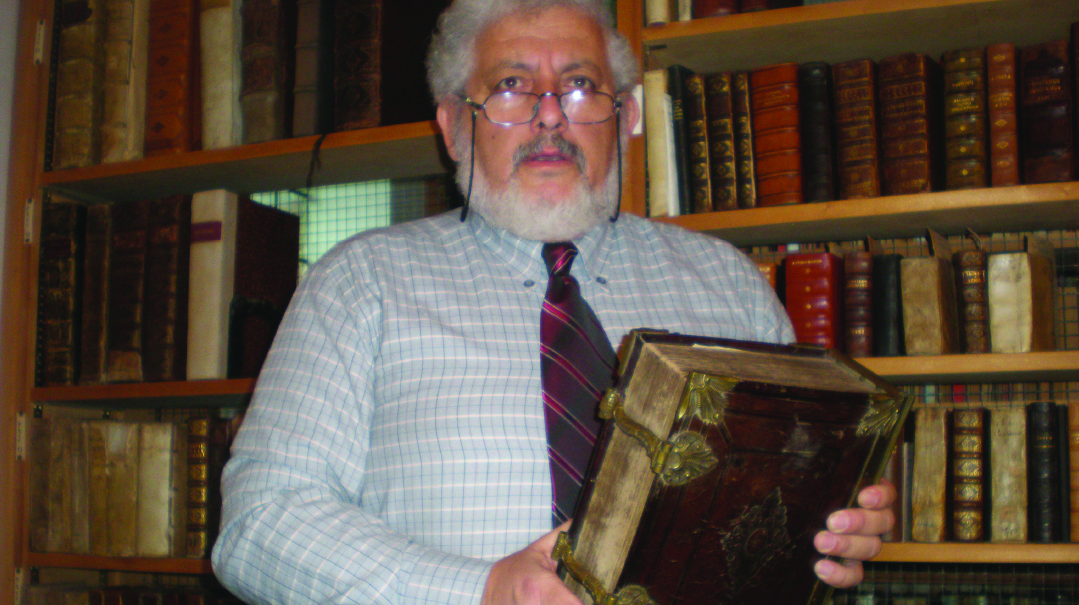

| April 7, 2021For over 25 years, renowned manuscript sleuth Moshe Rosenfeld has been traveling around the world in an effort to find and redeem ancient Jewish seforim

Photos: Elchanan Kotler

The Most Unlikely Places

For over 25 years, renowned manuscript sleuth Moshe Rosenfeld has been traveling around the world in an effort to find and redeem ancient Jewish seforim. He’s rummaged through attics and cellars in remote locations where Jews lived in the past. He’s climbed up the Himalayas and reached the slopes of the Andes Mountains. He’s traveled across America and Europe, South Africa and Russia. And he’s managed to gain access to convents and monasteries — even closely guarded sections of the Vatican library — in his ongoing efforts to redeem manuscripts and sifrei kodesh.

“Once,” Rosenfeld relates, “as I was exploring a library in a remote convent, I climbed a ladder to look on the upper shelves, which no one had touched for decades, maybe centuries. Suddenly, I found something amazing — an ancient tiny Tehillim from the 16th century. It wasn’t more than a centimeter tall.

One of his most surprising finds was in a convent, where he came across a Mishnayos with the stamp of Nazi official Hermann Goering. Goering, an art aficionado, built a well-known, massive collection by plundering pieces from Jewish owners who were deported to their deaths in Nazi camps. At the end of the war, Goering’s personal collection included 1,375 paintings, many sculptures, carpets, furniture, and other artifacts. But what many don’t know is that he also looted libraries and private collections in order to establish a Jewish library for research purposes. In a maneuver whose details he won’t discuss, Rosenfeld brought the seforim he found to Israel.

Keeping It Secret

Rosenfeld, of course, declines to expound on some of these trips, and when he does reveal information about his travels, he’s careful to omit many identifying details. One rescue mission that was publicized involved the transfer of a Jewish library established by Nazi henchman Adolf Eichmann.

“Like Goering, Eichmann collected thousands of Jewish seforim with the goal of establishing a Jewish library,” he relates. “The seforim were stored in Prague, and they remained there after the Holocaust, locked in storage rooms despite Jewish demands over the years to return them. After many diplomatic efforts, the Czech government in 1994 agreed to transfer most of the seforim to Jewish hands.”

Rosenfeld was asked by a friend to supervise the transfer. The seforim were sent to Israel via diplomatic mail, and each shipment included 14 cases of books. Ultimately, they arrived at a library in the Gush Etzion town of Alon Shvut, where they remain to this day.

