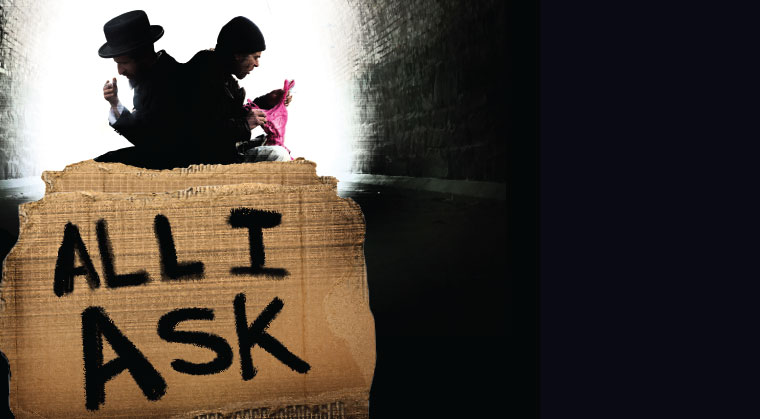

All I Ask: Chapter 8

Tzvika’s visit had its desired effect. Yanky got out of bed and went back to kollel. There was no sense in isolating himself in his room forever.

P

eople tried to be sensitive and nice, but he felt like a turtle without a shell, exposed and tender. Tatty was at home now, released on bail, and Yanky realized that the police had made an exception when they’d allowed him to visit his father. Suspects under arrest weren’t usually permitted to have visitors.

In the evening he dropped by his parents’ house, had some cake and tea, chatted with his mother and asked how Tatty was, mentioning not a word about investigations, arrests, or bail. It was almost as if nothing had happened.

At kollel the next day, the yungeleit all spoke admiringly of Reb Reuven Chaim, of his integrity. They were sure he was innocent of any wrongdoing. But something inside Yanky had cracked wide open, and he knew he’d never be the same again, not even if Tatty came out of this parshah squeaky-clean.

He couldn’t go on any longer just copying his father. It didn’t matter if Tatty was a tzaddik. Yanky had to find his authentic self — somewhere in there among the rubble.

At the edge of his mind, Tel Aviv’s Azrieli Towers kept rearing up in all their powerful sleekness. A triangular tower, a round tower, and a square tower against the sky. In the afternoon, he started making phone calls. Where and how could he become a licensed architect?

It would be a long process, he was told. First of all, he’d need to earn a high school equivalency diploma, and then, if he wanted a degree that would open doors to lucrative work, he would have to complete four years of study. All told, at least five years.

Five years! He would be 34 — practically middle-aged — by the time he was qualified.

“I know I’ll never really go ahead with it,” he told Raizele that evening. “I don’t have the courage to change my whole life. But I’m making the phone calls and looking into it anyway, just… just to allow myself to dream. Just to have that corner of my mind where I’m free to dream.”

Now his dream corner followed him wherever he went. He gazed at the details of buildings old and new. He gathered whatever knowledge he could of basic engineering, and he learned about the many branches of architecture. If he really could become an architect, what area of specialty would he choose? Would he be a technical architect, or would he go for a broader perspective and choose landscape design, or even city planning? What about conservation architecture? Preserving some beautiful old buildings could be rewarding…

(Excerpted from Mishpacha, Issue 764)

Oops! We could not locate your form.