All I Ask: Chapter 63

Tell him. Right now. Say the words Dad asked you to say. Just say it! Quick, before it’s too late!

"Call Magen David Adom, and tell them there’s a man here with hypothermia.” Yonatan handed his phone to Yanky. “And tell them to hurry.”

Yanky took the phone into his gloved hands. His heart was pounding in alarm. A cruel voice in the back of his mind whispered, So you wanted to see a yetzias neshamah, just once? Well, you’re about to see another one.

“Maybe we should rub his hands?” Bugi suggested.

“No,” said Yonatan. “That would only make it worse.” His personal trainer back in London was also a skiing instructor, and Yonatan remembered his stories about rescuing people lying injured in the snow. “If you rub the limbs, you bring the blood to the skin, away from the vital organs.”

Lulu’s face was gray and cold. “He’s dead,” Bugi gasped.

“He’s alive, I feel a pulse,” Yonatan said, and he sent Bugi to bring the blankets from Lulu’s stroller outside the fence.

“Do you think he’ll make it?” Yanky asked, pulling off the little backpack he was carrying and taking out the thermos Raizele had packed for him.

Yonatan shrugged slightly, his eyes intent on Lulu. “People have survived hypothermia before.”

Except for the ones who didn’t, thought Yanky, filling in the part his friend was leaving out. Gently, he nudged Yonatan aside and dripped a little warm, sweet tea into Lulu’s mouth. It would take the ambulance at least ten minutes to get here, the man on the phone had said. All their vehicles were out at the moment. Meanwhile, he’d been told, it was better not to move the victim, and not to try to warm the extremities… just like Yonatan had said.

Behind them, footsteps approached. Bugi was back at last with the blankets. Yonatan took them gratefully and sent Bugi to wait for the ambulance in the parking lot.

After tucking the blankets around Lulu with great tenderness, Yonatan gazed at the old, craggy face, at the dull gray hair, the blackened teeth, the gap where a tooth should have been. Unaware of the contortion of his own features, Yonatan gazed at this stranger, his uncle. Shalom looked much older than his sixty-two years. Dad looked so much younger, although they were exactly the same age.

Tell him. Right now. Say the words Dad asked you to say. Just say it! Quick, before it’s too late!

Yonatan was silent. Yanky dripped a little more tea between the dry lips. The delicate aroma of Earl Grey tea filled the bunker. Shalom was semi-conscious. His heart beat slowly, irregularly. Brownish drops of tea ran down his chin and disappeared into his matted beard.

“There’s something I have to tell my uncle.” Yonatan’s voice was faint. Yanky looked at him sharply. Behind the Ray-Ban glasses and the well-groomed exterior, something was boiling like lava in his friend. “Something my dad asked me to tell him. And I can’t make myself do it.”

“Something bad?”

“No. Something good — but I can’t. Even if you shout at me or hit me, Yanky, it won’t help. I just can’t get the words out.”

“Why would I hit you?” Yanky reached out. His black fleece glove gripped Yonatan’s dark gray, leather one. “Hitting and screaming never help anyone. I’ll just tell you this: You can do it, Yonatan. You can tell your uncle whatever it is you’re supposed to say.”

Ten seconds passed in fraught silence. Yonatan turned to the figure lying there in the bunker and spoke. “Uncle Shalom, it’s me, Yonatan. Do you remember me — your brother Sandy’s son? We’ve been searching for you. My father asked me to tell you…” Yonatan’s lips trembled. He bit them nervously. That family of his, they should only be well, all of them. Always sending him on impossible missions…

With one supreme effort, he pushed the words out. “He asked me to tell you that he loves you. Your brother loves you, Uncle Shalom. Can you hear me?”

“I won’t… go… to Sandy,” Shalom whispered between shallow breaths.

“You don’t have to go anywhere.” Yonatan reached under the blankets, into the sleeping bag, searching for his uncle’s hand. “You don’t have to see him if you don’t want to. My father loves you anyway. He loves you because you’re his brother, because you’re dear to him, and it makes no difference what you do, where you go, or what you wear. You don’t have to come to London, and he won’t make you take the yerushah if you don’t want it. Uncle Shalom, can you hear me?”

The eyes facing him were glazing over. As Yonatan held on to the wrinkled hand, the weak pulse grew even weaker. Bum-bum. Stop. Bum. Stop. Another faint bum. Was that a smile on the careworn face, or just an involuntary, unconscious grimace?

Yonatan’s phone rang. “Answer it, Yanky, please,” he said, not wanting to let go of Shalom’s hand. “If it’s Sara Baila, ask her for me if she booked tickets yet, and what time the flight is.

“My father’s not well, and we were planning to go see him,” he added in response to Yanky’s questioning look.

Behind his crisp demeanor, Yonatan was holding back tears. Where was that ambulance? How long did it take to drop people off at Har Hatzofim and get here? He and his friends had done all they could, and meanwhile this paralyzing cold was draining his uncle’s life away. How much longer could Shalom’s heart hold out?

Yanky took the call.

“Yonatan?” A woman’s voice, American-accented, hesitant.

“No, this is his friend. Yonatan asked me to answer for him. We found his uncle, he needs medical attention, and Yonatan is with him now. He wants to know if you’ve got tickets yet, and what time the flight is.”

“We won’t be flying to London.” Sara Baila’s voice was trembling. “There’s no need anymore… They’ll be bringing Yonatan’s father to Israel.”

And now Yanky had another impossible task — to tell Yonatan that he had no father, and never would.

♦♦♦

The next morning a pale sun rose, and soft snow wrapped Yerushalayim like a tallis.

