Off-Duty

| May 2, 2018Lieutenant Colonel Mordaunt Cohen, the oldest and highest-ranking British Jewish officer to serve in World War II still alive, will be 102 this summer

(Photos: Mendel Photography)

Lieutenant Colonel Mordaunt Cohen, the oldest and highest-ranking British Jewish officer to serve in World War II still alive, will be 102 this summer, but he’s still a soldier at heart — patriotic, confident, and humble — as he recounts in vivid detail how he kept mitzvos in the trenches of Nigeria and Burma. That fighting spirit has even earned him a place on the Queen’s 2018 honors list for educating a public decades removed from the horrors of war.

W

hen World War II ended in Europe in May of 1945, not every Allied troop could throw up his hat in celebration. British Lieutenant Colonel Mordaunt Cohen, an Orthodox Jew who kept mitzvos even as he’d been dispatched to the ends of the earth, had been sent to Burma via Bombay where “we felt we were part of the forgotten war, out there in the bush. Everyone was at home celebrating, and we were still out there fighting in conditions you can’t imagine.”

Cohen, who will turn 102 this summer, has no regrets, though. The war had taken him from the close-knit Jewish community in the northern British town of Sunderland where he grew up, to bustling Indian cities and commanding Muslim troops, first in Nigeria and later in Burma. Over seven decades have passed since then, but Mordaunt Cohen is still every bit the soldier: patriotic, confident, humble, kind, and brave.

As the highest-ranking veteran of World War II service in Burma and Britain’s highest-ranking Jewish World War II veteran as well, the lieutenant colonel’s colorful life and incredible memory for detail has fascinated many audiences over the years, both within England’s Jewish community and in schools around the country. So it really wasn’t a shock when his name was included on the Queen’s 2018 New Year’s honors list, making him an MBE (Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire) for his services to Second World War education.

Doing My Part

Mordaunt Cohen was born on August 6, 1916, to Israel and Sophie Cohen in Sunderland, about 13 miles from Gateshead. While there’s no longer an Orthodox community in Sunderland, in its heyday the British industrial port town hosted a close-knit, convivial community, with two shuls and exacting halachic standards. Since a core contingent of the Sunderland community had emigrated as a group from the town of Kretinga in Lithuania, the town’s Jews maintained a staunchly Litvish character.

Mordaunt’s maternal grandfather Reb Chatze Cohen (both his father and mother had the last name Cohen, and so did his future wife), emigrated to England in 1888 with 14 children and was one of those Lithuanian immigrants.

“Zeide had semichah, but he never used it. He was always affectionately known as Reb Chatza. His position in Kretinga was something like town clerk,” says Cohen, whose lilting articulation belie his age, while his soft accent, more musical than the more popular London twang, confirms his Northern British origins.

Mordaunt’s mother was raised in Reb Chatze’s Yiddish-speaking home, and his own cheder education was also in Yiddish. “We went to cheder after school, for about 16 hours a week, and we learned to translate the Chumash, Tanach, Rashi, Shulchan Aruch, and Gemara all into Yiddish.” He’s proud of the bar mitzvah pilpul he gave in Yiddish. “It wasn’t written down and I had to learn it by heart from my rebbi.”

Cohen’s father, who had emigrated from Lithuania at age three, had been raised by his widowed mother, Mordaunt’s Bobba Raiza, in Glasgow, Scotland. Originally a traveling peddler, he built up a prosperous business as a wholesaler of fancy goods in Sunderland, so that Mordaunt’s childhood was comfortable.

After attending a top local high school as a scholarship student, Mordaunt was articled to a legal practice. In those days, this was equivalent to attending university. In 1938, he was just 21 when, having received a thorough grounding in all areas of British law, he sailed through his final exams and qualified as a lawyer, and opened his own private practice.

Athletic and strong, sports and running were also part of his life, and Mordaunt belonged to two cricket teams, although he never played on Shabbos.

“I kept up football [soccer] until my thirties, cricket until my forties, and when I felt I couldn’t time the ball right anymore, I took up bowling to keep fit,” he says.

