And Nochum Walked Alone

| March 10, 2021He was friends with everyone. His only son was friends with no one

"Pass the kichel,” Yehuda told Moish Taub. “I’m starving.”

Kehillas Kol Yaakov was thrumming with noise and movement. Men and boys passed around baskets of Tam-Tams and containers of herring, elbows bumping and napkins flying.

Taub grinned and handed him the platter. “Don’t fill up too much,” he warned Yehuda with a mock-serious face. “The cholent hasn’t come out yet.”

Eli, Taub’s eldest, rolled his eyes. “You always tell us that,” he said.

“Yeah,” Binyomin, Taub’s second son, laughed. “I think it’s getting old, Ta.”

Yehuda frowned, looking around. “Have you boys seen Nochum?” he asked the Taub kids.

Eli shrugged. “Not sure,” he said. “Maybe I saw him reading in the coat room?”

Yehuda cringed. Reading? In the coat room? He looked at all the fathers and sons around him, eating, laughing, enjoying. They seemed so…normal. Something in his throat tightened.

A voice shook Yehuda out of his bleak reverie. It was Fried-from-the-downstairs-minyan. “Did you order Nochum’s tefillin yet?” he asked. “His bar mitzvah is this year, right?”

“Please don’t get him started,” Taub moaned. “Does he ever talk about anything else?”

Yehuda ignored him. Even as he grinned at Fried, he felt that familiar stab of pain in his chest. “You better believe it,” he said.

He’d been dreaming of Nochum’s bar mitzvah for years. Even Nochum’s early diagnosis as “on the spectrum” couldn’t steal this milestone from Yehuda. This was his only son after all. But the thought of the simchah without Aidel…Yehuda clenched the napkin in his hands until his knuckles turned white.

It had been five years already, and while Yehuda had mostly settled into his subdued single existence, planning the bar mitzvah he and Aidel had so anticipated was bringing so many memories into painful relief.

No one had to know that, though. So he just clapped Taub on the shoulder and said again, “Yup, it’s going to be something big.”

Taub rolled his eyes and helped himself to some more herring. “Don’t forget to send me an invite — I like a modest simchah. You know where I live.”

“C’mon, you know it’ll be huge,” Gross-the-Chase-points-guy said, laughing. “I’ve had the date marked since the shalom zachor.”

Yehuda laughed too, while wondering if everyone around him was really oblivious to his mixed feelings about the upcoming simchah.

He thought of Nochum reading in the coat room, and realized he’d never really discussed the plans for the bar mitzvah with his son. He’d have to do it soon, before finalizing arrangements with the hall. He had an uneasy feeling about the conversation, but tried to push it to the back of his mind. Which 12-year-old didn’t want a show-stopping bar mitzvah?

Nochum’s jaw was set and his gaze strong as steel as he sat cross-legged on his bed. “I am not having a birthday party.”

He refused to meet Yehuda’s eyes, and instead stared at the clock that hung across from him. It had been a present from Aidel’s mother for his tenth birthday and was decorated with colorful mathematical equations.

Yehuda ran his hands through his hair, exasperated. “It’s not just any birthday,” he said, struggling to maintain a reasonable tone. “It’s your bar mitzvah.”

Didn’t Nochum realize what he was doing to himself, how he was cutting himself off from the rest of the world? Why did he have to be so difficult, and so, so… ungrateful!

Nochum emphasized his words slowly and clearly, the way they taught him in speech therapy. “I. Don’t. Care.” He folded his arms and turned around on his bed. The back of Nochum’s faded T-shirt — a picture of an astronaut — was staring Yehuda in the face, mocking him.

Moish Taub’s sons would be ecstatic if they were offered a bar mitzvah like this, a little voice whispered.

Hey, don’t compare, he scolded himself.

Yehuda breathed deeply and tried again.

“Nochum, just think about how nice it’ll be.” Yehuda’s eyes were wide as his imagination started to run wild. “We’ll have a banquet and guests and all your friends can come!” Please, Nochum, Yehuda begged silently. Do this for me. Be like other kids.

Why don’t you ever let loose and have a little fun?

Silence. “I don’t have any friends,” Nochum finally said in a monotone, still staring at the wall.

Yehuda exploded. “Well, maybe if you didn’t spend all your time reading in a coat closet, you’d have some friends to invite! Maybe if you ever had some guys over, then you wouldn’t be so, so — so absolutely stubborn about not having this party!” Nochum flinched, like he’d been slapped. His shoulders started to shake, and though he could only see Nochum’s back, Yehuda could hear him quietly sobbing. His eyes widened. What had he done?

“Sorry, buddy,” Yehuda said quietly, but it was too late for apologies. He walked gingerly across the room. Yehuda felt sick; Nochum hadn’t deserved that. But what was he going to do with him? Did Nochum really not care that he had no friends? As his father, it was Yehuda’s job to save Nochum from himself.

