Window to the Soul

Celia Tawil de Cattan’s art uses myriad mediums — all threaded with dreams

"A work of art which did not begin in emotion is not art.” —Paul Cezzane

I meet Celia Tawil de Cattan at a small, COVID-style engagement celebration in Jerusalem.

“You have to see the windows she made,” someone says.

And Celia starts to get teary eyed. “It was from G-d, a huge project…” She chokes up, brimming over with emotion at the mere mention of her work. If that’s not art, I don’t know what is.

I also know there’s a story there, a connection stronger than words.

“I’ll take you to see,” Celia says, smiling through her tears.

Autodidact Artist

First, I am invited to Celia’s studio which, due to COVID, is now in her house. Her home is white, glass, modernistic, with windows that spill late afternoon sun into the rooms. There are touches of “old world” too. A fireplace centerpieces the room. Hints of Mexico City, her birthplace and home for decades, are in the flashes of warm color in the cushions, rugs, and throws. Art — in every form — abounds.

“I’m an autodidact,” Celia says as she shows me around. “Whatever I know, I taught myself. I’ve had no formal art training, but I’m learning all my life. From as young as 12 years old, I’ve been experimenting with different media. I learned day by day, through trial and error.”

This grandmother and great-grandmother has used it all — canvas, wood, ceramic, aluminum, copper, zinc, glass. “I use the medium that reflects what I want to say,” says Celia, who primarily paints and sculpts.

She shows me a ceramic circle of people, generic figures holding hands, embracing, and two larger figures encompassed by the rest. “This is one of the first pieces I did after making aliyah seven years ago,” says Celia. “I missed my own family, the clear roles my husband and I had within it as heads of our family. But all of the Jewish people are my family, and that’s what I tried to represent in this sculpture.”

Reminiscing, Celia adds, “When I moved to Israel, walked the streets, I felt different, lighter, free. I felt a sense of calm and peace that we didn’t have in Mexico.”

She explains that while the Jewish community in Mexico City was basically safe, there was wariness and cautiousness. The Jews were eager to support the government, to build connections, to buy their safety. Celia remembers her uncles having VIP visitors over, hushed conversations, exchanges of money. “Mexico wasn’t — isn’t — the straightest place,” she says.

Celia then takes me into her studio, which is dominated by two easels. Both have canvases with images of hands on them, as Celia was recently commissioned to paint a set of five hand-themed pictures for a long hallway. So far, she’s completed a child’s hand gripping an adult’s and is currently working on a tower of fists. “The other images will come to me… in time,” says Celia with a quiet confidence.

The Mexico City that Celia grew up in was a bastion of art and culture. In her youth, Celia developed an interest in museums and galleries, and, encouraged by her parents, would spend hours exploring them, trying to learn from every piece. Early on, she was exposed to Rembrandt and Leonardo da Vinci — two artists that inspire her until today.

But her primary inspiration is Marc Chagall, an early Modernist, who had made his mark on Mexico — and it on him — back in the ‘40s when he painted the set design for the major ballet performance Aleko that premiered in Mexico City in 1942.

“Oh, Chagall,” Celia says almost affectionately. “There’s so much in his paintings. When you paint, everything goes in, whether you’re conscious of it or not. Your state of mind, of heart. Your stage. When someone likes a painting, it’s because they feel the artist’s state, his sentiments; they relate to it. That’s the communication an artist can have. I feel that when I look at Chagall’s work. And his use of color!”

Celia wasn’t satisfied with just looking at art, though; she wanted to create her own. And her father, who was enthusiastic about her creativity, wanted to help. He had confidence in her abilities and, because of his line of work in advertising, he was able to procure materials —canvases, acrylics, whatever she needed — so she could keep creating.

“I used everything at my disposal to create art,” Celia says. “That’s what my father encouraged me to do.” By the age of 17, she’d developed her natural talent to the extent that she was able to produce a masterpiece for her future in-laws — a painting of a man blowing a shofar — which she presented to them on Rosh Hashanah shortly after she got engaged.