In the 1930s, members of the Sunderland Judeans Club to which he belonged participated in a first-aid course, and Mordaunt qualified as an ambulance medic; when England entered the war on September 3, 1939, he was enlisted by the local civil defense to take charge of a first-aid station.

For some, this would have been enough of a contribution to the war effort, but Mordaunt felt he could do much more. There was a Jewish refugee hostel for girls nearby, who were brought over on a Kindertransport; and while no one could fathom what horrors were to come, he’d heard what was happening in Germany and felt he couldn’t ignore it.

“As a Jew,” he says, “I wanted to be in there doing my bit for my country and my people against the German enemy.”

And so, Mordaunt closed his legal practice and volunteered for service in December 1939, becoming one of about 60,000 Jewish soldiers who served in the British army during WWII — including approximately 10,000 German and Austrian-Jewish refugees. His first posting was as an observation post gunner, and the accommodations were spartan. “My bed was two wooden planks 18 inches wide, with a pallet that we filled with straw from the stables.”

But at least he was close to home. “I was about 40 miles from my home, so Mother used to send me parcels of chicken every week. I didn’t eat any of the army meat or chazerai,” he recalls.

Within a year, the young soldier had three stripes and had attained the rank of lance-sergeant. In 1941, Mordaunt was recommended for a commission and took part in officer cadet training.

“When I got there, there were 30 cadets in the room. The officer called the roll, and when he got to Cohen, two of us stood up. Thirty cadets, and two Cohens! Albert Cohen was also a lawyer — and also a very good cricketer. He captained the cadets’ cricket team, and I the athletics team — and we fasted Yom Kippur together.”

By that time, all of mainland Europe had fallen to the Nazis, and German bombers were pounding Britain’s urban and industrial centers, and the tension was high: Would the unbeaten German army reach England, thus taking all of Europe prisoner?

Lieutenant Colonel Cohen’s first posting as officer meant going back again to the north of England, commanding an anti-aircraft regiment that protected the targeted port, shipyards, and iron works of Sunderland. This was much riskier business than the previous posting, but Cohen says he dealt with the real fear of war the same way everyone else did.

“If anyone tells you that they weren’t afraid in action, they’re not telling the truth. When you go into action the first time, sure you’re scared. Bombs are dropping all around you. But with time, you overcome the fear. You take it as it comes along. The German bombers would generally come over between 2 and 3 a.m. so our nights were full of action.” Mordaunt learned to get out of bed, into uniform, and be at his command post within two minutes.

In the end, though, he wouldn’t be going to the front to fight the German enemy. Instead, Mordaunt was being shipped off to Africa, although he wasn’t officially told of the destination until they were out in the middle of the ocean. He assumed he was headed for the Middle East.

Mordaunt’s ship — a requisitioned pleasure cruise ship — featured a vast ballroom that was converted into sleeping space for 360 officers. There were three tiers of beds, and he had been assigned a top bunk. “That was lucky, because it had an extra three inches,” he adds. But then another officer came up. “Excuse me,” the second officer said, “I think you’ve taken my bunk.” Sure enough, he was also called Cohen. The two young Jews became friendly, and Mordaunt’s new friend said that he had been on leave in England and was going back to his regiment in Nigeria. Aha, now Mordaunt knew where he was headed: Africa.

Another companion on the boat was a Jewish physician from London named Dr. Bernard Homa, who was to serve as deputy medical director. He and Mordaunt took their meals together on the ship — and then would sit down to learn some Torah.

In Lagos, Nigeria’s largest city, Cohen became one of the few Jewish officers to command Muslim troops as part of the Royal West African Frontier Force. He was the only Jew in his brigade, responsible for a small cadre of British officers and NCOs and a large group of Nigerian Muslim volunteers. Nigeria was part of the British Empire then, and many locals were enthusiastic about serving as British soldiers.

