Supremely Protected

Why the Agudah took Cuomo to court: The story behind the scenes

Amid all the personal tragedy and economic hardship the coronavirus pandemic has wrought, it has been difficult to discern points of light and hope in the communal darkness. But they’re there: The emergence with unprecedented speed of several effective vaccines was one such ray of light.

And another light has recently shone forth, this time not from laboratories but from the highest courts in the land, lifting the spirits of frum Jews throughout America. Two legal rulings — first by the United States Supreme Court and a month later, by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, the New York region’s top federal court — resoundingly affirmed the rights of Americans of faith to practice their religions free of severe, ostensibly health-related restrictions targeting them, even amid the pandemic.

The import of the sea-change inherent in these decisions was not lost on the legal world. “When the history of this era of the Supreme Court is written, we may look back at [this] ruling as the fountainhead of a massive shift in how a majority of the Court approaches religious liberty… It really is a huge deal,” said Professor Stephen Vladeck, professor of law at the University of Texas at Austin and a leading constitutional law scholar, when word of the Supreme Court ruling broke shortly before midnight on November 25. And in the short time since the ruling, it has already served as the basis for a half-dozen court decisions advancing religious freedom in California, Colorado, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, and Ohio.

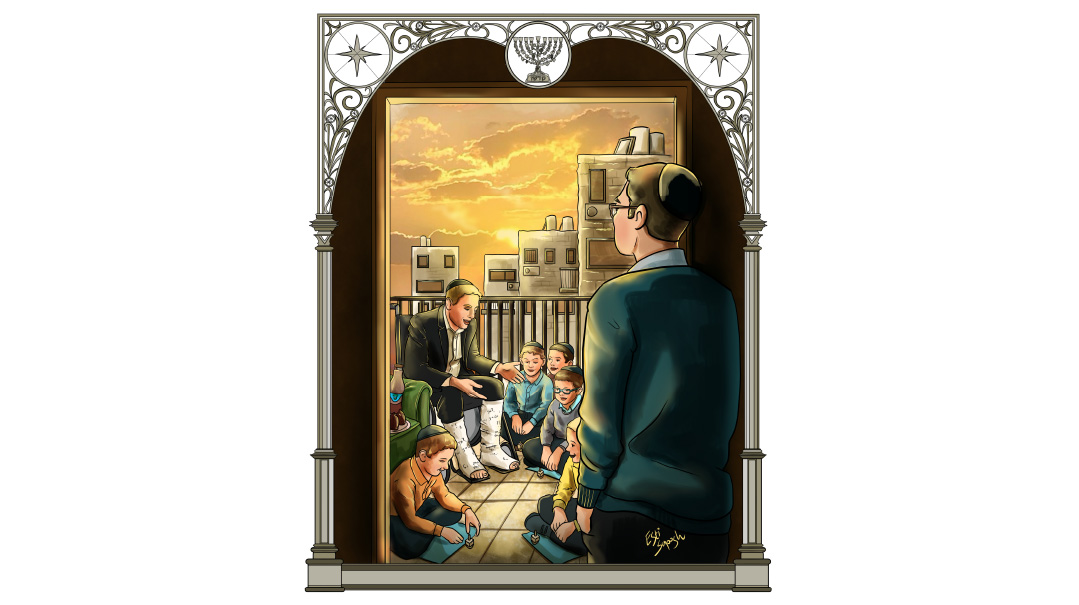

The Supreme Court and Second Circuit decisions were the happy endpoint of a saga that had had its beginnings many weeks earlier, on Hoshana Rabbah. This last day of Succos is a special time, replete with special mitzvos — hoshanos, the final taking of the arba minim, and a last chance to make a leisheiv b’succah — and always, with a hint of anticipatory excitement in the air for the approaching high festivities to cap zeman simchaseinu.

But like so many things that were different in this Year of the Plague, that expectant enthusiasm was gone, replaced by a very heavy sense of foreboding for what the last days of Yom Tov and the weeks beyond would look like. Just three days earlier, New York’s Governor Andrew Cuomo had issued a far-reaching, unprecedented executive order (EO) by which, with one stroke of the pen, he threw the state’s frum Jews into grave doubt about whether Shemini Atzeres and Simchas Torah could be celebrated with any semblance of normalcy.