Soldiers for Hashem

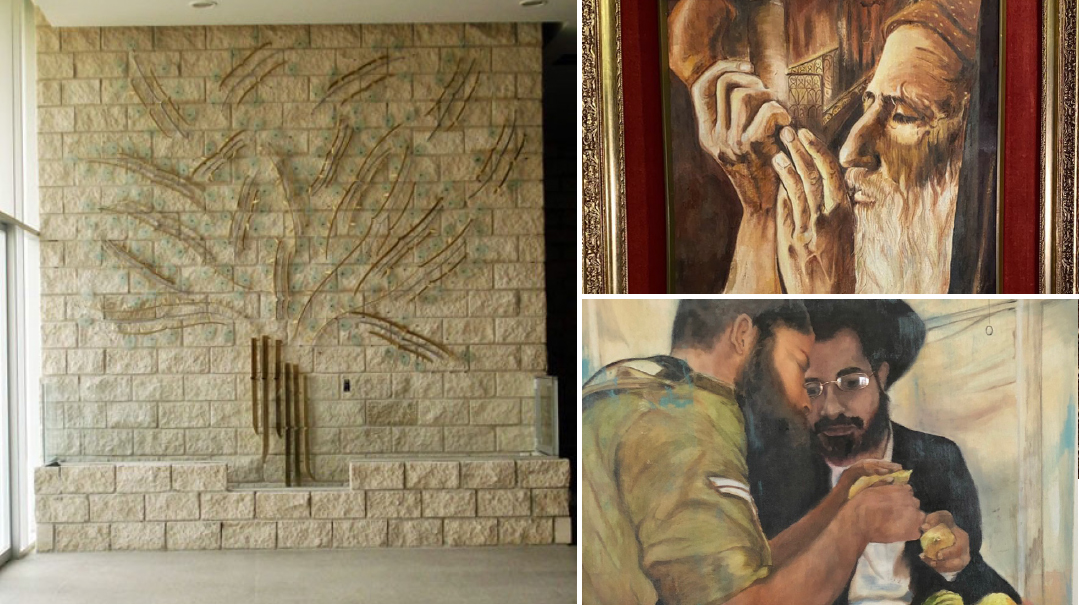

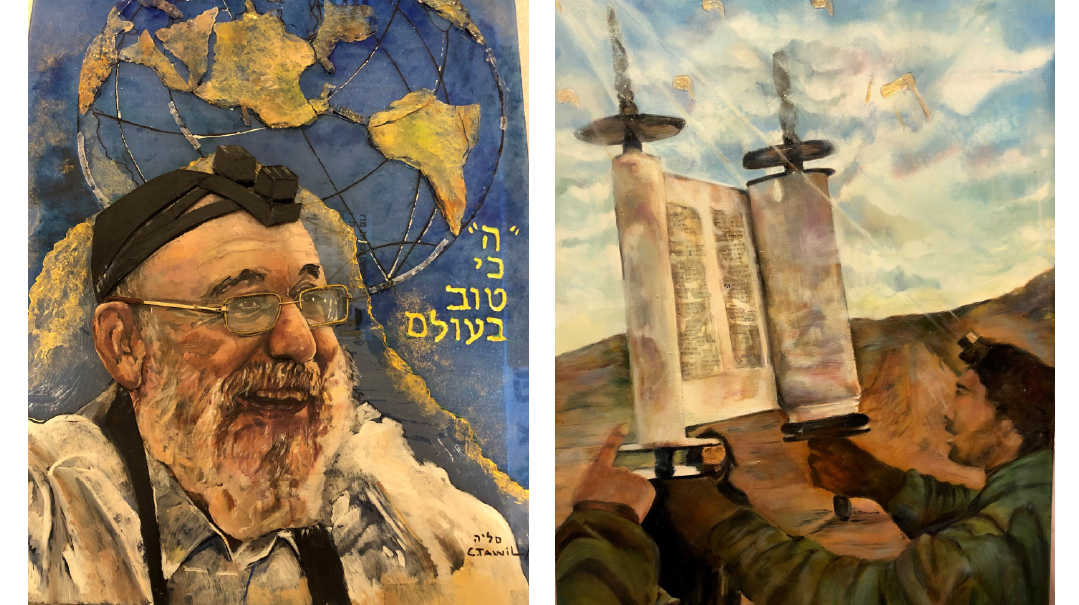

We leave Celia’s studio and examine the paintings in her living room, most of which have a Jewish theme. “I was always drawn to Jewish themes. And not just Judaica; how Jewishness and life work together,” says Celia.

She has a fascination with Israeli soldiers in particular. “We’re all soldiers,” Celia says. “As a Jew, you’re a soldier for G-d.”

She once saw an Israeli soldier on a street holding a lamb. “A real tiny lamb,” she tells me. “I just had to paint that.

“Another time we were driving to Chevron and a couple of soldiers were stationed at the entrance and there was a box of cauliflower near them. All that green. The contrast of the greens. The ordinariness of the box of cauliflower next to these young people in green, in a tempest place like Chevron…”

She’s not involved in the politics of it; to her, we’re all Jews, all soldiers, some in green and some in hats. Messages of peace and unity fill her work.

One year, before Succos, she visited the shuk with her husband to select an esrog, and she saw a soldier and a rabbi poring over the esrogim. “The two of them together, I had to paint that, too,” says Celia. The directions in the paintings (in Spanish) symbolize the four corners of the world, the directions in which we shake and point the species. The picture is an oil painting but the rabbi’s glasses are real. Celia created them from metal and glass and stuck them onto the painting. A creation of mixed media.

“This is something else from aluminum and glass,” she says, showing me a picture of a huge piece of artwork she made for her grandson’s school back in Mexico. She took the concept from the school’s emblem — a “tree of life” — and formed an aluminum tree with leaves of glass, where the names of donors were engraved.