The main obstacle was the language barrier, and orders were that British officers were to learn Hausa, the local language. But Cohen wasn’t convinced that this made sense. “I told my superiors, ‘This is draft. We’re going to serve in war together with these people. If we get bumped off and they send out reinforcement officers from England who don’t speak a word of Hausa, they won’t be able to communicate with the local soldiers.’ ”

In the end, two officers in the troop — schoolteachers by profession — taught the Nigerians some rudimentary English. Then it was Cohen’s job to teach them how to use the anti-aircraft guns, predictor, height finder, and radar instruments. “They became very proficient, which was important because I had to trust them with my guns. I would converse with them about Oba Ibrahim [Avraham Avinu]. They didn’t know what a Jew was, so they called me the White Muslim.”

Cohen’s professional background turned out to be an advantage as well. “I was admitted to the Nigerian Bar, so I could represent my soldiers in court if they got into trouble with the local civil authority,” he says.

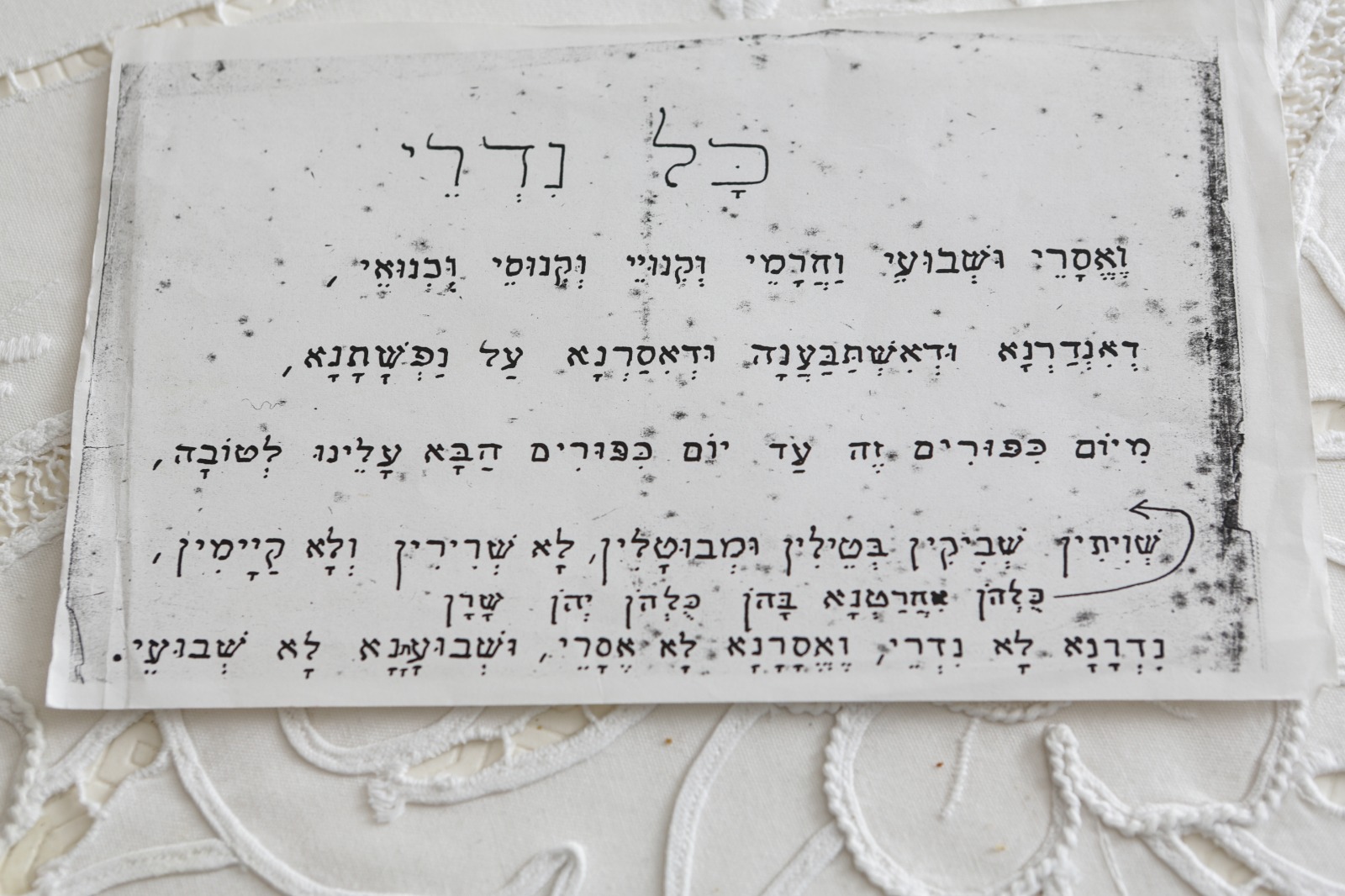

On weekends off, Cohen traveled around the vast country, spending some time with his friend Major Dr. Homa. Together they obtained leave for all Jewish servicemen for Yom Kippur and organized services for them. They sent off to England for machzorim, but the ship carrying them to Africa was torpedoed. With no alternative, Bernard and Mordaunt sat down to write up Kol Nidrei from memory. “Years later, when we compared ours with the original, there were only three errors,” he says with a touch of pride. (The handwritten Kol Nidrei is now in the Jewish Military Museum in London, together with Mordaunt’s army uniform.)

Pesach was also plagued by the realities of war. Dr Homa and Mordaunt wrote to the Board of Deputies in Johannesburg to ask for a shipment of matzah, wine, and Haggados. It came a week after Pesach.

In 1943, after a year in Nigeria, Mordaunt’s regiment was told that they would be transferring from Nigeria to Burma — now known as Myanmar — in order to fight occupying Japanese forces, who in 1941 had bombed their way into that Southeast Asian country.

In preparation, all leaves were stopped, but Mordaunt recalls one exception. “I had one very good Nigerian sergeant, an old fellow who served in East Africa. He came to me and said he wanted to go on leave. ‘Want to go to my village to get Juju charm.’ I asked how long it would take. He said, ‘Three days to village, one day there, three days back.’ I gave him permission, because I knew I could trust him. When he came back, he said, ‘Sir, you like see ’em Juju?’ I said yes, and he showed me a pouch which was wound around his arm and neck, with verses from the Koran in it. It turns out the Juju charm was their version of tefillin.”

