Significant Other

I’d like to hope that being sensitive to people different from themselves is in my children’s genes

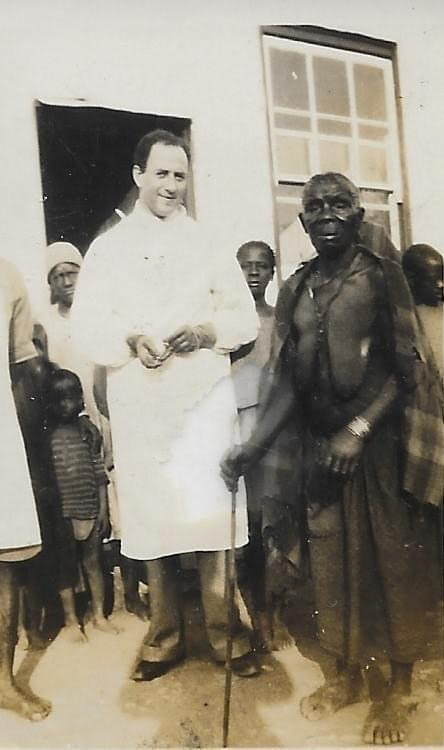

The picture of the man in the white coat is my maternal grandfather, and I am proud. Proud of his legacy, and proud that this image — of a man who served others, and “the other” — is ingrained in the consciousness of my children as well.

In the overwhelmingly wonder-bread world we inhabit, in which my children hardly see or interact with people of different skin color, this picture shows them a completely different reality. They have learned that the dark-skinned people in the picture were not simply patients of their great-grandfather, but rather a people whom he was devoted to serving. He cared about them family by family, individual by individual, during arguably the most extreme example of racial tension in the modern era: South African apartheid.

Dr. Henry Lazarus was an unsung hero who dedicated himself to healing the black population of South Africa at the height of apartheid. While he worked tirelessly after the war to help Jewish refugees, his own people, he was beloved by thousands of tribal Africans who traveled hundreds of miles from their villages to receive his treatment. Dr. Lazarus spoke four African languages fluently and was made an honorary member of the Royal Society of Witchdoctors (he was not a practicing member), upon which he was presented with a set of witch doctor bones and calabashes. If his patients did not have money, they paid in bananas or live chickens. He was affectionately known as Dr. Jabula, which means Dr. Happiness in Zulu.

I’d like to hope that being sensitive to people different from themselves is in my children’s genes, despite their limited exposure. I want them to always remember what their great-grandfather stood for as they try to make sense of the world around them, especially during these tumultuous times.

Historians and anthropologists can compare and contrast the experiences and dynamics of blacks in South Africa to those of blacks in the United States. But I’m interested less in the comparisons, and more in how my grandfather looked at people from such a radically different culture, who represented “the other” in a time of such significant social, political and economic divide, and made them his own. I am interested in how this figure of my past can inform the attitudes of my children’s present.

Looking askance at “the other” is something we frum Jews are familiar with. Historically, there’s good reason for it. We’ve been persecuted and oppressed, and assimilation is tragic. We need to vigorously protect our own.

Beside outside threats to our survival as a nation, we stringently guard our and our children’s personal connection to Yiddishkeit. We’re concerned about outside influences, sometimes even in the form of other Orthodox Jews. We are so steadfastly loyal to our hashkafos that those with different outlooks may harbor some sort of threat to who we are and what we believe. It’s “the other” shul, “the other” school, “the other” type. They’re different, and sometimes it’s hard to see past such differences when it comes to the things we feel so passionately about. Yet once someone or something is deemed “the other,” barriers are built up, even among our own.

If this experience exists in our own Orthodox communities among those who are relatively like-minded and similar looking, then the challenge is surely greater as we relate to those Jews of different racial ethnicities, and grows exponentially as we think about how we view gentile people of color.

While we have reason to keep to our own as Jews, to avoid social mingling and to protect the values we hold dear, the concern is when we view the other and their struggles as irrelevant, when in our quest to self-preserve, we forget our role to be a light unto the nations and instead funnel our light inward. We stop caring about the other and are concerned only with ourselves.

Prejudice, racism, and implicit bias are issues we need to grapple with as a community, comment by comment. Recent events have forced us to examine our personal beliefs about race and our views on racial tension and divide in this country. There’s history to be learned, research to be done, and lots of voices to be heard as we examine the facts and sift through the opinions all around us.

Where do we start? How do we ingrain sensitivity in ourselves and in our children toward those who are different from us? How do avoid othering and expand our circles of concern, while still maintaining our unique identities? Essentially, how do we become more sensitive to other human beings?

As with most important things in life, it starts at home. This is where the importance of discussion with our children is key. I’m thinking that our first step to combat prejudice and racism begins around our Shabbos table — after the divrei Torah, of course — where we sift through our feelings and thoughts, talk about history and current events, and examine any attitudes or biases that need some tweaking.

Our family has found that as we’ve been hunkering down at home these last few months, our Shabbos experience has gotten that much better. Our Shabbos table has been dominated lately by our teens asking questions and debating their personal views about current events. Teenagers and social distancing, of course, is a regular discussion each week, but lately they’ve added systemic racism, crime in the United States, white privilege, and the role of the police.

We as parents, of course, do not have all the answers — and frankly, some of the questions they raised are still tabbed “unresolved” in my mind. I often wish I knew more facts and details about the civil rights movement or crime statistics in our country. Yet the discussion itself is of great value.

Sometimes my children mention, with discomfort and frustration, jokes they’ve heard or words some people use to describe racial minorities. Yet I think about how they themselves have hardly had any exposure to individuals of different skin color, and sometimes I am not sure how that contributes to their views of “the other.” The question of the prevalence of racism in the Orthodox community is a hot topic. We discuss with our kids the importance of checking our implicit bias and thinking carefully how we may fall into the trap of stereotyping. Making jokes, or laughing at jokes, tends to erode our sensitivity to humanity. And as a nation that has experienced its fair share of discrimination, it behooves us to display sensitivity, even behind closed doors.

In addition to our Shabbos table talks, I’ve found it vital to read the brave accounts of our own black Jewish brothers and sisters, feel their pain, and take their experiences — and suggestions on how we as a community can cultivate more tolerance — to heart. We can learn so much about what to do right from their stories. They can be a training course in sensitivity for anyone open enough to face these issues head-on.

I don’t know exactly what specific traits my grandfather Dr. Lazarus, a.k.a. Dr. Jabula, possessed that enabled him to be such a selfless, sensitive healer to a people so different to his own. But I hope I inherited a little bit of those middos, and that my children did too. —

Alexandra Fleksher is an educator, a published writer on Jewish contemporary issues, and an

active member of her Jewish community in

Cleveland, Ohio.

Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 818.

Oops! We could not locate your form.

Comments (0)