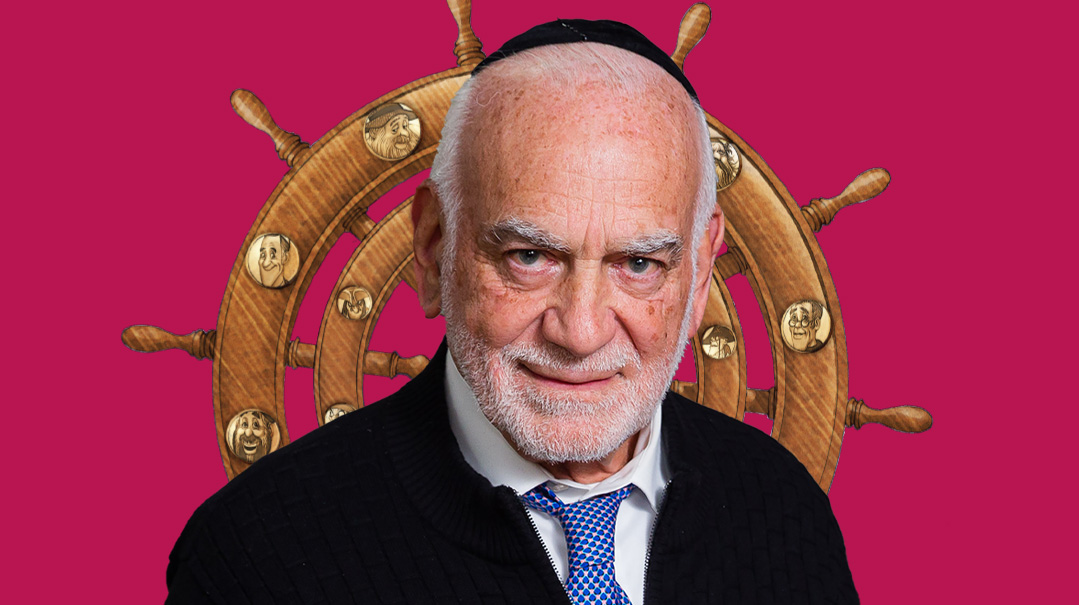

Back at the Wheel

Rabbi Baruch Chait and Gadi Pollack return with another middos masterpiece

Photos: Elchanan Kotler

Illustrations: Gadi Pollack

Nearly twenty years after master mechanech and veteran composer Rabbi Baruch Chait teamed up with beloved artist Gadi Pollack to create four best-selling books of the Middos Voyage series for children, they’re finally back with the next chapter in the lives of Rebbe Lev Tov and the passengers and crew on the Gaavatanic oceanliner. But while those children are now adults themselves, the duo’s newest message is actually targeted to them, too.

IT’Sbeen over two decades since children were first entranced by The Incredible Voyage to Good Middos: the story of the unsinkable Gaavatanic, its love-to-hate-them passengers, and the earnest Rebbe Lev Tov, determined to bring the gigantic boat of haughtiness and greed to humility and repentance.