On the way to Burma, they ended up in Bombay, traversing India by slow-moving local trains — five days to Calcutta, then by ship from Calcutta to Chittagong, and more local trains up-country to the northeast Indian state of Assam, where the Japanese army were advancing.

The Fourteenth Army, which defended India and retook Burma from the Japanese, is nicknamed the “Forgotten Army” because its operations received little attention. Even at the time, the media focused mainly on the war in Europe. “We were out in the bush, with no radio, no newspapers, little communication. We really didn’t know what was going on with the war in the rest of the world.”

Conditions, Cohen remembers, were harsh. “It wasn’t only the Japanese we had to contend with. It was the climate and the brutal tropical diseases.” In Nigeria, the British troops took quinine and anti-malaria drugs. When Mordaunt Cohen’s regiment reached India, they were told they no longer needed anti-malaria precautions — but soon after, Cohen was hospitalized with malaria, followed by acute infective hepatitis. He was given leave to recuperate in a Jewish boarding house in Bombay.

Through a Jewish chaplain, he was invited to spend Pesach of 1944 with Sir David and Lady Ezra, the leading Jewish family of Calcutta. “I traveled by road, by steamer, by rail, and arrived the night before Pesach. Their home was a mansion — it even had its own private zoo,” he says. “Lady Ezra, who was a Sasoon, was known to the natives as the Burra Memsahib, which means the Big White Lady. I was shown into the drawing room, where there was a short man with a yarmulke holding a feather and candle.” It was bedikas chometz, and the aristocratic Sir David was doing it himself. Seder night followed, with around 20 British and American Jewish servicemen around the table.

On Yom Tov morning, Mordaunt went to shul, but was disappointed: An American chaplain who was a Reform clergyman conducted the services. He hadn’t thought to include Mussaf, but allowed the religious British boys to conduct it. “Then he told us, ‘If you fellows want, you can conduct the whole service tomorrow,’ which we did. And as we were leaving, he asked us, ‘Anybody want a lift?’”

Pesach was a special reprieve, but the following Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, no one got leave. The Japanese guns were pounding full force.

