A Plague on Their House?

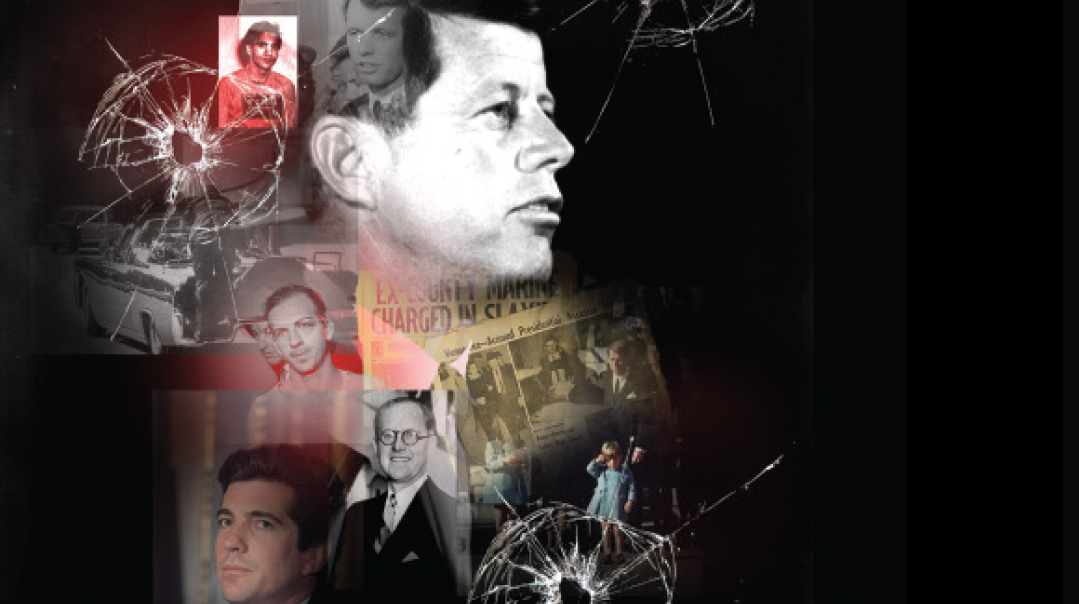

| September 29, 2020Some people call it the “Kennedy Curse.” But does that mean a series of coincidental tragedies over the decades, or an other-worldly campaign targeting the progeny of one of the most powerful men of the last century?

A family with a long and influential history in American politics, the very name “Kennedy” conjures up images of wealth, power and presidency — at least one Kennedy family member served in federal elective office in every year from 1947 to 2011. But early on, tragedy began to strike, and it wasn’t long before the Kennedy name also became synonymous with calamity and misfortune. Disaster varied from murder to plane crashes, drownings to skiing accidents, and catastrophic illness. While there are still several prominent members of the Kennedy family in the public eye today, luck and good fortune seem to have disappeared from their lives long ago, replaced by tragedy affecting immediate family members, spouses, and even the families of spouses and friends.

For decades, there’s been much speculation about what’s come to be known as the “Kennedy Curse.” Is it all coincidence, or is there really something “bigger” that has haunted the family and taken its vengeance on the children and descendants of businessman Joseph P. Kennedy Sr.?

***

“What do you want me to do, crack up an airplane?” Senator Ted Kennedy asks with a grin.

“Nope, just parachute out of it into the convention,” his travel coordinator, Ed Moss responds.

It’s 1964, and 32-year-old Kennedy is campaigning for reelection to the Senate for Massachusetts. The state’s democratic convention is scheduled for that night, and as they head to catch their flight of out Washington, Kennedy and his aide wittily debate pulling off a spectacular entrance.

Notwithstanding a warning of bad weather and rolling fog, Moss engages pilot Ed Zimny to fly a chartered Aero Commander 680 twin-engine aircraft to Barnes Airport in Westfield. Senator Birch Bayh and his wife are soon seated in the aircraft along with Kennedy, as Bayh is the convention’s keynote speaker. The aircraft soars skyward soon after 8:00 p.m. After three hours of uneventful flying, Zimny radios the Barnes control tower that he’ll attempt an instrument landing in the zero-visibility conditions.