On one of the most joyous days on the Jewish calendar, shuls in numerous Orthodox neighborhoods throughout New York and beyond would be subject to restrictions that would leave them effectively shuttered. The EO had caught the frum community entirely by surprise, since just hours earlier, on a phone call with community leaders to discuss an uptick in COVID cases in the state, the governor had agreed that shuls and other houses of worship were permitted to operate at 50% capacity.

But later that afternoon he abruptly switched course, rolling out what was termed a “cluster action initiative” to address COVID-19 hot spots in Brooklyn, Queens, and several upstate counties including Rockland, where large frum communities exist. These areas were divided into three categories: “Red zones,” where attendance at houses of worship was limited to the lesser number of either ten people or 25% capacity, with essential businesses remaining open and schools ordered closed; “orange zones,” where attendance at houses of worship was capped at the lesser of 25 people or 33% capacity while essential businesses were permitted to operate; and “yellow zones,” where houses of worship were allowed 50% capacity, and businesses and schools could remain open. In all three zones, a category of undefined “essential gatherings” was permitted without any limitations.

Simply put, this EO meant that in some neighborhoods, only a literal minyan of men, and in others two minyanim and a half, would be permitted to gather in shuls for Yom Tov davening, hakafos and all the rest — regardless of whether it was a cramped basement shtibel or a capacious shul with seating for many hundreds. Given the governor’s past practice, the restrictions were expected to be renewed and extended — as in fact occurred — meaning that schools would not be able reopen as usual after the conclusion of Yom Tov and shuls would remain severely restricted.

News of the announcement, a bolt out of the blue in mid-afternoon on the second day of Chol Hamoed sent New York’s frum community reeling, the jubilant advent of Yom Tov suddenly turning morose and uncertain. But immediately, it also set off a flurry of phone calls between a group of askanim and rabbanim about what the response should be and who should lead it. They all agreed: This was a mission for Avi Schick.

A partner at the law firm Troutman Pepper, Avi is a longtime legal advocate on behalf of New York’s Orthodox Jewish community, most recently helming the successful “substantial equivalency” litigation that stopped New York State’s education department from imposing radical changes in yeshivah curricula. Schick knew that it would be essential for Agudath Israel of America, with its long experience in religious liberty cases, its political savvy and its unrivaled reputation in the frum community, to come on board.

Given the sensitive matter of whether to precipitate a head-on clash between the governor and the country’s largest frum community, he knew it would be crucial to receive a go-ahead from Agudath Israel’s ultimate decision-making body, the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah. But with the approaching last days of Yom Tov less than 72 hours away, Schick also knew he needed to forge ahead and have a lawsuit ready to go in the event the members of the Moetzes would place their imprimatur on it.

Three Agudah shuls in Brooklyn and Queens, together with their rabbanim, agreed to serve as plaintiffs. Schick and his colleagues spent the next 48 hours drafting legal briefs and court papers, amassing relevant health data and preparing affidavits. The goal was to file on Thursday morning so that they might obtain an emergency temporary restraining order (TRO) and preliminary injunction against Governor Cuomo’s implementation of the EO in time for Hoshana Rabbah.

While the Agudah’s lay leaders waited for a signal from its rabbinic leadership, it issued a statement making clear that the governor had crossed an unacceptable line: “Governor Cuomo’s surprise mass closure announcement today, and limit of 10 individuals per house of worship in ‘red zones,’ is appalling to all people of religion and good faith. We have been down this path before, when religious practices were targeted for special treatment by the Governor’s Executive Order in May…. and the court found it unconstitutional. Repeating unconstitutional behavior does not make it lawful. Agudath Israel intends to explore all appropriate measures to undo this deeply offensive action.”

For Agudath Israel, suing the State of New York in court was not its first choice. It traditionally prefers to eschew confrontation with the elected officials and government on whom the Orthodox community relies. And in this case, there was also a more personal element: Shlomo Werdiger, chairman of Agudath Israel’s board of trustees, had a long-standing, close relationship with Andrew Cuomo.

As Avi Schick observes, “There has long been this stereotype that the more chareidi the organization, the more transactional it is and the more its interactions with government are based solely on dollars and cents. This case, where the Agudah risked relationships in pursuit of important principles, surely proves that to be untrue. Not every organization has shown itself willing to do the same.”

