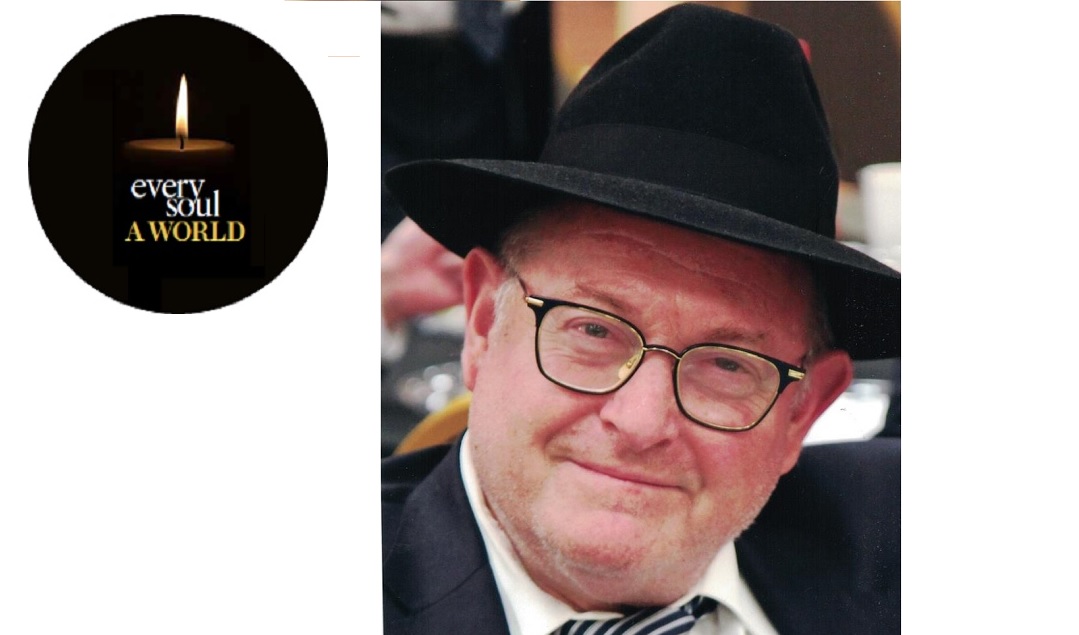

Mrs. Rochel Gluck

She was a successful craftswoman, businesswoman, and customer relations specialist — but she was always a mother first

W

hen the Gluck children would come home from school, they never headed for the front door. Instead, they would go around to the back of their Boro Park home and bend low to open the slanted, double doors of the basement. There they would be greeted by the warmth of their mother’s welcome and the heavenly aroma of her acclaimed baked goods.

In the 1970s, before it was usual for heimishe women to run their own business, Mrs. Rochel Gluck started baking as a labor of love, selling home-baked Yom Tov and simchah cakes to friends and family. After her husband suffered a life-threatening heart attack, her hobby turned into a full-time business and provided parnassah for her young family. Mrs. Gluck used only the best hashgachos and adhered to the highest standards of kashrus. This, coupled with her classic and iconic product, made for a winning combination. Through word of mouth, “Mrs. Gluck’s Cakes” became a simchah necessity and were sought after throughout Boro Park. Her specialty cakes included her famous Hungarian Nut Cake and her black-and-white checkerboard cake, and till today they are remembered with nostalgia.

Despite the heat of her kitchen, Mrs. Rochel Gluck could always be found neatly attired, sheitel in place and wearing her trademark deep-pink lipstick. She ran her business with minimal outside help, using a mental filing system that maintained everything — recipes, orders, and purchasing. For almost 40 years she kept all the balls in the air, working from early morning till late at night. Yet never a day went by in which she did not express how lucky she was and how much she loved her job. Mrs. Gluck was a true people person, and she shared sage advice and the gift of friendship with her customers. She was a successful craftswoman, businesswoman, and customer relations specialist — but she was always a mother first.

