A Bond Sealed in Blood

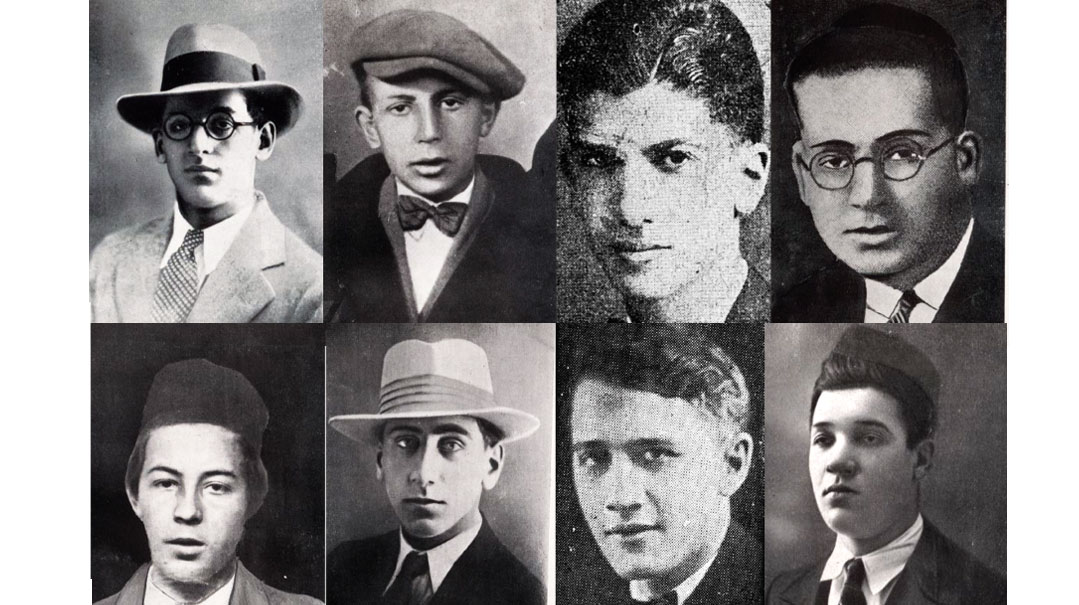

Of the 24 students of the Slabodka yeshivah murdered in the Chevron massacre, eight of them were Americans. This is their story

They were the first group of American yeshivah bochurim to go learn in Eretz Yisrael, but this wasn’t exactly the chavayah that yeshivah and seminary students seek out when they come to Israel nowadays. It was the 1920s, and, thirsting for an authentic Torah experience, they traveled to the dusty, ancient holy city of Chevron from cities as far as Seattle, Memphis, Philadelphia, and Chicago, an often-harrowing voyage on the various trains, ships, and even donkeys required to transport them to their final destination. It was a journey back to another era, to connect with a timeless legacy.

There were several dozen of these “Yankees,” with names like Benny and Dave and Billy and Jackie, who joined together with the lions of Slabodka after the yeshivah moved from Lithuania to Eretz Yisrael in 1924. Their European-born counterparts were seasoned talmidei chachamim, personalities like Reuven Trop, Yaakov Moshe Leibowitz, Mordechai Schulman, Chaim Zev Finkel, and Yitzchok Varshover (Hutner), to name a few. It wasn’t just an ocean that separated the two groups, but vastly different cultures.

But Torah is the great unifier, and so is, unfortunately, hate and destruction. Just five years later, the entire yeshivah, along with the Jewish community of Chevron, was evacuated following a horrific pogrom on Shabbos morning, parshas Eikev (August 24), 1929, in which 67 Jews were slaughtered and close to a hundred others injured and brutally maimed. But what many don’t know is that of the 24 students of the Slabodka yeshivah murdered in the massacre, eight of them were some of these young American talmidim.