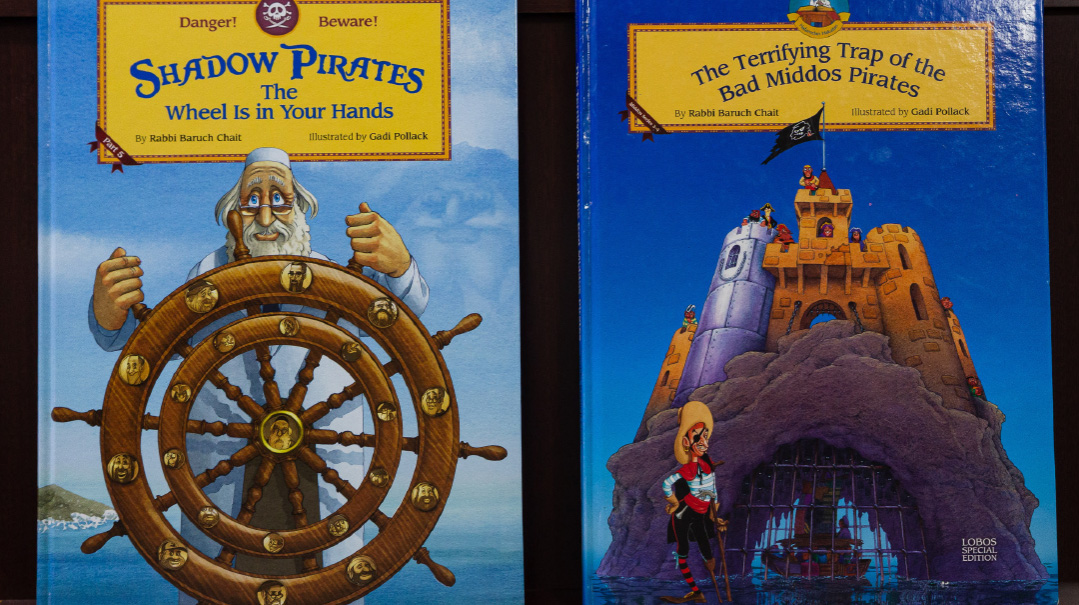

Books two, three, and four of the loveable Middos Voyage series quickly followed — The Lost Treasure of Tikun HaMiddos Island and parts one and two of The Terrifying Trap of the Bad Middos Pirates. And then the children of the world waited for book five. And waited.

In the world of frum Jewish children’s literature, these books were groundbreaking. Not only did they feature Gadi Pollack’s trademark illustrations with captivating depth, they also conveyed the child-friendly messages of avodas hamiddos created by veteran composer, writer, mechanech, and yeshivah founder Rabbi Baruch Chait. Readers were enthralled by the Gaavatanic and its crew, and clamored for more.

And now, 20 years later, when those same children have grown and started families of their own, Rabbi Baruch Chait and artist Gadi Pollack are at long last giving us the next chapter in the lives of the passengers of the Gaavatanic: Shadow Pirates — The Wheel Is in Your Hands.

What brought the duo back to the drawing board, and how does this new offering complement the previous books in the series even as it reflects the changing trends and needs of a new generation?

“Those kids who were the original readers are all grown up now, so the images became more mature as well.” Rabbi Baruch Chait and Gadi Pollack regrouped for a new generation

Many Are the Thoughts

I knock on the door of the Chait home in Jerusalem; someone calls out to come in. I push the door open and step into a cultural experience. An aquarium of burbling fish, a canary in a cage, a piano, and several guitars are interspersed around the wall-to-wall shelves of seforim in the tasteful Har Nof apartment.

“Lashon hara!”

I jump and turned around to find myself face to face with an extremely large, African grey parrot. He cocks his head and clicks his nails on the bars of the cage.

“Lashon hara!” he cautions me again.

I’m about to protest that I haven’t even said anything yet when Rabbi Chait comes bustling in from the other room.

“Careful, Cocoa bites,” he warns. I step back hurriedly, and we sit down at the table.

“He can also whistle the first stanza of ‘Mi Ha’ish,’ ” Rabbi Chait says, referring to the iconic song he composed back in the 1960s and made famous by his singing ensemble, The Rabbis’ Sons, the group that brought a new vibe to modern chassidic music with catchy, guitar-driven songs layered with depth and meaning.

Rabbi Chait sits by the piano and plays for a moment; it’s elevating.

“Do you still compose?” I ask, taking in how natural Rabbi Chait seems at the piano.

He smiles. “Every Thursday we have a kumzitz at Maarava Machon Rubin [the high-level yeshivah high school he founded in Moshav Mattityahu 35 years ago, which offers matriculation studies alongside limudei kodesh]. Boys make siyumim, we have a mussar seder, and then we turn down the lights. I take out my guitar, and those talmidim with guitars accompany me. At least once a month I try to teach them a new niggun, something I’ve composed. Last week, popular radio host Menachem Toker came down and recorded us, and then played some of our niggunim on his Motzaei Shabbos program on Radio Kol Chai.”

A big part of the chinuch in Maarava, Rabbi Chait explains, is understanding that sometimes it’s necessary to take a break for a pure activity — like music — in order to rejuvenate oneself to continue learning Torah. “My father taught me that,” he says, referring to Rabbi Moshe Chait ztz”l, the venerated rosh yeshivah of Chofetz Chaim in Jerusalem.