In the course of managing the campaigning in western states for his brother John’s 1960 Presidential run, Ted Kennedy had learned to fly. Now, as he sits in the Aero Commander, his gaze is fastened on the instrument panel. He watches intently as the altimeter sinks from 1,100 to 600 feet. To his horror, there is no glide which transforms into a bumpy but safe landing. Heart-stopping skidding along the treetops ensues instead. Then comes the bone-shaking impact. They have collided with a tree.

Bayh is brought back to consciousness by his wife’s screams. His dazed gaze flits over his startling surroundings. Cracked branches tangle with airplane wreckage. Leaves mingle with gore. The plane lies crumpled in an apple orchard, its belly slit open as though a knife has sliced through it. Zimny and Moss are clearly dead. His eyes rest on Kennedy. Bayh realizes that he’s trapped. With a burst of adrenaline, he lugs Kennedy, who is no lightweight, under his arm and out of the shambles.

Kennedy is soon sprawled on a Northampton Cooley Dickinson Hospital bed, undergoing an urgent blood transfusion. He has three crushed vertebrae, a punctured lung, broken ribs, and a profusion of internal bleeding. When the worst is over, he faces the discomfiting news — he must brace himself for a five-month recovery within the rigid confines of a Stryker frame bed.

When the news hits the press, Reporter Jimmy Breslin interviews Robert, Ted’s older brother.

“Is it ever going to end for you people?”

Bobby gives the reporter a serious answer, “If my mother hadn’t had any more children after her first four, she would have nothing now… I guess the only reason we’ve survived is that… there are more of us than there is trouble.”

“It’s a curse,” Ted’s wife Joan tells her sister-in-law Jackie Kennedy, the fresh widow of JFK, who was assassinated the year before. “Look at the things that have happened. Can we just chalk it up to coincidence?”

Later, Robert, accompanied by federal investigator and family friend Walter Sheridan, visits Ted in the hospital. “Somebody up there doesn’t like us,” Robert tells him.

Cutthroat Tactics

Since the death of Joe Jr. in 1944, the first son of nine Kennedy children, the Kennedy family history has played out like a tragic drama. And it all began close to a century earlier when the SS Washington Irving docked in Boston on April 21, 1849, and Patrick Joseph Kennedy, a 26-year-old cooper from Wexford, Ireland, disembarked. Escaping the Irish Potato Famine, the impoverished cooper hoped to build a new life on American soil with his wife Bridget. His dreams materialized, and ten years on found him the father of five, with steady work in his trade — but then he passed away from cholera.

The youngest of the five Kennedy orphans was Patrick Joseph, nicknamed PJ. Quick and ambitious, he earned his first wages in his mid-teens as a stevedore on Boston’s dock. By the time he hit his twenties, he owned several saloons popular among the local Irish working class and married the daughter of a well-to-do saloon keeper.

Wealth didn’t satisfy PJ, although he had it in abundance. His thirst for politics prodded him to peddle influence by handing pro-bono liquor to anyone who could help him rise in the Democratic party. Free drinks were evidently a good place to start, as his journey wound up with five consecutive terms in the Massachusetts’s House of Representatives. Two terms in the state senate followed.

A wildly successful simultaneous stint in the world of finance assured PJ that his son, Joe, and his three younger sisters would grow up with all the perks of wealth. Joe didn’t have to go to work, but he was an ambitious teen who decided to occupy his time with work in a haberdashery. He was later known as no lover of Jews, but at that time, he spent part of his Friday nights as a Shabbos goy lighting coal stoves for the local Jews.

Tall and athletic with piercing blue eyes, Joe’s academics were terrible, but his street smarts prevailed. His father’s connections and a sly bottle of whiskey presented to his teachers when his grades slumped ensured that he was well on his way to a prestigious university.

Harvard beckoned, and Joe began his studies, envisioning a future in banking. “Win at all costs,” was his father’s motto, impressed upon him from childhood. He was determined to do so, despite the world of banking being dominated by New England “Brahmins,” his social and cultural superiors. With his father’s help and his own sheer guts, at age 25 Joe could boast of becoming the country’s youngest bank president.