Five days after the massacre, on August 29, a group of venerated roshei yeshivah and rabbanim met at the offices of the Agudath Harabbanim at 136 East Broadway on the Lower East Side, in what was one of the most prominent Torah gatherings ever to take place on American soil. Muffled sobs could be heard around the room, as the floor was ceded to a venerable pair of visiting senior European gedolim, Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz and Rav Shimon Shkop. Presiding over the gathering was Slabodka Rosh Yeshivah Rav Boruch Horowitz, who had arrived in the US to seek financial support for the Lithuanian branch of the yeshivah, along with Rav Eliezer Silver, president of the Agudath Harabbanim. Among the many other dignitaries in attendance were Rav Yehuda Levenberg, rosh yeshivah of New Haven, Rabbi Yosef Konvitz, chief rabbi of Newark and a son-in-law of the Ridbaz, and Rabbi Dov Aryeh (Bernard) Levinthal, chief rabbi of Philadelphia. Slowly, the stifled cries turned to loud sobs as the program commenced:

“Arzei Halvanon, Aderei Hatorah… Eight of our dearest sons were taken in the prime of their lives… Kedoshim, tehorim…”

There was to be a taanis tzibbur followed by 12 days of mourning, where special tefillos would be said and members of the Agudath Harabbanim would travel the country addressing memorial gatherings in various communities. A fund was set up to assist the refugee families of Chevron and a task force was formed to travel to Washington to petition the White House for better protection of the Jews of the yishuv.

The following week in Vienna at the Knessiah Gedolah of Agudas Yisrael, Rav Meir Shapiro made a siyum on maseches Zevachim as part of the first daf yomi cycle. He then addressed the crowd, saying, “We just finished learning about korbanos and [referring to the kedoshim of Chevron] we hope that we’ve seen the last of Klal Yisrael’s korbanos. Now as we we start learning Menachos, we pray that we’ll have menuchah — tranquility — from all of our troubles.” Rav Meir cried as he spoke, and there was nary a dry eye in the room at the end of the siyum.

American Standard

While the Chevron yeshivah was strongly rooted in the world of Slabodka mussar, its links to America ran deep. In fact, it was during a 1924 fundraising trip to the United States that Rosh Yeshivah Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein created the framework to uproot part of the yeshivah and move it to Eretz Yisrael.

Prior to their departure back to Europe, a large farewell dinner was hosted in honor of Rav Moshe Mordechai and his colleagues on this US fundraising mission, Rav Avraham Yitzchok Hakohen Kook and Rav Avraham Duber Kahana Shapiro (the Kovno Rav). Spirits were high and Rav Moshe Mordechai was asked by the organizing committee if he was pleased with the results of the trip. He smiled and nodded in the affirmative, but they were a bit taken off guard when he told them there was something else they could do for him:

“It would make me happy if you could help me establish a yeshivah similar to the one we have now in Slabodka in the city of Chevron, in our ancient homeland,” he told them.

They agreed, and so began the unbreakable bond that was formed between US Jewry and the first Lithuanian yeshivah in the Holy Land.

Obviously, Rav Moshe Mordechai’s pioneering proposal didn’t come out of the blue. There had been a change in the Lithuanian draft law, which placed the yeshivah students in danger of being conscripted into the Lithuanian military. This was something to be avoided at all costs, and the yeshivah’s hanhalah, as well as its draft-eligible talmidim, panicked. This in turn led to a series of frenzied discussions, culminating in the revolutionary decision — as well as the realization of a life-long dream of the Slabodka Rosh Yeshivah — to settle in Eretz Yisrael.

In the end, Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein left Lithuania for Eretz Yisrael to lead the new branch of the yeshivah in the city of Chevron, and Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel, the Alter of Slabodka, followed some time later. The branch in Slabodka was to be headed by Rav Baruch Horowitz (Rav Moshe Mordechai’s brother-in-law) and Rav Isaac Sher (Rav Nosson Tzvi’s son-in-law), who remained in Europe.

It was a man named Harry Schiff who would become the yeshivah’s most important lay leader. Born in Minsk in 1869 as Ephraim Schlifkowitz, he immigrated to the United States in 1888. He initially tried his fortune as a peddler on the Lower East Side, moved to Texas for a few years, and upon his return to New York around the turn of the century, he developed a distressed real estate portfolio into a large collection of hotels and apartment buildings.

Schiff’s seed donation of $15,000 made the move to Chevron possible, and as chairman of the American Committee for the Hebron Yeshiva, he made at least three trips there during its almost five years in existence. In 1927, he organized a group of 15 influential American Jews for a solidarity mission to Chevron who raised additional funds so that the yeshivah could accommodate more talmidim and eventually purchase a large building of its own.

