The Link

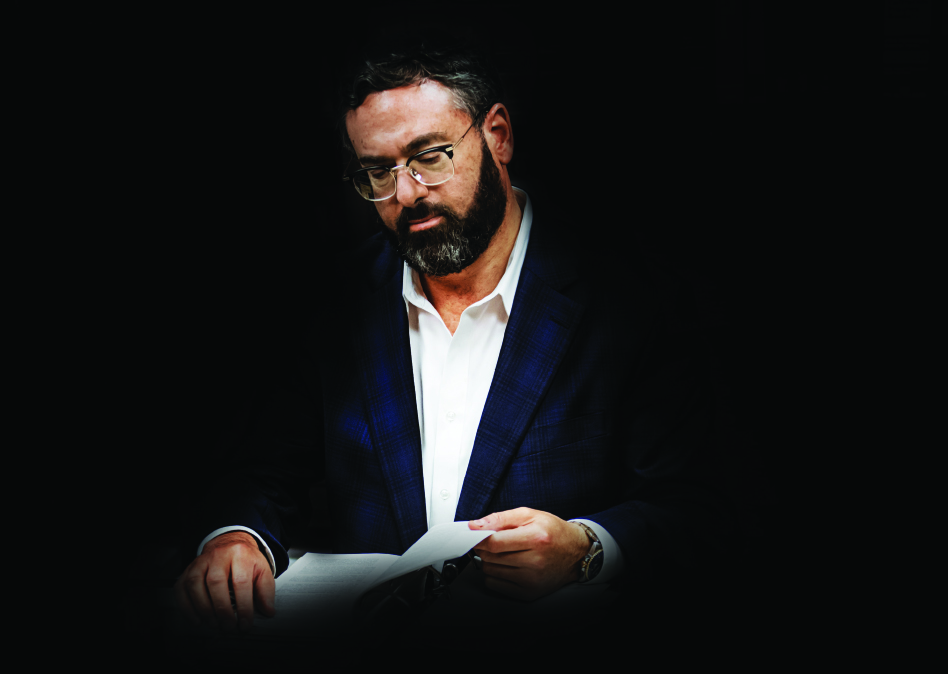

Montreal's Rav Pinchas Hirschprung was a pulsing link to the yeshivah and vision of Rav Meir Shapiro

I

n Montreal’s attractive Outremont neighborhood, a large park covers a full square block. I drive there and see snow dancing in the light, small piles of it sitting like cushions on the dark green benches, the water fountain peeking through a cap of white.

I park the car and walk down a winding path, a blanket of sparkling ice spreading before me, and the memories come, recollections of contentment mixed with awe.

Contentment, because is there anywhere safer for a child than next to his father, holding hands on a cracked sidewalk?

The awe was for the man we were about to see. We children of Montreal were raised to know what he was, what he represented. Every Yom Tov, my father, along with his friends and their children, would walk from the “uptown” neighborhood where we lived to the more chassidish “downtown” neighborhood. We were going to visit the Rav.

We knew that Rav Pinchas Hirschprung would greet each one of us with the same question: “Voss lernst du? What are you learning?”

Thinking back now, it’s a wonder that we felt no trauma, that we kids willingly joined these excursions. From my adult vantage point, I’d guess that it was because in Rav Hirschprung’s presence we were all equally awed — the learned adults became just like us children, for none of us knew very much in the presence of this gaon. We were all in the same boat.

The Rav knew every page in Shas, every line, every word, Bavli and Yerushalmi, Rashi and Tosafos, and he exuded that total command while half-lying on a burgundy couch in his living room, in a sweater.

I can use the word “thirst” to describe the way he inhaled words from the Gemara, but to be honest, I have never yet seen anyone drink as thirstily as Rav Hirschprung appeared, all day, every day. It was far more intense than thirst.

It’s now the eve of another Siyum HaShas; yet another chance to affirm the concept of uniting Jews through learning a shared blatt Gemara. The image of daf yomi’s founder, Rav Meir Shapiro, is part of the brand, ubiquitous on signs for local siyumim across the world.

But in Montreal, we can’t remember Rav Meir Shapiro without remembering Rav Hirschprung. Because the memory of the Lubliner Rav is bound up with memories of our city’s beloved rav, his preeminent talmid.

Those Yom Tov afternoons on the couch, Rav Hirschprung would speak of the birthday gift, the way he and a group of friends on the benches of Chachmei Lublin decided to celebrate the birthday of their beloved rebbi. Rav Meir Shapiro had no children; the ocean of love in his heart flowed toward his talmidim and the Torah they learned.

