Battles and Baubles

Materialism pits us against anyone in our midst. It forces us to always compare what we have to what others have

“Hellenism and Judaism: when examined in depth, they are found to be the two leading forces that are again today struggling for mastery in the Jewish world.”

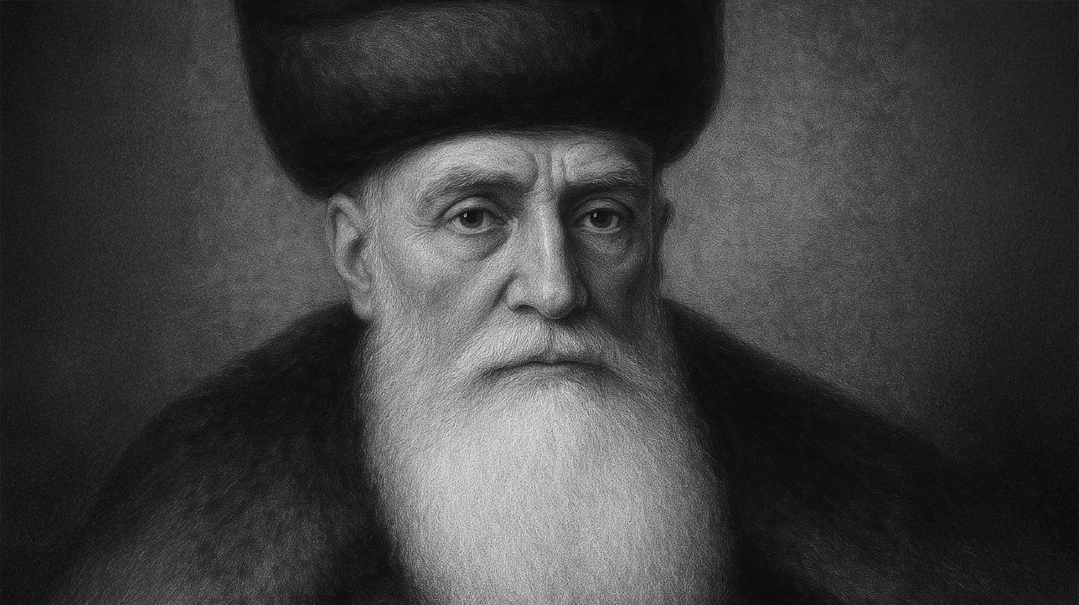

While these words were written by Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch in the mid-19th century in his Collected Writings Volume II, we know all too well how true they ring today. Hellenism, a worldview rooted in Greece whose emphasis on beauty has influenced the world, clashes with Judaism, both as a doctrine and a civilization. Both compete for mastery of the world and of our mind and spirit.

Yet in Judaism, we do not believe in the wholesale rejection of beauty. We use it to enhance our mitzvos, utilizing material possessions to complement our service of Hashem. So why does finding the right balance in today’s consumerist society sometimes feel like a battle of Hasmonean proportions? Why do we feel like we’re losing the war to stuff and baubles, despite our understanding that material goods are but means to an end and not ends in and of themselves? And why are we attributing so much importance to it all, as evidenced by our investment of time, energy, and resources?

It is crucial here to note the distinction between aesthetics and materialism. The dictionary defines aesthetics as a set of principles concerned with the nature and appreciation of beauty, especially in art. Materialism, on the other hand, is a way of thinking that gives too much importance to possessions and money and not enough to spiritual or intellectual matters.

One can be a person who appreciates aesthetics but is not materialistic. This means that one can be raised in a home that appreciates the finer things in life — good music, art, architecture, design — yet the focus is on the appreciating, not on the possessing. Money is not a prerequisite to valuing aesthetics. We do not have to buy the Monet we are taking in at the art museum to appreciate it. But we can take that aesthetic we have acquired from our exposure to beautiful things and utilize it in our own lives within the restraints of our budget, values, and religious beliefs.

The Torah approach to aesthetics can best be encapsulated in the brachah Noach gives to his descendants: “Hashem gave beauty to Yafes and he shall dwell in the tents of Shem” (Bereishis 9:27). Beauty is manifested in its ultimate form when it lives in the tents of Shem, when it is restrained within the confines of spirituality. Noach’s brachah acknowledges that Yafes’s gift is important and valuable, but only if it serves a greater truth, as represented by Shem.

As Rav Hirsch explains, “Without an external ideal that controls and directs both the perceptions and expressions of beauty, man descends to immoral and unethical hedonism. This is the beauty of Yafes divorced from the tents of Shem. Together they are the perfection Noach envisioned. Separate, they are the tragedy that fills the history of the world.”

The field of social science confirms that materialism can result in the tragedies of both social destruction and self-destruction. As Rav Hirsch similarly reflects: “As long as Hellenism is not coupled with the spirit of Shem, as long as it prides itself on being the sole road to happiness, it falls prey to error and illusion, degeneration and decay.”