Meanwhile, Rav Moshe Mordechai returned to the United States, spending over a year crisscrossing the country, from New York and Los Angeles to Tulsa, New Orleans and Seattle. Influential New York Judge Otto Rosalsky organized a posh dinner for deep-pocketed donors who each paid $100 to attend. Jewish media figures such as David Galter of the Philadelphia Exponent as well as Gedaliah Bublick and Peter Weirnik, editors of popular Yiddish newspapers in New York, helped to publicize the visit. More than 50 rabbinic Slabodka alumni committed to raising funds from their congregations, while Mrs. Necha Golding of New York, helped establish a yeshivah sisterhood. At a time when the ideals of Zionist settlement were gaining in popularity in America, a familiar yeshivah deciding to settle in one of the four holy cities in the Land of Israel seemed to be a very relatable cause. It was taken up as well by Mizrachi leaders such as Rabbi Meir Berlin/Bar Ilan (youngest son of the Netziv) and Torah Vodaath founder Rabbi Zev Gold.

But raising funds wasn’t Rav Moshe Mordechai’s only goal. He visited RIETS in New York, HTC in Chicago, and the nascent New Haven yeshivah, after which he wrote to the Yiddishe Tageblatt: “I was amazed to see here, in America, a heileger yeshivah filled with gold and diamonds. I saw young men, great in Torah, studying diligently, devoted with the totality of their souls to growing higher and higher in understanding Torah…”

It was during that trip that he recruited many young Americans to join the yeshivah, boosting the total to more than 30 — a pioneering group that eventually would make up close to 15% of the yeshivah’s student body.

Seeing a European gadol who knew kol haTorah kulah, who knew the entire Talmud by heart, had a profound impact on the American boys. In fact, Rav Moshe Mordechai’s nephew Harry Epstein, an earlier Chevron talmid who acted as his traveling secretary and translator for much of the 1927 journey, recalled in a 1986 interview how “in every spare moment, he would study the Talmud — he used to study a minimum of seven folios of Talmud a day. Every Simchas Torah he would make a siyum and complete the whole Talmud, and every month, all of the Mishnah… I saw him many times on a train. There weren’t any lights and he couldn’t read, so he’d say it by heart. He knew the Talmud by heart — just like you can see everything on the palm of your hand, that’s how he knew the Talmud.”

For These I Weep

Sefer Zikaron L’Kedoshei Yeshivas Chevron, KedosheI Av Tarpat Yizkor Book, To Rise Above by Rabbi Dov Cohen, Lamdanut, Mussar Yeeliṭizem: Yeshivat Slabodḳah M’Lita L’Eretz Yisroel by Shlomo Tikochinski, Slabodka Archives, Author’s Personal Collection, Oral Interviews, Various Newspaper Clippings

Who were these American talmidim in Chevron, whose sojourn in Eretz Yisrael was so tragically, brutally cut short? With the help of Yizkor books, Slabodka archives, newspaper archived clippingsticles, and personal interviews with family members, I’ve gathered correspondence and information that have helped to provide a more complete picture of the individual martyrs and their stories. Perhaps at first glance, these boys seemed like run of the mill all-Americans, but delving a bit more into their lives, their depth, sensitivity, and spiritual strivings become apparent.

Their names were William (Zev) Berman of Philadelphia; David (Aaron Dovid) Shainberg of Memphis; Benjamin (Bennie) Hurwitz and Wolf (Zev) Greenberg of Brooklyn; and Aharon David Epstein, Harry (Tzvi) Frohman, Hyman (Chaim) Krasner and Jacob (Yaakov) Wexler, all from Chicago. Hashem yinkom damam.

For Benjamin (Benny) Hurwitz, studying in Eretz Yisrael was a dream come true. His father, Raphael Hurwitz, was born in the town of Meitschet, where he joined his famous cousin Shlomo Polacheck — “The Meitscheter Illui” — in the Volozhin yeshivah. In 1901, he and his wife, Esther, immigrated to the United States, where his textile business saw great success. Benny’s maternal grandfather, Rav Moshe Eliezer Gavrin, was one of the founders of RJJ, and that’s where he began his Torah education. He subsequently continued his studies at RIETS, where the Meitscheter Illui was then rosh yeshivah. As his parents always had a desire to live in Eretz Yisrael, in the summer of 1927 he accompanied his mother and two sisters to Petach Tikvah, where his father hoped to join them once the business was in order. Benjamin commenced his studies at the local Lomza Yeshivah before transferring to Chevron in 1928. By the summer of 1929 his family had decided to head back to America, but Binyamin was now a “Chevroner” and was not quite ready to return. The last letter he wrote to his father was penned less than three days before the attack, on Wednesday night, August 21, 1929, and described the events leading up to the massacre:

“Terrible, terrible, terrible. How terrible are the happenings that occur daily in Jerusalem, our Holy City in our Holy Land… There are attacks on the Jews, the government ignores them, …and the world is quiet… We hoped to build our land and the land has become transformed into a country for the English. We hoped to set up a just country and it has become the opposite.