The talmidim came up with an idea: they divided up the entire Shas, every talmid taking ten blatt to master over the course of the day, and at sunset they all joined to make a Siyum HaShas in their rebbi’s honor.

On his rebbi’s yahrtzeit, Rav Hirschprung would speak about Rav Meir Shapiro and what he’d accomplished. He’d speak of the revolution his rebbi had created by establishing a genuine yeshivah in Poland, investing hundreds of budding scholars with dignity and respect.

And in true Galicianer fashion, speaking in his breathless way, he added flavor to the story. I remember hearing Rav Hirschprung discuss how once during the early years, his rebbi had noticed that one of the bochurim appeared near fainting on a Friday night: it turned out that the family where he was meant to eat that day had been too busy to feed him and he was fasting since the day before. Immediately, the Lubliner Rav made the decision to open a real yeshivah, with a dormitory and dining room, so that young bnei Torah could thrive. That dream would become Chachmei Lublin.

At this point in his retelling, Rav Hirschprung stopped, smiled gently, and remembered a story about the system of essen teig, where locals would feed the yeshivah bochurim.

Two bochurim, he said, were talking about the respective homes in which they were meant to eat.

“My host family only serves kasha, every single day, again and again, it’s always kasha,” the first bochur complained.

“I wish my family would give me kasha,” said the second, “instead, I get a teirutz: We just ran out, we forgot you were coming, the food got burnt.”

This too was Rav Hirschprung, master of kol haTorah kulah with the soft touch, blessed with the ability to quote lines of Tosefta and also share a delightful joke.

The balebatim of Montreal loved him, were as dedicated to him as to a father, and he connected with each one on his own level, offering them individual chances to learn with him b’chavrusa. But none was as close as the talmid who first encountered Rav Hirschprung in 1945, when the pride of Chachmei Lublin landed in a new world as a bereaved survivor searching for solace within the pages of the Gemara.

I take an elevator up to the fifth floor of a grand old building in the heart of Montreal’s downtown business core. P. Mandelcorn Furs has the feel of a different time: large, somewhat drafty rooms, creaky wooden floors, and at the end of a hallway, a spacious office.

Mr. Tzudyk Mandelcorn sits at a desk, the wall behind him covered in pictures — most featuring children and eineklach, though there are also a few politicians and some certificates. The most dominant picture, however, is directly behind his seat. It’s a picture of a couple, Rav Pinchas and Rebbetzin Chaya Hirschprung.

The man that Tzudyk Mandelcorn still refers to as “Rebbi.”

He was just a teenage student, a Canadian-born child of immigrants, in Montreal’s yeshivah, Mercaz HaTorah, when the gaon of Poland first walked into the classroom.

Back in Lublin, Rav Hirschprung had been the bochen, charged with testing applicants to Rav Meir Shapiro’s elite yeshivah. It was a test on 200 blatt by heart, and the tester himself, of course, had to be familiar with all of them. He’d written several seforim before turning 20, exchanging letters with the gedolei hador, including the Gerrer Rebbe. And now he sat facing a small group of Canadian boys, introducing himself as their new rebbi.

Mr. Mandelcorn smiles at a memory. “That itself is a story, how Rebbi got the job. Our regular rebbi, Rav Elya Chazan, had been offered a position in Torah Vodaath, and Rebbi was the temporary replacement. Why him?”

Rav Hirschprung had the same question: why would Rav Chazan, a talmid of the great yeshivos of Lita, give his job away to a Galicianer chassid?

“Rav Chazan said that he wasn’t sure if it would work out in New York,” Mr. Mandelcorn explains, “so he needed someone who would do his job well, but also give it back if necessary. He knew that Rebbi would give it up easily.”

Rav Chazan didn’t come back, though, and Rav Hirschprung became the maggid shiur at Mercaz HaTorah along with his role on Montreal’s Vaad Harabbanim.

“He would quote Rav Meir Shapiro, whom he referred to as ‘the Lubliner Rav,’ in shiur. I remember him telling us how Chachmei Lublin had sent out pushkes to homes across Poland, and askanim on behalf of Kupas Rabi Meir Baal Haness were upset. Until that point, they were the only ones who had pushkes, and they didn’t like the new initiative. They told Rav Meir Shapiro that was he was doing was halachically forbidden, so he asked his talmid — our Rebbi — for a mekor, a source that it wasn’t forbidden. Rebbi told us the mar’eh makom he’d found, but I don’t remember what it was.”