A great deal of the credit for moving ahead with the challenge, according to Rabbi Chaim Dovid Zwiebel, Agudath Israel’s longtime executive vice-president, “goes to Mr. Werdiger, who has developed a personal relationship with Andrew Cuomo over I-don’t-know-how-many years, and hosted the three-term governor in his home and office on numerous occasions. He nevertheless understood that all that we do at the Agudah is based on the guidance of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah and he remained totally deferential to their decision.”

Rabbi Zwiebel recalled that at one point during the litigation, “I walked into a meeting with the roshei yeshivah having one perspective, and the roshei yeshivah present took a contrary perspective — and that was it. It reminds me of a classic Rabbi Sherer story in which he walked into the room to present his position to the Moetzes, and after they decided to do just the opposite of what he proposed, he walked out all gung-ho to carry out their directives, and remarked, ‘This is the kind of day I live for.’ ”

Reflecting on the decision of the Moetzes to proceed with the lawsuit, Rav Elya Brudny, rosh yeshivah in Brooklyn’s Mirrer Yeshivah and a Moetzes member, says that “the decision was made with a tremendous amount of kevod rosh that we are acting out of character for how we normally act in galus. Reb Chaim Dovid’s advocacy was not based on politics and strategy, but was based instead on considerations of kiddush Hashem and chillul Hashem. Kevod Shamayim was at stake.”

And so it was that Avi Schick found himself standing on the morning of Hoshana Rabbah — judgment day for the nations of the world — before a federal district court judge in the Eastern District of New York, seeking a TRO against Governor Andrew Cuomo. But it was not to be. At the conclusion of the hearing, the judge issued an oral ruling denying the petitioned-for relief. The court asserted that the plaintiffs’ claims that their constitutional rights to freely practice their religion were unlikely to succeed because courts must defer to the States in these matters, and that, in any event, the inability to attend worship services does not impose irreparable harm because people can continue to practice their religion “with modifications.”

The depressing news of the TRO denial two hours before the onset of Yom Tov drove Shlomo Werdiger to tape a short video message, widely viewed on communal news websites, in which he vowed that the Agudah would press forward with an appeal.

That Simchas Torah became a landscape of makeshift minyanim and harried hakafos. Some shuls moved the davening and dancing outdoors, while others had hakafos with no dancing. Still others tried to maintain a semblance of normalcy even as their mispallelim feared the sudden appearance of state inspectors ready to impose the threatened $15,000 fines on noncompliant congregations.

With the conclusion of Yom Tov, Avi Schick and his team set about drafting appellate papers, and on October 21 they filed an emergency motion for injunction pending appeal in the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. In a departure from its usual procedure, the Court ordered full briefing and oral argument in front of a three-judge panel on the motion. The Court also combined the hearing with that of the Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn, whose own suit against the EO had failed at the district court.

On November 9, the Second Circuit denied the injunction in a 2-1 decision. It was then clear that the only recourse would be to present the case to the United States Supreme Court. The Diocese and the Agudah both filed emergency requests for an injunction pending appeal with the high court.

While the Agudah and Diocese suits were similar, there were several important differences. The Diocese challenged only the ten- and twenty-five-person attendance limits, and sought permission only for Diocese churches to operate at greater capacity. The Agudah had broadly challenged the governor’s order, arguing that Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods and religious institutions have been — in the words of the Governor himself — “targeted.”

In the words of the suit, “The Governor publicly asserted that other Orthodox Jews had violated his prior rules, and therefore the Governor imposed severe restrictions on worship across several Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods. Applicants themselves are not alleged to have violated any public health or safety rules… None of this is necessary to protect public health. The Governor has admitted that the restrictions are not based on science, but rather on ‘fear’ and ‘emotion’ about areas that would be ‘safe zones’ in other states.”

The prospects of a positive Supreme Court ruling were far from certain. In May and again in July, the Court had considered applications for emergency injunctions against pandemic-related limits on religious gatherings imposed by California and Nevada. But in both cases, a 5-4 majority of the Court, comprised of Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor had denied the relief sought.

“From the get-go,” Mr. Schick says, “We understood this was an uphill battle, because the Supreme Court had previously rejected challenges similar to ours. So it took courage on the part of the Agudah, because this was no slam-dunk case. They did the right thing because it was right, not because it was easy.”

Still, there was reason to believe this time might be different. The Court’s composition had changed, with the addition of Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who took the seat that opened with the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg two months after the July ruling.