“There are three fronts in which the Jews are pitted against the English and the Arabs. In only one of these have the Jews been successful. This is in the area of autonomy. When the English attempted to wrest control of internal affairs, both the Jews and Arabs objected so strenuously that the English gave up on the idea… For example, they appointed a brutal, Jew-hating officer to be in charge of the access for Jews to the Western Wall. On Yom Kippur, he restricted access. On Lag B’omer he beat a Jew. Thirty witnesses to the beating came to court and the presiding judge stated there was not sufficient proof to indict him. Can you imagine, 30 witnesses are not enough! Have you ever heard of such a thing, that 30 witnesses are not sufficient proof in a court of law?

“The second front is the antagonism of the British government to the building of a national homeland. This was discussed at length at the Zionist Congress in Zurich. The government has not kept its promise as regards the land. They give land to the Arabs but the Jews are forced to purchase whatever land they need for educational and health purposes…

“The third front is Arab vs. Jew. The main problem which disturbs the Jewish and Arab minds and which causes the arguments between them is the question of the Western Wall. On Yom Kippur of this year it all started. The English could not wait three hours until the sun to set and they had to desecrate our holy place on this holy day…

“But still, all was quiet until about two months ago. The Arabs began to realize that the Jews could manage without upsetting the status quo, but the Arabs started to build. They built a new gateway near the Western Wall, they opened a doorway so that they could disturb the Jews, and they declared that the status quo pertained only to the Jews and not to them. The Jews protested, but to no avail… Last Thursday, youth from the Trumpeldor legion rallied against the government regarding access to the Western Wall. They marched to the Wall and decried the Zionist leaders for their weak stand. But they did not hit or even touch anyone. The next day the Arabs rallied too… They marched out of the New Gate and hit Jews in the midst of prayer, tore up prayer books, and removed the notes that had been placed in the crevices of the Wall. The British police did nothing, not only that but they did not even permit the Jews to approach the Wall to pray. And this is the status quo?! Then the British issued a statement that equated the two protests!

“On Shabbos there were many attacks on the Jews by Arabs. One young man was stabbed and died that night. Then on Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday, there were more attacks on the Jews in various places and the British did nothing. The daily bulletins relate terrible occurrences. Jews are hit, they complain to the British police who ignore them, although at times they incarcerate the Jew who was hit and free the Arab who attacked him. This is the situation…

“The Jewish community in Eretz Yisrael is terribly agitated, and, especially in Jerusalem, the condition is bad. AND WHO KNOWS WHAT TODAY WILL BREED? Last night I returned to Chevron and today I went back to Jerusalem to pick up the passports, I have mine and I sent Mother hers… According to their plans, they will arrive in New York on October 17. They could not leave earlier because she has many things to arrange… I know you think they have left here already, but I am informing you that they will be here another three weeks. Man makes his plans, but if God decrees otherwise, there is no response.

“Your son who cries over the destruction of our Holy Temple,

Benjamin”

The letter was received days after Benjamin was savagely murdered trying to protect women and children in the home where he was killed. In Benny’s honor, his shattered parents established a memorial scholarship award in Yeshiva University that is still active today. They also opened their large summer home in Far Rockaway (then a resort area) to yeshivah students who would spend their summer vacations away from the stuffy city air. Having the yeshivah bochurim around gave the family a measure of comfort.

For Aharon Dovid Epstein, the path to Chevron wasn’t so far. He was the nephew of Rosh Yeshivah Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein, and his father, Rav Ephraim Epstein, was an influential Chicago rav and staunch patron of his brother’s yeshivah. In 1922, his son Harry became the first American citizen to travel to the Slabodka Yeshivah in Lithuania, and was among the first group to transfer to the new Chevron branch.