Montreal’s leading rabbinic body, the Vaad, had been around for decades. With the post-Holocaust influx of European immigrants, its culture began to change.

“It’s interesting,” Mr. Mandelcorn reflects, “how Rebbi was nearly always gentle and humble. He would give kavod to other rabbanim in his speeches, treating them with deference, and when we had to meet people for community matters, Rebbi would suggest that we go to their homes or offices rather than ask them to come to him. He never stood on ceremony. There was one area, however, in which Rebbi was firm and resolute: in matters of kashrus he didn’t show his softer side, and this was challenging for some people. That was part of the resistance to his rise through the Vaad Harabbanim and eventual appointment as rav harashi of the city.”

Tzudyk Mandelcorn was 21 years old, an unmarried college graduate working at his father’s business, when he got the call. “It was Rebbi, and he tells me, ‘Tzudyk, they closed the Bais Yaakov.’ ”

Montreal’s Bais Yaakov school had been running at a deficit for too long, and the teachers had walked off the job, leaving students scrambling.

“Ich vil es ibernemmen, I want to take it over,” Rav Hirschprung said.

“I was young, and I said, ‘Nu, zohl zein mit mazel,’ ” Mr. Mandelcorn recalls. “I wished him well.”

But the Rebbi wasn’t finished. “Tzudyk, you have good credit. Go to the bank and take out a loan so we can pay the teachers what they’re owed. We’ll get the school running again, and I’ll pay you back.”

Tzudyk Mandelcorn opened an account and formed a new board. Rabbi Pinchas Hirschprung became the school’s president, his 21-year-old talmid its secretary.

For close to half a century, they worked hand in hand: the Rebbi’s vision coupled with the talmid’s efficiency to create a world-class school.

“We were one of the first community schools, attracting students from chassidish homes along with students from homes that were very modern,” Mr. Mandelcorn says. “Rebbi was very proud of that. He felt that we have to be welcoming, that the school was for all Yidden. The only criterion was that the home had to be shomer Shabbos. That was it.”

There must have been some sort of clash between the rabbinic vision and administrative vision, I speculate.

Mr. Mandelcorn shakes his head emphatically. “No. He was the boss.”

In general, Rav Hirschprung approved of the school being fiscally responsible and always having money in the bank. “He felt that we could never know when the government might cut funding, or donors would be forced to cut back. He believed a school should be in the black.”

But one day, Mr. Mandelcorn recalls, there was some extra money in the school’s account. Rav Hirschprung called and suggested that the money be loaned to a particular individual who was in a tough spot. Tzudyk told the Rebbi that he didn’t think it was prudent to start lending out school money. A few days later, Rav Hirschprung mentioned it again, and the secretary reiterated his opinion.

“If Rebbi isn’t asking me, but telling me, then of course there’s no discussion,” Reb Tzudyk added.

Two more days passed, then Rav Hirschprung said, “Tzudyk, zolst machen a check, please write a check.”

Rav Hirschprung generally left personnel decisions to the chinuch staff.

“Rebbi admired our principal, Rabbi Shneur Aisenstark, and trusted him completely. Rebbi told me more than once that he appreciated the fact that Rabbi Aisenstark didn’t automatically fire people who weren’t producing, that he found ways to make them productive, or new roles in which they could contribute.”

The rav worked to raise funds for Bais Yaakov throughout the year, getting personally involved in soliciting honorees for the annual dinner — a fact that makes the next story all the more remarkable.

“Someone close to Rebbi passed away and left all his money to tzedakah. He named Rebbi as the executor, awarding him the authority to select the beneficiaries. Rebbi called in a talmid and had him draw up a list of the various city mosdos, then he divided the money, a respectable sum, between them — leaving out one.”

“Rebbi, how come none of the money goes to Bais Yaakov?” asked the perturbed talmid.

“Because people know I’m partial to the mosad, that it’s close to my heart,” Rav Hirschprung explained. “It’s negius. A rav can’t pasken that way.”

Even as the community migrated west and most of the Rav Hirschprung’s talmidim settled uptown, his residence remained on Querbes Street, in the chassidish community.

“This was on purpose,” Mr. Mandelcorn explains. “Rebbi wanted to learn — sitting by a Gemara was his oxygen — and he knew that if he moved uptown, people would be coming in and out of his house all day. He liked the relative peace of downtown.”