I’d grown up listening to oldies like The Rabbis’ Sons and Diaspora, alongside the more contemporary Avraham Fried and Yaakov Shwekey, and I have a deep-rooted appreciation for the folksy, chassidic-tinged music. For me, this was a trip back to the roots of the sounds that were the backdrop of my childhood.

“How did you start composing?”

Rabbi Chait turns around on the piano bench. “I was very involved in summer camps — Torah Vodaath, Camp Munk. And then I was head counselor in Sdei Chemed. It led to very unusual chinuch opportunities, where I could encourage the boys to express themselves outside the usual structures of learning. It really brought out the neshamah of a lot of kids. We had Pirchei singing groups, concerts in Eretz Yisrael, and it broke open new venues for music.”

He stands up and lifts a beautiful navy-blue guitar. “My main inspiration for my music back in the 1960s was Shlomo Carlebach. In fact, Abie Rotenberg and I even created an album with him later, in 1975, called Ani Maamin. Abie was in charge of the children’s choir, and I headed the overall production.”

“Rabos Machshavos” was Rabbi Chait’s first well-known composition, featured with “Mi Ha’ish” and several other classics on The Rabbis’ Sons’ first album, Hallelu, in 1967. (After their fourth album, the group broke up, with Rabbi Label Sharfman creating Dveykus and later a seminary, and Rabbi Chait creating Kol Salonika and later a yeshivah.) What made people take notice of The Rabbis’ Sons wasn’t only the fresh niggunim, but the arrangements — the ’60s-style of using only guitars with no other instruments gave the songs a contemporary country sound, which was pretty cutting-edge at the time for Jewish music. While some critics thought it wasn’t “Jewish” enough, others realized it was just what their kids needed.

“My friends from Yeshiva Chofetz Chaim and I actually decided on a record when it was my turn in the rotation of students to raise money for the yeshivah,” Rabbi Chait recalls. “I asked our rosh yeshivah, Rav Henoch Leibowitz ztz”l, if we could make a record in order to bring in money. At first, he agreed, but when he heard the music, he said he’d prefer if it didn’t have the yeshivah’s name on it. It was too new, too revolutionary, as we used only guitars and harmonies — which became the classic kumzitz sound.

“You know,” he continues as he strums, “a niggun has three parts to it, much like a person: The lyrics are like the head, the melody is the neshamah, and the arrangement is the clothing. In hindsight, I can see that our arrangements were too new and different for the time. Later I sat with Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach ztz”l, and he explained to me that all music is permissible as long as it’s devoid of pritzus and avodah zarah. And today we know so much more about the kochos of beautiful music. Dovid Hamelech would use different instruments, alei asor va’alei navel, alei higayon b’chinor, and he said each one would provide him with a different kind of connection to Hashem.”

