All I Ask: Chapter 19

“I haven’t made up my mind yet about this shiur. He has such an unconventional approach, and the people there aren’t really my type”

"Should I go to the watchmaker’s shiur? What do you think?” Yanky asked.

“If you find it interesting, then go,” Raizele said steadily, making sure not to betray how much she cared.

“I haven’t made up my mind yet about this shiur. He has such an unconventional approach, and the people there aren’t really my type.”

“Not your type, what do you mean? Not young and chassidish?”

“Sort of. It’s more like — I wouldn’t call them misfits exactly, but there are a lot of people who are on the margins. Not all of them, but a lot of them are these divorced guys living alone, or aging bachelors. Then there are a couple who are really unstable — like they could probably use some professional help. So I’m not sure I should make it a regular thing. It’s okay to go now and then — I’ve seen three or four guys who are more my type there; they drop in once in a while. But…”

“But what?”

“But I’m tired of coming and going where I don’t really feel I belong. I’ve had enough of running around from one mashpia to another, from one tish to another.”

“When were you running around? You never told me.”

“When I was a bochur, I used to go around sampling every tish in Yerushalayim.”

Raizele was quiet.

“Nu, so what do I do now about this rav’s shiurim? I don’t even know whether to call him a rav or a watchmaker.”

“If you want to go, go.”

“Why aren’t you trying to convince me?” Yanky probed.

“Because you’re a big boy, Yanky. You can decide for yourself.”

“All right, I decided. I’m going. I might stay afterward to talk with the rav a bit.”

Yanky went, and afterward he approached the rav.

“How are you?” the rav asked him.

“I have no more koach, and I’m sick of it all,” Yanky said quietly.

The watchmaker turned deep, dark eyes on Yanky. “And all through the day you’re thinking, ‘Ugh, now I have to go daven… ugh, now I’m fleishigs and I have to wait six hours… now I have to bite my tongue and not say what I feel like saying, and not think what I want to think….’ Is that how it is?”

“Pretty much.”

“But the Ribbono shel Olam says, ‘You’re making a mistake. You don’t have to do anything for Me. Mein teyere kind, you can do whatever you like, right now.’ ”

“Mah pitom?” Yanky blurted out. “I have to do the mitzvos, they’re not optional. I can’t just do whatever I want!”

The watchmaker smiled. “In the holy Torah,” he said, “the Ribbono shel Olam says to you, ‘I have placed before you life and good, death and evil. You’re not obligated to Me. You don’t do anything for Me. It’s all for you, only for you, only to bring you to that happiness you dream of day and night.’

Yanky listened quietly as the watchmaker continued. “Sometimes you think to yourself, ‘Nu, so I’ll suffer now in This World from all these mitzvos I have to do, but it’ll be worth it when I get to Gan Eden.’ And maybe that works in the short term, maybe it keeps you motivated for a few months, or a few years. But how long can you keep it up? Can you really carry a burden like that for 70 years, groaning and sighing, telling yourself that at the end you’ll get your reward? Of course you can’t. That’s why you’re so wrong, Yankele. You don’t have to suffer. Not for 70 years, not even for a day.”

“But I am suffering!” Yanky cried desperately. “And I do have to toe the line and do all the mitzvos, or else I’ll lose my place in my kehillah, my wife will take the children and run, and in the end I’ll burn in Gehinnom!” Tears ran down his cheeks, and he was ashamed of them, but had no intention of holding them back. He wasn’t going to live this way for one more second.

“How long has it been like this?” the watchmaker asked.

“Twenty-nine years,” Yanky said softly. “Ever since I was born, I’ve been taught to fulfill obligations, to obey orders, to do what I’m supposed to do. And that’s what I’ve always done, even if my heart wasn’t in it.”

“The chinuch in your chassidus is very good,” the watchmaker said softly. “I know your rebbe, and I know his approach. It brings excellent results.”

