Opposite the Glass

| May 25, 2021Justice Gavriel Bach relives his prosecution of Adolf Eichmann

It was May of 1960, and Prime Minister David Ben Gurion has just made the shocking announcement that Nazi arch-criminal Adolf Eichmann had been captured by the Mossad and brought to Israel for trial. Days later, a young jurist named Gavriel Bach was given an assignment that would forever change his life.

Bach was a lawyer in the State Prosecutor’s office when the chief architect of Adolf Hitler’s “Final Solution” to exterminate Europe’s Jews was seized by Israeli secret agents in Argentina. And a year later — 60 years ago this month — as the Eichmann trial got underway and Israelis finally confronted the enormity of the atrocities buried deep in survivors’ souls for over 15 years, it was Gavriel Bach who took center stage.

The 94-year-old retired Supreme Court justice remembers the phone call from Israeli Justice Minister Pinchas Rosen soon after Eichmann’s capture. Rosen asked that the German-born Bach serve as deputy prosecutor in the case under attorney general Gideon Hausner, but had another request as well — that he be in charge of the entire pre-trial investigation. And there was something else too: For the coming months, Bach would serve as the liaison between the arch-murderer and the outside.

Around the world, millions waited for the trial with bated breath. The staggering agony of the Holocaust, which survivors until then were reluctant to speak about, especially in Israel where “non-heroic” survivors (those who weren’t partisans or didn’t participate in resistance operations) were treated with scorn and derision — suddenly exploded with unfathomable pain. The long, tortuous trial period during the summer of 1961 was perhaps the first psychological attempt for Israeli society, as a collective, to process the horror.

Especially the Children

Bach, who agreed to take the mission, was a natural choice. He was fluent in German and had already proven himself as a top-notch jurist in several high-profile cases over the previous decade, including the famous Kastner trial of the 1950s, in which government employee and former Hungarian community leader Rudolf Kastner was accused of being a Nazi collaborator and judged for having “sold his soul to the devil.”

And so, Bach packed his bags, parted from his wife, Ruth, and two children — two-and-a half-year-old daughter Orly and one-year-old son Yonatan — and spent the next nine months as the legal advisor to Bureau 06 of the Israel Police, which was set up to assemble the evidence against Eichmann. They worked out of Al Jalameh Prison outside Haifa, which had been cleared of its occupants, re-fenced, and provided with tight security, and began to research and amass documents from all over the world in preparation for the trial.

It wasn’t easy. The horrific material Bach encountered gave him no peace for years to come, and the isolation from his family was difficult. He could return home for weekends, but even then, his heart and mind were still filled with the scenes and documents he had viewed throughout the week.

And he’ll never forget his first encounter with Eichmann himself. As part of his duties, Bach liaised between Eichmann and the outside world. If the prisoner had a request, he was to inform Bach.

“That morning,” Bach remembers, “I was in my office reading an autobiography written by one of the most heinous murders, Rudolf Franz Höss, the commander of Auschwitz. Höss was apprehended after the war, put on trial in Poland, and executed by hanging in 1947 inside the Auschwitz camp. He spent his final days writing memoirs.

“So here I was, reading a passage where Höss described killing about a thousand Jewish children a day, but admitted that even for him, sometimes it was too much. ‘Sometimes,’ he described, ‘I felt weak-kneed.’ But there was one thing that made him rally: ‘After I spoke to Obersturmbannführer Eichmann, he explained to me that it was especially important to kill the children. It makes no sense to kill only adults and then to leave alive a generation of avengers, Eichmann explained.’

“As I was trying to digest what I had just read,” Justice Bach recalls, “I suddenly received a message: Eichmann wants to see you.

“When I heard his footsteps in the corridor as he was led to my office, for a moment I saw myself as a little child standing with my family on the platform at Auschwitz.”

He remembers how Eichmann, henchman that he was, always remained a German gentleman. He always tried to be polite, and every time he’d encounter Bach, he would stand at attention.

Time to Run

Even now, in his nineties, Gavriel Bach is courteous and professional as ever, making sure to greet us wearing a tailored suit and tie. He excuses himself for a moment, and then returns with an ancient valise in hand. “This suitcase is really the backstory,” he says of the prop he’s pulled out.