Devoted talmidim, eager to remain connected to Rebbi even though they no longer lived in close proximity, opened a shul uptown and named it Minchas Soles, in tribute to the sefer written by Rebbi’s beloved grandfather, Rav Dovid Tzvi Zehman.

Rav Hirschprung would come uptown for Shabbos Hagadol and Shabbos Shuvah to give the derashah in that shul. When he and his rebbetzin came for Shabbos, they stayed with the Mandelcorns. “But he asked me not invite an oilem for dessert, even though so many people wanted to come by. He said to me, ‘Tzudyk, I don’t want to fihr tish!’ ”

He would also join his talmidim for the Yomim Noraim, and serve as makri for his beloved talmid, who was the baal tokeia.

“When we started the minyan, I asked Rebbi whether to do the shevarim and teruah with one breath or two. He looked at me and told me to continue doing whatever I had done in my old minyan. He had such humility. It was only when he saw that I desperately wanted his psak that he told me what he preferred — that I do it b’neshimah achas, in one breath.”

The veteran baal tokeia would place his watch on the bimah before starting to blow: one year he forgot, and the makri, radiant countenance partially hidden by his tallis, leaned over.

“Tzudyk,” he whispered, “dein zeiger. Your watch.”

“That was Rebbi’s mix,” the baal tokeia reflects now, “the holiness and the pragmatism.”

Reb Tzudyk Mandelcorn had a steady learning session with his rebbi after work. In addition, they spoke on the phone every day — even if one of them was traveling.

As the Rebbi got older, the talmid would encourage him to go out for a daily walk. “He enjoyed it, and it was important for his health. One day during our walk, I saw that the Rebbi’s spirits were down. He wasn’t feeling well and it was affecting him.”

“Does Rebbi remember the melamed named Brenner?” Reb Tzudyk suddenly asked, referencing a long-ago Montreal resident, a Galicianer talmid chacham.

“Yes, sure.” Rabbi Hirschprung smiled at the memory. “He was full of Torah, and also an ish emes.”

Reb Tzudyk walked a few more steps, then said, “Well, he once told me that Rebbi would have been an ‘item’ 300 years ago, respected among the gedolim.”

Rav Hirschprung reacted with astonishment. “Voss heist, how can you say that? In the dor of the Taz?” He looked at his talmid incredulously.

They walked a bit more, then Reb Tzudyk said, “The Rebbi just said Brenner was an ish emes, he spoke truth.”

It was quiet after that, but the talmid saw that he’d restored the Rebbi’s spirits — not with the compliment, but with the reminder of the glory and joy of the Torah world and his place within it.

Someone once asked Rav Hirschprung where he lived. “Bavel,” the Montrealer Rav replied, “I live in Bavel.”

On that day, his talmid reminded him of this reality.

Throughout our conversation, Mr. Mandelcorn speaks in even tones, his expression and voice concealing his emotion. But then he stands up and removes a paper from a cabinet in the corner. He places it before me, without a word.

At one point Rav Hirschprung underwent a serious operation, and in the hospital, he gave his talmid a handwritten letter.

He did not know how the surgery would go, he wrote, and in the event that he wouldn’t pull through, he was leaving all decisions regarding his beloved school to his talmid.

Hakoach shehayah li, yihyeh lecha…whatever power I held, you will hold….

A few years later, when Rav Hirschprung was in the throes of his final illness, he turned to the talmid who was never far from his bedside and said, “Remember my letter.”

For the first time, Reb Tzudyk Mandelcorn’s voice cracks.

“Think about this, this man whose entire vitality came from the Torah itself, who lived in a dimension of pure Torah, a tzaddik — the Belzer Rebbe once told me, ‘My chassidim only know about the gaonus of your rebbi, but they don’t even see his pure yiras Shamayim’ — a sensitive, compassionate man, and he’s writing, ‘Maybe I won’t be found worthy of a refuah.’ ”

Reb Tzudyk says it again, in wonder. “Maybe I won’t be found worthy...”

Then he looks at me. “That’s what makes me cry. That sort of greatness with that sort of humility.”

Like the story the Rebbi often told of meeting Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski in Vilna. Rav Chaim Ozer spoke in learning with the boy from Dukla, quoting a gemara in Bava Basra 87. The young Pinchas Hirschprung suggested that it was on daf 88. They argued about this, until Rav Hirschprung said he would go find a Gemara so they could see the truth.

Rav Chaim Ozer grabbed hold of his own beard, and asked, “Do you want to shame this white beard?”