“Yes, I see those results all around me,” Yanky said sadly. “My brothers, my brother-in-law, my friends in kollel, they’re all following the rules, and they all seem perfectly content. It just goes to show that there’s something wrong with me. They’re all exactly what they were raised to be — disciplined, obedient soldiers. And they’re happy that way! They feel fulfilled. But I…”

“You don’t have to be a soldier, Yankele. You can’t be a soldier, in fact. You’re not cut out for that.”

“Then what am I supposed to be? A deserter?”

“Be a son, not a soldier.”

“And what about Gehinnom?”

“I don’t know. Here, we’d rather talk about Gan Eden. More than talk about it, we’d rather live in Gan Eden.”

“I want that, too.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.”

The watchmaker-rav gazed at him thoughtfully. “Well, then, shall we start from the beginning?”

♦♦♦

With the children in tow, Raizele went to her mother-in-law’s succah for a Chol Hamoed get-together with her sisters-in-law. Meir’s wife hadn’t arrived yet from Beitar, and in the meantime Tilla, the upstairs neighbor, came by to share a cake she’d tried for the first time.

“Come sit with us, Tilla,” Rebbetzin Kleiner said cordially.

“Thanks,” said Tilla, sitting down at once. She’d clearly been expecting to join them all along. “Yehudit, your succah is gorgeous, as usual. Ach, what a zechus, to sit in the tzila d’mehimenusa….”

“How are you, Tilla?” Yanky’s sister Chana Miriam inquired politely.

“I was fine, until I met Esther Poiker in the street a few minutes ago. You know about her son Yerachmiel, Rachmana litzlan. Nebach, it’s been 20 years already since he took off his yarmulke, and the woman hasn’t gotten over it. Just seeing her took away all my simchas yuntiff. I’m telling you, a few good whacks with a leather belt, that’s what that boy of hers should have gotten. Try the cake, please, it’s something special. My daughter-in-law gave me the recipe.”

“Do you really think hitting a boy with a belt could bring him back to Torah and mitzvos?” Raizele couldn’t help asking. Tilla stared at her in surprise.

“You have no idea how Esther and her husband spoiled that child,” she said. “He was the prince of the family. And how did he thank them? He gave them nothing but tzuris. Nothing but pain and anguish. To Los Angeles he ran away, he wouldn’t settle for less, the meshiggene.”

“It’s true, some people just aren’t mentally stable.” That was Rivka speaking up. “Like Chani Biernitz’s husband. I hear he’s going around in jeans and a red T-shirt. The poor woman.”

“Lashon hara,” Chana Miriam whispered.

“Lashon hara?” Tilla said, in full-throated indignation. “People like that are rebels, nothing less; the laws of lashon hara don’t apply to them anymore. All these resha’im who drag their poor families through the mud without a thought, without a care… just following after their taivahs…. Chani Biernitz should have demanded a get the day he started trimming his beard, that’s what she should’ve done.”

“And then he wouldn’t have gone off?” Raizele asked. “If she’d demanded a get at the very first sign, he would have done teshuvah and gone back to the straight and narrow?”

“He would’ve realized that he had to stop his nonsense!” Rivka decreed. “People like that are superficial, foolish, and thoughtless, and they make their families miserable.”

Raizele felt the succah spinning around her. Shape up or ship out — was that the philosophy here? Was there no compassion for anyone who couldn’t find his place within the narrow box of the chassidus? Was this how they’d be speaking of her Yanky one of these days — her thoughtful, considerate husband, the wonderful father of her children, a man with a delicate, sensitive soul still searching for its place? Would they be sitting, sampling the newest cream cake, wiping a stray crumb from their lips, and saying that Yanky was superficial and thoughtless?

“You don’t realize how unhappy they are,” she said quietly.

“Who? You mean their families — Biernitz and Poiker?”

“No, I mean the young men themselves.”

“Nu, of course they’re unhappy,” Tilla trumpeted. “They made public fools of themselves, running off to Los Angeles or Ramat Gan, expecting to find who knows what, and now they’re eating their hearts out, but they’re too ashamed to come back.”

“I don’t mean now,” said Raizele. “I mean before they go off. They went off because they were unhappy; they were suffering. They were going through things that are hard for us to understand.”