Bach was born in the city of Halberstadt, in central Germany, in 1927. A year after his birth, the family moved to Berlin, where his father, Victor Bach, was a manager of a copper and brass factory owned by the Hirsch family, who were mitzvah observant and members of Agudas Yisrael.

When Gavriel was born, his father gave him two names, Gert and Gavriel. Says Bach, “My father, who was an ardent Zionist, gave a speech at the bris, and said, ‘You, my son, will choose whether to be Gavriel in Eretz Yisrael, or Gert in Germany.”

As happened to most of Germany’s Jews, they were not the ones who chose. The Nazis made the choice for them. His childhood years were turning points in history — the red Nazi flags with the black swastikas waving from every window, the hobnailed boots and the raucous national songs.

It was 1938, just two weeks before Kristallnacht, and Victor Bach’s senses were on high alert. He realized that they had to flee, and so he sold the house, gave every child his own valise, and planned their escape to Amsterdam, Holland.

But on the way, the family was stopped, and their immigration papers and passports were confiscated. Victor was not allowed to leave the country in wartime, the officials claimed, because he had extensive knowledge about the German metalworks industry.

While the Bach family was left in an uncertain state, the global political scene was seeing a remarkable march of folly. The Bachs were able to take advantage of the small window of calm after British Prime Minister Chamberlain’s ill-fated and short-lived appeasement treaty to make another escape attempt. They had received their passports back, boarded a train, and got as far as the Dutch border, when several SS officers entered their train car and announced: “Bach family, off the train with your valises!”

They searched their possessions, and as the train was about to leave without them, a miracle happened and one of the officers shouted for them to get back on the train. The entire family grabbed their suitcases and ran to the train, which was already beginning to pull out of the station. One 11-year-old-boy lagged behind, running desperately with his cumbersome valise. Then a Nazi officer appeared behind him and gave him such a strong kick that he simply flew with his valise into the train. “That’s how I was thrown out of Germany,” says Bach, “with this suitcase and a kick.”

Amsterdam, with its canals, its picturesque houses and its bike riders, might have been a pleasant refuge, but soon the news came of the civil war that broke out in Spain, of the Italians invading Albania and of the Nazis flooding Lithuania and invading Poland. In no time, all of Europe was burning. The Bach family realized they had to flee from Holland. While they were considering different means of escape, Hitler meanwhile delayed the invasion of Holland seven times, each time for a different reason.

A month before the German invasion of Holland, the Bachs boarded the Patria to Eretz Yisrael. It was the last time the ship sailed — on its next journey, it was sunk by a bomb that took the lives of 250 people.

As they were setting sail for a more Jewish future, Gavriel celebrated his bar mitzvah. He had an aliyah to the Torah on the ship, and there at sea, he left behind his secular name, Gert, and became Gavriel. Later they realized just how lucky they were to get out in time. “A few years after the war,” Bach relates, “I discovered that of the 12 Jewish children in my class in Amsterdam, I was the only survivor.”

Once in Eretz Yisrael, young Gavriel’s language and the German mannerisms were replaced by the more prickly Sabra way of life. Gavriel was just 16 when he joined the Haganah in 1943 while attending high school at the Hebrew University Secondary School, graduating in 1945. After a year of university studies at the Hebrew University, he received a scholarship to study law at University College in London. Upon his return, he did his IDF service in the military’s legal corps, and in his reserve duty, he served as a judge on the Military Court of Appeals, reaching the rank of colonel. He occasionally noticed a reserve officer sitting in on his courtroom sessions, who introduced himself as Colin Gilon, the deputy state prosecutor — he wanted to offer Gavriel a job. And that’s how, in 1953, Gavriel Bach began working in the State Attorney’s Office.

Changing the Narrative

But of all the cases he’d worked on during the next seven years, nothing compared to the prep for the Eichmann trial. His first job was to lead the team at Bureau 06 in preparing a detailed indictment. Mountains of materials, testimonies, and documents from all over the world were gathered, painting a shocking picture of Eichmann’s diabolical dedication to the mission he was tasked with.

“The investigation was conducted like a military operation,” he relates. “There was a separate person in charge of each country. One investigated the Holocaust in Hungary, a second in Poland, the third in the Baltic States. There was also a central officer for each subject: the legal issues, the organization of the murders, the looting. Everything was closely researched and documented.”

