Red Letter Days

A chronicle of faith, hope, survival, and blessings against all odds: letters of hope and faith from Rav Zalman Sorotzkin's children

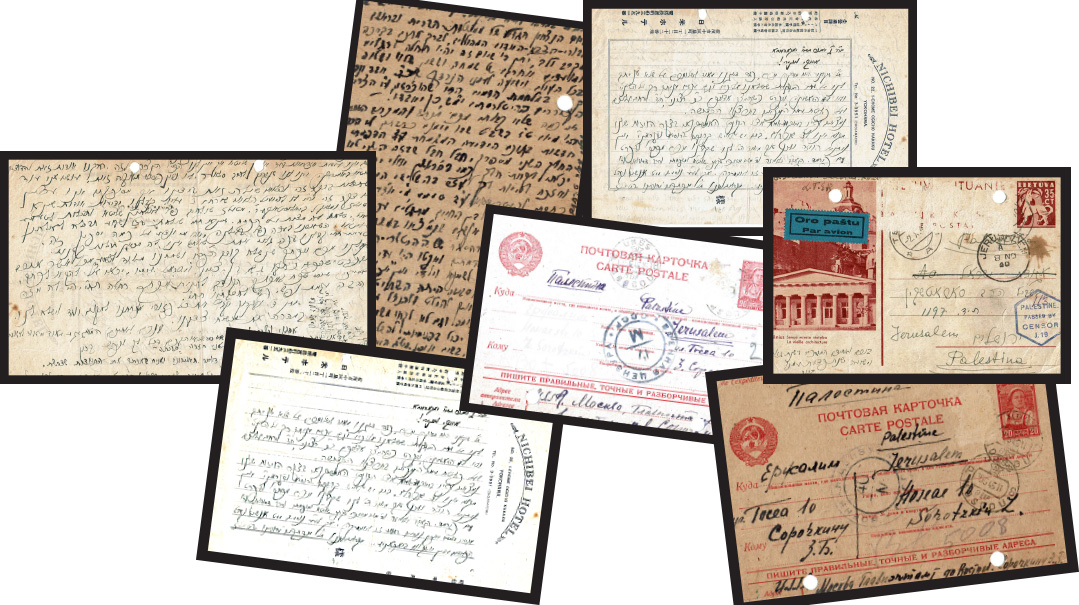

Photos: Family archives

The central train station in Vilna was eerily quiet on that chilly day toward the end of 1940, in the early days of World War II. The city, along with the rest of eastern Poland, was occupied by Soviet forces, and for the time being, the 55,000 Jews living in the city, in addition to another 15,000 Jewish refugees from German-occupied Poland, were safe. In a few months, Germany would attack Soviet forces in Eastern Europe and occupy Vilna, creating a ghetto and sealing the fate of its Jews. But, then, there was still a possibility of escape.

Waiting to board the train was Rav Zalman Sorotzkin, son-in-law of Telshe Rosh Yeshivah Rav Eliezer Gordon and the rav of the Ukranian town of Lutzk, where, as a leader of Agudas Yisrael, he became renowned as one of Eastern Europe’s outstanding rabbanim. When Lutzk was occupied by the Russians, they threatened to imprison him if he continued his activities, and so he fled to Vilna with his family, where Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski charged him with heading the Vaad Hayeshivos for the many yeshivos and talmidim who had escaped to Lithuania.

But Rav Sorotzkin knew that time was running out, and although he was no longer a young man (he was nearing 60), he was encouraged to escape with his wife and twin sons, Yisrael and Bentzion. As they boarded the train they hoped would take them to safety — and maybe even reach their goal of Eretz Yisrael — they cast a final glance at the cursed ground, and took stock of those remaining behind:

Their oldest son, Rav Elchanan, was caught by the Russians while escaping from Zholodek, where he served as rav, while his wife, Shaina, and their children were spared; their daughter Tamar (Temma) with her husband, Rav Yisrael Zeidenwurm, and their young son, who lived in Lodz; and their sons Boruch and Eliezer, who were in yeshivah in Telshe — all awaiting exit permits so that they could flee.

As the train set out toward Minsk, Rav Zalman promised himself he would find a way to remain in contact with each of his children, wherever they were.

Months later, after a chain of events that Rav Zalman would later describe as miraculous, the Sorotzkins would step foot on the ground in Haifa.

A festive reception to honor a man revered not just for his Torah, but for his communal responsibility, was held in the Babad Hotel in Jerusalem. Unable to just “enjoy the moment,” Rav Zalman shared the realities of what he’d seen in Europe and a disbelieving audience shivered in shock — and that was before the Germans had overrun Lithuania.

