All I Ask: Postscript

Soon after the first chapters were published, the questions and doubts came

A

It was early morning, the 11th of Tishrei, and the Succos issue of Mishpacha was waiting outside on my doorstep. Along with all the special Yom Tov supplements, the marketing department had added a CD to the package. Already after Tishah B’Av they’d begun dropping hints about the exclusive musical production that would be available only to Mishpacha subscribers and purchasers to enhance their Yom Tov.

A bochur, tefillin bag in hand, approached our house. He must have been on his way to Shacharis, that first pristine Shacharis after Yom Kippur. He bent down, delicately tore the plastic wrapper that held our Yom Tov Mishpacha, slipped the CD out, and hurried away with it.

We saw him from the window, but by the time we realized what had happened and went out to check whether our eyes had been deceiving us, there was no one to pursue.

The subscription department sent us a replacement for the stolen disk. So we had our music — but the incident left a deep, troubling imprint on me.

If, in the heart of a chareidi neighborhood, with the cries of Ne’ilah still echoing, a bochur in chassidic garb, carrying his tefillin, could enter a private yard and help himself to someone else’s property, then, then…

Then that meant he could murmur Kol Nidrei and five tefillos, and say Vidui ten times, fasting and shuckeling with his machzor open before him — and the next morning, go and steal.

And then go on to Shacharis, and shuckel some more, with his siddur open before him.

Maybe it was time to tell a story about people like that, I thought, about people who were withered, empty shells. Or about people who could end up like that, if nobody caught them in time. The people who stood with the rest of us, reciting the words in the machzor; who picked up the lulav with the rest of us and shook it right, left, up, down, and danced on Simchas Torah, and lit the Chanukah candles. The people who ticked off all the boxes.

What’s it like being one of them? I wondered. What goes on in such a person’s mind? What do they feel? What song sings in their heart (aside from the ones on our CD), and what cry of sorrow secretly steals out at night? They put on a good show, that’s for sure. Their friends and relatives don’t usually notice a thing. Only the wife at home watches with a fearful heart, and sometimes, even she doesn’t know…

The seed of All I Ask began to germinate, and I remain indebted to that bochur who made off with a CD and gave me a story.

Soon after the first chapters were published, the questions and doubts came.

“Are you sure you should be writing about this subject?” people asked me. “Why would you broach this topic in public? Aren’t you nervous?”

“Why should I be nervous?” I asked, aiming to clarify the question.

“Because you’re legitimizing it!”

In all truth I had some qualms, and I made every effort to write the story with sensitivity, consulting gedolim about my doubts. I discarded plenty of material, some of it very intriguing, because I felt a strong sense of responsibility to get my story right.

I don’t think the story gave anyone license to be apathetic about their Yiddishkeit. Anyone who was feeling disaffected was already feeling that way long before I wrote about it, and the story wasn’t advising anyone to feel that way or presenting it as some glorious, life-enhancing option. What the story was saying to these disaffected people was this: It hurts to be so disconnected, it’s painful to go through the motions when your heart and mind don’t work in sync — but there’s another option. You don’t need to suffer, and you don’t need to go off the derech, either.

I also got some feedback that I was offering some sort of “hechsher” to people who leave their native community or chassidus for a different one. I found the question strange. Read the story and you’ll know that I gave no approval to anyone. I told the story of a person who found an independent mashpia, and would probably have drifted away from Yiddishkeit if not for this mashpia. The story doesn’t take place in a vacuum; I have known several such people.

But if you truly know the history of chassidus, if you internalize the stories of tzaddikim who drew followers from all kinds of families and backgrounds, then you know of the parents and families who opposed the searchers’ quests, and of the seekers who kept searching anyway, because what they really sought was a vibrant bond with their Creator — even if that manifested in a different community, a different approach, a different derech.

Then there were the readers — many of them — who reprimanded me for “killing off” Lulu.

I don’t really know why they wanted so badly to see Lulu stay alive — so he should continue freezing in the Yerushalmi winters, sleeping in the streets, and go around shabby and unwashed, his beard growing wild? If they really cared for him, they’d be relieved that he didn’t make it out of the trenches alive. After all, Lulu is happy now. He’s in a good place, enjoying the Shechinah’s glow.

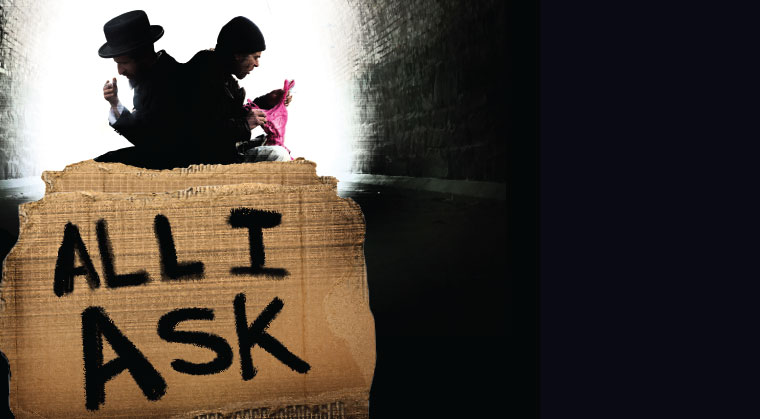

At the same time, I took the comments as a compliment. If readers are pained by the passing of this bothersome beggar who shakes his collection cup at them while they’re shopping for Shabbos and who sleeps on their sidewalks (and anyone who doubts the accuracy of these details can go out to Rechov Yafo any night and see how many “Lulus” are bedded down on the street — it’s heartrending), then apparently they got the message that a beggar is not some weird mutation, or wild anthropoid, or just an annoyance. He’s a person with a Divine soul just like us. He once had dreams, just like us, and maybe he still does.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 819)

Oops! We could not locate your form.

Comments (8)