All I Ask: Chapter 1

A

few advertising circulars lay on the white sofa. Yanky turned the pages absentmindedly until his gaze focused on an ad for a milchig fish restaurant.

“What do you want with restaurants?” Tzvika gave him a quizzical look. “Just yesterday that rich guy what’s-his-name, Goldenkrantz, gave you a feast fit for Shlomo Hamelech.”

“What do I want with Goldenkrantz and his feasts?” said Yanky. “I’d rather pay for my own meal than feel like a chesed case.”

Tzvika’s eyes opened wide “A chesed case? That’s a good one. Don’t worry —Goldenkrantz didn’t feel a dent in his pocket from that meal. You don’t realize what kind of rich we’re talking about. I’m just a minnow in the pond compared to him. To him, paying for a spread like that is like throwing a coin to the beggar by the Central Bus Station.”

“Thanks for the delightful comparison,” said Yanky, tossing the circular onto the coffee table.

“What, you’re insulted?”

“No… I just thought your phrasing was a bit inappropriate. My father is a little more respectable than a street beggar.”

“I respect your father more than you do, and you know that, Yankele.”

“Nobody could respect him more than I do!”

“Okay, it’s not a contest. Tell me about Goldenkrantz’s gourmet spread.”

“Well, the appetizer was cut fruit with some special sauce, and these crackers —not crackers, really, more like thin wafers. Arranged all fancy, of course on these diamond-shaped plates.”

“Sounds nice.”

“The next course was smoked salmon roses with broccoli salad on the side. That was on a square plate, with three little triangle-shaped bowls of different dressings.”

Tzvika groaned. “A meal like that, wasted on people who can’t appreciate it! They should’ve invited me instead of saintly tzaddikim like your brother Nochumku and that holy brother-in-law Feivel.”

Yanky grinned. “Nochumku didn’t know where to start eating, and the holy Feivele didn’t even look at his salmon, he just swallowed it like it was gefilte fish. As for Meir, I don’t know… he never gives you a hint of what he’s thinking. Twenty-nine years I’ve been his brother, and I still can’t say I know him.”

“What about the Rebbe? And your father?”

“My father spent most of the time talking in learning with Meir and Nochumku, and the Rebbe came at the end, as usual. He washes, has a bit of bread, gives a little derashah —starting with his gratitude to the host, of course, and bentshes with us.”

“So why does Goldenkrantz spend so much money feeding you?”

“Because Feivele is the Rebbe’s son, so he’s choshuv. And me and my brothers — well, we’re the Rebbe’s mechutanim, so we’re choshuv by marriage. Plus, our father’s the biggest mashpia in the chassidus — that’s also pretty choshuv. So Goldenkrantz figures he makes a seudah for us every Rosh Chodesh, maybe he’ll be choshuv, too.”

Tzvika felt the bitterness in Yanky’s words. “Don’t go all nebach on me, Yanky. I meant, why does Goldenkrantz order a meal at a hundred dollars a plate for the Rebbe, who comes in at the end and eats a k’zayis, and for your father, who can’t tell the difference between rib-eye steak and grilled chicken?”

“Or for Nochumku and Feivel, who can’t tell the difference between tilapia and gefilte fish?”

“Exactly.”

“Maybe it’s for me.” Yanky spoke in a measured tone. “For HaRav HaTzaddik Reb Yankel Kleiner, the beloved ben zekunim of HaRav HaTzaddik Reb Reuven Chaim… who likes good food and good wine.”

“I like good food and wine, too,” said Tzvika. “And it’s not like I’m wallowing in guilt about it. You, on the other hand…”

“That’s because you’re not the son of a mashpia, with everybody expecting you to live on some higher spiritual plane,” Yanky said.

Tzvika was about to retort — something sharp and clever — when he noticed the pain in Yanky’s eyes. He closed his mouth instead. For a long time, neither of them spoke.

