Ancient as the Hills

Rabbi Ephraim Schwartz climbs the rough, rocky hills of Hebron

Photos: Eli Cobin

When the Meraglim came upon Chevron with its rocky, unhospitable terrain and population of giants, no wonder their hearts melted. But the strong of faith and spirit knew that in the zechus of the Avos, it would yet be an eternal inheritance. We’re still climbing

“Eretz Yisrael nikneis b’yissurim,”

Chazal tell us. Our country is only acquired with tribulations, with mesirus nefesh.

When I was a bochur in yeshivah, I thought it meant that you couldn’t get sour pickles or a decent pastrami sandwich here, and that they put chickpeas in the cholent. Today, baruch Hashem, we have it all, and yet for those of us privileged to live here with all the amenities Hashem has provided, there is still a desire to taste that mesirus nefesh of old, to connect to the sacrifices that are a necessary component of our precious yishuv. And the place I go to get that inspiration is the city of Chevron, the first city visited by the first Jewish tourists to Eretz Yisrael — the Twelve Spies we read about in parshas Shelach.

Where It All Began

I like to start a tour of Chevron from the place where our collective Jewish life started. We’re standing at the top of the hill called Tel Chevron, in the Jewish neighborhood of Admot Yishai (Tel Rumeida), where we have an incredible overlook of this area. On all sides of us we see Arab houses — the Arab population here is about 250,000, while the Jewish population is about 800.

If you think those odds are bad, you can imagine how Avraham Avinu must have felt when he lived on this very hill surrounded by his Canaani and Chitti idolater neighbors. This is where he had his tent open on all four sides for the wayfarers that he would be mekarev with food and drink and making a brachah. It’s here that the malachim came to give Sarah the news about Yitzchak’s birth and it could be in the next field that Yishmael did some target arrow practice on the apple on little Yitzchak’s head. (In fact, the ancient Spring of Avraham is nearby — a natural water source thought to date back to the times of Avraham and Sarah.) And it’s from here that Avraham embarked on the three-day journey to Har Hamoriah with his son Yitzchak for the original act of mesirus nefesh — the Akeidah. And so, it’s from this city that mesirus nefesh is first engrained in our national DNA.

As we look around we can’t help but notice how rocky these hills are. Chazal tell us that there is no place rockier than Chevron, which is why it was a central burial place for Klal Yisrael, as the hills are not conducive to planting or growing crops. Yet we notice that there are crops growing here in abundance, particularly from the Shivas Haminim of Eretz Yisrael. As we stand under one of the many abounding olive trees, we see the grape vines that the Tribe of Yehudah was so blessed with.

As we look down below to try to spot the Mearas Hamachpeilah, I open up my Chumash to find where I should be looking. The Torah tells us that after Sarah’s passing, Avraham Avinu approached Efron and asks to purchase the “doubled cave” at the edge of his field. There really are no fields here as it is so hilly, but there is one large place down below in the valley that is flat that stands out from these hills. And right there on the edge of it as it slopes up is the towering edifice of Mearas Hamachpeilah. But back then, it was just a cave with another cave inside, and below that Avraham discovered the tombs of Adam and Chava. Later Avraham and Sarah were buried there, as were Yitzchak and Rivkah. And then we have a really big levayah — perhaps the greatest funeral in the history of the world.

In parshas Vayechi we learn that Yaakov Avinu dies in Mitzrayim, and the entire country, the most powerful nation in the world at that time, shuts down in mourning for 70 days. Then Yosef gets permission to bring his father’s embalmed body to Eretz Yisrael and the procession begins — a journey through the desert and up and across the Jordan river. The Canaanim see the entourage and join the procession as well. These hills were filled with multitudes, all coming to give the final kavod to Yaakov.

But then it all comes to a halt. There’s a hairy, redheaded hooligan blocking the entrance — it’s Uncle Eisav! The Shevatim do what we Jews are best at and begin negotiations. Chushim ben Dan, having the benefit of being deaf, doesn’t understand what’s going on — or perhaps he’s the only one who really does —grabs his sword and removes Eisav’s head in one fell swoop. So next time you come here to daven at the kever of our Avos, you might want to ponder that fact that Eisav’s holy head is here too.

First Throne

We walk around the hill to a group of caravans and a modern residential apartment building built right over the ancient ruins of this city. Archaeologists recently discovered jug handles and seals that are inscribed in ancient Hebrew script with the words “Lamelech” (“to the king”) and “Chevron.” Dovid Hamelech’s first capital in Eretz Yisrael was here for seven years before he centralized the kingdom in Jerusalem, and he most likely built his first palace on this strategic hilltop where the Avos lived.

