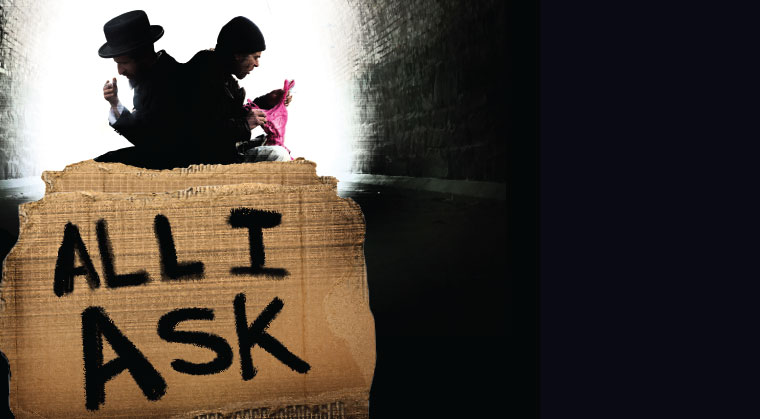

All I Ask: Chapter 11

"What you throw in the laundry, by us is called clean. Where’s the garbage bag with the laundry? We’ll find something in there that’s not too dirty”

T

he women had all gone to the water park at Chofetz Chaim early in the morning, and Yanky was left in charge of his boys until midday. Getting them through the morning routine was no problem; they woke up refreshed after sleeping well in the country air, and Raizele had packed their clothes in neat bundles labeled with each child’s name and organized by day of the week.

At 8:15, Yanky gave his boys a quick up-and-down glance and said, “It looks like we’re all ready. Come, let’s go to davening.”

A quick succession of knocks interrupted them just as they headed toward the door. Yanky opened it, and there stood Nochumku, looking harried.

“Maybe you’ve got a spare shirt for my Avremi?” he said. “I can’t find one for him in the suitcase. We brought a lot of clothes, but I guess all his shirts got dirty already. And it’s better Raizele shouldn’t know,” he added, after pausing for a quick breath.

“How can I take a shirt out without her knowing about it?” Yanky said. “She’s got everything organized by color, child, and day of the week.” Yanky took out one bundle and read the label: “Eliyahu, Thursday.” The next bundle was labeled “Nechumi, Thursday,” and the next, “Bentzy, Thursday.”

“But she probably packed a few extra shirts too,” Nochumku pointed out shrewdly. “How about lending us one of those?”

“We already used the spares,” said Yanky.

“So take one out of the laundry.”

“What?”

“What I said — take one out of the laundry. Davening starts in a minute, and half my kids aren’t dressed yet. You want Avremi to go to shul in pajamas? What you throw in the laundry, by us is called clean. Where’s the garbage bag with the laundry? We’ll find something in there that’s not too dirty.”

“There isn’t any garbage bag,” Yanky informed him. “We have separate bags for every category.” He opened the bag marked “Colored Laundry” and pulled out a slightly rumpled shirt in gray-and-purple plaid. Nochumku accepted it with thanks.

“This you put in the laundry?” he remarked over his shoulder as he hurried out. “Just because Eliyahu wore it for half a day? It’s perfectly clean!”

The boys had been following the conversation with amusement, and now Yanky hustled them out the door.

After a busy day spent learning and touring the cowshed, Yanky came home at suppertime to find three of Nochumku’s children seated at the table together with his own three.

“They were playing outside, and they didn’t know where their mother was,” Raizele explained to him quietly. “They were hungry, so I invited them to join us for supper.”

She’d already sliced raw vegetables, made omelets, and put out chocolate leben for dessert. Just as the kids were digging into the treats, a staccato beat sounded at the door — Nochumku’s signature knock.

“Are my kids here, maybe?” he asked.

“They are,” said Yanky.

“Rivka went to buy bread, we didn’t have enough left from breakfast,” Nochumku said.

”But we already had supper here,” chirped four-year-old Miri. “ ’Cuz we were so hungry, so Tante Raizele said we could come in and eat. Now we’re just having dessert.”

Nochumku picked up a chocolate leben and peered at it critically. “You buy Hameshek products?” he asked, addressing his brother.

“Why not?” said Yanky. “We’ve eaten their products since we were kids. And Machzikei Hakashrus is an excellent hechsher!”

“Oh, come on!” At this point it finally occurred to Nochumku to lower his voice. “You mean you don’t know about the big balagan there with Rav Billetsky?”

“I heard something about it,” Yanky said with obvious reluctance. “But I also heard that all the mashgichim are still there, and nothing changed as far as the kashrus standards. Whatever happened, it was only some sort of dispute at the management level, and it had nothing to do with kashrus or hiddurim. And please keep your voice down,” Yanky added in a whisper.

“By you in the kollel, does anybody bring leben from Hameshek?”

“How should I know? I don’t go around checking to see what leben they bring. Probably some guys stopped buying Hameshek. So what?”

“So I don’t know about you, but we prefer to be mehader in kashrus,” Nochumku declared. “We don’t buy anything that isn’t 100 percent.”

“Even if the kashrus is perfect, and your missing percentage points are only because of politics?”