Rebbetzin Sarah Miriam Sorotzkin, who walked each day from their home at 10 Hoshea to the Kosel, pouring her heart out in prayer for her brothers and sisters, would not participate in simchahs and joyous events. Concern for those left behind consumed her.

But then, the letters began to come — a miracle in itself — and they tell a story all their own.

For 80 years, the collection of letters and postcards was kept private. But now, with the soon-to-be published first-ever book on Rav Zalman Sorotzkin’s multifaceted life — Bein Hadeah Ladibbur — the archives have been released by his grandson, Rav Michoel Sorotzkin, a popular lecturer and rosh kollel of Hadeah Vehadibbur Telshe Stone, who initiated the project to bring Rav Sorotzkin’s amazing accomplishments to a new generation. As a senior editor on the project, I’ve been privy to this collection, and am grateful to be able to bring them forth to Mishpacha readers for the first time.

To Marry or to Flee?

Erev Rosh Hashanah 5701, Telshe

On a postcard from Lithuania, the Sorotzkins finally get some news. In this first letter from their son Boruch, they learn about Boruch’s own life-altering decision: A shidduch was suggested with the daughter of the the gaavad of Telshe, Rav Avraham Yitzchak Bloch – he was actually Rav Zalman’s nephew, and Boruch’s first cousin. (Rav Yosef Yehuda Leib Bloch – his father, and Rav Zalman were both sons-in-law of Rav Eliezer Gordon. )

The deliberation was whether to flee at the first opportunity and forgo the shidduch, or perhaps to remain, but with the expectation to try to get to Eretz Yisrael with his future father-in-law. About three years earlier, the shidduch had been suggested during an encounter between Reb Zalman and his nephew, when the two had attended the Knessiah Gedolah of Agudas Yisrael in Marienbad, but now the question had burning practical ramifications.

Boruch first addresses the postcard “To Agudas Yisrael,” then erases it and writes again: “For Rav Sorotzkin, Jerusalem, Palestine.” The sender: B. Sorotzkin, Telshe, Lithuania:

“As the new year begins, I would like to bless you with the blessing of a very loving son, whose heart yearns to be close to those he loves,” Boruch Sorotzkin writes. “May it be Hashem’s will that very soon, He will gather in all the pieces of our family…

“On the one hand,” the letter continues, “I want to flee for my life and come to you. But on the other hand, the Gaavad of Telshe said that if I want, he will take me as a chassan for his older daughter, Ruchelle, tichyeh, and I will travel together with him to Eretz Yisrael.”

“Woe to me that I need to decide about my future on my own, and I do not have the advice of my dear parents,” he writes. “Even though Ruchelle has many mailos and she finds favor in my eyes, and especially because as the son-in-law of the Rav of Telshe I will have the ability to learn more Torah… on the other hand, they said that it will take a long time for this journey to happen, and I do not want to remain here.”

“Please, dear parents, tell me what to do, and if you think I should not wait, and should come to Eretz Yisrael, then send a telegram that I should do so. If you do not reply as such, then it will be a sign that you agree that I should wait with the Gaavad shlita.”

In response to the question, Rav Zalman sent a letter to the father of the intended kallah — his nephew Rav Avraham Yitzchak Bloch, sharing his warm agreement to the shidduch. Rav Avraham Yitzchak replied that although it was true that Boruch was younger than his brother Eliezer, who was also a talmid in the yeshivah, and it was usually appropriate to wait and not bypass a brother, at a time of war, the situation is different.

Indeed, the wedding took place in the winter, and the Sorotzkins were updated about it after the fact.

After the sheva brachos, it was time for the fateful decision. Rav Avraham Yitzchak writes to his aunt and uncle — his new mechutanim: “The dear children traveled from Kovno on Wednesday and today we received a telegram… that they arrived safely. We decided that they would travel east, after we received knowledge that they had received entry permits to the United States.”

He adds an enthusiastic description of the wedding, relating that the chassan delivered “lofty chiddushei Torah… and there were derashos full of depth and encouragement.”

And so, the concerned parents in Eretz Yisrael learned that the young couple, together with Eliezer, departed immediately at the end of sheva brachos with a group of talmidim on the journey to freedom.

Safe for Now

The first piece of information about the escape arrived in the Holy City from Eliezer: “Wednesday night, Beshalach, 11 p.m. We have just arrived in Minsk. The journey was fine, baruch Hashem. We have to spend four days here until we can depart for Vladivostok… I must make place to write for Boruch and Rochel. Yours, Eliezer.”