Studying the laws of finance not only transformed Joe into a financial whiz, but also educated him how best to break those laws. A streak of corruption was his by birthright — one of his earliest memories was hearing one of his father’s campaign aides bragging, “we voted 128 times today.”

Joe’s tactics and strategies were cutthroat, but his sins soon came home to roost. Family interests were suddenly under attack and he was forced to borrow frantically from his sisters for a succession of risky stock investments. They all suffered when the money disappeared, but Joe somehow succeeded in floating to the top again. He even went on to make a respectable match, marrying Boston’s Mayor Honey Fitzgerald’s daughter, Rose, and in staunch Catholic tradition, they settled down to build one of the century’s most historic families.

The First Omen

From the time Joe Patrick Jr. was a kid, Joe groomed this firstborn of his brood of nine to become president of the United States. Already at his birth, the mayor of Boston declared to the media, “This child is the future president of the nation.”

The young man himself was wholly invested in this goal, boasting that he would be voted in without “aid” from his father, who was then the 1st Chair of the US Securities and Exchange Commission.

After graduating high school, Joe enrolled in Harvard, where it became clear that he had inherited more than his father’s go-getter personality. He had adopted his prejudices as well. Despite having helped the local Jews when he was a teenager, Joe Senior had developed into a virulent anti-Semite. Later, he would casually blame the Jews for their persecution by the Nazis, stating “They brought it on themselves.” Now, with Hitler’s recent rise to power, he thought it would be a good idea to send his firstborn to Berlin to view the Führer’s policies first-hand.

Not only was Joe Jr. enthralled by Hitler’s mode of government, enthusing, “Hitler is building a spirit in his men that could be envied in any country,” he also heartily approved of his “sterilization” policy. In a letter to his father, he praised it highly as “a great thing” that “will do away with many of the disgusting specimens of men.” He mitigated his viewpoint slightly by describing it as “excellent psychology,” and the need, for propaganda reasons, to create a “common enemy… the Jews.” He added, “It is extremely sad that noted professors, scientists, artists, etc. should have to suffer, but as you can see, it would be practically impossible to throw out only a part of them, from both the practical and psychological point of view.”

Joe Jr.’s plans to run for the US House from Massachusetts’s 11th congressional district were derailed by war. He left Harvard before completing his final year and enlisted in the US Navy, refusing his father’s offers for a nice, safe desk job. He was deployed to Britain, where he became a member of Bomber Squadron 110. By 1944, he had completed 25 combat missions and was eligible to return home. Instead, his adventurous spirit drove him to volunteer for another stealth mission.

“I am going to do something different for the next three weeks,” he wrote home. “It is a secret, and I am not allowed to say what it is, but it isn’t dangerous so don’t worry.”

“Joe, don’t tempt the fates,” his father replied. “Just come home.”

Operation Anvil involved an unmanned aircraft, wired with explosives, dispatched to an enemy target in southern France and deliberately crashed. The booby-trapped aircraft bombers couldn’t take off on their own, but were instead flown into the air by a crew of two, who would parachute out after activating the remote-control system and arming the detonators.

Joe’s adventurous streak pushed him to take the challenge. When he was on the verge of climbing into his aircraft, Ensign John Demlein tossed a question at him: Is he all caught up with his life insurance payments?

Joe flashed a toothy Kennedy grin. “I’ve got twice as much as I need,” he responded.

Eighteen minutes into the flight, Joe and his fellow crewmember set the aircraft on autopilot and watched in satisfaction as it made its first remote-controlled turn. They removed the safety pin, and the explosive went live. Joe radioed the agreed code phrase “spade flush,” informing control that they had completed their final task before they bail-out.

“Spade flush” turned out to Kennedy’s final words. Unbeknownst to the pair in the cockpit, they were trailing an ugly streak of black exhaust as they flew. Two minutes later, a pair of deafening explosions ripped the sky, belching acrid smoke and flame. The bomber had detonated prematurely, killing Kennedy and his comrade instantly.

When Joe Sr. heard the news of his son’s death, he drowned his pain in Beethoven, although he saw listening to classical music as an unmanly sign of weakness. As he mourned, he vowed that his dream of a Kennedy son rising to the Oval Office would not die along with Joe.