Aidel would’ve handled this conversation better, he thought, that familiar twinge shooting through him. Closing the door of Nochum’s room softly, Yehuda walked toward his bedroom, alone with the thoughts swirling around his head in the silent, enveloping darkness.

It was Sunday afternoon, which meant the same thing it always had for the past ten years: therapy. Only for the past five years, it had been Yehuda taking Nochum to his sessions instead of Aidel.

Nochum’s gaze was fixed out the window, and Yehuda tried to think of something to talk about, when suddenly Nochum spoke up. “The coronavirus isn’t only in China anymore.”

Yehuda’s brow furrowed. Taub and Fried had mentioned coronavirus at the kiddush last Shabbos; both of them seemed to think it was a big joke. But Yehuda was sensitive to anything illness-related, and his thoughts immediately turned to his mother. She’d had already had pneumonia twice and this couldn’t be good news. “Where has it spread to?”

Nochum started swaying back and forth. “Under 15 cases in Albania,” he said, his voice a monotone. “62 cases in Algeria. 13 cases in Andorra.” Yehuda’s hands gripped the steering wheel like a lifeline. Pictures of Aidel in ICU flashed through his mind, and he superimposed them with images of foreigners in masks. Frightening terms like respirators and organ failure swirled in his mind. His head hurt. “Stop,” Yehuda said forcefully.

Nochum didn’t hear him.

“2 cases in Angola. 0 cases in Antigua and Barbuda. 41 cases in Argentina—”

“Where did you get those numbers from?” Yehuda asked, cutting him off.

“I memorized them,” Nochum replied, “when I was bored.”

Yehuda sighed, frustrated. His son spent more time with numbers than with people.

“You know, you could invite a friend over some time,” Yehuda suggested.

Nochum shook his head. “No one will want to come. Besides, I like being on my own.”

I like being on my own.

Yehuda remembered the day he’d gone to Nochum’s kindergarten, eight years ago. Aidel had usually taken Nochum to school, but she’d been in a rush that morning, so Yehuda had had the honors. He’d walked into the preschool, holding Nochum’s small hand, the only man in a sea of busy mothers. He reached the kindergarten classroom, and Morah Henny had smiled at Nochum. Yehuda had hung back a minute, curious to see Nochum in a different environment.

He watched as his small son found his way to the toys, taking out a puzzle that depicted a colorful circus. As he started to spread out the pieces on the floor, another small boy with a red daled on his yarmulke sat down next to Nochum, attempting to join him. Nochum startled, and started flapping his hands and rocking back and forth, clearly distressed.

No, Yehuda thought. No no no. He had watched in horror and frustration, helpless, as the child had run away. Nochum was so young — didn’t little kids love to play with each other? What was the matter with him?

Yehuda looked back at the road, letting the memory fade. He glanced over at his son, now eight years older, and shook his head — not much had changed.

Now curious after Nochum’s briefing, he slowly turned up the radio.

Yehuda hated this despicable virus.

At first, quarantine hadn’t been so bad. He had his Keurig at home, not the terrible instant coffee they offered in the office, and now that he worked from home, he didn’t have to listen to Glick-from-management drone on for hours about why the stock market was about to crash.

But the silence was getting to him. No minyan, no shul kiddush, and no office. His house seemed hollow and empty, its only inhabitants a 39-year-old man and an autistic child with speech delays.

Yehuda had tried reaching out to friends, but the difference between his solitary reality and the busy lives his friends led had never seemed so stark.

“Hello?”

Yehuda leaned back into his favorite swivel chair, breathing a sigh of relief. “Taub,” he said with a grin, “Mazel tov, you finally pick up your phone! How’s it goin’?”

“Fine, fine, baruch Hashem.” Taub had sounded more distracted than usual. In the background, Yehuda could make out some vague shrieking. “Actually, Yehuda — can I call you back? My wife — Boruch, stop screaming! — needs help getting the, uh — I’m coming, Chavi! — getting the kids to sleep, and then I’m learning with Klein. It’s not urgent, yeah?” Taub had paused, waiting for a response.

“No problem, Moish,” Yehuda had said, “no problem at all.” But he hung up the phone with a tenseness that belied his words.

Neuman was a doctor, so he was on call pretty much all day. Fried and Gross had meetings and clients to deal with from nine to five, and their wives were desperate for their help afterward. Even Glick was busy, and his disappointment on hearing that was frighteningly telling.

It was yud-zayin Sivan. Aidel’s yahrtzeit once more.

Yehuda drove to the cemetery in the morning. The roads were empty and the air was cool with a breeze. Nochum would come later, with Yehuda’s brother-in-law Dov. Now Yehuda needed to be alone.

He weaved his way through the matzeivos, some covered with rocks, some bearing just a pebble or two. The path was familiar; he could walk it in his sleep. Soon he was standing in the right place.