Boruch takes over, writing from where his older brother had stopped. The last part of the postcard was signed by the new kallah, Rochel, who wrote: “I also wish to add a few words to this card. But because space is tight, I will suffice with warm regards. Baruch Hashem we are already up to here… Let us hope He will take us on the successful path going forward.”

At the end of a long and exhausting journey through several time zones on the nearly 6,000-mile-long Trans-Siberian Railroad, the escapees reached a small Japanese ship, which took them to the port of Kobe, Japan.

They’d received a few of the thousands of transit visas to Japan issued by the righteous gentile, Japanese envoy Chiune Sugihara, which would be valid for just a few weeks in the country. The local Jewish community lobbied for the refugees and succeeding in extending the date of the visas by promising that the group would soon leave.

On the official stationery of the Nitsbi Hotel in Yokohama, the young Sorotzkins wrote of their journey, and also included some information about their brother Elchanan and his wife, and their sister in Lodz.

Not all letters got to their destinations, though; many would be lost or confiscated in transit. But it seemed that somehow, the really important news reached their target. Boruch writes from Kobe, Japan: “A number of weeks have passed since we received any news from you, even though we have twice received posts from Eretz Yisrael in these days…” He relates that only his wife, who was born in Kharkov, received a visa to the United States (Japan had not yet entered the war against the US). She consulted with leading talmidei chachamim, and they instructed her to travel alone and not to wait for her husband or the rest of the group. Whoever was able to flee, should flee. Boruch writes: “We are almost giving up on our trip to the United States, but now that dear Ruchelle has traveled alone there, perhaps if Hashem wills it, she will be able to arrange our emigration there.”

One postcard arrived in Eretz Yisrael telling of the ongoing correspondence between the brothers in Shanghai and their oldest brother, jailed in Russia. At that point, they realized that Rav Elchanan’s incarceration was a blessing, because he was being guarded by the Russians.

Double Shabbos

The brothers write to their father about the complications of Shabbos in relation to the dateline. According to the Chazon Ish, Japan is on the same side of the dateline as the United States, meaning that when the Japanese say it’s Saturday, halachah says it’s Friday. When they say it is Sunday, it is halachically Shabbos. Eliezer explains: “Last week, we received a telegram from the Chazon Ish in Bnei Brak that we have to observe Shabbos like in America, which means Sunday here. And being that until now, we kept Shabbos the same day as in Europe, we are now strict to keep Shabbos for two days.”

They relate that that first Shabbos — which according to the Chazon Ish was to be treated as Friday — the mashgiach of Yeshivas Mir, Rav Yechezkel Levenstein, entered the beis medrash and began davening Maariv of weekday.

Once the group notified Rav Zalman that they’d reached Shanghai, China, Rav Zalman wrote back suggesting that at least one of them try to get to Australia, where they might be able to get visas. Some Telshe students had managed to escape to Australia, where they were welcomed by the small Jewish community in Brisbane. But Eliezer wrote back that they were strict not to travel to Australia because of the same Shabbos issue: “In many of the towns there, most of which are on the coast, it has not yet become clear to this day which day is actually Shabbos… It was very hard when we were in Japan, and many people fasted two days for Yom Kippur.”

And then, the letter that arrived in Elul 5701 from Rochel said it all.

The stamp was American.

“I have not written to my dear ones for a long time, because for the past few weeks I was traveling. You surely know already that I had to part from Boruch, and how much pain and anguish this separation has caused me… But I have to be strong and trust in Hashem that He will hear my tefillos and will unite us again very quickly.”

She also describes the miracles of her voyage, how the ship kept returning to Japan for various reasons, and how, although the final destination was San Francisco, she decided to get off at the first stop when the ship docked in Honolulu, Hawaii. In the end, the ship never made it to San Francisco – it turned around and went back to Japan. Rochel discovered some good Jews in Hawaii who helped her get to Los Angeles, and from there she eventually made her way to Cleveland, where she was reunited with her relatives – Uncle Eliyahu Meir and Rav Gifter and his wife (daughter of her uncle Rav Zalman Bloch), who was her first cousin.

As time passed, the Sorotzkins received more and more letters from Shanghai and the United States, and far fewer from Lithuania and Poland. But amid the constant worry and panic for the rest of their family, one piece of good news arrived: Reb Eliezer was engaged to Chasya, the daughter of his uncle Rav Eliyahu Meir.

Regards from Moscow

Rav Zalman and his wife waited and prayed throughout the war years. And then finally, they received a letter from Elchanan in Moscow, released from prison after five years.