Aharon Dovid, however, didn’t seem destined to follow in his brother’s footsteps. The popular Hebrew Theological College (HTC) graduate commenced his studies at the prestigious University of Chicago in the fall of 1928 — but sometime that winter, he had a change of heart and told his father that he wanted to travel to Chevron immediately. He grew tremendously during the half year that he spent at Slabodka. The letters he wrote to his parents were filled with elevated sentiments and were evidence of a 17-year-old mature beyond his age:

“I’m already here in Chevron for a while, and all this time seems like a brief moment. When one learns, the entire world appears good and beautiful. Slowly, the fear of Hashem is entering my heart. It is so good to wake up every morning and know that it will be an interesting day, because it will bring a person closer to Hashem.”

In a letter dated 7 Iyar he wrote,

“The new (summer) zeman began, and I enjoy every day more and more. I feel that even the walls of the yeshivah store spiritual treasures. Many times I think how lucky I am for meriting to be in this holy place. Several times I dreamed that I returned home to America and I cried that I wasn’t able to stay longer in Chevron, and when I awoke I was very happy to realize that the yeshivah had a tremendous impact on me.”

He ended the letter with, “Your son, who is awakening from the dream state he was in all the days of his life.”

A month later he wrote to his father:

“While I was in Chicago, I did not understand how wrong it was to harm someone in thought and speech. But when I’m here, I feel how careful one must be about his fellow’s dignity. I’m learning that one must carefully weigh and measure every word that comes out of his mouth. There are those who are careful about what they say only occasionally and only then they will talk nicely about his friend. But I strive and work on myself to watch everything I say and to make sure that I don’t hurt anyone’s feelings. I see the Chofetz Chaim, the great tzaddik of the generation as my ideal role model…”

As a man whose life was rife with tragedy, losing three children during the course of his lifetime under various circumstances, one can only imagine the pride and joy Rav Ephraim felt upon reading these letters. Just a few weeks later, while many of his friends traveled to the coast for their summer vacation, Aharon Dovid Epstein chose to stay in Chevron to catch up on his learning ahead of the upcoming zeman. The 17-year-old was brutally murdered in the home of Chevron community leader, Eliezer Don Slonim.

Zev Greenberg was determined to have a Jewish education. Born in Kamenetz-Podolsk, his family immigrated to the United States following the difficult years of World War I. His brother had gone missing fighting in the Russian army, never to be seen again. Arriving in 1921, his parents enrolled Zev in public school, but as he reached bar mitzvah age he yearned to attend Torah Vodaath. His application was rejected because of his limited Torah knowledge, but Zev was persistent and refused to take no for an answer, ultimately drawing the attention of one of the rebbeim who promised to take him under his wing. He spent two years in Torah Vodaath, before transferring to the Yeshiva of New Haven. It was there that he began to dream of going to learn in Chevron, but his family’s financial situation precluded that possibility and it seemed doomed to remain a fantasy. Undeterred, he took on an early morning newspaper route, arising before dawn so he could complete his work before Shacharis, and began to save up money for the trip.

Eventually word of this bochur’s dreams and determination reached supporters of the Chevron yeshivah, who committed to a multi-year scholarship for him. There he joined Chaim Krasner, another Torah Vodaath alum who was learning in Chevron. He only spent a few months at the yeshivah before that Shabbos morning, when he was dragged out of the Kitzelstein house while attempting to defend his housemates. The frenzied mob began stabbing him with a vengeance, his blood staining the streets of the holy city as he cried out his final words of “Shema Yisrael.”

Tzvi Frauman was an inspiration, even as a young bochur. Born in Hamilton, Ontario, his family eventually moved to Chicago, where on the occasion of Tzvi’s bar mitzvah, his father took him to Rabbi Yaakov Greenberg who would be his rebbi at HTC and told him, “Until now I looked after my son, now I’m placing him in your care until he graduates filled with Torah knowledge.” Bu the time he graduated (as valedictorian), he’d already completed several masechtas in Shas.

After the massacre, Rabbi Greenberg related to the authors of the Yizkor book, “America has not yet produced a native-born rosh yeshivah of its Eastern-European counterpart who has mastered both Talmud Bavli and Yerushalmi, Poskim, Rishonim and Acharonim. Tzvi made it his goal to become the first American-born yeshivah student to reach this level. And he was relentless in trying to reach this monumental goal. He wanted to go learn in the great Torah centres of Lithuania or Poland, but I encouraged him to go study under the great Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein in Chevron.