And in the end, this time was indeed different. Late on Wednesday night, November 25, the Supreme Court, in a per curiam, or unsigned, opinion supported by Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Barrett, blocked enforcement of Governor Cuomo’s restrictions on houses of worship, based on the plaintiffs’ “strong showing that the challenged restrictions violate ‘the minimum requirement of neutrality’ to religion.” The Court was emphatic that “even in a pandemic, the Constitution cannot be put away and forgotten. The restrictions at issue here… strike at the very heart of the First Amendment’s guarantee of religious liberty.”

The Court held that the restrictions could not “be viewed as neutral because they single out houses of worship for especially harsh treatment,” with synagogues and churches in “red zones” subject to capacity limits while “essential” businesses, such as supermarkets, pet stores, liquor stores, laundromats, and banks, were not. In “orange zones,” the opinion observed, the “disparate treatment is even more striking… While attendance at houses of worship is limited to 25 persons, even non-essential businesses may decide for themselves how many persons to admit.”

The only explanation for treating religious venues differently, the Court observed, “Seems to be a judgment that what happens there just isn’t as ‘essential’ as what happens in secular spaces. Indeed, the Governor is remarkably frank about this: In his judgment, laundry and liquor, travel and tools, are all ‘essential’ while traditional religious exercises are not. That is exactly the kind of discrimination the First Amendment forbids.”

Once it had determined that the governor’s restrictions were not neutral, the Court proceeded to the next level of analysis. Under well-settled First Amendment jurisprudence, a law that is not neutral in its restriction of religious practice can only be justified if it survives “strict scrutiny.” This means it must be “narrowly tailored” to serve a “compelling” state interest, by using the “least restrictive means possible” to advance that interest.

Although the Court granted that the New York restrictions enacted to stem the spread of COVID–19 unquestionably served a compelling interest, it found it “hard to see how the challenged regulations can be regarded as ‘narrowly tailored’… They are far more restrictive than any COVID–related regulations that have previously come before the Court, much tighter than those adopted by many other jurisdictions hard-hit by the pandemic, and far more severe than has been shown to be required to prevent the spread of the virus at the applicants’ services.”

Expanding on the notion that Cuomo’s limitations were not narrowly tailored, the Court said “there are many other less restrictive rules that could be adopted to minimize the risk to those attending religious services. Among other things, the maximum attendance at a religious service could be tied to the size of the church or synagogue… It is hard to believe that admitting more than 10 people to a 1,000-seat church or 400-seat synagogue would create a more serious health risk than the many other activities that the State allows.”

The Supreme Court issued an injunction pending, and the case returned to the Court of Appeals for a consideration on the merits. Numerous organizations submitted briefs as amicus curiae (friend of the court) in support of Agudath Israel’s position, but one that Avi Schick singles out for particular praise came from a surprising quarter: The Muslim Public Affairs Council.

In its brief, the group argued that “too often, religious minorities have served as scapegoats in times of sickness, war, and fear… Latest in a long and troubling line of such incidents are the statements and policies of Governor Cuomo blaming Orthodox Jewish communities for the spread of COVID-19 and specifically targeting them for closures and restrictions, all despite a dearth of evidence… The Government’s accusatory rhetoric is fanning the flames of an already precarious position for the City’s Orthodox Jews, and this irresponsible behavior can have deadly consequences. This Court should strike down government policies that are rooted in and encourage such dangerous religious hostility. The First Amendment demands nothing less.”

On December 28, a three-judge panel issued its decision in the combined appeals of Agudath Israel and the Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn, ruling unanimously that numerical caps in Governor Cuomo’s order were unconstitutional, determining that the percentage caps are subject to strict scrutiny, and remanding to the district court the question of whether the percentage caps can satisfy that standard. The court held that although the Supreme Court’s opinion had addressed the fixed capacity limits, its reasoning would also require that the percentage capacity limitations be subject to a strict scrutiny analysis, which they could not survive.

Although it found that the EO “discriminated against religion on its face,” the appeals court took pains to note numerous public statements made by Governor Cuomo indicating that the restrictions were specifically targeted at the Orthodox Jewish community. Three days after issuing the EO, for example, the Governor explained that it addresses “a predominantly ultra-Orthodox cluster,” and five days after that, he said the state was “having issues in the Orthodox Jewish community in New York, where because of their religious practices… we’re seeing a spread,” and that state-level enforcement was necessary because the “ultra-Orthodox communities… are also very politically powerful.”