Though Celia has been in Israel for almost ten years now, a piece of her heart is still back in Mexico. Not just her heart, but also her deeds — she was a pillar of her community. Thirty, forty years ago, Mexico City was a spiritual desert. Celia helped to bring taharas hamishpachah there, to make it the done thing.

“I worked with the committee that built the mikvaos,” Celia says. “Since I also trained in interior design and know architecture, I was able to help with the planning and the design. We made it beautiful, like it should be. I’m into congruence: a beautiful mitzvah should be performed in a beautiful setting.”

She also volunteered at the mikveh for 30 years. Over time, people started to keep taharas hamishpachah and slowly to take on other mitzvos as well.

Back home, Celia was well known. She was commissioned to do artwork for synagogues, private jobs for people’s homes. But she yearned to create something more, something beyond the borders of Mexico: “Each time I visited Israel, I’d open the windows and look out at the rooftops and sky and people, and think that I’d love to create something in Eretz Yisrael, for Eretz Yisrael.”

And then after more than half a century of living in Mexico, the Cattans made Aliyah.

Rav Reueven Sharabani, a noted mekubal, was their rabbi, and he guided them in Israel. It so happened that his daughter was the principal of an art institute. Celia got a studio in the institute and started to make ceramics.

“The other artists, they would talk to each other in Hebrew, and there I was, trying to learn a new language at an advanced age.”

In the grand synagogue in Mexico, Celia tells me, people pray in Spanish. “Still, I always had this inexplicable love for the otiot. I put them everywhere, in my paintings, in ceramics.” She points to a set of dishes with aleph-bet floating about in the design.

Making aliyah wasn’t easy; people didn’t know Celia and her skills and talents. She dearly wanted to create something special for the Holy Land, but didn’t know how to go about it. So Hashem sent a project directly to her.