More than just a trial of Adolf Eichmann the individual, the trial also finally gave rise to an open discussion about the Holocaust and the hundreds of thousands of survivors in the State of Israel. Until then, survivors were embarrassed to share what they had experienced, especially for fear that they would not be believed, and even more humiliating, that they’d be mocked for “going like sheep to the slaughter.” The Eichmann trial would help change the narrative and excoriate the shame.

And it began while Bach’s team was still gathering information in Bureau 06. “At one point,” Bach remembers, “we received a document with a detailed list of Jews who arrived in Auschwitz in 1942–1943. There were dates but instead of names, there were just the numbers that had been burned into the inmates’ arms, which made the evidence-gathering process problematic from a legal point of view. But then I suggested, ‘Maybe we can work in the reverse. Let’s try and find the people who have these numbers on their arms, we’ll check the dates when they came to Auschwitz, and then we can confirm the accuracy of the document.’

“Of course, the problem would be to actually find any of these people, if they actually survived. But even before I finished speaking, one of the officers stood up. His name was Micky Gilad. He was tall and strapping, a real Israeli Sabra. None of us knew anything about his past, or that his name had been Goldman. Instead of speaking, he rolled up his sleeve and showed us his number. ‘I came to Auschwitz in September 1943,’ he said. We all fell silent — none of us knew what to say.”

Then, for the first time, this tough-as-nails police officer began to talk. Later, during the actual trial, witness Dr. Yosef Bushminski would identify Micky Goldman and tell everyone his story. “Even before Micky came to Auschwitz,” Dr. Bushminski said on the stand, “he was caught by an SS officer, who beat him with 80 blows, when 50 are enough to kill a person. When he finished, and miraculously the boy was still alive, the Nazi shrieked satanically: ‘Let’s see if you can get up and walk.’ With herculean strength, the nearly dead youngster stood up and ran away.”

When Micky spoke about the 80 blows, he also shed light on what he called the “eighty-first blow” (which became the title of the book he later wrote). “When I came to Eretz Yisrael and began to relate what I had been though, and everyone snickered in disbelief, I felt like it was an even more painful blow than all of those,” he said. From that point on, until Eichmann’s capture and trial, he didn’t tell anyone what he had been through. Tens of thousands of survivors did the same.

Bach and his team realized from the start that in order to get a conviction, they couldn’t rely solely on documents — they’d need testimonies from live witnesses. And while the decision to put witnesses on the stand stemmed from legal considerations, it served a critical role in the way the world has come to understand and remember the Nazi killing machine. Bach was in charge of coordinating testimonies from France, Belgium, Holland, the Scandinavian nations, the Balkans, Italy, and especially from Hungary, with a representative from every concentration camp and ghetto.

In the end, 110 survivors testified on the stand, sharing their personal horrors of the ghettos and the slave labor and extermination camps under Hitler’s regime, and exposing for the first time in such a public forum the true scope of the unfathomable horrors of the Holocaust.

No Fear

Bach remembers his first encounter with the defendant. Eichmann stood in front of him, a typical-looking middle-aged man with nondescript glasses, and politely asked for advice about “which lawyer he should appoint for himself.” (In the end, he was represented by German attorney Robert Servatius, who had defended other Nazi war criminals as well.)

“He didn’t show any signs of fear or make attempts at flattery,” says Bach. “He was calm and collected, although he was very aware that he was a prisoner. At one point when I stood up, he too rose from his chair and stood in silence. He was a very distinct product of a rigid and hierarchal society, and quickly internalized his status as a prisoner. He made sure to ask permission even if he wanted to leave over one of the three slices of bread he was served.”

According to Bach, Eichmann quickly got used to the schedules and the demands of his prison term and trial, and stood in silence in front of anyone whom he saw as a figure of power or authority.

But, says Bach, behind the benign-looking man was a monster. “The horrific documents made my hair stand on end over and over again,” he says. “Eichmann was the final authority in everything connected to the mass murders.” And everything was scrupulously documented. “He was guided by one principle: Not to leave one Jew alive.”

In the evenings, Bach would sit together with Avner Lass, an officer who spoke German and who was charged with interrogating Eichmann. Together, as the two would listen to the recordings of the interrogations, they began to realize the line of defense Eichmann was preparing for himself. “I was just carrying out orders,” he would say. “I was in Auschwitz, but I didn’t peek inside. I cannot stand the sight of blood.”