“Hi, Aidel,” Yehuda said quietly. The wind whistled through the trees.

Yehuda said some Tehillim, the familiar words soothing him. There would be no minyan this time. No Kaddish, either. He knew it wasn’t his fault. But it still hurt.

Yehuda kissed his siddur and gently closed it, then breathed a heavy sigh. “Aidel,” he said quietly, “I need your advice. I don’t know what to do with Nochum.” His voice was thick as he choked out the words. “Every day, he’s regressing.”

He knew it from the abbreviated speech, the way Nochum didn’t leave his room anymore, even for meals. When he’d go to his room and try to start a conversation, Nochum’s sentences were clipped and expressionless. He just sat on his bed, staring at the ceiling.

A tear slid down Yehuda’s face, followed by another, then more; he covered his face, but the tears dripped through his fingers, wetting his collar. He was worried about Nochum, so, so worried. “He doesn’t have real friends, Aidel. He doesn’t even want a bar mitzvah. Our son is all alone.”

Alone. Alone. The words echoed in his brain, clattering against his head.

Nochum is all alone.

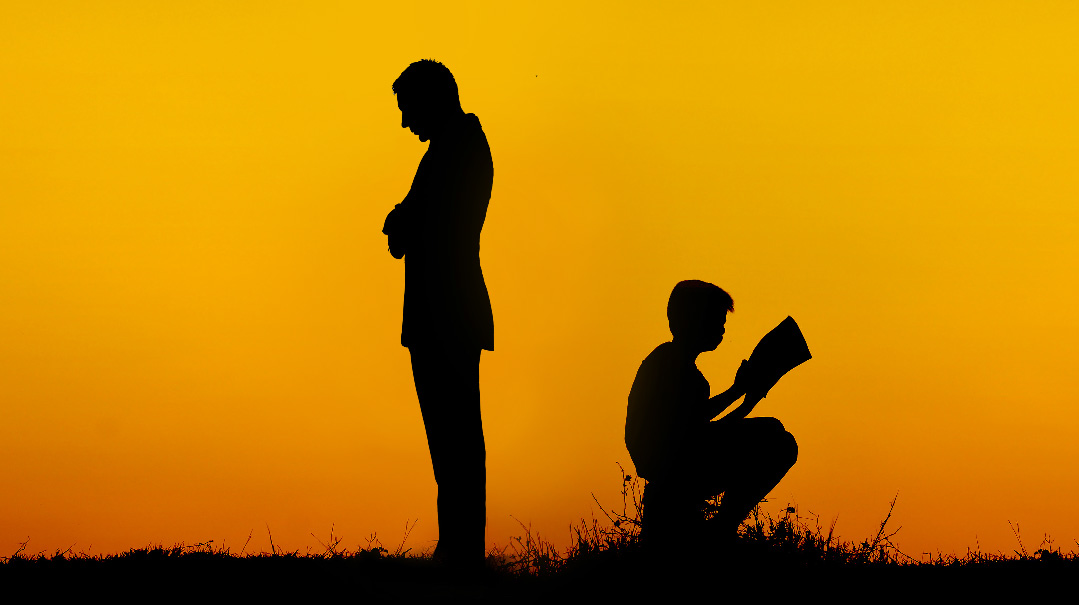

That’s when it hit him. He was Nochum. He had become Nochum.

He had 50 friends on his contact list, always had someone to hock with at the shul kiddush, never lacked for a Shabbos invitation, and he was all alone.

He’d tried to drown out the aching void of a wife who was gone and dreams of a son with loud friendships and a busy social life that would never materialize, but inside there was still a chasm. Most of the time he didn’t dwell on it. But now — now there was no avoiding it. He was alone.

He inhaled sharply. Was this what Nochum had been feeling his whole life? Was this what it was like for him, to be cut off from the world, standing so near, but never really being let in, close enough to hear what was being said, but not fluent enough to join the conversation?

COVID had sent everyone home, helping their spouses, dealing with their kids. All of his friends were grappling with this new challenging reality, but they were facing it as families; as parents and children, as spouses. But where did that leave Yehuda?

Bitter. Bitter and resentful and so, so alone.

Again he thought of Nochum, and his heart ached.

It had been nearly 13 long years; over a decade of hurt feelings, sore hearts, and misunderstandings. Countless months of living in a house with someone who shared his last name and DNA, but was miles apart from him in every other way. And he was the one to blame. He’d never taken the time to try to understand his son, and their relationship had withered.

He didn’t want that anymore.

Yehuda was determined to develop a relationship with the stranger he called his son. He’d always loved Nochum. Now he would try to understand him, too; to be together, to be with him in this.

For so long, they’d been trekking parallel paths; it was time for them to begin traveling this turbulent journey of life together.

After all, they weren’t so different. So why should Nochum walk alone?

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 734)

Oops! We could not locate your form.