Rav Hirschprung didn’t get the Gemara, but later on, he went to check.

He’d been wrong.

Rav Chaim Ozer had been right.

And Rav Chaim Ozer had known that he was right, and he’d wanted to protect the dignity and honor of the young talmid chacham.

The story, Rav Hirschprung would say, wasn’t about the great genius of Rav Chaim Ozer, nor about his modesty — but about the way they both lived together in one person, each trait complementing the other. The humility is that much more valuable against the genius, the genius so much more impressive against the humility.

Maybe, Rav Pinchas Hirschprung wrote, maybe I won’t be found worthy….

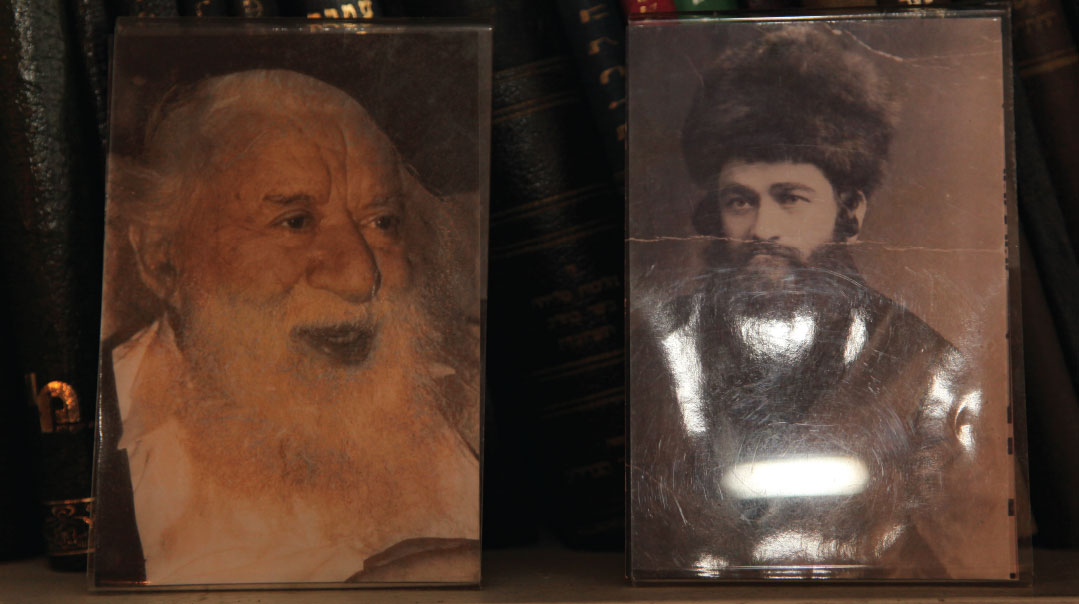

Several months after Rav Hirschprung’s passing, I went to the house on Querbes Street.

A great talmid chacham was visiting from Eretz Yisrael, someone who considered himself a talmid of Rav Hirschprung. He asked me to take him over to the Hirschprung home so he could be menachem avel.

I drove him, of course, but I was perplexed: shivah was long over.

“The Rambam is mashma that there is a din aveilus on the house itself,” the talmid chacham told me, reverting to the language of perfect truth, the world of diyukim creating reality, the world of Rav Hirschprung.

He wanted to sit in the room and mourn.

I took him inside and looked around. And even I could sense that the room felt orphaned — its storied occupant gone but the impossible towers of seforim still in place, the cushions on the couch faded from years of being singed by holy fire.

The pictures were untouched, and in the silence, I observed the picture of the Lubliner Rav that Rav Hirschprung had always kept near him. And I noticed something: the likeness of Rav Meir Shapiro was realistic, but the color of the paint was not. Along with the folds of a tallis and a sefer Torah in the Rav’s hand, the artist had painted the Rav’s coat a deep, unlikely blue.

The paint colors aren’t realistic? Well, neither is the story.

The Lubliner Rav didn’t leave over generations. The building he erected with such sacrifice has become a nursing school. The majority of his talmidim were murdered.

Yet the sefer Torah in his hands lives, and an army has come forth to accept it once again. As unlikely as it seems, he is still here, his final cry of “nohr b’simchah” still reverberating.

In Rav Hirschprung’s house you feel it: Rav Meir, still lighting up the way ahead.

(Originally featured in 'One Day Closer', Special Supplement, Chanuka/Siyum HaShas 5780)

Oops! We could not locate your form.