What became increasingly clear was that this was not the trial of one person; it was an opportunity to finally and unequivocally lift the veil off what the Nazis perpetrated during those years.

When the preparations were complete, Gavriel Bach met Eichmann again, and presented him with the indictment. Eichmann was asked to sign it. He complied, of course, and signed, adding in German, “With reservations, as I do not understand Hebrew.”

The Red Coat

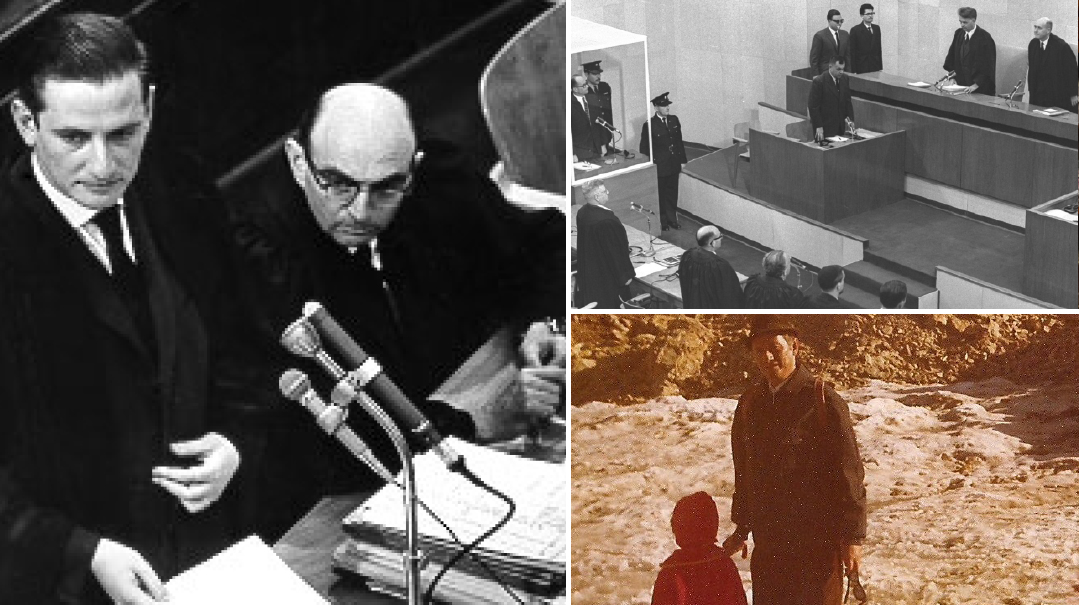

The famous photos of the trial that opened in Jerusalem’s Beit Ha’am auditorium show the prosecution team, including a young Gavriel Bach. They all understood the magnitude of the moment. “We knew that this was a trial for history,” Bach says.

The Eichmann trial was a game-changer in many respects. The first to be televised, the trial would allow millions around the world access to the courtroom. And the testimonies would finally give young Israelis, who could not understand why the Jews of Europe seemed not to defend themselves, a window into the devious tactics of the Nazi killing machine.

When Eichmann tried to claim that he was only a “cog in the destruction machine,” the Hungarian deportations were used as a rebuttal. Eichmann himself traveled to Hungary to oversee the annihilation of the Jews there. In a newspaper interview at the time, he stated, “Even if Germany will lose, I won my personal war — to destroy as many Jews as possible.”

While Bach will never forget that moment when the court bailiff announced “The court will come to order!” and Eichmann, in the glass cubicle, stood on his feet, there were also some difficult personal moments. One of them was when a witness, Dr. Martin Foldi, a Hungarian Jew from Auschwitz, took the stand. Foldi’s testimony was spontaneous — Bach hadn’t heard his story at any pre-trial interview. Then Foldi began to describe a scene that has become a documentary symbol of Auschwitz.

He described how he had arrived with his family at the famous platform, how they were disgorged from the cattle cars and ordered to descend and to leave all their belongings behind. Men and children over age 14 were sent to the right. Women and small children — to the left.

“My wife and daughter began to walk to the left, while I stood with my 12-year-old son,” Foldi described. “The SS man asked how old the boy was, and when he heard that he was not yet 14, he said, ‘Run to your mother.’ And I continued to the right. I looked into the distance, trying to see my family, but it was hard to discern them. But my two-year-old daughter was wearing a red coat. That was my sign. I gazed at that red spot, which grew smaller and smaller, and that’s how my family disappeared from my life.”

