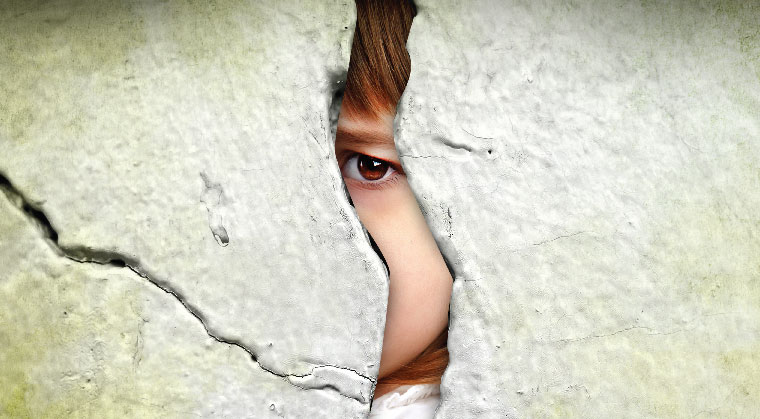

Before It’s Too Late

At-risk behaviors of teenage girls don’t usually start in adolescence, but often have their roots in the stresses and anxieties of elementary school, making early intervention fundamental to changing the trajectory of this disturbing trend.

It’s an early Sunday morning and Torah Umesorah’s Brooklyn office is packed with women carrying notebooks and pens. These hand-picked teachers chosen by their Bais Yaakov elementary schools are forgoing the weekend pleasures of making pancakes and reading the paper over a mug of coffee in order to participate in a training program that will help them identify potential problems within their student body — before those problems spin out of control.

Following in the path of Torah Umesorah’s highly successful Mashgiach program, introduced into US and Canadian yeshivos in September 2014 to help stem the tide of at-risk kids, this new Mechanechet program is designed to provide every girl — not the ones who wear their problems on their sleeves but all young girls, even those who are well-adjusted and flourishing — with a safe place in which to discuss anything that might come up.

“Our goal is for every school to have a trained individual whose job is to reach out and develop a special kesher with students. We are giving these educators a paraprofessional background in psychology, empathy training, and communication in order to enable them to connect more effectively with their students,” says Rabbi Dovid Morgenstern, director of the Mashgiach and Mechanechet training programs, who’s currently working with 18 elementary schools in the Bais Yaakov system. “The women are out there as the first line of defense, making healthy connections with these young girls who know their confidences will be respected.”

This is just one of several initiatives aimed at helping “regular” girls successfully navigate the challenges of growing up, as many face demoralizing academic pressures and today’s changing family dynamics which often strip kids of necessary nurturing time.

At first glance, the enterprise might look like regular guidance counselor training. And why put effort into fixing something that isn’t broken in the first place? Yet according to Rabbi Yoel Kramer — former principal of Bnos Leah Prospect Park Yeshiva who currently works for Torah Umesorah’s Yaldei Yisroel School Placement program, which finds appropriate schools for girls displaced from their local Bais Yaakovs – a lot more can be done in elementary schools to nip the problem of teens at risk in the bud.

Rabbi Kramer says that early intervention is critical to changing the trajectory of this disturbing trend, and the shift toward targeting elementary-aged students by giving them the tools they need to withstand undue influences and better face life’s inevitable challenges is a blessing.

Attention deficit disorder, serious behavioral and emotional problems like Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, eating disorders, depression and anxiety, as well as coping with divorce, death in the family, or financial stress are some of the areas mechanchos learn to handle, as they get into the nitty-gritty of working with girls dealing with the realities of life in a tough world.

“The earlier you identify a problem, the better the prognosis,” says Dr. David Pelcovitz, professor of Psychology and Education at Yeshiva University and considered one of today’s most important child advocates. “Once you understand and identify the symptoms of stress and abuse in a child, which present much differently than in an adult, you are then able to intervene — before it morphs into something more serious.”