Rosenfeld — or simply Moishe, as he insists on being called — is an expert in seforim, manuscripts, and Judaica. Twenty-five years ago, he and his friend and associate, Yeshayahu Winograd (who passed away this past year) established the Institute for Computerized Bibliography. Their innovation, known in Hebrew as Otzar Hasefer Ha’ivri Hamemuchshav, is used by central libraries and research institutes all over the world.

Tied into the Taliban

While Rosenfeld has found important works in the most unlikely places, he says the most exciting discovery he’s made is what has become known as the Afghanistan Genizah. For security reasons, this treasure trove hasn’t gotten much publicity, and many of the details of the find still remain classified.

In the spring of 1998, after a lecture Rosenfeld delivered about genizah collections and manuscripts, someone was waiting for him outside the hall. The man, who identified himself as Mr. Pozeiloff, asked Rosenfeld to come with him to a private corner so they could speak. Rosenfeld had no idea that this would launch one of the most fascinating and dangerous adventures of his life.

Pozeiloff introduced himself as a diamond dealer from Dallas, Texas, who had come to Eretz Yisrael for Pesach.

“A week ago,” he told Rosenfeld, “a resident of Afghanistan came into my store. He offered to sell me Jewish ancient texts on pieces of parchment, so I want to know what you think.”

Pozeiloff showed Rosenfeld a photocopy of one of the parchments that the Afghan had offered him.

“I realized that this was a piece of a very ancient manuscript,” Rosenfeld relates. “Without thinking too much, I said to him, ‘Buy it now, don’t wait.’ ”

Pozeiloff said he preferred to wait until after Pesach because he was then vacationing with his family, but Rosenfeld didn’t wait — he hurried to a manuscript expert for an opinion.

“It’s writing from the tenth century, and perhaps even earlier,” the expert told him. “This is priceless. Do everything you can to get it.”

Right after Pesach, Rosenfeld began planning his trip to Afghanistan.

“I’m not the type to sit and pore over photographs of manuscripts that everyone has already seen and researched,” he says. “Pursuing rare manuscripts is my daily fare, even in dangerous territory.”

The diamond dealer, meanwhile, managed to contact the Afghani, who identified himself as Abdallah. He connected the American with Ahmadzai — the head of the tribe that ruled the area, and they agreed to meet on May 28, 1998, at the Paris Peace Conference. Ahmadzai would bring a suitcase of manuscripts with him.

But the meeting never happened. The Taliban rulers had a tight hold on the piece of land where the Jewish manuscripts were hidden, and over the next year, meetings were arranged and canceled, sometimes ahead of time and sometimes at the last minute. One time, Rosenfeld was already waiting at the appointed place, but without warning, he was informed that the location of the meeting had been changed to a different country. He rushed to the airport to get to the new place, only to be disappointed yet again, when he was contacted and told that the meeting was canceled.

In June 1855, Afghanistan suffered a major earthquake, with dead and injured lying in the streets. Due to the catastrophic situation, the Afghanis reached out to Rosenfeld through the diamond dealer, offering the suitcase of manuscripts in exchange for a planeload of corn and wheat. At the time, there was a terrible famine in Afghanistan, and despite American aid, the country was desperate for more food.

Rosenfeld consulted a few friends who worked in Israel’s security agencies, and after speaking with their superiors, the Israelis agreed to the deal. Rosenfeld advised the diamond dealer to go ahead with it, even though he had no idea how he would obtain a plane full of grain.

But then the Taliban took over the country and all contact was cut off. A month later though, the first signs of life emerged from the caves of Afghanistan. They renewed ties with Pozeiloff, but demanded an astronomical sum of money in exchange. Pozeiloff initially refused. But then he suggested to Rosenfeld that they go to the Be’er Yaakov of Nadvorna ztz”l, who, until his passing in 2012, was sought after by chassidim and businessmen alike for his uncanny wisdom and advice.

“We traveled to Bnei Brak to the Rebbe’s home,” Rosenfeld relates.

They gave the Rebbe all the details, including the risks and political intrigue surrounding the manuscript rescue. The Rebbe considered, instructed Pozeiloff to join Rosenfeld’s efforts, and then gave them both a brachah. Before they left the Rebbe’s room, the Rebbe asked Rosenfeld to come and visit again. From that point on, Rosenfeld has maintained ties to the court of Nadvorna, and after the Rebbe’s passing, continues to visit his son, the current rebbe of Nadvorna–Bnei Brak.