One Page at a Time

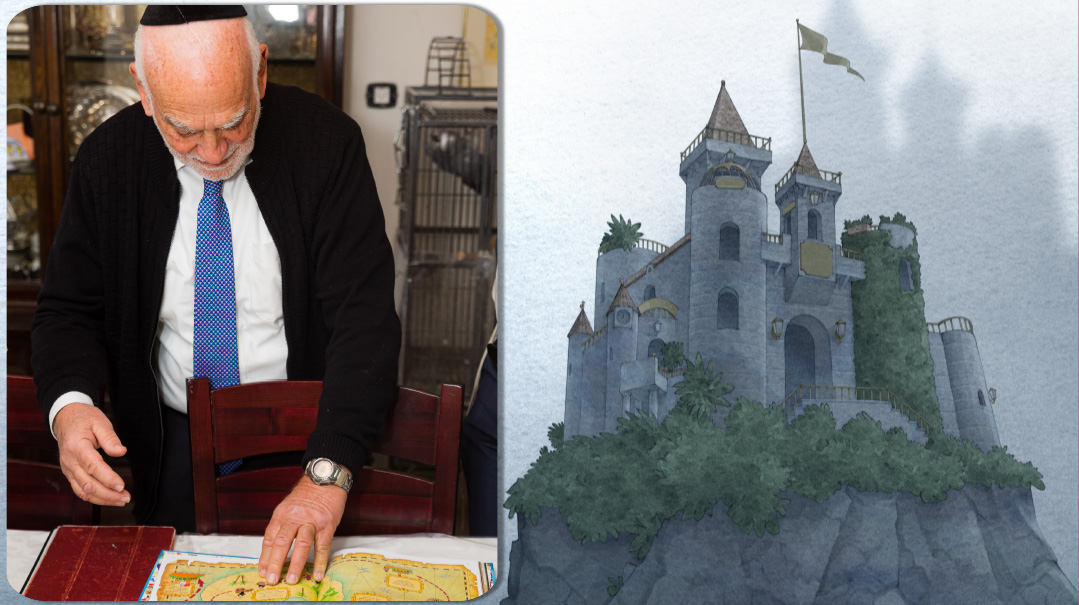

Back at the dining room table, there’s a scattered treasury of Rabbi Chait’s projects: The 39 Avoth Melacha of Shabbath book that was the staple of every Jewish home growing up, the vivid and haunting Katz Haggadah shel Pesach, and the rest of the Pirate series. I can’t resist opening the new book, Shadow Pirates, and turn the glossy pages slowly.

“It’s darker than the other ones,” I comment.

“Lashon hara!” Cocoa squawks.

I look around doubtfully. I hadn’t meant it negatively. “I’m just curious why,” I explain (to the parrot?).

Rabbi Chait obliges. “Well, I wrote this book for the children who were clamoring for another volume, but those kids are all grown up now, so the colors became more mature as well.”

I flip through more pages, admiring the incredible illustrations. “So you and Gadi Pollack just picked up where you left off? How did the partnership first develop?”

He passes me The 39 Avoth Melacha of Shabbath book. I remember sitting on the floor of my childhood shul, flipping through a worn-out copy with the binding peeled off.

“For my first project, I was set on using artist Yoni Gerstein whose work I’d discovered, and so I searched long and hard until I tracked him down. But later, when I was ready for the Middos Journey books, he wasn’t available, so he introduced me to his talented colleague, Gadi Pollack, who had recently broken into the market and had asked Yoni to send customers his way.”

I ask him to describe the artistic process for two such huge talents, especially considering that Gadi Pollack himself has emerged as a book author as well as an illustrator.

“Well, if you want to hear how not to create a book, I’ll tell you,” Rabbi Chait says.

While most authors create a story board for illustrated books — an outline of how many pages there’ll be, how many words per page, and how many illustrations will be needed — Rabbi Chait, busy with his yeshivah, works on one spread at a time.

“First of all, we’re good friends, we believe in each other’s work, and have tremendous respect for each other. I send Gadi a page, he sends something back to me, I tell him it’s not what I was imagining, at two a.m. we discuss some changes, he sends it back perfect, and we continue to the next page.”

Before the first book emerged, Rabbi Chait approached Gadi Pollack and explained that he wanted to create a book about middos, something based on Orchos Tzaddikim. “Okay,” Gadi said. “How should we do it?”

“We’ll see,” Rabbi Chait answered. “Let’s think about it. First of all, read Orchos Tzaddikim.”

Gadi read it. “Okay,” he asked Rabbi Chait, “now what?”

“For the first book, The Incredible Voyage to Good Middos, my original idea was to use the Dor Haflagah from Sefer Bereishis,” Rabbi Chait reflects. “I told this to Gadi, and he started sketching and creating folios. We were talking about a ‘tower of gaavah.’ And then one night I woke up with a jolt and called Gadi. ‘No, no more tower. We’re using a Titanic-spinoff. The Titanic was the ultimate in gaavah.’ And so, Gadi studied images of the Titanic until he knew the ship down to its last plank.”

Why the change from the Dor Haflagah? I ask. I can picture an illustrated book of comically-terrible characters gearing up to fight the Heavens. But Rabbi Chait has a simple explanation. “Because we’re all on a journey. And the Gaavatanic reflected that.”

I look down at the new book. “So this is the next chapter in the journey? Why now?”

“I guess you could say it was time,” he says. “And my wife Paula was tired of people stopping her in the grocery to ask for a continuation. She’s a therapist with a private practice, she deals with some very difficult issues in the community. And she urged me to carry on now — she said it was necessary.”