“My mother was ahead of her time when it came to child-rearing,” her daughter, Mrs. Sara Aszkenazy, attests. Before it became popular for educators and therapists to lecture about listening to your children and acknowledging their feelings, Mrs. Gluck was ahead of the curve. “We would never be scared to tell her if we did something wrong," her daughter, Mrs. Rivky Tessler, adds. "She was always understanding. When she went to PTA, she would be respectful and would listen, but she had the life-smarts to understand children. Her message was always clear, and the lesson was one of confidence. 'Everyone messes up sometimes, it doesn’t make you a bad person. You’ll do better next time.' "

Rochel Gluck did not learn the art of child-rearing from having enjoyed an idyllic youth. Though she came from a wonderful home, and always spoke about her mother's strengths and accomplishments, she only merited to live under her parents' roof for a brief part of her youth. She was number 9 of 11 children, and only 14 years old when her family was forced into a boxcar and shipped to Auschwitz. She would always recount the horrors of that journey, where in the stifling heat, she helped her mother care for her younger siblings. She held her two small brothers on her lap, as they clung to her in the scorching, airless car. Years later, when her children would complain of heat and thirst on a hot summer Tishah B’ Av, she would share with them the story of that fateful ride. When the doors of the boxcar finally opened, a pivotal selection was made. While Rochel held on to her brothers, her sisters were sent off to the right. Rochel, her mother, and younger siblings were sent to the left. A quick, intuitive reaction by her mother spared Rochel’s life when she pulled away her sons and shoved young Rochel toward her sisters on the life-saving line on the right.

Rochel never saw her parents and young siblings again, but she was fortunate to remain with her sisters, who cared for and protected her while they moved from work camp to work camp. They focused all their energies on survival and all but one sister, “her favorite one…” survived. The end of the war found Rochel alive but unconnected. She lived first in Paris, then Israel, and finally in the US, where she would marry and build a family.

Mrs. Gluck’s talented hands found expression in more than the kitchen. A competent and adept seamstress, Mrs. Gluck sewed her daughters' clothes. This kept expenses down, but more importantly, it imbued her daughters with confidence and made them feel special. “I was eight years older than my baby sister and I adored her! I took her with me everywhere,” her daughter, Mrs. Sara Askenazy, happily recalls. “I wanted everyone to know that we were sisters, so naturally that meant matching clothing.” Mrs. Gluck’s sewing machine worked overtime, and the Gluck children could always be identified by their matching outfits. “I remember when drop-waist dresses were in style,” shares Mrs. Rivky Tessler, that youngest Gluck daughter. “I admired them and by the next Shabbos I had four new drop-waist dresses.”

Mrs. Gluck doted on her middle child and only son Chaim or, as she referred to him, 'Chaim'l Sheina.' She always said he resembled one of her brothers. Chaim and his mother were cut from the same cloth, with similar character traits that always made them relate well to each other. Mrs. Gluck encouraged her son steadfastly when he launched his own retail business, utilizing the Gluck genes to run thriving bungalow colony groceries, and currently the Yagdil supermarket in South Fallsburg.

Mrs. Gluck's endless giving continued as her children became adults, married, and had families of their own. When Rivky Tessler and her family went to the Catskills for the summer, her husband joined her on Friday bearing gifts of soup, kugel, and assorted Shabbos delicacies, sent by her mother. “Honestly, I didn’t make my own soup for 30 years!” When she told her mother that her neighbor in the colony was feeling unwell, the following Friday included treats for her, too.

Though her greatest joy was to see her children happy, Mrs. Gluck did not spoil her children. Once, when the family was in the country for the summer, their father came up bearing an ominous letter. One of the children had not returned her library books before packing up for the summer and she had received a notice in the mail. “I thought they would put me in jail me from the way my father treated that penalty notice!” The Glucks paid the fee but the recalcitrant child was assigned chores around the house to earn money for the payment.

Sara Askenazy recalls how, on her birthday, which falls on Yom Kippur, her mother always made sure to mark the occasion. Despite the demands of the day Mrs. Gluck would take her to Thirteenth Avenue on Erev Yom Kippur to buy a birthday present. That love for a good Thirteenth Avenue shopping spree never abated and, after her retirement, Mrs. Gluck would take pleasure in her regular stroll down the avenue, walking from Fifty-second all the way down to Fortieth, perusing the shops, stopping for a slice of pizza, and hitting all the dollar stores to stock up on presents for her grandchildren.

Mrs. Gluck’s grandchildren adored her. “She was a kindred spirit. Always playing with them. Always with a prize or toy handy.” Aside from her children and grandchildren, Mrs. Gluck’s greatest joy was witnessing a hachnassas sefer Torah. Watching the parade of participants as a new Torah was brought home would bring her to tears. Haunted by memories of her youth, she considered the establishment of a new Torah as the Yidden's ultimate revenge.

Despite her difficult youth and the demands of her business, Mrs. Gluck made a happy life for herself. The contentment she achieved was not because she ran a successful business and had a long, loyal customer list. It was through the joy she brought to her husband, children, customers, and friends that made hers a fulfilled and satisfied life.

VIEW/DOWNLOAD PDF VERSION

Oops! We could not locate your form.