A few months later, Pozeiloff decided to withdraw from the effort for personal reasons, and left Rosenfeld the contact information and a map of the location of the cave that the Afghani had sent him. Rosenfeld decided to take the risk of traveling alone to the mountains and deserts of Afghanistan. Before embarking on such a precarious trip, though, he asked a friend in the security services for an exact overview of what was going on in the region.

The next day, there was a detailed report on his desk, with a warning from his friend: “Call it off — too dangerous.”

Rosenfeld canceled the trip and decided to work through other channels. Toward that end, he joined up with friends Yisrael Shai and Tuvia Livneh, both former members of the security services. After extensive planning, Shai traveled to Tajikistan, near Pakistan, to meet with a senior leader in the area, who agreed, for a small fee, to activate his people to confirm the existence of the cave.

A few days later, and the contact from Afghanistan called. This time, he was ready to transfer the manuscripts, but in exchange he wanted a plane filled not with corn, but with weapons for the rebels. Shai and Livneh weren’t getting involved in rebel insurgency, and the agreement was taken off the table.

Contact with the Enemy

But that wasn’t the end of the story.

“In 1855, we received information that in Sweden, there was a community of Afghani refugees, some of whom came from the region we were focused on,” Rosenfeld relates. “So we traveled to meet them, and at the same time, we reached out to some human-rights activists who had ties in Afghanistan and corroborated information about the location we were trying to get to.”

With new information in their hands, Rosenfeld decided to travel with his friend and colleague Yeshayahu Winograd to the Afghani border and set up a meeting in the wild, mountainous region of the Afghanistan-Uzbekistan border.

“If you have material and pictures,” Rosenfeld told them before embarking on the trip, “we’ll meet at the border, set up a price, and travel to Europe to transfer the materials.”

At the time, a senior Afghan official came to Israel to coordinate the transfer with Israel’s security services. Rosenfeld met with him, but while he was willing to give over “valuable information,” as Rosenfeld says, again there was foot-dragging. At this point, Rosenfeld lost his patience. He felt like he was going in circles but not getting nearer to his goal.

“Dealing with Arabs takes a long time,” Yisrael Shai explained to him. “Every step brings us closer to the entrance of the cave, but we have to maintain restraint.”

In the summer of 2000, the original Afghan contact reached out again, and set a very surprising place to meet: the United States. It was a difficult decision. Meeting in America with Taliban people — who were classified as terrorists at that point — could be a federal crime.

It was decided that Tuvia Livneh would travel alone to the meeting, but while waiting for the flight, he received a warning: “Your Afghan friends are being followed by American security services because they are suspected of belonging to a terrorist organization. If you meet them, you might be arrested for being in contact with the enemy.”

Obviously, he turned back and reported to Rosenfeld.

After the American meeting didn’t happen, the Taliban suggested that they meet in London, at the Hilton Kensington. This time, it was decided not to repeat the mistake that almost led to a diplomatic dustup with the United States. The meeting was coordinated with the British security services. Indeed, when the day came, there were armed guards in the hotel, and the three bearded visitors from Afghanistan were clearly nervous. The last thing they wanted was for someone to connect them to Osama bin Laden’s terror group.

“I’m Rahimi,” the leader of the trio addressed his Jewish partners, Moshe Rosenfeld and Yisrael Shai. “In northern Afghanistan there is a cave,” he said, naming the area. “It belongs to us, the Ahmadzai family. Inside there is a big treasure of Jewish manuscripts.” The Afghani sat up straighter and looked directly at the Jews sitting across from him. “Currently, the cave is sealed and camouflaged and no one knows of its existence. If you are pleased with this manuscript that we brought you, we can proceed.”

With a rough motion, he placed a small wooden box on the table. Rosenfeld leaned toward the table and carefully picked up the box. He opened it with trembling hands to find what he assumed to be the oldest existing siddur in the world.

“If you’re so open about your emotions,” Shai whispered under his breath, “it’s gonna cost us.”

Rosenfeld composed himself, casually leafing through the priceless siddur, and noticed there was a Haggadah shel Pesach printed inside, as well as a poem about the vision of the End of Days.

The siddur was the hook, but it didn’t yet belong to him. It was hard for him to come to terms with having to return it to the unholy hands of Afghanis, who might be Taliban terrorists. He asked permission of the Afghanis to photograph a few of the pages in order to further examine them, immediately sending the photocopies to his friend, Professor Eliezer Horowitz, who warned him to take the siddur at any price. Rosenfeld gave the siddur back to the Afghanis, consoling himself that in the near future, he would be able to return it to Jewish hands.