Work of the Soul

The Cattans had an old connection with Succat David, a yeshivah in Yerushalayim founded by a fellow Mexican, Rav Menachem Basri. When the yeshivah purchased a new building, they contacted Celia and asked her to do some work on the windows. They didn’t know exactly what they wanted; they were thinking about some Judaica designs in stained glass. Celia sketched some ideas and created a small sample for them that she thought she’d recreate for a big middle window in the beit knesset.

A few weeks later, they called to say they were sorry but they wouldn’t be able to go ahead with the custom-designed windows after all — they’d been relying on some money that didn’t come through.

It hit Celia harder than she expected. She realized how badly she wanted to create something special for a holy place like a yeshivah or shul. “So I spoke to G-d. I told Him, ‘It’s okay, I know you have another project for me.’”

She got on with her own artwork, got busy with her life. Half a year later, another call came from Succat David.

“Can you come over to see the building site?”

“What for? I thought you didn’t want the windows done in the end.”

“Just come,” they said.

Two members of the committee were at the site when Celia arrived.

“It was this huge skeleton of a building, immense and shadowed. They took me down to a vast room, which was going to be the beit knesset. One of the men indicated the hollow spaces in the wall where dusk was pouring in. ‘You see? That’s where the windows are going to be. That’s what we want you to do. All of it. One of our donors saw the building plans and wants to sponsor the work of the windows.’

“I was looking at these huge spaces, in this big auditorium-style room. They were enormous, four meters high. I’d never done anything like it before. I thought of what I’d said to G-d, that He’d send me another project; I knew this was it, but I was overwhelmed. I felt His gift, the privilege He was sending me, but the dark, the dust, the building work, the immensity of the project… I teared up and told G-d I’d need His help, Hand in hand.

“The men turned to me: ‘Will you do it?’ They knew nothing of what had gone on in my head. I nodded through my tears.

“The fact that this was a project completely of glass wasn’t lost on me,” Celia continues. “With glasswork, I knew it was inner work. Complete transparency. Work of the soul.”

Celia was given a month to decide what she wanted to design in those huge windows. “For two weeks, I hardly slept; I was consumed with the project,” she says. “Finally, I told them that if they wanted me to do it, they’d have to trust me. I can’t tell you what I’m going to do in advance because if I say I’m going to do a menorah and my heart tells me later to do just an olive branch… I didn’t want to commit. I wanted it to be natural, an expression of my soul; I wanted to hear G-d’s voice inside me and work with Him.”

And, somehow, they agreed.

Celia had worked with glass before and had perfected an innovative technique of cutting glass with a glass-knife, layering it, and then painting it. She’d done a special portrait of her rav, Rabbi Reuben Sharabani, on glass, using this technique. But the windows for Succat David were of a different kind of glass entirely. As a synagogue and yeshivah, it was a marked building and the windows were made of tough, reinforced glass.

“I’d never worked with that sort of thing, but G-d was with me; I was on it.”

But first she needed a studio, a space to work on the tall windows, as her own studio was too small. The school gave her a room to work in, right near the kindergarten, where little children were learning about mitzvot.

The windows were stacked against the wall, but she needed a large table. “I asked the yeshivah for one, but nothing happened. I understood that, in this country, if you need something, you get it yourself. This is completely different than in Mexico, where servants are at your beck and call.”

She found school desks and lined 12 of them up to form a four-meter work station. Outside the building, near the garbage, she stumbled upon a large roll of fabric. It was thick and durable, a perfect work surface. “It was lying there like manna from G-d,” she said. “And I knew He was showing me that He was with me. Hand in hand, like I’d asked. I still have that fabric, rolled tight in the trunk of my car. When G-d sends you manna, you don’t throw it away.”

She made a list of all the supplies she needed and set out to an art supply store in Tel Aviv. As she and her husband were nearing the town, a missile siren sounded in the air. The Cattans were terrified; they stopped the car and ducked in their places. When the siren stopped, they continued on to the store, but just as they entered the building, the siren sounded again.