Social scientists define materialism as a value system that is preoccupied with possessions and the social image they project. So the materialistic person does not even need to value the aesthetics of the possessions he acquires; he most values the social image obtained from those possessions.

According to Tim Kasser, PhD, the author of The High Price of Materialism and Psychology and Consumer Culture, to be materialistic means to have values that put a high priority not only on having money and many possessions, but also on image and popularity, which are predominantly expressed via money and possessions. He explains that there are two sets of factors that lead people to have materialistic values: first, exposure to messages suggesting that materialistic pursuits are important, via friends, family, society, and/or media; and second, a feeling of insecurity or threat, such as social rejection or economic fear.

Materialism pits us against anyone in our midst. It forces us to always compare what we have to what others have. It is a never-ending competition of the have-nots — and haves — against the have-mores that leaves us always wanting the next best thing.

Regarding self-destruction, studies show that materialism is associated with anxiety, depression, and broken relationships. When the attainment of possessions is used as an indicator of success, and when happiness is defined by acquiring those possessions, our well-being suffers. Our self-esteem is tied up with the pursuit of material things, because we erroneously believe that having more money and things enhances our well-being.

Research via longitudinal studies has shown that as people become more materialistic, their well-being, as defined by good relationships, autonomy, and sense of purpose, diminishes. They experience more unpleasant emotions, depression and anxiety, and even physical ailments. They have lower levels of life satisfaction. As they become less materialistic, however, overall well-being increases.

So we like nice things, we want comfortable lives, and we may even be aesthetically inclined, but we’re all pretty clear that we don’t want to be materialistic. We know it’s not good for us, our children, or our bank account, and we’re very clear that the pursuit of gashmiyus is most certainly not a Torah value.

But let us revisit the tents of Shem. We may observe that sometimes our appreciation for aesthetics has in fact taken us out of the tent of our ancestor.

We know the lines between aesthetics and materialism have been blurred when our appearance and the way we spend our money to reflect our style are used to separate ourselves from others. When they are used to create social divides and class structures within our community based on socioeconomic status. When we’re more concerned with who has what than who people are. When we conflate aesthetics and beautiful things with money and power.

We know we’ve got it wrong when our appreciation for beautiful clothes, home decor, or cuisine leads to unhealthy behaviors, both psychologically and economically. When we feel like we are excessively focused on shopping, acquiring things, and being au courant in every material aspect of our lives. When we live beyond our means. And when we feel a pressure to not just have more, but look like we have it all.

We know we haven’t struck the right balance when we attribute too much significance to “types” and appearances and too little to people’s accomplishments, endeavors, principles, intellectual and spiritual strivings, middos, and inner value.

Finally, we lose sight when it’s more hiddur than mitzvah, when the beauty feeds our ego more than our neshamah, and when it no longer becomes a means to an end because we’ve spent so much time, money, and emotional investment on the means. Beauty can so easily turn garish and pretentious.

In the secular world, we are bombarded with appeals to buy more because our society functions as long as people continue to spend. We continue to need more and want more of everything that is flaunted in our face. Sometimes it feels that frum society is challenged by the same consumerist ethos. It takes tremendous willpower and loyalty to our deepest values to just say no. I don’t need it. I have enough. I am enough.

So we are engaged in a battle that began with Mattisyahu, and there seems to be no letting up. Perhaps we should return to the timeless messages of Chanukah to receive our marching orders. We can remember the symbolism of the Menorah, whose opulent external appearance was always a means to an end, a vessel of the finest materials and aesthetic design used to embellish the candles, which represent the Torah and mitzvos.

Rav Hirsch suggests kindling the menorah as the very antidote. The menorah proclaims to us and the world where our true loyalties lie, even if we are tempted, swayed, and influenced by the glittering objects around us:

Thus if a glimmer of the false Hellenistic spirit challenges the dominion of the timeless spirit of the Jewish Law over the dwelling and hearts of Judah; if it estranges Judah’s daughters and sons from the splendor of G-d’s Law and His Divine light and makes them fall prey to the beguiling sensuality of Greek culture; if they are made to abandon truth and insight, harmony and beauty and to adopt the empty superficiality and sensual gratification of Hellenism — then let us kindle the light of the Hasmoneans in our homes as a tribute to G-d and His Law. Each Jewish home will become a bastion of G-d’s Law and rise triumphantly and victoriously over the futile opposition and antagonism of an erring world.

May Hashem illuminate our path forward and give us strength to live up to our long-held values and ideals, bayamim hahem bizman hazeh.

Alexandra Fleksher is an educator, a published writer on Jewish contemporary issues, and an active member of her Jewish community in Cleveland, Ohio.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 941)

Oops! We could not locate your form.