The Real Deal

In 2020 we recognize “so normal” as authentic. That was Miri. No pretenses, no apologies, no straining

Years ago, you crossed paths. It may have been a brief encounter, it may have been a relationship spanning years. In that meeting place, something changed. Her hands warmed your essence, left an imprint upon your soul.

Seven writers sought out the women who changed them — and told them of the impact they’d had

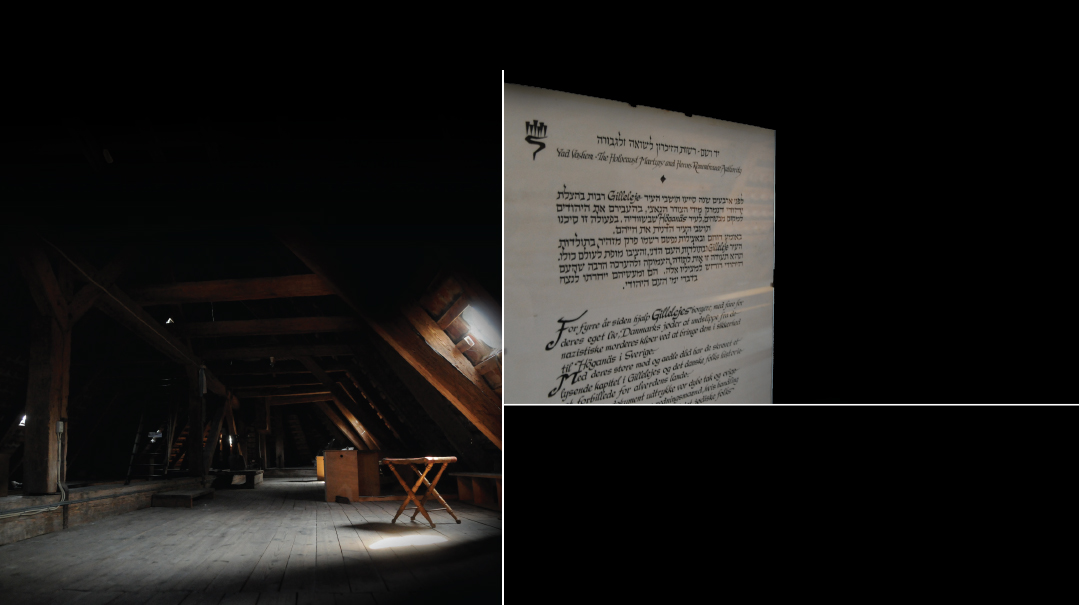

A lone spotlight shone as she made her entrance. She was radiant in white. If you’d look closely, you’d notice it was just a white graduation gown topped with a white fez sans tassel. But on her it was transformed and majestic. Her hands were raised, wide, accepting a heavenly embrace, and she danced down the stage steps while singing Mareh Kohein.

It wasn’t just the lighting. She was glowing. Her smile transcendent, her eyes closed in rapture. And through her effervescence, I felt it too. The beauty, the desire for Mashiach, the longing to witness mareh Kohein.

Did you just snort? I don’t blame you. It’s so saccharine, so cloyingly “inspirational.” Thing is though, I really felt it. When I witnessed her joy, I was with her, though I was a proud cynic. In her moment of transcendence, she transported me to a place I didn’t know was accessible to regular people.

*****

I’d just graduated eighth grade when I witnessed this Camp Bnos cantata. It’s a weird time for kids. You’re on the precipice, waiting to enter the next stage of life. You don’t know what will come, you just know everything will change.

People warn you. That the friends you have in elementary school rarely pass muster. There will be politics. There are so many teachers who barely know your name, classes are so much harder. But it’s also fun. And that’s for the regular kids.

For many, the road to high school isn’t straight. There’s rejection, conditional acceptance, meetings; even once acceptance is secured, the damage is done. The trauma seeds have been planted. The “I’m not good enough” shame too easily shifts to “I hate everyone and the system.” Guess which group I fell into.

In camp, between the end of an era and dreading what’s to come, it was hard not to look at the world with a jaundiced eye. Question every motive. Every value. And, at the same time, I tried to fit in, drink the Kool-Aid, because hey, everyone else loves it. The agony and ecstasy are common among teens and I was the teen-iest of teens.

And then Miri was my counselor. “Too frum,” I thought the first day. It was her clothes, billowy shirt with a safety pin between the top two buttons, Biz skirt, hair pulled back in a neat pony.

Later in the Social Hall we cheered for our group — Seniors. Because we’re best and better than the rest, and whatever terribly forced rhymes were in at the time. I never cheered, not my thing. I’d sit back and watch others stomp on bleachers and shout until their faces were red, temple veins bulging.

Counselors would cheer along with their bunk, but there was a certain restraint, they didn’t totally give way to the madness of the exercise. So there I was observing, jostled by those shrieking beside me, and my eye fell on my frummy counselor. She was cheering. Fist-pumping, voice-losing, bleachers-thumping cheering along with the bunk. She earned my respect, she was in this with her campers. And she couldn’t be that much of a frummy if she cheered like that.

But I soon learned my first judgment was spot on — she was a frummy. She was careful with her speech, she was super tzniyus, she knew halachah. But she was also “so normal.”

In 2020 we recognize “so normal” as authentic. That was Miri. No pretenses, no apologies, no straining. She always had safety pins on hand. She made brachos out loud. She smiled easily. Big smiles, with eye crinkles verifying their true intention. She had an ease about herself. I was too young to realize what I was witnessing and why I loved it, but she taught me I could have it all. That being frum and cool weren’t a contradiction, that being tzniyus didn’t mean I’d lose my voice and personality.

Watching her perform in the camp production, it was the first time I’d witnessed religious transcendence. I was cynical of any inspiration foisted upon me. Stories of miraculous tzaddikim, of mothers crying, of kids trying — I’d scoff. Especially when it came to Tishah B’Av; did these people really think I’d believe they felt something about the Churban, that they cried and yearned? But watching Miri perform… I’d never seen such intensity, such joy and longing.

I honestly can’t remember a single conversation we had. Although we had many over the summer. I remember sitting on her bed, me and my friends. But I don’t remember a single thing we spoke about. All I remember is laughing. A lot.

Oops! We could not locate your form.