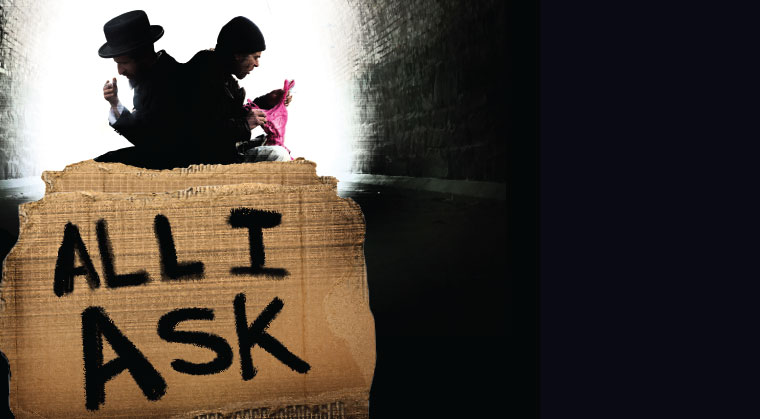

There were lots of people at the Central Bus Station on Sundays, but that didn’t necessarily mean business was booming. The Sunday people were typically in a hurry, on edge, and most couldn’t spare a few seconds to put a coin in Bugi’s sawed-off soda can.

Lulu’s little soup bowl wasn’t doing any better that Sunday. Most of these stingy people were tossing him ten-agorot coins, if anything.

“What did I get up early for?” Bugi grumbled. “I could’ve slept in until 12, like Avery and Musa.”

“Early! The guy gets up at ten, and he calls it early!” Lulu’s laugh was loud and rough, but good-hearted. “If I were your papa, I’d wake you up at six and teach you to be a mensch.”

“We’ve been sitting here all day, and we haven’t even made minimum wage,” Bugi went on lamenting. “You want to go find another place?”

“It’s too hot to schlep around. Let’s just stay here and wait for our mazel to change.”

Their mazel came in the form of a young tourist, who emerged from the station and turned to the people lined up to pass security. “Pardon me,” he said in British-accented English. “Uh… Hotel Avital?”

“Avital? It’s out on Highway Number 1, next to the Eitz HaZayit,” someone answered in Hebrew.

“No,” said a man in his fifties. “There’s a Novotel out there by the Eitz HaZayit. This gentleman is looking for the Hotel Avital.”

“Yes, Avital,” the young Briton confirmed.

The older man crinkled his forehead. “That would be in the hotel district on Derech Rupin. Near the Ramada. It’s not far, but how do I explain to you how to get there…?”

“He needs to take the 68 or the 69 and get off at Rupin,” said a passing teenager, stopping to join the little knot of impromptu guides.

“He should take a taxi,” said a security guard. “That way he’ll be dropped off right at the hotel.”

“You’re wrong, all of you,” Lulu called out. No one even turned to look at him.

“Adoni! Mister!” Lulu was shouting now, trying to get the tourist’s attention. “These guys don’t know what they’re talking about. Hotel Avital is right here on Rechov Yafo, a few meters down the street, near Machaneh Yehudah.”

“What?” The Englishman looked at him for a moment. If he was repelled by the man’s scruffy appearance, he was too well mannered to show it.

Lulu repeated his directions in English. But his rivals were having none of it.

“Im takshiv lakabtzan hazeh…” the elder of the group began, and then paused to translate his words. “If you’re going to listen to this beggar, you’ll get nowhere.”

“He’s crazy, you know?” a young man chuckled, gesturing at his forehead with a circling finger.

Bugi, looking up from his cardboard-box-turned-seat on the sidewalk, knew the truth. The men on line were wrong, and Lulu was right — and not only because Lulu knew Jerusalem like the back of his hand, but simply because Hotel Avital was there by the shuk, and there was nothing to argue about.

But Bugi didn’t speak up. Let them all say what they wanted, what did he care?

Now the tourist was listening to an energetic young man. No, he didn’t want to take a bus, he wanted to walk on his own feet in the Holy Land. So then he should walk to the Chords Bridge and turn left onto Herzl Boulevard, and in a moment he would see all the hotels.