Mordaunt Cohen’s last wartime posting was as staff captain of the brigade’s headquarters in Shillong, the capital of Assam, where about 6,000 soldiers were stationed. As well as servicemen, refugees from Hitler had also found their way to remote corners of northeast India. He remembers a kind Jewish family there, a German refugee family by name of Traub. “The husband, Dr. Traub, was a dentist. I visited them when I had leave, and I also got free dental treatment.”

The German surrender on May 8, 1945, and the end of the war in Europe meant nothing to the Japanese, whose guns continued to pound the Royal West African Regiments’ positions in Burma for another three months. On Mordaunt’s birthday, August 6, 1945, the atom bomb on Hiroshima ended the war in the East.

Mordaunt finally headed home in December of 1945, and after being demobilized a few months later, took up the busy reins of civilian life again. He reopened his legal practice and threw himself into Jewish communal work as well, becoming president of the Sunderland Hebrew Congregation, as well as chairman of the Association of Jewish Ex-Servicemen. “I haven’t missed a Veteran’s Day parade in 60 years,” he says, noting that he heeded the call of the hour and enlisted in the Territorial Army, where he soon rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

A few years later, in Manchester for a legal consultation, Mordaunt met an unforgettable young lady — Myrella Cohen. Myrella was a fine Orthodox girl — and a university graduate and barrister.

“Not too many women were at the bar at that time,” Mordaunt says. “One of the leaders of the Manchester community had met Myrella when she was studying law at university, and said to her, ‘Go home, get married, raise a family, and leave the law to men.’ That only made her more determined.” Mordaunt and Myrella were on the same page, though — they both thought that she could work as a lawyer and raise a family, too. They were engaged on Purim 1953 and, Mordaunt notes of his wife of nearly half a century, she didn’t even have to change her name.

When Mordaunt and Myrella married and set up their home in Sunderland, the new Mrs. Cohen joined the chambers in nearby Newcastle. She was the only female barrister there, and amid plenty of raised eyebrows, passionate and highly intelligent Myrella built up a successful practice while raising the couple’s two children. In 1970, her career took a major leap when she was appointed Queen’s Counsel — a selective title for top-tier barristers. And in 1972, Judge Myrella Cohen became the first woman judge in Northeastern England — and the youngest and third female judge in all of England. With a mixture of toughness, compassion, and sharp wit, she presided over numerous criminal cases, yet her colleagues knew that Friday afternoons off were non-negotiable. On the drive home from Newcastle, Myrella would stop off at Stenhouse’s bakery in Gateshead to buy kosher bread for the week.

Two years later, a letter arrived in Sunderland from the Lord Chancellor’s office. (The Lord Chancellor in Britain is the highest ranking of the officers of state, a member of the Cabinet, and Secretary of State for Justice.) Mordaunt Cohen had been recommended for the full-time position of Chairman of Industrial Tribunals. At his interview in the imposing chambers in London, he made it clear that he did not work on Jewish holidays.

“The Lord Chancellor said that it didn’t matter, that I could take off those days in addition to my annual leave, but I didn’t want to take advantage of that,” he says. Mordaunt and Myrella Cohen of Sunderland were the first couple in England to be chosen for full-time judicial appointments.

Soon afterward, Myrella was attending a judicial function in London when the newly-elected Lord Chancellor came up and introduced himself. He said to her, “When your husband was elected as Chairman of Industrial Tribunals, there was a lot of opposition within the Ministry of Justice. People felt that too much judicial power would be in the hands of one family. But I didn’t agree with them. I didn’t see why a good man should be held back because of his wife.” In fact, it was Judge Myrella Cohen who drafted the British legislation that works to solve the issue of agunos, as well as a halachic prenuptial agreement that is used by the London Beth Din to this day.

Mordaunt says he didn’t mind retiring from private practice when he assumed a judicial role. “Actually, it was wonderful not having to worry about clients and staff and cash flow or being woken up in the middle of the night by the police saying, ‘We’ve got Jack Smith here, he’s asking for you.’ ”

By the time Mordaunt retired in 1989, the once-thriving Sunderland community was in decline, and the Cohens moved to London to be near their daughter Sheila. Sheila’s husband, Stuart Taylor, is a former vice president and chief executive of the United Synagogue, Britain’s largest Orthodox synagogue movement.