The Anvil disaster was an example of the Kennedy adventurous streak. Joe Jr. could have easily decided to return home, and at that point, there was nothing unusual about a risk-taker’s life ending in such a way during a world war. But he was just the first. Many more tragedies were on the horizon.

Another Crash

Six years before, in 1938, after persistent pleading with FDR, an elated Joe Sr. became United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom. Once ensconced in London, the second Kennedy daughter, Kathleen, popularly known as “Kick,” became involved with William John Robert Cavendish, the future Duke of Devonshire. But at the outbreak of war, a terrified Joe surreptitiously sent his family home immediately — booking them on separate travel accommodations so as not to make a public demonstration of American fear.

Kathleen, still anxious to marry Cavendish, eventually wangled her way back to England in 1943 as a volunteer for the Red Cross. The wedding was a quiet one, taking place a mere two days after the engagement was officially announced. Five weeks later, the couple were dismayed to hear that Cavendish had been ordered back to active duty in Belgium.

The news of Joe Jr.’s death arrived while Kick was still eagerly waiting for word from her new husband. She had barely dried her tears when the painful news shattered her anticipation. Cavendish had been killed by a sniper’s bullet. In the space of a month, the 24-year-old lost her brother and her husband.

Four years on, Kick found solace in a new fiancé, Earl Peter Wentworth-Fitzwilliam. He was a dubious character, but she was enraptured nevertheless. She planned to visit the French Riviera with her new groom and then take him to meet her disapproving father. They chartered a ten-seater de Havilland Dove for the occasion. During a stopover and a lunch with friends, a violent storm blew up. Both the pilot and the navigator informed the couple that the next leg of their journey would take them through the eye of the storm, and it would be prudent to wait it out before taking off again. Kick and Fitzwilliam threw caution to the wind and persuaded them to take off anyway.

The eye of the storm soon loomed. Approximately one hour into the flight, radio contact was lost. Twenty minutes of severe turbulence ensued, tossing the small aircraft up and down as much as several thousand feet at a time.

When the pilot finally cleared the clouds, he stared through the windshield. The plane was in a steep, dangerous dive. They were moments away from impact. Instinctively attempting to pull up had disastrous repercussions. The stress of the turbulence, coupled with the sudden change of direction, tore loose one of the wings, followed by both engines and finally the tail. The plane’s fuselage spun into the ground, coming to rest nose down in a ravine.

The next morning, rescuers traversed the mountainous Rhône-Alpes region, some two hundred miles from Cannes, to reach the wreckage of the plane. There were no survivors. Joe Sr. was mourning again.

Years later, when more tragedies befell the family, people began to figure Kick’s untimely death into the count. Was this indeed the second installment of the curse? Isolating the incident though, is it not reasonable to assume that a couple who chooses to fly through the eye of a raging storm, despite warning from those more experienced, are likely to meet with disaster? Similarly, the death of Kick’s first husband was no different than that of hundreds of paratroopers suffered in the Flanders. On the day he died, dozens of others died along with him. Every soldier who enters active duty knows what he’s risking.

But a public eager for gossip and prone to speculation wasn’t convinced. Something was going on with the Kennedys.

Fateful November Day

In August 1963, the odds of the four-pound, ten-and-a-half-ounce baby surviving were only fifty-fifty, yet the Boston Globe optimistically predicted, “He’s a Kennedy — he’ll make it.”

Jackie Kennedy, wife of President John F. Kennedy, Joe Sr.’s second dashing son, prematurely gave birth to a very little boy. Named Patrick Bouvier, the infant suffered from hyaline membrane disease, a lung disorder common in preemies. Despite the optimism in the press, the president, who had rushed to his side after missing the emergency birth, gazed at the infant in the incubator with a beating heart. It didn’t look good. He stood by helplessly as a team of doctors fussed over the child, urgently trying to revive him. After a while, they solemnly stepped back.

The president was devastated. His wife had not even been given the opportunity to embrace their newborn.

“He was genuinely cut to the bone,” Larry Newman, a Secret Service agent, remembered. “When that boy died, it almost killed him too.”

Three months later, the Kennedys were on their way to Texas. It was a significant trip politically, designed to smooth out kinks in the state’s democratic party. It would be Jackie’s first public appearance since baby Patrick’s death. An 11-mile motorcade route was planned to convey the vibrant pair through the streets of Dallas.

