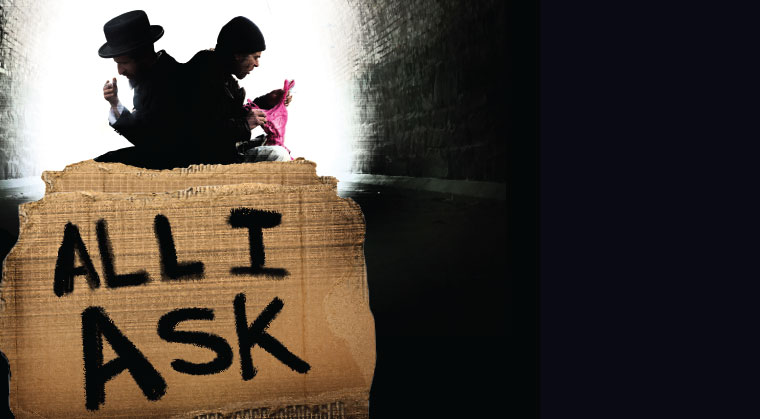

All I Ask: Chapter 57

"It doesn’t matter what seeds you’ve pecked at, or what spring you’ve drunk from. You will always be welcome in this house"

"I don’t get it, all those stories about Siberia,” Lulu grumbled to himself, as he tried to pull the sleeping bag more snugly around him. It was a good sleeping bag, thermal and water-repellant, and the wool coat was thick and well lined, but his feet were still ice-cold. He sighed, opened the sleeping bag, and got up to find another layer from the bundles on the stroller. He pulled out his trusty old comforter, zipped himself back into the sleeping bag, and spread the comforter on top. “How could anyone survive in Siberia where it’s 40 or 50 below zero?” he marveled grimly.

It may not have been Siberia, but the tunnel by the bus station was a veritable icebox. Lulu felt the cold wrapping itself around him like a snake. He got up once again, this time to look for his old army jacket. His teeth were chattering. Where was it? In that white bag from Miki’s Toy Store? Or maybe in the big black bag from the bargain store? Or was it somewhere among all the anonymous bags from the shuk?

The gloves on his hands were making it harder to search. He tried taking off one glove, but within seconds his fingers were stiff. He pulled the glove back on and continued rummaging. He was about to give up when he found the old coat at last.

With slow, clumsy movements, Lulu wrapped the coat around his feet, pushed his feet down into the sleeping bag, and closed the zipper once more. Again, he topped the whole arrangement with the comforter.

The wind outside was howling, tearing limbs from trees and sending corrugated roofs flying away from the balconies they were meant to shelter. In the tunnel by the bus station, under all those layers, Lulu rubbed his hands together and thought desperately about where he could spend the next few days. Nochum Kleiner’s brother-in-law’s father, he should live and be well, had finally gotten around to starting renovations today, of all days. Workers had showed up in the apartment that morning, filling the place with sacks of sand and cement and informing him that he had to leave, because they were about to start breaking down the walls.

Nobody had even thought to let him know ahead of time. He had to gather up his things and vacate the premises while the workers looked on, pitying but impatient. He had plenty of old plastic bags, and he stuffed his clothing and utensils into them, along with whatever food he had. One big, orange bag was crammed into the basket under the stroller, and four more were hung from the handles, two on each side. He folded his sleeping bag and comforter sloppily. Those went on the seat, and on top of them, the rest of the bags. The stroller rocked, threatening to collapse under its burden. Lulu tried redistributing the weight, but the workers had no patience. Lulu was forced out into the unknown.

He spent the next few hours in the vestibule of a nice shul on Rechov Shmuel Hanavi. It rained continually all morning, and the gabbaim apparently had compassion for him and didn’t ask him to leave. Around noontime the rain and wind let up a bit, and he made his way up Rechov Yechezkel, dragging his feet to the soup kitchen. He’d always been strong and healthy, and he remembered how he used to do this uphill hike easily. Now he was huffing, puffing, and stopping to rest every few meters. Apparently, his health wasn’t what it used to be.

At the soup kitchen, he sank into the nearest chair, at the first table. Wordlessly, a waiter he didn’t recognize put a plate of hot lentil soup in front of him. Lulu burned his tongue devouring it, and asked for more.

“We’re serving the main course now,” the waiter explained. “If you still want more soup afterward, you can have.”

The main course was wonderful. The schnitzel was pretty small, but the steamed vegetables were hot and well-seasoned. He took a forkful of pearl couscous in red sauce and rolled it on his tongue, enjoying it despite the burn. He had two portions of strudel for dessert, and then he lay his head down on the table and fell asleep. There was some rustling around him when the waiter rolled up the disposable plastic tablecloth and replaced it with a clean one. That didn’t bother Lulu. He went right on dozing there until finally, the manager came over and told him gently that he was sorry, but it was time to lock up.

Lulu stood outside the door, wondering what to do now. Should he go to Bugi? No. Well, maybe yes…. His self-respect won out in the end. He couldn’t keep forcing himself on Bugi’s hospitality all the time. “I can manage on my own,” he murmured to himself.

The evening found him in the underpass by the Central Bus Station, listening to the childish singing of the beggar with the grimy keyboard and suggesting other songs he might add to his repertoire. But then the beggar with the keyboard went away, and fewer and fewer people were passing through… and it was so, so cold!