“Children, it’s time to go home,” Nochumku announced, ignoring Yanky’s question. “No, you don’t need to finish your lebens. We’re going now. Yanky, please pass along our thanks to Raizele for helping out with supper — and also the W-2 forms.”

“What was that about help with the W-2 forms?” Yanky asked Raizele as soon as the door was closed behind Nochumku.

“This afternoon, on the way back from Chofetz Chaim,” Raizele said, “Nochumku’s wife was asking me about every possible way to get maximum gains from Bituach Leumi. If she could inflate the numbers on her salary reports, how much would she benefit, and what amounts would be best to put down on the slips, and when to start, and was it better to increase the sum all at once, on one slip, or to spread it out evenly, and so on.”

Raizele worked as a payroll accountant at a large accounting firm. Being responsible for some 1,500 pay slips, she was fluent in all the laws and regulations regarding workers’ rights and taxation.

“Did you answer her questions?”

“I told her technical facts. I don’t mind telling her things like how the employer’s tax percentages are calculated. But I avoided telling her the main things. I was too embarrassed.”

“What were those main things?”

“That Bituach Leumi started double-checking applications for maternity allowances in a chareidi neighborhood, after they discovered several false declarations of income. That a number of heimish employees have approached me, trying to doctor the figures on their W-2s so they could get a better deal on daycare or maternity leave. That my dati-leumi coworkers in the salary department were shocked to hear these things. They say that everyone who takes a shekel from Bituach Leumi under false pretenses is robbing all the rest of us.”

“These people say that it’s not so bad to play around with state funds; the state withholds so many benefits that we really deserve anyway.”

“Let them bring a psak din, signed and sealed. They won’t be able to get one. You have to understand, Yanky. If Bituach Leumi has to spend more than expected on these allowances, it’s going to come out of their budget for other things. You and I will pay for these lies. The same thing with the daycare centers: If some people are paying less than their fair share, others are forced to pay more, or to get less, because there’s less money in the public coffers. And even if Rav Ploni Almoni, who wishes to remain anonymous, told them they could play with the facts to get the money they really deserve, who gave them a heter to falsify their declared income?”

“So when employees come asking you to play with the numbers for them, do you do it?”

“Absolutely not. My company has a strong management, and there’s no way we can change the figures on salary forms once the data’s been entered. But I’ve heard from colleagues who work in other companies that sometimes they’re pressured into playing around with the numbers.”

Suddenly they heard people talking outside. Yanky glanced out the window and saw his brother, his brother-in-law, and several other avreichim out on the grass. Nochumku was holding forth on the subject of Machzikei Hakashrus and the Billetsky Affair.

“I’m going out for a minute,” Yanky told Raizele, and he slipped out the door.

“Anyone who buys those products is machzik yedei ovrei aveirah!” Nochumku was proclaiming, just as Yanky joined the circle.

“Anyone who cheats Bituach Leumi is doing an aveirah of his own,” Yanky spat out.

“What?” Five pairs of eyes stared at him in surprise.

Yanky’s cell phone began to ring. He ignored it.

“We’re not talking about Bituach Leumi,” Nochumku explained patiently. “We’re talking about Rav Billetsky. What went on there was completely indefensible, you realize? You can’t remain silent in the face of chillul Hashem.”

“Yanky!” Raizele was at the window, calling him. This was not accepted decorum; she never interrupted his conversations with his brothers, this must be an emergency. “Yanky! Yanky! Come home for a moment, please, I need you here urgently! I tried calling your phone, and you didn’t answer!”

Alarmed, Yanky ran, taking the three steps leading up to their lodgings in one quick movement.

“What’s wrong?” he panted, closing the door behind him. Looking around wildly, he saw no sign of emergency. “What was all that embarrassing scene about?”

“About getting you away from there.” Raizele bolted the door.

“Well, I’m going right back out there,” he said. “And I’m going to tell Nochumku once and for all what I think of a man who neglects his children, cheats Bituach Leumi, and insults me in front of my family. He’s going to get a piece of my mind. Because of stupid politics and ego problems, he stops buying Hameshek leben, and he thinks that makes him into some big tzaddik.”

“You’re not going out there.” She stood blocking the door. “I’m not letting you.”

“Then I’ll shout out the window at them. I’ll make sure they hear what I really think of Nochumku.”

“You will not shout at them. You will not speak your mind. There’s no one there who’s willing to listen, Yanky.” When she saw the look on his face, she added sadly, “The people around us think buying Hameshek leben is a worse aveirah than lying, stealing, and insulting people. That’s how their minds work. What will you get out of arguing with them? Do you want them to think you’re a rebel? If I’d known all this stuff about the hechsher, believe me, I would have just bought Tnuva leben.”

“Maybe you’re right,” Yanky said bitterly. “Maybe I should add one more wonderful hiddur to the million things I’m already makpid about — not to buy Hameshek products, at least as long as we’re here with all the rest of my family.”

“Nochumku’s Avremi was davka dressed nicely today,” Raizele said suddenly. “He was wearing a shirt in the same gray-and-purple plaid that I bought for Eliyahu. I wonder where Rivka bought it.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 767)

Oops! We could not locate your form.