Dr. Pelcovitz believes that early intervention on the elementary school level can save a girl from experiencing recurrent episodes of depression or anxiety throughout her life. “Bullying or problems related to social or parental issues can directly impact these girls’ bein adam l’Makom issues later on, and if we can help them manage their anxiety at this stage, it will make an enormous difference.”

Look in the Mirror

But not every problem is easily identified and children often fall through the cracks, according to psychologist Dr. Zev Brown, one of the trainers in the Mechanechet program who sees the initiative as filling an educational void. “When a student does well academically and socially and suddenly she misbehaves, the school may treat it as a disciplinary issue,” he says. “The Mechanechet would, rather, take the child aside, spend time with her and hopefully she will open up about what is really going on.” The Mechanechet, he emphasizes, is not a therapist, but a channel for opening up a line of communication with the child.

Not all those problems are of crisis proportions though, says Esther Spira,* principal of a chassidic girls’ school in Monsey who has assigned two teachers to the position of Mechanechet, occasionally even accompanying them to the weekly sessions. (“That way I could find out what they were learning and together we could determine how to apply this information in practical ways into our school.”) One major stressor, she says, is that much more is expected of students today — whether academically or socially — than ever before. If girls used to be able to get away with doing the minimum as long as they didn’t make trouble, that’s no longer how it works. Today’s teachers demand a lot more, and subsequently, anxiety levels among students have shot up.

“But we can only push them if we understand them and continually assess them as they go along,” says Mrs. Spira. “Our ultimate goal is to create a safe place for the child; a place where she feels valued, thrives, and grows.”

Another factor that should be acknowledged, she says, is that the neediness girls are exhibiting can be at least partially attributed to today’s extremely busy households.

“Both parents are working. Mothers are so overwhelmed that they are barely able to catch their breaths. The children, in turn, trust their teachers to provide them with the care, understanding , and help they might not be getting at home. And teachers must live up to that trust. I tell my teachers, ‘You’re often like the mother here.’ ”

She’s not alone in this assessment. Communal benefactor Reb Yaakov Adler,* who together with a group of like-minded askanim are personally sponsoring a number of initiatives tackling what they believe are some of the primary challenges facing today’s Bais Yaakov girls, says much of what ails the system is our own inability to see what our homes really look like.

“We must look at ourselves in the mirror. What are we doing wrong? Are we home with our children? Or are we out most evenings and Shabbos attending simchahs and kiddushim? When at home, are we constantly on the cell talking to friends? As parents, our children must be our number one priority, and as a community, our number-one focus must be on saving the next generation.”

Working under the guidance of Rav Eli Ber Wachtfogel, Rav Eli Brudny, and Rav Yaakov Bender, the group successfully coordinated the adoption and enforcement of policies pertaining to the Internet and cell phone use in 16 elementary and 10 high schools in the Brooklyn area. Elementary-aged girls attending those schools are now prohibited from owning their own phones as well as using any unfiltered phones, including their parents’ phones; all homes must filter their Internet; cameras are off-limits in schools; and teachers must restrict their own cell use to the office and teachers’ lounge. In the high schools, ninth and tenth graders may not own even filtered cells, and as far as grades 11 and 12 are concerned, individual schools are defining their use. One high school principal told Mishpacha that handling the issue in elementary school goes a long way toward easing its enforcement in high school.

“We are not punishing the girls. We are teaching them why a bas Yisrael is different than the rest of the world. It’s not just that girls go online and are exposed to the wrong things; but, through these distractions, they no longer focus on their yiras Shamayim, school work, and on building healthy relationships with friends, which many admit have been severely damaged,” the principal said.

I’m Not Judging You

Another group of forward thinking askanim, along similar lines, has put together a budget to hire Suri Rubin, the gifted Bais Yaakov High School of Boro Park guidance counselor, to work with principals, teachers, and students in a number of other Bais Yaakov high schools in the Brooklyn area.