There was utter silence in the courtroom. The television cameras were rolling, focused on prosecutor Bach’s face. The judges signaled to him to continue to cross-examine the witness, but he stood frozen, rooted to his place.

“Hearing this testimony, seeing it in my mind’s eye as the red dress moved toward the gas chamber, I was unable to utter a word. All I could do was shuffle around some papers for a few minutes before I regained my composure,” he later explained. “Because just two weeks earlier, I had purchased a red coat for my two-year-old, Orly. When the witness described the separation from his daughter, I felt myself choking up.”

(The red coat became a symbol of sorts. In Steven Spielberg’s 1994 Oscar award-winning movie, Schindler’s List, one of the most moving images is the little girl in the red coat wandering alone on the way to the gas chambers amid the black-and-white horror and chaos, her lifeless body eventually seen on a pile of corpses.)

“To this day,” relates his daughter, a psychologist, “my father can be walking in the street, or even be sitting in a restaurant, and suddenly, his heart starts to pound wildly, without knowing why. And then we notice a boy or girl with a red coat passing by. This coat became a symbol of the trial for him.”

There is another moment from the trial that accompanies him.

A few months after the trial opened, a special witness took the stand: Nachum Hoch, who emerged alive from the gas chambers. He related that he was among a thousand children who had been pushed into the chamber. Whoever tried to object, to plead for his life, was shot on the spot. The doors were slammed closed and locked. There was absolute darkness. Another moment, and a thousand children would rise in a storm to the Heavens.

“A few children began to scream Shema Yisrael,” Hoch related, “and then, one older boy decided to soothe them. He called in Yiddish, ‘Zingst kinderlach! Sing!’ And a thousand Jewish children began to sing their last song on this earth.”

And then the doors opened. Apparently, trucks with a huge shipment of potatoes had arrived. The Nazis needed hands to work. The 50 children who stood closest to the door were saved. Nachum Hoch was the only one of those 50 who later survived to tell the story.

He finished his testimony, and there wasn’t a dry eye in the court. From the photos, it looks like even the angel of death himself was hanging his head. It was impossible to continue. A recess was called. Bach went into his office, and was surprised to see Eichmann’s lawyer enter the room. His eyes were also moist. Even he could not remain indifferent in the face of the heroism of the Jewish children.

Curtain at Midnight

While the Eichmann trial was perhaps Gavriel Bach’s most famous stage, in subsequent years he had become one of Israel’s most venerated jurists. In 1969, he was appointed State Attorney. In 1982 he was appointed as a judge of the Supreme Court of Israel, from which he retired in 1997. He was subsequently appointed as the chairman of several senior government committees and fact-finding commissions, and has represented Israel at many international conferences.

Still, he says, “While 60 years have passed, not a day goes by that I don’t think about some particular item, or some particular piece of evidence, or some particular moment from the Eichmann trial.”

While some people, including famous German-born American political theorist Hannah Arendt, called the proceedings a predetermined show trial and an opportunity for Jews to have their revenge on the Germans, as opposed to an objective execution of justice, Bach — who is still too well-bred and polite to attack — says simply, “I’m sorry for everyone who believes those words. The conviction was totally evidence-based — and we didn’t even know until the last moment what the verdict would be.”

Eichmann, as we know, was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging on December 15, 1961. After his appeal was denied, he asked Israeli President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi for clemency.

“All my life, I objected to the death penalty — except in this case,” Bach says.

“When they announced on May 31, 1962, that President Yitzchak Ben Tzvi had refused to pardon Eichmann,” Bach’s daughter Orly relates, “my father paled. It was eleven o’clock at night. Earlier, my father had advised that the moment the president refused to pardon him, they should carry out the sentence within an hour, in order to preclude neo-Nazi elements around the world from taking hostages and the like. My father knew that actually, in another hour, the ashes would already be scattered.”

And that’s what happened. Eichmann was hanged at midnight, his body incinerated in a specially-built oven, and his ashes scattered over the Mediterranean. “The police invited me to be present,” says Bach, “but I didn’t want to be there. I’d already done my job.”

—Rachel Ginsberg contributed to this report

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 862)

Oops! We could not locate your form.