“I don’t want the bubbletop on the car,” JFK informed the aide organizing their schedule. The 1961 Lincoln Continental convertible, painted presidential blue metallic, had undergone security modifications worth $200,000. Surely those precautions were sufficient.

November 22 dawned with a drizzle which was soon dried by a radiant sun. Seated in the limo, the presidential couple were accompanied by Governor Connally and his wife. All four were in great spirits, the ladies loosely holding rose bouquets and the men wearing face-splitting smiles. As the excited Texans cheered, Mrs. Connally turned in her seat to face the president. “Mr. President, you can’t say Dallas doesn’t love you,” she smiled.

That morning, Lee Harvey Oswald had slept late. Grabbing a lift to his job at the Texas School Book Depository from a coworker, he dragged a long package along with him. When the driver asked him what it contained, Oswald’s reply was: “Curtain rods.”

Once at work, he figured out when the drive-past would ease into his gun-sights. He had soon found his perch and positioned his rifle.

After hearing the first shot, Roy Kellerman, the special agent in charge, whirled around to see what happened. Before he could process the scene, two additional shots had rung out, and JFK slumped into his wife’s lap.

The specialists at Parkland Memorial Hospital took one look at the stricken president and realized that it was over.

“Look at this head injury. We didn’t have any chance to save him,” a doctor confided to an attending chaplain.

By that time, Joe Sr. was 75 years old. He had seen his dream for a presidential son materialize, and had in fact almost single-handedly run his campaign. But since 1961, when he had suffered a debilitating stroke, he had been basically incapable of speech beyond “Yaaah” and “Nooo.” At the news of the death of his pride and joy, he released a long, wailing “Noooo.” His hopes had been shattered again.

Out of the 44 US presidents to date, four have been assassinated, and 17 have undergone assassination attempts, including one in which JFK himself was targeted. While vacationing in Palm Beach, Florida in 1960, JFK was threatened by Richard Paul Pavlick, a 73-year-old former postal worker. Pavlick intended to crash his dynamite-laden 1950 Buick into Kennedy’s vehicle, but changed his mind after seeing Kennedy’s wife and daughter.

Was Kennedy’s assassination just one more part of the statistic, or a link in another, more ethereal chain?

The Fourth Child

In the Jewish world, many believe that the “Kennedy Curse” began during the Holocaust. There are several versions of the story, but the most popular is that Rav Aharon Kotler had asked Joe Kennedy, who had President Roosevelt’s ear, for assistance in obtaining certificates for European Jews and to help lobby the president to work on saving them. Kennedy, a rabid anti-Semite, refused, and Rav Aharon cursed him that he should never see joy from his descendants. Other versions attribute the curse to Rav Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, the previous Lubavitcher Rebbe, or to the Ponevezher Rav. Still others speculate that the curse comes as a result of one of the Kennedy ancestors profiteering from the slave trade.

Modern Jewish historians, however, say the “frum” version of the curse is just urban legend. But curse or not, what is clear is that over the years, America’s golden family lost its luster, and what was originally viewed as an unfortunate conglomeration of bad luck steadily came to be seen as a propensity for tragedy — or perhaps, a dark curse. As episode after tragic episode piled up, it became increasingly difficult to dismiss the losses as misadventures or miscalculations.

And the tragedy wasn’t only about death. In 1941, after years of daughter Rosemary Kennedy suffering from mood swings, seizures, and violent outbursts, Joe Kennedy secretly arranged for her to undergo a prefrontal lobotomy, which at the time was thought to be a promising treatment for various mental illnesses. Instead of curing Rosemary, the procedure — soon after discredited — left her mentally and physically incapacitated. Rosemary remained institutionalized in seclusion until her death in 2005.

In other family tragedies up to that point, in the 1950s, Ethel Kennedy’s parents (Robert Kennedy’s in-laws) were killed in a plane crash in Oklahoma, and Ted Kennedy himself barely survived the fateful plane crash in 1964 that killed the pilot and one of his aides.

As episode after tragic episode piled up, it became increasingly difficult to dismiss the losses as misadventures or miscalculations.