Although Mrs. Rubin’s focus is on adolescents, she agrees that early intervention is vital — and can often prevent the fallout she deals with at the later stage. “What we can accomplish in high schools is big, but what transpires in elementary schools is crucial,” she says. “When the children are young and innocent, their situation is much clearer. When they become teens, their problems are aggravated by hormones, anger, and other issues.”

Mrs. Rubin speaks from professional experience. For five years, she’s run Achoseinu, a mentoring program that pairs twelfth graders with struggling elementary school girls in a confidential, nonjudgmental big sister/little sister relationship. When she started, much of the training took place around Mrs. Rubin’s own dining room table, where the girls would discuss how to deal with all sorts of issues that crop up in troubled families — like poor hygiene, for example.

The dynamic of the mechanechet, though, is a bit different from the big sister/little sister relationship, primarily because she’s not only a confidante, but an authority figure as well.

“The key to the success of any mechanechet is gaining the trust of the girls,” says Suri Rubin, who admits that once girls reach high school age with baggage, the situation becomes more complex, as acting out and issues of rebellion take center stage. “I tell my girls, ‘I’m not kicking you out of school. I’m not judging you. You can share whatever’s going on. Here you aren’t getting into trouble.’ ”

A girl’s decision not to keep Shabbos and other mitzvos, Mrs. Rubin found, is rarely hashkafically based but often centers on issues of self-worth and a need to feel unconstrained, which may or may not be home related. If there was abuse, “they can’t deal with stress, can’t deal with ‘no.’ They feel, ‘I just need to be free now.’ I tell them, if you are comfortable in your own skin, keeping Shabbos and other mitzvos will automatically come to you.”

Do some simply find Shabbos boring? “There is no question that girls have been impacted by our fast-paced technological society, and some of these girls just don’t have the inner resources needed to slow down. Parents have to teach their children when they’re young how to entertain themselves and how to alleviate boredom with healthy alternatives.”

Parents often blame bad friends for their daughter’s behavior, believing that if only she were separated from so-and-so, all would be well. But according to Mrs. Rubin, it’s not that simple. There is a reason why a girl is attracted to another, even if that girl isn’t a real friend and doesn’t have her best interests at heart.

“Many girls find themselves trapped in bad relationships because they don’t know what a real friend is,” says Mrs. Rubin. But once she learns about her own self-worth, she can then ask herself, “Why am I calling her a best friend? Why do I feel so close to her? What do I enjoy in her?”

Adolescent girls are often confused and angry; there are pressures from school and from home, whether financial, shidduchim related or, in some cases, due to dysfunctional or overly controlling or manipulative parenting. Insecurity, low self-esteem — these issues even plague valedictorians and G O presidents. Every girl has her own reasons for feeling insecure. For some, their expectations of self are so high that they feel they can never attain them. Others might feel they can never measure up to other people’s expectations of them, while some girls simply don’t like themselves and believe nobody else does either. “We need to give our children a lot of warmth, love, and acceptance for who they are early on,” says Mrs. Rubin. That way, they are armed with an internally healthier core to better withstand adolescent pressures.

Whatever’s in their Hearts

A few states over in Cleveland, community activists Murray and Malka Leah Kovel were deeply dismayed by the number of frum children who were not being reached through traditional means. Missing from the equation, they believed, was early intervention enrichment programming to help children stay the course religiously.

“Today’s schools don’t have much time to teach children about emotional or hashkafic issues, especially at the elementary school age when so much factual information is being conveyed,” Malka Leah says. So they set about filling that void. Their brainchild, Atideinu, helps fourth-, fifth- and sixth-grade boys and girls (they meet separately) develop the skills to identify and articulate their often confused feelings and inner needs, and to withstand negative peer pressure. Developing these skills in early childhood, Malka Leah says, will help them overcome the challenges they will inevitably face in their teens. Atideinu’s curriculum — developed by a clinical social worker who also runs the program — works on promoting emotional intelligence, self-advocacy and self-management. “What does it mean to be hungry? To be angry? To be frightened? How does it feel inside? Once they’re more aware of what’s going on within them, they can control their emotions better.”