In modern times, the entire area of the Tel was officially purchased by the Jewish community in the early 1800s (the document, in Arabic, states that the purchase is for posterity), but Jews only resettled the area in 1984, when the government gave the renewed Jewish community of Chevron permission to build a residential section and moved in the mobile homes that are still here.

Walled In

One of the most remarkable finds on the Tel is the remains of a huge wall, one of the widest and largest walls found in Eretz Yisrael, dating back to the time when Bnei Yisrael came into the land — and it’s even mentioned in the Torah. When the Meraglim were told to scout out the land, this was their first stop — and the first time the Jews had been back to Eretz Yisrael in over 200 years.

Calev ben Yefuneh brings them here so that he can daven by the Avos, but whereas Calev comes to daven, the spies see giants and huge walls and unconquerable cities. They see this wall. Do we have the mesirus nefesh to overcome the walls and the giants that Eretz Yisrael presents, or not? Calev knows we have zechus avos and Hashem’s blessing for success, and he and his progeny merited to inherit this city of fortitude. But the Meraglim sadly only see their human frailty and limitations, and it would be another 40 years and hundreds of thousands of our ancestors dying in the desert until the time would come for re-entry.

Across from Admot Yishai is an army base, and right behind it is the double kever of Rus and Yishai. We have a mesorah of this location that goes back to ancient travelers who would visit the spot (and the location was also confirmed by the Ari Hakadosh, who identified ancestral graves around the land when he came to Eretz Yisrael in the 1500s). Even though Yishai, Dovid’s father, and Rus, his great-grandmother, lived a distance away in Beit Lechem, Dovid Hamelech wanted them buried near his palace, and near the Avos, as a source of inspiration and prayer.

Yishai is one of the four people, Chazal tell us, who died without any aveiros; and Bubby Rus is the exemplifier of mesirus nefesh, having left behind her entire world and royal kingdom to do chesed with Naomi and join the Jewish People. Every year on Shavuos, her kever is packed with Jews from the local community and visitors who come for Yom Tov to bask in her energy.

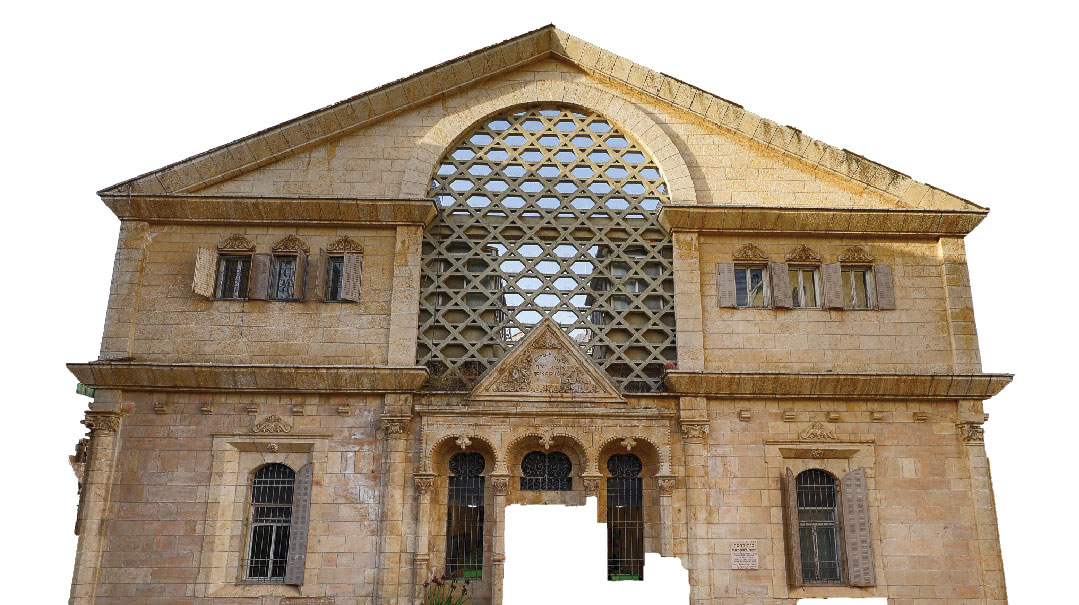

Hospital of Hope

As we head down the hill, we approach a big, beautiful, renovated building that has become the visitor center for Chevron. This building, the Beit Hadassah complex, was originally built in 1893 by Chacham Chaim Rachamim Yosef Franco (known by his acronym HaCharif), the leader of the Sephardi kehillah at the time. The building was originally called Chesed L’Avraham, and served as an infirmary for both Arabs and Jews. A few years later, the Hadassah women’s organization took responsibility for the medical staff.