“I’ve got my own beis din,” says Cohen, a proud Jewish grandfather of three rabbis. One grandson is the regional director of NCSY in New England, another is associate rabbi of Young Israel in Century City, and a third is a rabbi at Western Marble Arch synagogue in London. Another grandson, Saul Taylor, is a trustee of the United Synagogue, and a fifth grandson, Jeffery, is an actuary living in Raanana, Israel.

After a 27-year battle with cancer, Myrella Cohen passed away in 2002. She fought her illness with great bravery, continuing with life and work so that most people did not even know she was unwell.

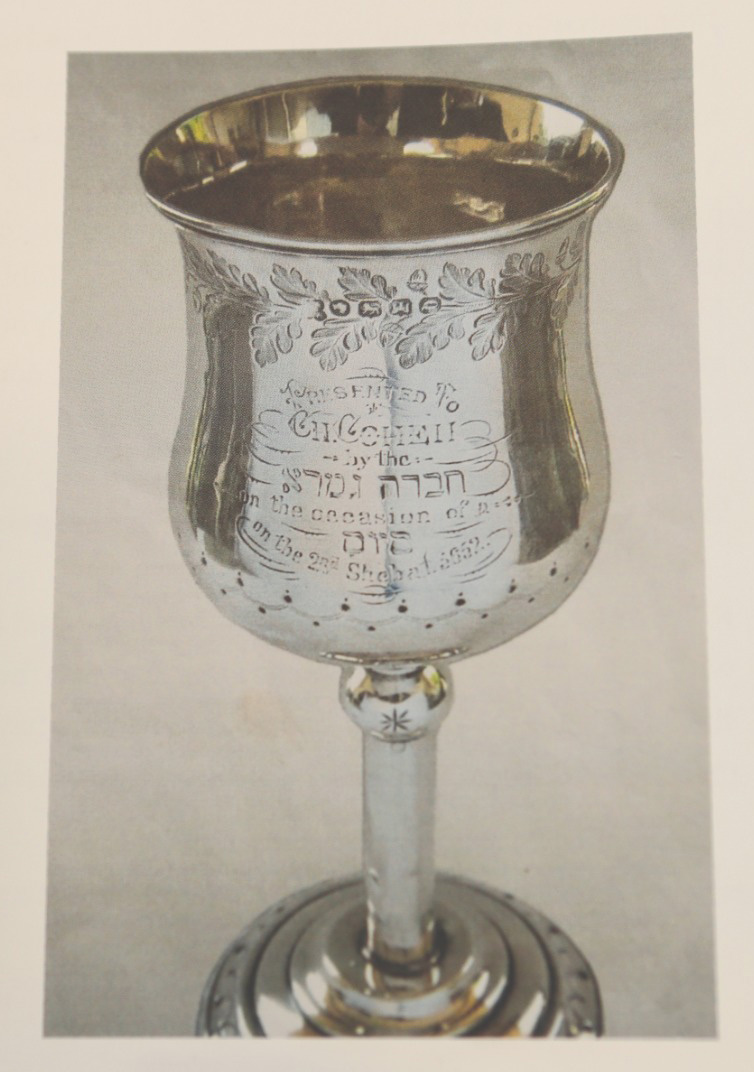

Today, in his tasteful ground-floor apartment in the thriving community of Edgware, in Greater London, Lieutenant Colonel Mordaunt Cohen, MBE, sits among a century of memories — the walls are full of family pictures and mementos of his distinguished judicial career. Proud of his family roots and hopeful about the future, Cohen believes that they are connected. “We have to remember our roots in order to preserve them for the family’s future,” he says, showing a silver becher that was presented to his grandfather Reb Chatze Cohen by the daf yomi shiur he lead in Sunderland 125 years ago. From the frames on the wall, the smiling pictures of grandchildren seem to agree.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 708)

Oops! We could not locate your form.