Most of the children in the group are referred by principals and teachers, and they come with a variety of challenges. What they find is an open, supportive environment where they can discuss whatever is in their hearts. “Whether its divorce or having to compete with special-needs siblings for their parents’ attention, they are completely comfortable talking it out.”

Even though they are young, much time is spent working on their relationship with G-d, using the Jewish calendar to highlight spiritual themes, such as trusting in G-d when circumstances seem dark, and how to find the light hidden within the darkness.

The idea, says Malka Leah, is that even if a girl sees herself as very fragile, if she can tap into the spiritual resources Hashem has given her and learns to trust in Hashem and in others, she can create a safe place for herself, know that she is intrinsically strong, and not break in the face of conflict or trauma.

“Children who were shy and uncertain when they started attending are now taking the tools they are given back into the classroom and teaching these tools to their classmates,” says Mrs. Kovel. “These girls who no one paid much attention to before are now becoming class leaders.”

When the Chips are Down

By now we all know that healthy self-esteem is one major factor for a child’s emotional health, but how can parents and teachers build self-esteem in their children? Suri Rubin refers to master educator and motivational speaker Rick Lavoie’s well-known “poker chip” analogy. According to Lavoie, all of us have a stack of poker chips in front of us, some with dozens of tall stacks and others with just one or two piles that they don’t want to risk. Every morning our children wake up and take their stack of chips with them to the breakfast table, the school bus, the classroom. He might have had a nice stack first thing in the morning, but a sibling insult diminished his stack, a fight on the bus took away a few more, and a push by the class bully just about decimated his stack. Then the teacher poses a question to the class, but he can’t risk a wrong answer and the loss of even more chips, so he doesn’t raise his hand. The answer turns out to be the one he knew, a chance to rebuild his stack — but he just couldn’t take the risk.

Self-esteem, Lavoie explains, is like your stack of poker chips. When good things happen to you, you get more poker chips. The popular kids have huge stacks, while the learning challenged don’t have much — and certainly not enough to gamble away, holding onto what they do have with desperation. But kids experience both good and bad things all day long, so how can those chips be constantly resupplied? Go to bat for your kids, says Lavoie in his popular workshops and speeches. There are going to be many people in your child’s life that take away chips, and so you need to be his advocate and help him get more chips. You need to be a talent scout and emphasize the things he/she does well, so that by the day’s end, your child has more poker chips than he started out with.

“If you must criticize her,” says Rubin, “do so in a way that empowers her.” She says her goal is to get the girls to the point where they can refurbish their own chips by knowing and valuing who they are, and by having the ability to shrug off people who put them down.

“But,” she qualifies, “the backbone must come from the home. Schools cannot compensate for dysfunctional homes. The home needs to provide the child with a large dose of emotional stability in order for the child to really make it. And schools cannot do it alone — it’s a partnership.”

* Some names have been changed to protect privacy

No More Falling Through the Cracks

About five years ago, Montreal’s Bnos Jerusalem Girls School underwent some extraordinary challenges. The girls at this Belz elementary school were not going off the derech; still, many of them were very unhappy. They were feeling resentful that they had to work so hard to pass the Quebec Ministry of Education’s requirements (in French), couldn’t connect to the relevance of what they were learning, and felt imposed upon by an outside body they didn’t respect. This resentment began filtering down to their limudei kodesh studies as well, and many girls were displaying signs of disconnection and apathy. The school was desperate. “We were ready to try anything,” says Devorah Asseraf, Bnos Jerusalem’s secular principal.

Today, all that has changed. The girls are happy and the teachers feel they’re on the same team. According to Yocheved Wieder, Bnos Jerusalem’s limudei kodesh principal, “The girls are more engaged, more connected with one another, and their anxiety levels have dropped significantly.”