“He always davened with great kavanah, learned mussar, and had a level of yiras Shamayim that was deep and not superficial. On Shabbos he would refrain from passing by neighborhoods where the stores were open. And his diligence was boundless. During vacation when the other students would return home, Tzvi used to study from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. And he had no tolerance for the materialistic culture of America. A week before his death he wrote to a friend, “I believe that a person has to do what’s right in G-d’s eyes, and Hashem will look out for him.”

Zev Berman was living the American dream. Born in Philadelphia in 1906, he received an early Jewish education at Mishkan Yisrael, the local afternoon Talmud Torah. Tall and built, “Billy” was a dominant athlete, excelling at baseball, basketball, and swimming. At the age of 15, he joined RIETS where his oratory skills turned him into a folk hero after he led the yeshivah’s debate team to victory over Chicago’s HTC in a tightly contested meet. His father Shmuel, a simple clothing salesman who struggled with the costs of giving him and his brother a proper Torah education, wasn’t as impressed. When told that his son was such a talented speaker, he shrugged his shoulders and said, “What good will it do for me that my son is a speaker? I’d rather that he master a seder of Gemara!” And so he did.

Though he was offered a position in the Kochav Yisrael shul in Teaneck, he turned it down and instead traveled to Chevron where he’d learn with incredible hasmadah. Held in high esteem in Chevron, the roshei yeshivah regarded him as a role model, pointing to him and commenting, “We need more students like him from America.”

Yaakov Wexler’s short life — and horrific death — was a lesson in emunah. During the 1920s, Rav Yaakov Volk visited Chicago on behalf of the fledgling yishuv, and Mr. Yerachmiel Wexler — a wealthy member of the Chicago Jewish community — heard him speak. Impressed, he conversed with Rav Volk after Shabbos and they remained in contact, Rav Volk continuing to inspire him about Eretz Yisrael.

In March 1928, the Wexlers traveled to the Holy Land. Mr. Wexler traversed the land making numerous investments, including the purchase of 300 dunam of land outside of Rishon LeZion. The Wexlers visited the town of Chevron and the Knesses Yisrael-Slabodka yeshivah, where Yaakov Wexler, then just 16 and a student at HTC, became entranced with the yeshivah and begged his parents to allow him to stay. A number of the American bochurim assured Mr. Wexler that they would keep an eye on his son, and Mr. Wexler reluctantly agreed.

Yaakov was thrilled in his new environment. In order to catch up to his fellow students, he hired his host, Rav Efraim Sokolover, to tutor him for one seder each day. After four months in yeshivah, he received a letter from his aunt inquiring about his feelings for his new situation.

He answered, “Your question depends on how you define life. If a life of pleasure and luxury is what constitutes life, then I am missing out on this here. However, according to my definition of life, my life here is happy and content.”

On that fateful August day, Yaakov hid with many others in the home of Chevron community leader, Eliezer Don Slonim. Eventually the door was broken down by the mob and death seemed imminent. Yaakov started weeping and fell on the neck of Rav Sokolover, uttering his final words, which were roughly: “If I’m going to die, I’m happy it will have been after having joined a group of bnei Torah. I thank you from the bottom of my heart, for educating me in the way of Torah and mitzvos.” The murderer’s axe came down on his head and he fell.

Rav Volk was beside himself with grief and felt responsible for the tragic outcome. While he continued to travel to America, he removed Chicago from his itinerary in order to avoid encountering the Wexlers. One day he entered a shul in New York and walked straight into Yerachmiel Wexler. The encounter was now unavoidable and he stood silently with his eyes cast downward. Mr. Wexler greeted him with a smile. “Rabbi Volk, we miss your wonderful talks in Chicago. When will you be joining us again?”

He began to stammer as emotion got hold of him. With tears in his eyes he replied, “I’m so sorry, Mr. Wexler. I feel responsible for your son going to Chevron and have been avoiding you as a result.”

“You are wrong for feeling guilty,” responded Mr. Wexler. “Just the opposite. I owe you much thanks. There was a heavenly decree that my son live to the age of 17. He could have died in New York in a car accident or in Chicago from illness. As a result of your efforts, he came to Eretz Yisrael and died learning Torah in Chevron. He died because he was a Jew and there can be no nobler death than that.”

End of An Era

Following the massacre and subsequent evacuation of the Jewish community in Chevron, the yeshivah resettled in Jerusalem and began to heal, rebuilding with a roster of local talmidim. Many of the American students returned home to accept rabbinic positions, while others would depart for yeshivos in Europe. While some would rejoin the Chevron-Slabodka yeshivah in the Geula neighborhood and eventually in its current home in Givat Mordechai, it never quite attracted as large an American contingent again as it had in the early days in Chevron.