And then came the murder of Robert F. Kennedy.

While his brother JFK had been in power, Robert (“Bobby”), the third Kennedy son, had been the Attorney General of the US. After the assassination, as one of his adversaries put it, he was “just another lawyer.”

But being a Kennedy, this prediction of anonymity was doomed from the get-go. The now vacant vice-presidency winked, and the public was enthusiastic about having another Kennedy in office to perpetuate JFK’s name. Lyndon Johnson, the former vice-president and now incumbent president and presidential candidate, disagreed. He disliked Bobby and appointed Senator Hubert Humphrey as his running mate. Undeterred, nine months after his brother’s death, Bobby was in the running for New York senator. With that in his pocket, the 1968 presidential election was his expected next move.

Joe Sr., his hopes now invested into his number three, was satisfied with the adult Bobby had become. He believed him to be “hard as nails” and more like himself than any of his other children. Rose felt differently, seeing him as kind and loving. The American people were similarly divided over his character assessment: Judie Mills, a Bobby biographer wrote, “His parents’ conflicting views would be echoed in the opinions of millions of people throughout Bobby’s life. Robert Kennedy was a ruthless opportunist who would stop at nothing to attain his ambitions. And Robert Kennedy was America’s most compassionate public figure, the only person who could save a divided country.”

After some back and forth, Bobby, father of 11 children, set out to do just that. After scoring major victories in the California and South Dakota primaries on June 4, he addressed his supporters at the Los Angeles Ambassador Hotel. With a concluding, “So my thanks to all of you, and now it’s on to Chicago, and let’s win there!” Bobby escaped the crowds through the hotel kitchen.

A slight, dark-haired man dressed in blue slipped in among the kitchen staff. Inside a rolled-up Kennedy poster he concealed a .22-caliber loaded pistol. Extending the weapon at Bobby, he squeezed the trigger. The presidential candidate stumbled. Twenty-six hours after the shooting, Bobby was pronounced dead.

The background for the assassination might have been related to Robert Kennedy’s admiration for the Israelis and his advocating for the sale of advanced F-4 Phantom jets to Israel in the wake of the 1967 Six Day War. His pro-Israel stance was what probably got him gunned down by an Arab in what could be considered the first act of domestic terror on US soil.

The murderer, Sirhan Bishara Sirhan, openly admitted his guilt, but his subsequent imprisonment was no balm to the aging patriarch’s soul. Joe Sr. appeared crushed, in a wheelchair, as Ted, his last remaining son, delivered a smooth speech expressing his gratitude to the nation for their condolences.

How many American parents can boast that two of their kids were presidential candidates? The Kennedys were society high-fliers and political overachievers. Was Bobby’s death part of the Kennedy jinx? Or is it more sensible to suppose that if another American family also bulged with presidents, presidential candidates, and senators, their death toll would be equally high?

End of the Road

It was 1969, and 81-year-old Joe Sr. was clearly seeing his end. After the stroke eight years earlier, Joe could still communicate and shuffle around with a cane. But now he’d lost his appetite, his eyesight, and his ability to breathe without a respirator. The man whose mantra had always been “Win at all costs” and had paid and charmed his way into the halls of political power, now lay helpless.

People surrounded him, and had he been conscious, each of them would have reminded him of another personal tragedy.

Jackie stood nearby, a living symbol of the greatest Kennedy misfortune of all — the assassination of JFK. And then there were other personal losses: Aside from the infant death of baby Patrick, she had given birth to a stillborn baby, Arabella, several years before.

Joe’s daughters, Patricia (“Pat”), Jean, and Eunice gazed at their stricken father. The presence of the three girls not only emphasized the absence of their older sister Kick, but also that of the next Kennedy daughter, Rosemary, still suffering and locked away by that ill-fated lobotomy that Joe himself had ordered.

Ted, the only Kennedy son alive, had been his father’s lifeline for a while now. Joe Sr.’s nurse, Rita Dallas had declared “Mr. Kennedy seemed to exist for only one thing — the sound of Teddy’s footsteps.”