How did this transformation come about? Bnos Jerusalem implemented a number of changes — significant among them was the adoption of a school-wide reform called Response to Intervention (RTI), a multi-tiered approach to early identification of students with learning and behavior needs, using differentiation and several other means as well. Differentiation means tailoring instruction to meet individual needs, and most schools today use some type of differentiation, but RTI goes further, testing against the norms every time a new skill is introduced. The idea is to weed out students who will need special education outside the classroom from those who require an added scoop of instruction or other in-class interventions. The objective is, wherever possible, to keep students from becoming “resource-room children.”

“RTI is simply a way of looking at instruction and determining how any child with or without learning issues is responding to high quality instruction, whether it’s Common Core in NY State or limudei kodesh, with the school determining its own objectives and measuring tools,” explains Sheldon Horowitz, director of learning resources & research, part of the National Center for Learning Disabilities, a key RTI advocacy group. “It’s a systematic, evidence-based way of measuring progress, of intervening if children need something more to get to where they need to get. If you don’t find a way of measuring progress, then you are going to have children falling through the cracks. They may be passing from grade to grade, but then you’ll be scratching your head later wondering why they can’t read. The brightest students can mask poor decoding skills until it catches up with them.”

RTI basically changes the way teachers teach, according to Aviva Segal, Early Academic Intervention Consultant with Montreal’s Bronfman Jewish Education Centre (BJEC), the body that introduced RTI into Montreal’s chareidi and Hebrew day schools. Rather than seeing the student as the problem or leaving it up to the teacher’s gut feelings about a child’s ability (“I’m not worried, she’ll do fine”), students are tested and retested every time a new set of skills is introduced to see how well they’ve integrated those skills — instead of waiting for them to fail and then remediating. “If there are enough children in the class who are not picking up the lessons, perhaps it has to be taught differently. Is the instruction poor? Should the curriculum be adjusted, or perhaps certain children need to be taught differently or given more instruction?”

For Bnos Jerusalem, acquiring literacy skills is exceptionally challenging given that its girls must master four languages: English, French, Yiddish, and lashon kodesh. Based on literacy results, students are grouped by color, which indicates if, and how much, additional intervention they’ll need outside the classroom. Those hitting benchmark are designated green, whereas those falling slightly below are designated yellow. Reds are the most difficult cases, yet according to Dr. Carly Rosenzweig, BJEC’s Special Education consultant, “Yellows often fall through the cracks a lot quicker than reds, whose issues are more obvious.” She would like to see another designation added on as well. “These are the ones who are so far above the curriculum that they become behavioral problems later on because they’re bored.”

“Before RTI, there were those students who were managing and those who were failing,” says Bnos Jerusalem’s Asseraf. “And in between were the at-risk children who weren’t getting enough support because the system wasn’t set up to address them. They are the ones who fell under the radar. Now these are the ones the teachers will be talking to, getting to know, and monitoring their progress.”

Because the girls feel their learning issues are being taken more seriously and teachers have begun to adjust their instruction to meet individual needs, motivation on the part of the students has increased, as they now approach their teachers with struggles they may have ignored or sublimated before. Teachers say that the students are less anxious when reading out loud, and if they didn’t get it right, they are willing to try again using a different approach. “That’s huge,” says Mrs. Assaraf. “Once they see they can actually overcome their difficulties, they are better equipped to handle whatever challenges life brings.”

Just Ask Her

One way of reaching out to a girl before she becomes overwhelmed with seemingly insurmountable challenges is by getting to know her in a meaningful way, says Rochel Zimmerman, director of Torah Umesorah’s National Conference of Yeshivah Principals Women’s Division. “What are her interests and talents outside of school? How does she prefer to study? What excites her? Is she artistic? Musical? Children are excited to volunteer this kind of information, and it’s amazing what a teacher can discover simply by asking the child or her parents.”

Doing so empowers both students and teachers. It not only validates students’ differences, but astute teachers can use that information to structure the class in more meaningful and effective ways. Teachers might then group students according to interests or proclivities: the analytical girls, the artistic ones, those who are more research oriented or those who are more scientifically or mathematically inclined. By acknowledging their individual perspectives and differences, children become more engaged in their studies because they are being taught in a language that speaks to them personally.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 626)

Oops! We could not locate your form.