Mr. Schick sees the ruling as expanding on prior precedents in the area of religious liberty. “This decision goes even beyond the landmark metzitzah b’peh ruling in the Central Rabbinical Congress case of a few years ago. That case involved a regulation that the court found was directed solely at religious practice. Here, we have the court applying strict scrutiny to a broad-based regulation covering religious and secular conduct. In other words, what was important was not simply that it singled out religion for restrictions, but that it disfavored religious conduct as compared to secular activity.”

Another important aspect of the Court of Appeals decision, notes Rabbi Zwiebel, is its finding that the court below erred in holding that Agudath Israel had not demonstrated irreparable harm because its congregants could “continue to observe their religion” with “modifications.” The Court of Appeals cited precedent holding that it is not for a court “to question the centrality of particular beliefs or practices to a faith, or the validity of particular litigants’ interpretations of those creeds.” And in any event, the court wrote, “Orthodox Jews are obligated to have an in-person Minyan — a quorum — before some of Judaism’s most sacred rituals. Orthodox Jews also desist from using electronics on Shabbat, so in-person gatherings are necessary for Agudath Israel’s congregants,” negating the possibility of a “Zoom minyan.”

Ultimately, what most strongly emerges from the one-two punch of the Supreme Court ruling followed soon after by the Second Circuit’s decision is the unequivocal endorsement of religious freedom by the highest tribunals of the country. As Rav Brudny puts it, “The Supreme Court is telling us that living by our mesorah of dor dor is a constitutional right and that’s a huge gift for Klal Yisrael.”

But Avi Schick adds that “after analyzing what the courts said in their rulings, it’s important to note what they did not say. The Second Circuit’s decision doesn’t say that safety and health precautions aren’t necessary, nor that the pandemic isn’t real and dangerous. This decision doesn’t say that social distancing isn’t necessary and appropriate, nor that masks aren’t required or that hand sanitizing isn’t helpful. The Court struck down attendance limits for houses of worship. But all the general health and safety rules remain in place.”

Rabbi Yisroel Reisman, who, along with the Agudath Israel of Madison where he serves as rav, were plaintiffs in these cases, says that this is just the latest in a string of legal victories in recent years vindicating the rights of religiously observant Jews: “The cases of the last few years — metzitzah b’peh, the substantial equivalency litigation — and now this case, were not easily won, but the Agudah had the courage to stand for religious liberty.”

Now that the issue has been settled conclusively in the courts, Shlomo Werdiger hopes that Agudath Israel can get back to its normal channels of advocacy. “Taking this approach was not our first resort and it certainly was not personal in any way. Now that the legal precedent has been set, we will continue to work productively and in good faith with people at all levels of government.”

Mr. Werdiger’s Agudah colleague, Rabbi Zwiebel, concurs: “We don’t like being in court with the governor or with government officials in general and we greatly prefer to resolve issues in face-to-face, behind-the-scenes discussion. We look forward with a spirit of goodwill to coming back to that.”

For his part, Avi Schick believes that with the evolution of societal standards and values, the frum community “needs to enhance its shtadlanus activities, figuring out ways to work within the existing political and legislative system to ensure that our rights and our communities are respected and protected. That means finding allies and making alliances, since we do better when we’re standing alongside others, although there may be times when we have to go it alone because of our particular values and interests. But our community’s approach should always be to attempt to work with broad coalitions. Litigation is only a last resort, when all else fails.”

Nevertheless, he believes these recent favorable legal rulings “make shtadlanus more likely, not less so, because until now government has been wont to say it’s our way or the highway, believing it has impunity to act in the realm of religion. Now they see that’s not the case and will be more willing to listen and negotiate.”

Schick points to another, more personal phenomenon he’s noticed: When Klal Yisrael proceeds with achdus, unusual success follows. “On the day before our Hoshana Rabbah court hearing,” he recalls, “as I sat in my office preparing, I called the Satmar Rebbe for a brachah. I couldn’t reach him, so I ran out to daven Minchah and eat a quick lunch in the Chabad Succah on Fifth Avenue. Just then, the Rebbe called to give me his brachah, and it occurred to me that this might be the first time someone sitting in a Chabad succah received a brachah from the Satmar Rebbe about a case on behalf of the Agudah.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 844)

Oops! We could not locate your form.