Rabbi Chait opens a copy of the book as well. “We left the weary travelers and the pirates-turned-good in the Good Middos Palace in the last book, back in 2003. Now, the message I came back to convey is that no one can reside in a Good Middos Palace, untouched and untested. People tend to believe that avodas hamiddos is a done job. That ‘I conquered this, I conquered that, on to the next one,’ etc. But that’s far from the truth. It says in the Chovos Halevavos that someone who develops a control of a middah is especially susceptible to a yeridah in that particular middah. We can’t just stay in the castle — we need to be constantly aware, constantly vigilant to work on ourselves. And that’s what Shadow Pirates is about.”

Rabbi Chait points to the cover, where the endearing Rebbe Lev Tov (who some people think bears a resemblance to Rabbi Chait) has two hands on a large ship steering wheel.

“See that over his shoulder?”

I squint into the blue mist and blink: A faint sneering face is evident amid the smog. “Who’s that?”

Rabbi Chait smiles. “That’s his shadow.”

“Lashon hara!”

No Light without Dark

Today, Gadi Pollack, who lives with his family in Kiryat Sefer, is a name unto himself, having evolved into a writer and book producer as well as an illustrator, with his best-selling, multi-language Once Upon a Tale series featuring Fishel, Berel and Shmerel, Robert, Reb Zalman and other beloved characters, PurimShpiel, A Tale of Seven Sheep, the A Yiddishe Kop series, and more.

The best time to catch him is after 11:30 p.m., after his night seder.

“Were you surprised when Rabbi Chait reached out about this project after a 20-year hiatus?” I ask.

“Well, I wasn’t in the country when part two of The Terrifying Trap of the Bad Middos Pirates, which was our last installment, came out. When I got back to Kiryat Sefer and opened my copy, I was really surprised to find an ad on the last page advertising a continuation. It was news to me — we hadn’t even talked about it. So I called up Reb Baruch, and he said the graphic artists had an extra page in the back of the book, so he told them he needed to think for a moment. And then he came up with an idea for a new book — even though it took 20 years. But you’d be surprised how many people have asked me about the next book over the years.”

He admits, though, that the initial feedback from the groundbreaking concept was ambivalent. “Some people really didn’t know what to make of it, and there was some harsh criticism as well. But do you know my method for never receiving criticism? It’s never, ever to actually do anything.”

I complimented him on the illustrations, the depth and sense of motion that are so apparent on each page, but he shrugs it off.

“That’s all technical, and pretty simple,” the Russian-born artist says. “The hard part is getting Reb Baruch’s message across through a picture.”

Over the last 20 years, as Gadi Pollack’s own books have become bestsellers, working as an illustrator for someone else is a challenge he hasn’t done in a while.

“First of all, I’ll never do a project I don’t believe in. And anyway, today I no longer take on projects — I have too much of my own work. But I can’t say no to Reb Baruch — he’s an attractzia, he’s a change of pace.”

“And are you happy with how the newest book came out?” I ask, getting the sense that he and Rabbi Chait get a kick out of each other.

“When I work with Reb Baruch,” Gadi says, “he tells me his idea, I give my input, and then we hash it out — but at the end of the day, it’s his brainchild. So it’s different than when I work on my own projects.Here, I follow his lead. I just try to make sure the final deliverable piece is a quality one. And if I didn’t believe in it, it would never work in the first place.”

Gadi Pollack was born in Odessa, Russia, into a family of musicians, and that was the path naturally charted out for him as well. But although he studied piano for four years, his real love was drawing, and begged his father to send him to art school.

At 15, Gadi went to Academia, the equivalent of university, to study art. He initially became a sculptor, an art form he studied for four years, and was then conscripted for two years of mandatory service in the Russian army. (He didn’t see combat, though — he was stationed in the army newspaper department as a graphic artist.)

After his military service, Gadi worked as an artist for an advertising firm. His Jewish identity was reawakened after a priest asked him to create a comic strip with Bible stories, an offer that led him to study Tanach, move to Eretz Yisrael, and begin learning full-time in yeshivah. Living in Kiryat Sefer today, he still tries to get in two sedorim of learning.

“Do you ever wish you could do whatever you want, without the confines of a specific readership?” I ask him.