“What kind of suffering are you talking about?” Rivka asked. “A wonderful, supportive kehillah like ours all around them — that’s suffering? To act like a mensch and do the mitzvos, that’s suffering? That’s the greatest happiness a person can have!” She paused to help herself to another piece of cake. “The cake is excellent, Tilla.”

Raizele answered cautiously. “For you and for me, it’s the greatest happiness. But not everyone is the same. For some kids, our standard chinuch isn’t quite what they need, and the social pressure to be exactly like everyone else is too much for them. They feel like birds imprisoned in a cage.”

Chana Miriam looked a bit perplexed. “You knew Biernitz and Poiker?” she asked.

“No. I was only seven when Poiker left the yeshivah. I only heard about him now and then from my older brothers. With Chani Biernitz I have a passing acquaintance; she was in my grade. I used to see her in the halls, or at the Rosh Chodesh assemblies.”

“So how do you know about what’s going on inside the minds of the people who go off the derech, or are on the verge of going off?” This was Raizele’s mother-in-law, making her first contribution to the discussion.

“I don’t know,” said Raizele, keeping a straight face as she lied. “It’s just what I think, from watching the world around me.”

“Well, I think they’re just superficial people who live for instant gratification,” Rivka insisted. “They’re giving up eternity for the pleasures of This World.”

“And I think Raizele is right,” said Rebbetzin Kleiner, to everyone’s surprise. “At least in some cases. Yerachmiel Poiker, for example. He wasn’t a superficial person; he definitely wasn’t stupid. He was one of the brightest bochurim in the yeshivah. Your shver loved him heart and soul, and he used to learn with him a lot. But something went wrong.”

“I’ll never understand what’s the matter with people like that,” Rivka sighed.

“Me neither,” Tilla echoed.

You’ll never understand anyone, Raizele answered them inwardly. You look at everything from your own narrow perspective, and you’ll never entertain the possibility of looking at things any other way. Everyone is supposed to talk the talk and walk the walk, just like you.

Thankfully, someone changed the subject at that point. Two hours later, Raizele collected her boys from their game with their cousins and took them home. Yanky wasn’t back yet. She put the boys to bed, and they were too tired to object. She tidied up the house, and then sat down to read for a while. Yanky still hadn’t come home. Should she wait up for him, or go to sleep?

She decided to wait.

Around midnight the door opened quietly. Yanky came in, eyes alight, shoulders straight. They hadn’t looked so straight in a while, she realized.

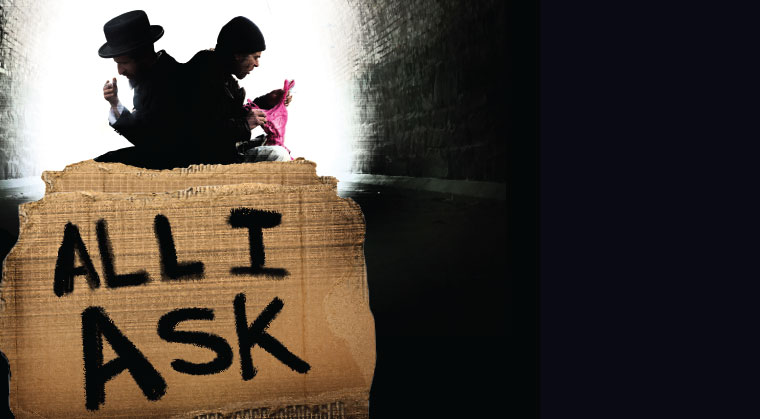

“Where’ve you been?” Raizele asked. He looked… different. Was he drunk? The thought frightened her. Was that it — his battery had gone dead, and he’d started drinking to wash away the pain, like that street beggar he’d taken to the hospital that summer night?

But he looked at her, and she saw that he was sober. Hyper-sober.

“I found it, Raizele,” he said. “It’s so different from what I thought, but it changes everything.”

to be continued...

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 775)

Oops! We could not locate your form.