Then the exhausting negotiations began, and ultimately, they reached an agreement. They also agreed to meet at the same place five days later. The date that they set was none other than September 11, 2001. The Afghanis promised to bring more Jewish manuscripts with them as part of the deal. Rosenfeld, for his part, never dreamed it would be the last time he held that siddur.

Five days later, when Rosenfeld, Shai, and Yeshayahu Winograd landed at Heathrow Airport for the acquisition of their life, the world turned dark. The Twin Towers had been toppled in a terrorist attack.

An accusing finger was pointed at the Taliban terror organization that had given refuge to al-Qaeda and archterrorist Osama bin Laden. Rosenfeld felt his blood freeze in his veins; he knew exactly what this meant. He and Yisrael Shai quickly called the Afghanis, but as he suspected, no one answered. They hurried to the place where the Afghans were staying, but the three had disappeared without a trace, taking all the valuables with them.

From that point on, any connection with the terror group became an international crime. Obviously, the Afghanis did not dare make contact, especially since the Taliban became embroiled in a guerilla war with the United States. The fate of the siddur, and of the rest of the priceless manuscripts, was murky — stashed away in caves used as Taliban hideouts. Every so often, Rosenfeld heard about a dealer who had somehow gotten hold of it, but all his efforts to track it down led nowhere.

But it didn’t end there, and in fact, there’s a happy ending to the story. In 2013, researchers were given access to the caves and discovered a trove of rare Afghan-Jewish documents dating from the 11th to 13th centuries. The documents ranged from letters and articles related to family business to copies of religious and biblical texts. At first, the National Library of Israel was able to purchase 29 of these documents, and in 2016, the Library was able to purchase another 250 of these medieval Afghan texts, including the siddur that Moshe Rosenfeld feared he’d never see again.

Crown Jewel

Rosenfeld, however, doesn’t only deal in redeeming seforim. He’s also been involved in redeeming possessions left behind by Jews who perished in the furnaces of Europe.

During the course of his investigations, Rosenfeld reached the village of Ober-Wisho in the Marmarosh-Sighet district of Romania and the beis medrash of the Vishive Rebbe, Rav Menachem Mendel Hager, eldest son of the Ahavas Yisrael of Vizhnitz. In conversation with the villagers, he learned that the gentile who lived across from the shul had taken possession of the famed crown from the aron kodesh, which was plated in gold.

To Rosenfeld, it was clear that he had to redeem that crown at all costs. When he asked the local resident to

show it to him, the latter agreed. Rosenfeld was floored by its beauty and size. In exchange for a small sum, Rosenfeld purchased the crown, and asked for a large piece of fabric and a rope. When he left the man’s house, Rosenfeld realized he had a big problem. The crown was very large, and because it was classified as a Judaica item, he could not get it out of Romania simply by carrying it through customs. He loaded it into his car and set out through the Carpathian Mountains, planning to hide it until he would find a way to bring it to Israel.

As he passed through a forest, he had an idea. He turned off the road and searched for a large tree. When he found was he was looking for, he took the crown out of the car, covered it with the fabric, tied it well with the rope, and hoisted it into the tree, hiding it well between the branches. With the intervention of Israel’s Foreign Ministry, the crown was transferred to the Israeli embassy in Romania, and then sent by diplomatic post to Israel.

Wheels of Fortune

Another time, he traveled with a friend to the cemetery near the Hungarian border. Curiously, he glanced into the taharah room. To his surprise, he saw that the interior of the room was taken up by a carriage that was used to carry the bodies of the deceased to the cemetery. He began to think of how such a contraption could be brought to Israel.

The problem was how to cross the border into Hungary without arousing suspicion. He examined the carriage further, discovering a Magen David symbol on each side. He took off the Jewish symbols and dragged it outside.

He went with his friend to a home nearby where a non-Jewish farmer lived. There was a horse in the yard, and Rosenfeld’s friend, who spoke Hungarian, explained to the gentile that this carriage had belonged to his grandfather, but because he had no horse, he wanted to hook up the old carriage to the horse and bring it to Hungary, which was just a kilometer from the village, where someone would be waiting for him. Rosenfeld’s friend took a bill out of his pocket and tore it in half. He gave the farmer half the bill, and promised that he would get the other half when he brought the carriage to Hungary. After the carriage arrived in Hungary, it was taken apart and sent to Israel, where it was restored and placed in the Israel Museum for preservation.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 855)

Oops! We could not locate your form.