The artist’s tone turned wistful. “If I did whatever I wanted, I would have left art and followed in the footsteps of my friends who are today talmidei chachamim and roshei kollel.”

I wasn’t expecting that. There’s silence, and then I mention how I found the pictures darker in this new book.

He seems pleased with the observation. “You know, you can’t portray light in an illustration unless you also have shadows.”

The wheel’s in your hands. Will it be the outer good personas, or the inner alter ego?

Contours in the Shade

And shadows are really an underlying theme here. “We all have shadow selves, parts of us that reflect the worst in us,” Rabbi Chait explains. “And for this book, I put the shadows in charge. The characters mimic their shadows instead of the opposite. The shadows gain control, fed by the bad middos left untouched and unworked on inside these pirates-turned good. Because you can’t just sit and be complacent.”

He points to the cover of the book again. The outer wheel of the steering wheel has all the pirates’ good personas etched into it. The inner wheel, though, has the pirates’ bad alter egos etched into it. “That’s what it means that the wheel is in your hands,” the educator of over 60 years says. “Gadi first sent me the sketch of the cover with a smile on Rebbe Lev Tov’s face. I told him we need to change it to something more serious.”

I look at Rebbe Lev Tov’s new, neutral expression. “He doesn’t look upset,” I say.

Rabbi Chait nods. “Right, he’s not upset. Ivdu es Hashem b’simchah. But he’s aware of his shadow self, hovering by his shoulder, waiting to pounce in a moment of weakness. So he’s vigilant of the choices in his hands. And that’s a sobering thought.”

“And that’s the message you wanted to give today’s generation?” I ask.

Rabbi Chait nods.

“And do you have hope for today’s dor?”

He looks up from the book. “I think our job as mechanchim is to have hope. I’ve been involved in education for over six decades. Yeshiva Chofetz Chaim instilled that in us, the ratzon to be marbitz Torah. I taught in Riverdale for two years, then my wife and I came to Eretz Yisrael with three small children and absolutely no income, in order to assist my father in Chofetz Chaim here. Four years later, we started Maarava in temporary caravans.”

“So as a mechanech, it sounds like the message here is a hopeful one.”

“It is,” he says, “because it’s packaged as a user manual, a how-to of sorts. We’re saying don’t make outward changes — like the Good Middos Palace that got a glittery paint job — without first fixing what’s inside. It’s a problem today, people work so hard to accumulate knowledge, to achieve great accomplishments in Torah learning, but they neglect to do the real work, the avodas hamiddos. And that means that they are allowing their shadows to take control. We have it all in here—” he taps the book “— the Orchos Tzaddikim and Pirkei Avos and Tehillim, all the sources for true inner work.”

“So the light needs to come from within to conquer influences outside.”

“Exactly.”

