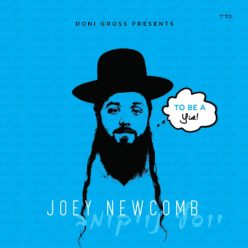

Joey (Yosef) Newcomb, a rising star of the kumzitz and inspirational concert circuit, says that his trademark guitar notwithstanding, he never actually took music lessons. “But as a teenager, I attended yeshivah Shaarei Arazim in Monsey [a niche yeshivah for different types of bochurim focusing on and building their individual strengths] and over there it was like everyone played guitar. I picked up a lot from them.” Enough, apparently to play his own accompaniment on his debut album To Be a Yid — which feels a bit like its own multi-track kumzitz.

At home, Abie Rotenberg’s Journeys albums and Shlomo Carlebach’s music were the dominant musical influences. Later, Rabbi Shmuel Brazil also shaped Joey’s view on the power of music during Melaveh Malkah kumzitzes in yeshivah.

“Until today,” says Joey, “I’m a big follower of Abie. There is so much depth in his music — and collaborating on music or singing with him is my musical fantasy. I got some warm feedback from him on the song ‘It’s Never Too Late.’ ”

The Breslov-inspired “It’s Never Too Late” was written by Joey during some moments of introspection (“It’s never too late to correct your mistakes because we know ein shum yei’ush b’olam klal…”). “I wasn’t feeling too happy with myself or the spiritual place I was in, and the niggun just came to me. I think that low feeling worked its way into the song and that’s why people can connect with it. It’s not about, ‘Oh, I didn’t know you went OTD and came back on, Joey!’ but it’s about the reality that every Jew can stumble and slip — and he can always return too.”

Joey was “discovered” by producer Doni Gross, during the time he was learning in kollel in Far Rockaway. After he played and sang at a Chanukah mesibah, fellow avreich Yitzy Gross, Doni’s brother, asked him to perform at a sheva brachos his in-laws were making. “I came along with my guitar, and somehow everyone was singing and dancing until three in the morning,” he recalls. The next day, Yitzy’s mother, Mrs. Gross, called to hire Joey for another sheva brachos. Before he knew it, his calendar started to fill up with events — and Doni Gross had caught his brother’s and mother’s enthusiasm. When Joey’s performing, it’s not about playing background music, but about connecting with the crowd. A born teacher, he’ll intersperse tzaddikim stories and divrei Torah too. “It’s not a successful evening for me unless the people are dancing or gathered around to share some Torah,” he says.

But although Joey was busy playing and singing at one event after another, when it came to writing music, he felt blocked. “For years, I’d been trying to compose but it just never worked. So I figured, you either you have it or you don’t have it, and I’d better just stick to playing acoustic guitar and singing.”

In the back of his mind, though, he never gave up on channeling inspiration into original music. Then, around two years ago, while Joey was sitting at the table one Motzaei Shabbos eating Melaveh Malkah, the niggun for what would become his popular “Borei Pri Ha’etz” came to him. A while later he added the words — which are essentially the brachos we say — because he wanted to create a vehicle for more connection to words we often just mumble our way through.

He recorded it, and forwarded it to a friend who immediately approved. And somehow, something unlocked. “Once one song was out, and someone appreciated it, I believed that more could come to me. I stopped sitting down to try and compose, and instead I tried to channel whatever inspiration came down to me into an actual niggun.” Now he has an entire album’s worth, songs of unity, of teshuvah, of joy (“No you don’t have to be Breslov to be b’simchah, but you gotta be b’simchah to be a Yid”), and of redemption (“When a person has nothing in his life, from a place of ‘ayin’, all the yeshuos will come”).

The song he hopes to write one day, if those floodgates of composition remain open? “Chassidus teaches that there is a lot of power in a wordless niggun,” he says. “Real music goes deeper and reaches higher than words can. That’s a concept I would like to write a song about. I guess I’d explain that idea in the song, and then let the refrain tell its own story by actually being wordless.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 750)