The yeshivah’s financial support, however, continued to be America-centric, with Rav Moshe Mordechai’s sons-in-law, Rav Yechezkel Sarna and Rav Moshe Chevroni, regularly traveling to the US to raise funds. Rav Yosef Chevroni, current Chevron rosh yeshivah and a great-grandson of Rav Moshe Mordechai, related to me a powerful story — a telling postscript to that era.

Like with so many others, Harry Schiff’s real estate empire was wiped out by the 1929 market crash and ensuing Depression. In 1931, Rav Yechezkel Sarna visited New York and made an appointment to see Mr. Schiff, who was by then a shell of his former self and woebegone by illness brought upon by his dramatic fall from grace. Rav Yechezkel quickly cabled Rav Moshe Mordechai to advise him of Mr. Schiff’s lamentable plight. Rav Moshe Mordechai replied that because the yeshivah essentially owed its existence to Mr. Schiff, he was prepared to borrow significant sums against the yeshivah’s new building in Jerusalem, which they’d just received from the governing body, to help him restart his business endeavors.

When Mr. Schiff heard the suggestion, tears streamed down his cheeks. “You don’t understand,” he said. “I once stood at the helm of a massive real estate empire and now it’s all lost. The only thing I have left to show is the money I gave to the yeshivah and now you’re trying to take that away from me as well? Never!”

Special thanks to Dr. Shnayer Leiman, Rabbi Pesach Wachsman, and Yehuda Zirkind for their assistance.

UNFATHOMABLE

A Liverpool native, Rabbi Lazarus (Yehuda Leib) Axelrod studied at Knesses Yisrael-Chevron beginning in 1926, receiving semichah from both Rav Moshe Mordchai Epstein and Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer. In August of 1929, he bade farewell to the yeshivah and boarded a ship bound for America, where a rabbinic position awaited him. In a 1932 article in the Southern Israelite, he shared his recollections:

Three years ago, a happy youth, ordained for the rabbinate after three years of grinding study, bade farewell to his fellow students in Hebron, Palestine. He kissed his colleagues, wept with them, and finally drove off en-route for the United States. His eyes were dim and red, his heart heavy and he turned in his seat to take one last look at those loyal friends of his devoted princes of law. There they stood, two hundred strong, waving to him from the dusty highway. He can see them even now: Dave, Billy, Jackie and the rest. Can I ever forget them?

Two weeks later I set foot on American soul. An hour later, and the sun had ceased to shine on the New York streets. I had suddenly lost all interest in my surroundings. On the full page of the newspaper a full-sized photograph stared at me wildly. Beneath the pictures I read the inscription— “William Berman, Philadelphia youth among the slain at Hebron.”

The words seared my brain. Everything swam before me. I clutched at a passerby for support. As in a dream, I read further: Dave Sheinberg, Memphis; Benjamin Hurwitz, Brooklyn; Aaron David Epstein, Chicago; Jackie Wexler…

God!!! Jackie, Billy, Dave and the rest of “our gang” killed by filthy Arabs. I stood there on Broadway. The “elevated” rushed along roaring, like a demon, taxis flitted through the street like so many flies, men and women pushed and shoved me indifferently as they hastened on their way, the banana peddler on the corner called attention incessantly to his pushcart. I was oblivious to all of this. Mechanically, as in a trance, I made my way to my room. Ill for several days, I lay on my couch, gazing helplessly through my windows at the colossal skyscrapers of this metropolis. Magnificent structures, vast and towering, they left me cold. My thoughts turned to a small modest stone building in Hebron, whose walls even now were moist with the blood of my colleagues. Yeshivah walls — koslei beis hamedrash.

THE NINTH VICTIM

In 1953, the American survivors of the massacre gathered together in Cleveland where they relived the tragedy anew. Ohio native Sol Goodman, who on that fateful day in 1929 was hidden together with his brother Manny by a friendly Arab grocer under a pile of manure, had his kidney punctured by the probing knives of the raging mob. Bleeding profusely, he remained hidden until given the all-clear some hours later. He suffered for over two decades from the wounds he sustained before succumbing and facing an untimely death.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 829)

Oops! We could not locate your form.

Comments (3)