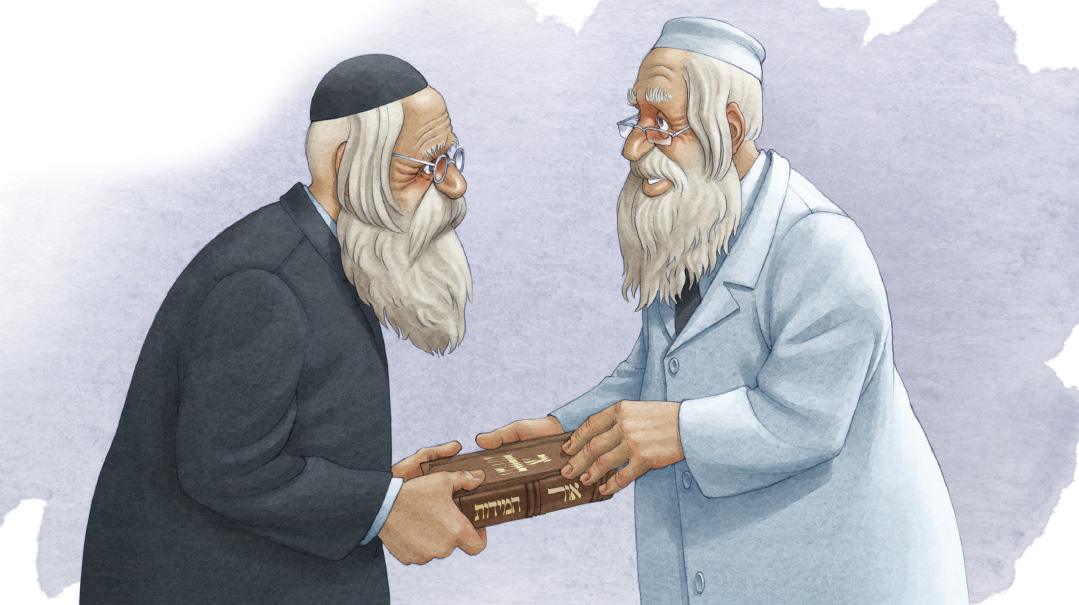

He flips to the back, to where (spoiler alert) Rebbe’s rebbe has opened up a sefer titled Ohr Hamiddos and is shining a light toward the men. “If you shine a light directly at something, the shadows disappear,” Rabbi Chait explains.

“What is sefer Ohr Hamiddos?” I ask.

“It doesn’t exist yet,” he says. “That’s my next project.”

Be Someone

Rebbe Lev Tov was always the voice of good, the angel on the shoulder, so to speak, throughout the travelers’ lengthy journey. Yet in the Shadow Pirates: The Wheel Is in Your Hands, he loses himself when giving mussar to the men, and his rebbe needs to step in and remind him of his own lurking shadows.

Because, Rabbi Chait explained, he wanted even the ones who seemed above reproach to remember that they too can fall.

“Al taamin batzmecha, don’t believe in yourself until the day you die, but also al taamin, don’t develop tendencies, don’t turn complacent.”

“Today,” I chime in, “people are very big on acceptance, accepting who they are, their limitations. How does this fit into that warning?”

Rabbi Chait, ever the educator, explains how the Vilna Gaon expounds on the words, “Eizehu ashir, ha’sameach b’chelko”:

“This holds true not just monetarily, but also in spiritual accomplishments. If you’re always criticizing yourself, you can’t serve Hashem b’simchah. In Slabodka, in Novardok, they had vigorous mussar sedorim. Today, people aren’t capable of that. But it’s necessary, it’s so necessary.

“So here, we packaged it humorously, with Gadi’s incredible illustrations and a fun storyline, but we want to shake up awareness. And you know, I once asked Rav Shmuel Kamenetsky what the most important message to impart to children is, and he said, ‘Simchas hachayim.’ But when I asked him what seforim will teach them this, he didn’t have a definitive answer. I once read in Alei Shur about working on ‘sense of humor’ during the Aseres Yemei Teshuvah. Which makes sense: learning how to let things slide, and how not to take oneself too seriously, are all integral aspects of avodas Hashem, not to mention that being mochel others’ slights is a good idea before approaching a reckoning with Hashem.”

I flip the book over and read the words on the back: “Torah chinuch is not simply developing a person to know something but rather to be someone. It’s not only what you know but who you are.”

“Who you are,” I say aloud. “Do you mean a yarei Shamayim, a baal middos?”

Rabbi Chait nods. “Yes. But also who you are individually, what your struggles are, what your particular journey will be.” He flips to the last page, a treasure map with small quotes sprinkled around. “You cannot control what will appear around the bend,” he reads, “but you can control your response to it.”

He looks up. “There’s no need to fall apart or to fall into despair. Be someone, be a worked-on, worked-out version of yourself. That is my message today to the grown-up children reading this, and to the youth as well. It’s a miracle we accomplished this after 20 years. It was a matter of great siyata d’Shmaya, and an honest collaboration between two partners. It says, ‘Chanoch l’naar al pi darko [Educate the child according to his way]…’ I have my own pshat on this: Chanoch l’naar — the youth that’s inside of you, keep fresh and well trained. Al pi darko — along its journey. Gam ki yazkin lo yassur mimenu — and then when one gets older, that youth within you will never leave.”

How apropos for the seemingly ageless, indefatigable man in front of me.

I stand up, tucking my copy of the new book into my bag.

“Don’t let the shadows in,” Rav Chait says as he bids me good night.

“Lashon hara,” Cocoa warns one last time. And with these messages, I step out into the Jerusalem night.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 942)

Oops! We could not locate your form.