But Ted’s life too, could not be taken for granted. He had almost gone the same way as his brothers — twice. The first time, he had scraped out of plane crash by the skin of his teeth. And earlier that summer, he accidentally drove his car off a bridge on Chappaquiddick Island, Massachusetts, resulting in the drowning death of 28-year-old passenger Mary Jo Kopechne. He had managed to escape the drowning vehicle but failed to alert the authorities about Kopechne’s presence until the next morning. The resultant scandal was mortifying (and although he served at a Massachusetts senator for four more decades, until his death in 2009, the Chappaquiddick debacle always haunted him, hindering his chances of ever becoming president). In his televised statement a week later, the senator said that on the night of the incident he wondered “whether some awful curse did actually hang over all the Kennedys.”

Now, as Ted leaned close to say a few words to his father, Joe failed to recognize his voice.

The children stood in a subdued semi-circle around the Kennedy family patriarch’s bed. They represented his dynasty, and the perpetuation of his name and values. But they were also shattered with yawning gaps in their ranks. A shadow of a pride that once was.

A Legacy of Pain

Incredibly, the “curse” did not end with Joe’s death. 1975 brought with it the demise of Jackie’s elderly second husband, Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis. Before his death though, he suffered the loss of both his son and daughter, faced severe business downturns, and the failure of his own health. “I was a happy man before I married her,” Onassis once said. “Then I married Jackie, and my life was ruined.”

Jackie’s trials continued after her second husband’s death, when her son, John, bearer of his deceased father’s name, met his end in a plane crash off the coast of Massachusetts in July 1999. He had been piloting the plane, carrying his wife and sister-in-law as passengers. They too met their deaths.

Bobby’s wife Ethel also suffered her share of trauma. In addition to losing both her parents in a plane crash, in 1973 two of her sons were in a jeep accident. Joe, the driver, escaped without a scratch, but David Anthony and another passenger were injured. David Anthony “collided with the curse” again when he passed away in 1984 from a drug overdose. Thirteen years later, his brother, Michael LeMoyne, perished in a skiing accident in Aspen, Colorado.

2012 brought Ethel the news of her former daughter-in-law Mary’s suicide on the grounds of her home in New York. In 2019, her granddaughter, Saoirse Roisin Kennedy Hill, died of an accidental overdose. A disastrous canoe trip last April, on Chesapeake Bay, resulted in the deaths of Maeve Kennedy McKean, another of her granddaughters, together with her eight-year-old son, Gideon.

Ted’s branch was also not spared. His son, Ted Jr., contracted bone cancer at age 12, resulting in the amputation of his right leg. In 1982, Ted’s wife, Joan, divorced him (she never remarried), and although he remarried in 1992, his own questionable morals became a target of gossip columnists and paparazzi. In 2006, his son, Congressman Patrick Kennedy, drove intoxicated into a barricade on Capitol Hill (he survived). In 2011, his daughter, Kara, died of a heart attack while exercising in a Washington DC health club.

But before suspecting a gremlin in the works, it’s worth considering the rate of misfortune suffered by other celebrities. A life in the public eye breeds all kinds of insecurities and dissolution, with drugs often being the go-to fix.

In addition, risk-taking and recklessness has also always been a part of the Kennedy culture: “They fly their own single-engine planes when they could afford a crew of airmen. They ski without poles on the hardest hills of Aspen on the last run of a December afternoon. They coax their way into the military in hopes of facing combat. It is and always has been the Kennedy way,” Boston Globe reporter Brian McGrory wrote, after John Jr.’s death in 1999.

Joe Sr. built a family designed to be perpetual headline news. And while other families may go through similar tragedies — heart attacks, infant mortality, business downturns — they suffer without the exposure.

If there was indeed a curse put on the Kennedy clan some would say that Joe Sr., bent on grooming his family for ultimate prominence at all costs, brought it on himself. He passed on a legacy of loose morals, dubious and cut-throat business practices, and anti-Semitism, although the latter two were not inherited by all of his children.

But even if the idea of a curse sounds far-fetched, looking at the bigger picture, it seems as if the script goes beyond the simple logic of circumstance. Whether a curse, Divine retribution or mere happenstance, as Robert told the federal investigator in 1964, “Somebody up there doesn’t like us.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 830)

Oops! We could not locate your form.

Comments (1)