“Everything flew out of my head. I couldn’t think what colors and tools I needed; I thought I was about to die,” Celia relays. “The Israeli storeowners calmly led us to an inner room — no fluster, no fuss. I breathed in, and took my cue from them. Amid uncertainty, I’d get on with my work, like these stalwart people, this stalwart place.”

The very next day, Celia started the project. “For me it was a Bereishit, and that’s where I started. With nothingness, with water, tohu vavohu. And from there a globe, a world. I was thinking of the beginnings of beginnings, how G-d created this beautiful, natural world, full of brachah. And how we can have all of that brachah if there is shalom between us.”

A dove holding an olive branch above the waters represented that peace, as did the hands on the top of the picture. “Those are the hands of the Kohanim blessing the nation, a blessing for shalom,” she explains.

“I worked organically; I didn’t have a big-picture plan. As I finished one window, the ideas for the next came. In the first, I had done something abstract, the world. I wanted to ground and root the next picture. The Jewish people are compared to a tree; we are rooted with Torah and our ancestors.”

From there came Shabbat in Jerusalem. And then Ir David, and the musical instrument of Dovid Hamelech, the psalms and a keter at the top to represent Mashiach. This is where Celia upped her ante, not only layering glass, but attaching full sculptures of glass onto the pictures.

“I had bought sheets of glass, clear glass, brown glass, but I wanted different sizes, I started to use whatever glass I could find — wine bottles, beer bottles. I’d smash them and work with the shards.

“I didn’t use gloves because when you’re working with such fine, small pieces, you need the sensitivity of your fingertips. My hands became full of scratches. Once I went to the Dead Sea and the salt healed and softened my hands. After that, I went many times to dip my hands into the healing sea.”

The next window was an image of the Kotel. “Like I said, I had this thing with otiot. The notes in the Kotel, full of otiot and heartfelt words, are close to my heart. So I put glass notes in the glass stone. I also put a man wrapped in a tallis, blowing a shofar, and a sculpture of a pair of tefillin.

“It became a depiction of The Wall and our expressions of prayer. And above it, sky, rays of light, to show the seven skies opening above us when we pray.”

A window of the Menorah followed. The light of prayer and learning rising up to heaven like flames. Celia created seforim out of glass, the Talmud and the Mishnah. She made an exact replica of a Succat David siddur, with the name of her son.

The seventh window portrayed the Shalosh Regalim. Ever the multimedia artist, Celia used shells from the beaches of Israel in the Krias Yam Suf representation of Pesach.

For the Shivat Haminim window, she created sculptures of fruit. The ninth window, the last in the enormous focal wall is, naturally, the Beit Hamikdash. “It’s an end and a hope for a beginning.”

There were an additional two windows where Celia let herself go completely abstract. “These are windows of infinity. I put the four elements in: fire, water, earth, and air, and then swirls for the infinity of G-d within our natural world of elements. It’s about bringing G-d into our world, getting carried beyond nature…”

Celia is a woman of fierce faith and deep emotion, and her passion and feeling shines from the glass.

After working on the windows for three and a half years, Celia completed them in 2018.

“When they transported the windows from the old yeshivah to the new building, I came along in the truck to direct the project,” she remembers. “As we meandered our way through the jolts and bumps of Jerusalem, I sat there trembling. From fear that something would smash and shatter, from gratitude that this was actually happening.”

She’s crying as she relives those moments for me. “To create art is like giving birth — that was my labor and delivery.”

Once Celia looked out of a window, a visitor to this land, and dreamed impossible dreams. Now these incredible windows look back at her, a fulfillment of her yearnings. “When you have a dream, and you have emunah, you can do it,” Celia says. “G-d is with you. Hand in hand.”

Celia can be contacted through Mishpacha.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 744)

Oops! We could not locate your form.