During the bloody Shabbos massacre of 1929, in which Arab rioters murdered 67 Jews and injured hundreds more with axes and knives, the clinic — which had served as a model of coexistence — was looted and burned. And the Jews, who had been living in the city for centuries, were expelled.

With the liberation of Chevron in the miraculous victory of the 1967 Six Day War, excitement grew around the possibility of reclaiming and restoring Jewish property and renewing Jewish life in Chevron. The government wasn’t exactly on board, but the following Pesach, a group of likeminded families, led by Rabbi Moshe Levinger a”h, camped out in the Park Hotel, where they remained for several weeks until the government moved them to the IDF military compound — their home for the next three years during negotiations to build the adjoining town of Kiryat Arba.

But the dream of moving into Chevron proper was never extinguished, and one night in 1979, the timing was right. With Menachem Begin, Israel’s first right-wing and traditional prime minister in charge, the Kiryat Arba families who’d been biding their time felt their chance had finally arrived. Ten women with about 40 children, led by Rebbetzin Miriam Levinger and Sarah Nachshon, snuck into the boarded-up, abandoned Beit Hadassah building and barricaded themselves in, refusing to leave until Jews were permitted to return to Chevron. Begin was not someone who was going to expel Jewish women and children from their ancestral homes, yet the law was the law. So he allowed them to stay on the condition that no one else was allowed in and that anyone that left could not return.

For a year these women and children remained there alone. Food would be sent in through the windows, and the army eventually hooked up running water and electricity. Their husbands and other men would come each Friday night and make Kiddush and sing Eishes Chayil from the street below. But all that changed one Friday night in May 1980, when Arabs opened fire on a group of young people as they approached the gates of Beit Hadassah for Kiddush, killing six (including two American yeshivah bochurim) and wounding another 16. Only then, in response to the shocking attack, did the government agree to authorize an organized return of Jews to the Ir Ha’avos.

Trails Through Time

Today, the top floors of the renovated Beit Hadassah are a modern apartment complex housing several dozen families, while the bottom floor contains a captivating museum, with vintage pictures, interactive videos, and even a multimedia film with moving seats and all. It’s a fascinating place for learning about the history of near-continuous Jewish life in Chevron throughout the centuries.

During the period of the First Beis Hamikdash, Jews would travel along the ancient derech ha’Avos from here to Jerusalem to be oleh regel, but after the failed Bar Kochba revolt hundreds of years later, the emperor Hadrian set up slave markets here, selling the Jewish prisoners cheaper than a loaf of bread.

Throughout the generations, travelers and gedolim documented their visits to the city. Rav Binyamin of Tudela and Rav Ovadia m’Bartenura spent time here. The Rambam established the day he arrived in Chevron — one of Eretz Yisrael’s four holy cities — as a Yom Tov for all his descendants, and the Ramban even purchased a grave here. It was a city of mekubalim and scholars, and some of those who dwelt here include: the Reishis Chochmah, Rav Yisrael Najara, the poet of many of our Shabbos zemiros who lived here before moving to Tzfas; the Meleches Shlomo; the Sdei Chemed; and the Chesed L’Avraham, Rav Avraham Azulai and his grandson the Chida, to name just a few .

The story is told about the Chesed L’Avraham and the Turkish sultan, whose sword fell into the cave under the Mearas HaMachpeilah while he was peering into the underground channel. They lowered some soldiers into the cave to retrieve it, but one after another they came up dead. Finally, it was decided to send in a Jew, and Rav Avraham volunteered for the task. After fasting, he was lowered down into the cave. Upon reaching the bottom he saw three saintly men standing there with the sword. He understood that these were the Avos and he expressed his desire to stay there with them, as he was already very old. They told him that he must return, but he shouldn’t be disappointed, for in a week he would be with them once again. Rav Avraham went up and returned the sword, and sure enough, a week later he died in his bed and was buried in the city’s ancient cemetery.

After World War I, the Slabodka Yeshivah, under the leadership of Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein and the Alter of Slabodka, Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel, moved to Chevron. In Chevron, the yeshivah flourished, with over 200 students and avreichim. But it all came crashing to an end with the horrifying pogrom of 1929, where dozens of talmidim were killed and many others injured. Their stories of mesirus nefesh al kiddush Hashem are all recorded here in the Beit Hadassah museum and continue to inspire the daily visitors to this city.

Holy Woman

Today the Beit Hadassah neighborhood contains a string of renovated Jewish buildings, including next-door Beit Shneerson, Beit Romano (which houses Yeshivat Shavei Chevron) and others, each of them with their own special story and history.