There was a small, dismal funeral, with only the Chevra Kaddisha men and a handful of acquaintances in attendance, barely a minyan. The plan was to bury the niftar in a cavernous, multilevel underground cemetery, the kind of burial you get for free, courtesy of Bituach Leumi. But then it turned out that someone had bought a nice plot for him on Har Hamenuchos. The meager group made its way there, mired in snow. They buried him quickly, said Kaddish quickly, and left.

The other levayah set out that afternoon from the Shamgar Funeral Home, with crowds of people in attendance trampling the slick, icy pavement. There were delegations from many chassidic courts, board members of many charitable funds, executive directors of chesed organizations, and reporters from all the news media. The levayah passed the beis medrash, and all the bochurim came out to walk along in a show of respect for their departed benefactor. Distinguished men addressed the throngs, raising their voices in moving eulogies, sketching vignettes of Sandy Eliav’s boundless generosity, his lifelong pursuit of chesed.

This being a snow day, Raizele had stayed home with the children, and they were outdoors, creating “the best snowman ever.” It was a chassidishe snowman, of course, and they found some pieces of charcoal to tint his frosty shtreimel and beard, then placed an old pair of Yanky’s glasses on his nose. As they backed up several paces to view and admire their work, they heard footsteps behind them.

“Saba! Saba Schlossman!” The boys were jumping for joy.

Raizele’s father stood there, ice crystals clinging to his boots, his cheeks red from the cold.

“I was at Eliav’s levayah,” he said, “and I thought I’d come around to make sure you’re all right. Do you have enough bread and milk in the house, Raizele? Is the heat working?”

“Everything’s fine, Abba. I have everything, really.”

Her father smiled. “Everything, in terms of what?”

She smiled back. “In terms of everything, Abba.”

Leib Schlossman looked the snowman up and down and said they’d done a beautiful job. The boys went to look for a suitable umbrella for the frozen chassid, and Raizele’s father seized his opportunity.

“People have been coming up to me lately,” he said quietly. “Even today, at the levayah. They all want to know what’s with Yanky, where he’s holding these days. Is he in our chassidus, or not? Is he one of the watchmaker’s followers, or is he still searching? Because he does come to the beis medrash a lot, and you know how people are, they want to know what to make of it, what box to put him in. So what do you say, Raizele? What am I supposed to tell them?”

“Oh, Abba,” she said. “Tell them that he’s so much more than ‘a chassid, or not a chassid,’ ‘following the watchmaker or not following the watchmaker.’ Those labels are so superficial! What does it matter which building he goes to when he davens or where he eats shaleshides? All I know is, he has the Eibeshter in his heart. I know that for sure, Abba, and once I know that, I don’t need anything else.”

Her father had an expression that, like Yanky’s, was hard to define.

“Is that not okay, Abba?” she inquired. “Do you disagree with what I said?”

“I don’t just agree,” he said. “I’m very happy. I’m so happy for Yanky that he got a wife like you, Raizele.”

Yanky arrived home shortly after his father-in-law left. On the way back from the levayah, he’d picked up a newspaper. Its front pages were crowded with black-framed notices announcing, with great sorrow, the sudden passing of the esteemed philanthropist Reb Alexander Eliav, and the condolences of one institution after another to his family on the untimely loss of their husband and father, a man distinguished by his outstanding acts of chesed.

The aveilim, said the notices, would be sitting shivah until after Shabbos at the home of Reb Yonason Eliav, Rechov HaCarmel, Nachlaot. They also suggested that the niftar’s sons-in-law, his son (Harav hachashuv Yonason Eliav shyblcht”a, bara kre’a d’avuha) and the choshuve almanah (Maras Marta shetichyeh, eishes chayil ateres baalah) take comfort in the continuation of their distinguished husband and father’s worthy undertakings.

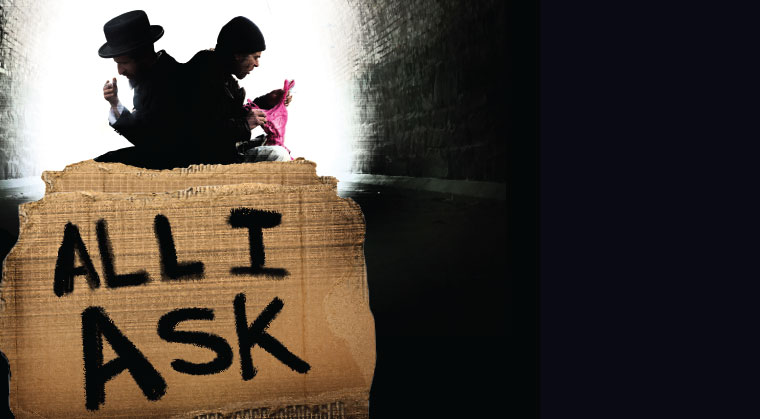

Nobody had written anything about Lulu. That was sad, thought Yanky, because he was a good man. No one eulogized him or sat for seven days talking about his integrity, his generous heart, and his graciousness toward his friends. No one knew about these things, and how would they know? They all thought he was just a street beggar schlepping around an old gray baby stroller piled up with bags of shmattehs.

At the back of the paper, on page 17, where all the companies posted notices about stockholders’ meetings, there was a short paragraph about a homeless man who was found lifeless at Givat Hatachmoshet in last night’s snowstorm.

But on Har Hamenuchos, where the snow was melting into rivulets of muddy water alongside two fresh graves, the disparity in the newspapers made no difference. Status and fame mean nothing, after all, when you’re touching eternity.

THE END

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 818)

Oops! We could not locate your form.