The tourist nodded and thanked him, shouldered his backpack, and started walking.

By 6 p.m., another thousand people had passed through the gates of the Central Bus Station, and Bugi had enough money for a falafel wrapped in a big laffa. He considered whether to stay and collect a few more shekels for a coke, or to make do with tap water.

“I’ve told you a thousand times, go to Mordechai,” Lulu chided him. “You can melt his heart with a sob story. Just tell him your mother died and your saba is sick, and he’ll give you a bottle of Coke for free and knock a few shekels off the price of a laffa, too.”

“You go to Mordechai and tell him horror stories,” Bugi retorted, ready for a fight. “I’m not a liar or a beggar. I buy only what I have money to pay for.”

“Not a beggar! Hahahahaatchooo!” Lulu’s laugh exploded into a sneeze. “Did you fellows hear that? He says he’s not a beggar! That’s a good one, Bugi. I didn’t know you had such a sense of humor!”

“I’m not a beggar,” Bugi insisted. “It may be my job right now, because I have to make ends meet somehow, but it’s not who I am.”

“What’s wrong with being a beggar?” said Musa, who was following the conversation with interest. “We’re all beggars here, and we’re all fine people. Where else can you find a group like ours, people who’ll do anything for a friend and aren’t ashamed to do whatever they need to make an honest living?”

“And you’re not stam a beggar,” Avery chipped in. “You’re homeless! That’s a whole different level.”

“I’ll get past it one of these days.” Bugi was adamant. His long hair clung to his sweaty forehead. Maybe tomorrow he’d buy some scissors in the two-shekel store and give himself a haircut. “One of these days I’ll be rich. I’ll rent an apartment and have a job….”

“You have a job now, too!” someone from the group piped up.

“I’ll have a proper job, and maybe even a family. You’ll see.”

“Well, it’s nice to hear that somebody here’s got some dreams,” Lulu said graciously.

“Sounds more like pipe dreams to me,” Musa huffed. “Once you’re stuck here, you can’t get out. You’ve got a homeless soul, Bugi. You couldn’t sleep in a normal bed, on a nice thick mattress, if you tried. You’d feel like you were lying on nails, and you’d get up in the middle of the night and come running back to us.”

Bugi listened to the prophecies with a half smile on his lips. He knew a day would come, and when that day came, he’d be a new person. He just didn’t know when that would be.

***

At six thirty, a familiar figure approached them. It was that tourist again, only now he was perspiring heavily and looked weary.

“I owe you an apology, sir,” he said to Lulu in his accented English. “You were right about the hotel not being there. I should have listened to you before. Would you please give me the right directions now?”

“The hotel you’re looking for is on this street, Rechov Yafo,” Lulu said, completely disregarding the apology. “Just walk straight alongside the tram tracks until you get to the Machaneh Yehudah station.”

“Thank you, sir,” said the young man, pressing a folded bill into Lulu’s hand.

“Hey, mister, what about us?” Musa and Avery clamored.

The tourist gave each of them, too, a note in pounds sterling, but his gaze was still focused on Lulu. “Here’s my business card,” he said, offering Lulu a light-blue card. “Hang on to it.”

“Lulu, give him your card too!” Avery roared. “When Heaven sends you a rich friend like that, you don’t send him away empty-handed. Just a moment, mister, Lulu’s gonna give you a lovely business card!” Avery tore a corner off from a stray newspaper, then dug into his bundles for a pen.

“Certified Donation Collector,” he wrote in a curly script underneath Lulu’s full name. “Central Bus Station, Rechov Yafo, Jerusalem.”

“Thank you,” the tourist said politely as Avery thrust the scrap of paper into his hand, although he didn’t really get the joke.

“Tishmor al zeh!” Musa called after him. “Lulu, tell him in English to keep it.”

Bugi had been watching the scene as though paralyzed. “Save it!” he called out suddenly.

“I will,” the young man said in his polished English.

And then he was gone.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 757)

Oops! We could not locate your form.