In the mid-1700s, Rav Gershon Kitover, the brother-in-law of the Baal Shem Tov, arrived with the first community of chassidim to this predominantly Sephardic town. In the early 1800s, the fourth Lubavitcher Rebbe called on his followers to return to Chevron, and the community grew and was strengthened with the arrival in 1845 of Rav Yaakov Kuli Slonim and his wife, Rebbetzin Menuchah Rochel Slonim, daughter of Rebbe Dov Ber — the “Mitteler Rebbe” — and granddaughter of the Baal HaTanya (she was born the day he was released from prison).

For decades they led the chassidic community, and Jews and Arabs alike sought the blessings of the Rebbetzin, who was known as the matriarch of Chabad chassidus. Their home was called Beit Shneerson, and it was probably the first time Chevron had a real heimishe cholent kiddush. That cholent is still being served by Chabad today, whose nearby visitor’s center offers hospitality to guests and to the soldiers who patrol the city.

Rebbetzin Menuchah Rochel lived to be 90 years old, living through the leadership of the first five Lubavitcher Rebbes. She passed away on 24 Shevat, 1888, and is buried in Chevron’s ancient Jewish cemetery, where her grave has become a place of supplication and salvation.

Guest of Honor

As we walk down the main street connecting the Jewish enclaves, the next stop on our way to the Mearas Hamachpeilah is the Avraham Avinu shul in the center of the renovated Avraham Avinu neighborhood. The shul was built in the 1500s by Jews who had fled Spain, but in modern times it went through decades of desecration. After 1929, the Arabs turned it into a goat and sheep pen and a public bathroom for shoppers in the adjoining casbah. The neighborhood was reclaimed together with Beit Hadassah, and the Levingers were the first tenants.

The shul got its name in 1619 when a plague ravaged the city and most of the Jews left for safer Jerusalem. Yom Kippur arrived with only nine people for Kol Nidrei — that was until a mysterious old man with a long white beard came in to join them for the services. He remained throughout Yom Kippur, but when they looked for him to invite him for the meal after the fast… he was gone. They searched for him for three days, and on the third day he appeared to the chazzan in a vision: He wasn’t Eliyahu Hanavi though. Actually, he was Avraham Avinu, come to be mashlim the minyan for his children who were moser nefesh to remain in Chevron for the Yamim Noraim. To daven in the same shul where Avraham Avinu spent Yom Kippur is a perfect prelude to our destination, the cave where he rests, the entrance to Gan Eden.

Staircase to Heaven

As we walk into this massive complex, we note how the huge limestone bricks that make up this building are very similar to those of the Kosel. They were built with the same architectural design commissioned by King Herod, who built additions to the Beis Hamikdash complex as well as this structure. In the 1200s, Islamic conquerors added minarets and inscriptions in Arabic on all the internal walls, and for the next seven centuries under Arab and British rule, Jews and other non-Muslims were not allowed into this building. They could only go as far as the “Seventh Step.” The one exception was the Imrei Emes of Gur, who after a few well-placed “gifts,” was allowed up to the 11th step.

The Seventh Step, though, is actually the closest one can get to the actual cave, which is under this entire edifice. In an incredible story on the fourth day of the Six Day War, the day after Jerusalem was liberated, the IDF’s Rabbi Shlomo Goren (who would later become Israel’s chief rabbi) was told that Chevron was meant to be the next conquest for the army. He demanded to be there in order to be among the first to enter and daven, but the next morning upon awakening, he didn’t see his unit and assumed they had left without him. So he and his jeep driver drove to Chevron and climbed up these steps, shooting down the door as hundreds of Arabs came out waving white flags and surrendering to him personally. It was a few minutes later that he realized the troops were on the opposite hill, still waiting for him to arrive. They looked out with their binoculars and saw him signaling for them to join him. It seems that this gift was not meant to be given to an army. It wasn’t a military victory, but rather our Fathers reuniting with their sons.

We enter the inner area where the tomb markers are located, but the Arabic writing all over the walls is a stark reminder that the kivrei Avos are still not entirely in our hands. There is a decorative paroches with the embroidered words of Chazal about three places that were paid for in full, so that the nations will never be able to claim that we stole them: Har Habayis, the field of Shechem, and Mearas Hamachpeilah. How ironic it is that there are no places more contentious than these, where the world still makes that claim. (Some people might say that’s why you should never pay full price for anything.) But Chazal are not talking to the gentiles. They’re talking to us. So that we understand, for ourselves, that these places are, and will always be, unquestioningly ours, and that they be fully returned with the final geulah.

I open my siddur and close my eyes. All tefillos go up to Shamayim from the makom Hamikdash, but they come through here — the entrance to Gan Eden — first. Elokei Avraham, Elokei Yitzchak, Elokei Yaakov. Please, Hashem, remember Your people, for the sake of the Avos, and return all of Klal Yisrael to our home.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 815)

Oops! We could not locate your form.