“Tomorrow I’ll go to Bugi,” he rasped, huddling into the depths of his coat, his sleeping bag, and his comforter. “I’ll go there tomorrow. But only for one night.”

♦♦♦

The rolling window shutter, their defense against both the blazing sun and the chilling wind, was broken, and Rav Reuven Chaim hadn’t managed to get hold of anyone to come and fix it. The storm winds had done damage all over the city, and the handymen were overbooked. No one was going to make time to fix a single triss.

“Did you try calling Zechariah?” Yehudit asked her husband.

“Yes. He’s out of town.”

“What about Avraham?”

“He can’t find a spare minute. He might have time on Friday, he said. Maybe.”

“Hmm. How about what’s-his-name, from Shiputz Lakol?”

“They’re not answering.”

The Kleiners decided to try the yellow pages. This was a standard repair job, after all, and they didn’t need one of their tried-and-true men to do it. But they gave up before they got past the letter aleph. There seemed to be dozens of those, from Aleph-Aleph Feex-it to Aleph-Aleph-Aleph-Aleph Tikkunim — all booked for the next few days.

“I’m afraid we’ll just have to leave it like that, open all night,” Yehudit told Raizele as they chatted on the phone at lunchtime. “It’ll be cold, but we couldn’t get anyone to come.”

Ten minutes later Yanky was there, with Bentzi in tow. “Raizele called from work and said you’ve got a broken triss here,” he said.

“Really, Yanky, we didn’t mean to bother you with this!” his mother protested, as he climbed onto a chair, screwdriver in hand, and opened the wooden box that housed the rolled-up shutter.

“It’s my pleasure,” he replied, coughing as a cloud of dust enveloped him.

“If it can’t be fixed, then at least try to roll it down,” his mother said. “I’d rather have it stuck closed than have it open all the time, with this terrible weather.” She went to the kitchen, taking Bentzi with her, eager to spoil him with treats. Rav Reuven CHaim remained in the doorway to the bedroom, regarding Yanky thoughtfully.

Focused on his task, Yanky pulled the twisted belt of braided fabric away from the stuck wheel. It was tattered from years of use, and it crumbled between his fingers. He stepped down from the chair and bent over the tool box, looking for the new length of belt he’d bought at the hardware store on the way. He could feel his father’s eyes on his back.

What did you think, Tatty, when you heard I was going to the watchmaker? Were you afraid of losing me, the way you lost Yerachmiel Poiker 20 years ago? Who was it who told you, how did you feel, and what did you say? Do you understand that I’m on the right track now? Can you see how much happier I am?

Such were Yanky’s thoughts under his father’s gaze, but he gave them no voice. He loved his father and admired him no end, but to speak openly with him about this? He couldn’t.

“How’s it going by Rav Groinem?” his father asked. “Are they learning Hamafkid, same as us?”

“Yes,” said Yanky, checking the length of the new belt. “We’re up to ‘shlichus yad’ now, and listen to what one of the talmidim asked me — he’s Binyumin Brand’s grandson, you would love him, a very solid bochur. He said to me….”

Yanky carefully laid out the kushya and the various teirutzim the boys had offered. His father was enjoying the lecture, and he suggested a teirutz of his own. He went to the bookshelves in the living room and came back with an armful of seforim. He opened the Chazon Ish first, and read a passage aloud. Yanky abandoned the window shutter, peered at the Chazon Ish, and argued that the re’ayah didn’t fit.

“Do you have a Terumas Hakri?” he asked. “Because this boy Brand showed me something there….”

Rav Reuven Chaim looked at his vibrant, radiant son. He saw there was inner peace there, inner freedom to shine.

I was so afraid of losing you, Yanky. I was worried about you, and yes, I was a bit angry, too. How could you turn your back on the beautiful derech I chose for you? What do you think you’re doing, looking for other paths?

It took time until I learned to tame my thoughts and let you go, to trust you to look for whatever it was you were seeking. I was like a little boy holding his pet bird tightly, so it wouldn’t fly away. Such a beautiful bird, with such colorful feathers, shining in the sun. The boy has raised this bird from the day it was hatched. “How can I know if the bird is really mine?” he asks.

“Release it,” says his wise old teacher. “Relax your grip. Let it fly. And if it comes back to you, you’ll know it always was yours.”

The boy strokes the bird’s feathers one last time. He forces himself to loosen his fingers, to open his hand. The bird lingers on his hand for a brief moment, and then beats its wings. Such fine wings — the boy himself tended them day and night. He fed and nurtured this bird. It was he who enabled it to fly.

I released you, Yanky. I let you fly far from our nest, and I didn’t say a word. Your mother and I continued loving you, hosting you, and respecting you just like before. It was hard for us sometimes to keep quiet, but we kept our mouths shut. There were moments when sharp words almost pierced through the barrier, but we forced them back.

And suddenly, out of a bright blue sky, I see a little spot coming closer. The fledgling bird that flew away, cutting across the heavens, is coming back to us, full of life and joy. Its wings are spread, its path is steady.

Welcome home, my child.

And it doesn’t matter what seeds you’ve pecked at, or what spring you’ve drunk from. You will always be welcome in this house.

to be continued…

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 813)

Oops! We could not locate your form.