“To my dear loved ones!

“On the great day of victory of the Allied forces, led by the heroes of the Red Army, I wish to bless you from the depths of my heart. (These descriptions were, of course, also meant for the eyes of Russian censors.) I wrote to Piotrkov regarding Temma — who knows, perhaps she is still among the living. We have recently discovered many people who were in captivity and in the concentration camps of Hitler and the murderers, who were thought to be dead, and there were even eyewitnesses who saw their deaths… Maybe.

“With regard to Shaina and my children, there isn’t even a shred of hope… In the area where she was, the first massacre took place — they didn’t bother taking anyone to the camps, they just killed them. Still, I cannot, deep inside, come to terms with the idea that they are not among the living…”

Shattered and brokenhearted, Rav Elchanan wanted to travel to Eretz Yisrael, but there was one thing that he lacked in order to be able to leave Russia: a Polish passport. He could not obtain it as long as the war was not officially over and there was no government functioning in Poland. Rav Zalman, however, poured out his heart in letters to consuls around the world. In time, following his release, Rav Elchanan was appointed nasi of Agudas Yisrael in Poland, and after wandering from Lodz to London, he would finally come to Eretz Yisrael. There, he married Rebbetzin Tzila Orlean, a talmidah of Sarah Schenirer and an angel of mercy to so many in the concentration camps.

At the time, Rebbetzin Rochel and her husband, Rav Boruch, who managed to get to America and who became a rebbi in the new Telshe Yeshivah in Cleveland, were trying to get information from Telshe, sending letters together with money. “We are waiting,” Rebbetzin Rochel writes to her in-laws in Eretz Yisrael, “to hear from our dear loved ones and hope that there will be happy news…” She had no idea that the kedoshim, including her father, were taken to a brutal death right near the town.

(In Cleveland, Rav Boruch and Rebbetzin Rochel closed a long-open circle: When Rav Eliezer Gordon passed away in 1910, it was assumed that his two sons-in-law, Rav Zalman Sorotzkin and Rav Yosef Leib Bloch, would split the responsibilities of rav and rosh yeshivah of Telshe. But Rav Sorotzkin, not wanting to create any kind of competition or machlokes, moved away and gave the entire position to his brother-in-law. Now, a generation later, in the newly transplanted Telshe, Rav Zalman’s son and Rav Yosef Leib’s granddaughter – Rav Boruch, with Rebbetzin Rochel Sorotzkin at his side – led the yeshivah.)

The Heart Dies

Only in 1945, would the survivors begin to realize the extent of the churban. How entire communities had been wiped out, including the community of Lutzk, where tens of thousands of Jews were slaughtered.

Rebbetzin Shaina Hy”d was murdered in Novardok in Kislev 5702, along with her daughter, Liba, and her son, Bentzion, whom his father had never even seen — he was born a short time after Rav Elchanan was imprisoned.

Temma and her young son, Bentzion Hy”d, were deported to Treblinka in Cheshvan 5702/1941. Testimonies described how after she lost her husband, Rav Yisrael Zeidenwurm Hy”d, shot by the Nazis in the Lodz ghetto, Rav Moshe Chaim Lau, the rav of Piotrkov, suggested that she utilize the fact that she could pass herself off as an Aryan Polish woman and escape from the ghetto to the Polish side. But having been raised in her father’s house, she said that it was inconceivable that all the Jews would remain in the ghetto and she would ostensibly become a Christian.

How does one react upon receiving news of both salvation and destruction? By war’s end, Rav Zalman Sorotzkin was both devastated and grateful — half his family perished, while the others miraculously survived. But despite the travails of his own life, he couldn’t remain inactive for even a moment. He became chairman of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah of Agudas Yisrael, and when Chinuch Atzmai was formed in 1953, he was chosen to head it.

The Torah world needed him, and heeding the call, he immediately departed for Britain, and later, his wife joined him for an extended period of time in America. While there, they missed the wedding of their son Yisrael, but Rav Zalman and Rebbetzin Sarah Miriam were already accustomed to participating from afar.

In a letter written from London to his wife in Eretz Yisrael, Rav Zalman writes: “You, dear Miriam, are complaining that on Shabbos and Yom Tov my absence is felt. But what can we do if I am a shaliach mitzvah, and there is a great mitzvah to support Torah in Eretz Yisrael? What is human life in This World if not to work to honor Hashem and His Torah?

And that was his living will, the light that he followed in war and in peace, in calm times and stormy ones: “What is human life in This World if not to work and honor Hashem and His Torah?”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 861)

Oops! We could not locate your form.