Managing the Central Park Zoh

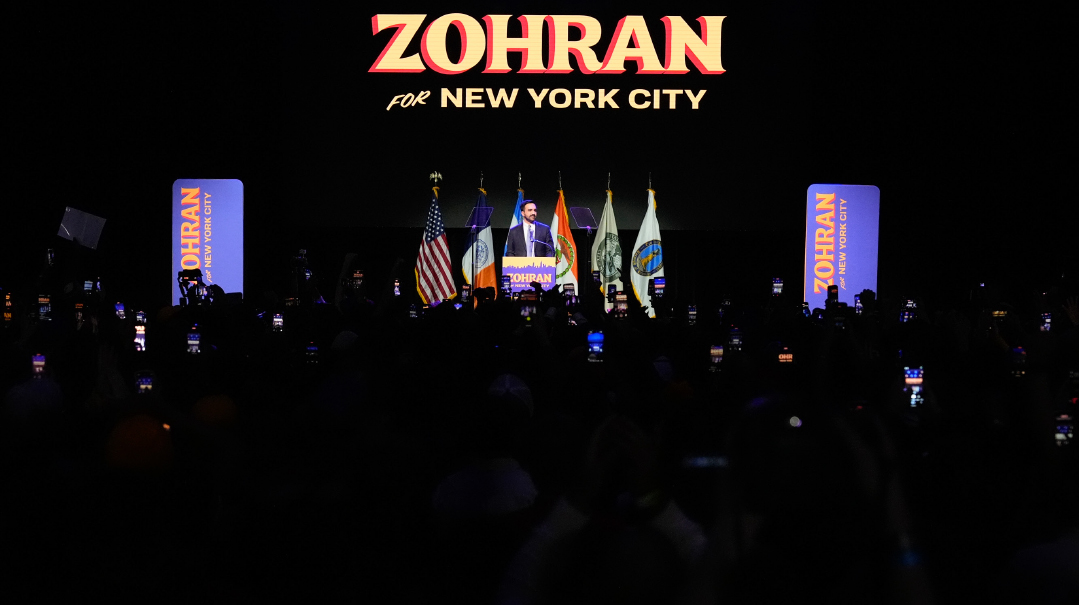

| November 5, 2025NYC’s next mayor is an anti-Israel socialist radical. What next?

For Zohran Mamdani, the race may be over, but the real competition is just beginning.

The newly crowned mayor-elect will oversee a staff of 300,000 people, a school system with 1 million children, a budget of $120 billion, and a GDP of $1.3 trillion. He now has to figure out how to govern a city that can be a zoo of competing interests, demographics, and power brokers; in which friends and enemies flip fast and can be hard to tell apart. The long list of progressive promises that got him in office will now turn into his largest liability, and he’ll hear heckling or hollering from both sides. Supporters want to see action, and enemies have been digging in for months.

Oh, and New York City’s Jewish community finds itself in unknown territory, with an Israel-bashing mayor who wants to arrest Bibi Netanyahu at the helm of the place they call home. In this mess, what will the jockeying positions look like? What is at risk, what are the signs, and is there reason to hope?

Getting to Work

As the mayor gets to work managing the city, askanim are getting to work managing a fraught new relationship with a very different kind of mayor.

“The voters have spoken,” says Rabbi Yeruchim Silber, Agudath Israel’s director of New York governmental affairs. “Our job is shtadlanus, to work with whatever party or candidate is in office in constructive ways, and to be a voice for the community.”

Rabbi Josh Mehlman, chairman of the Flatbush Jewish Community Coalition, puts things in perspective. “Our guides are our gedolim and a few thousand years of experience dealing with all kinds of regimes. Gedolei Yisrael led our efforts and will continue to do so. Like generations past, we work with all types of governments, and we look forward to working with the new administration on behalf of our communities, under the guidance of the rabbanim and roshei yeshivah.”

That’s putting a very brave face on a mayoral race that clearly went against a Jewish community scared of the high-profile anti-Israel positions espoused by the winner. But overall, there are reasons to believe positive askanus can continue.

There’s an initial period in which a cautious dance of admins and activists feel each other out. “New administrations are usually eager to prove that they have everyone’s best interests in mind,” Mehlman says, adding that members of Mamdani’s team have reached out to his organization, expressing interesting in working together for the needs of the community.

Mamdani met several times with representatives of the Satmar community in Williamsburg, and even visited them in their succah on Chol Hamoed. “He told me he’s willing to meet and talk to whomever wants to meet with him,” Rabbi Moshe Indig, leading Satmar askan, told Mishpacha before Yom Tov. “He says he wants to be everyone’s mayor.”

Indig certainly opened a channel to the administration, likely in exchange for his surprising endorsement of Mamdani days before the election — one that drew consternation from the wider community, to say the least.

In his victory speech, Mamdani struck a conciliatory tone, saying, “There are millions of New Yorkers who have strong feelings about what happens overseas. I am one of them… And… you have my word to reach further, to understand the perspectives of those with whom I disagree and to wrestle deeply with those disagreements.” In other remarks, he spoke to his Islamic base, saying that the victory was for “Yemeni Bodega owners, Mexican abuelas, Senegalese taxi drivers, Uzbek nurses, Trinidadian line cooks and Ethiopian aunties.” He also added a thank you in Arabic to Steinway street vendors.

Powers, Policies, and Programs

Beyond the bully pulpit, what can a mayor do, and what are his limits? As an executive, the mayor cannot pass laws, raise taxes, or set most policies. He can veto legislation and control some things by executive order, but his primary powers are in appointing and attempting to control the leadership of city agencies.

The mayor appoints commissioners of over 40 agencies (the City Council has to approve some of them) and court judges. He oversees the operations of more than 200 boards and commissions, and appoints members to various state and federal governmental agencies. Some mayors try to order their appointees around, on pain of firing, but that strategy has limited success.

These appointees can drive impactful changes in city government. For example, a name tossed around for chancellor of schools is former liberal Congressman Jamal Bowman. Mamdani has also indicated he would make changes to the police Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB), giving the board the final authority on police officer discipline — to include firing officers as it deems necessary. This can have a dramatic impact on police confidence in doing their job.

“Because I’ll be the mayor.”

Candidate Zohran Mamdani, explaining to supporters before the election why he thinks he’ll be able to control Police Commissioner Jessica Tisch.

Worst case, it’s key to keep in mind that much of askanus is about working with administration staff, not the mayor. “Much depends on what kind of administration the new mayor puts together,” Rabbi Silber says. “Who will be the police commissioner, chancellor of schools, deputy mayors, and more. There are a limited number of people in New York City who know how to run a city government, and it is more than likely that we already have a working relationship with whomever he will pick.”

Between Jews and Jihadists

Whether or not Mamdani plans to row back on his radicalism once in office, Mamdani has already been warned that his progressive and Islamist bases plan on holding his rookie feet to the fire.

Linda Sarsour, a well-known Muslim activist and pro-BDS supporter of Palestinian terrorists, who lives in Staten Island, engineered much of Mamdani’s rise to power, according to a Fox investigation. Sarsour heads two Muslim and socialist political machines known as MPower and Emgage, big parts of a network of 30 ethnic and religious groups that includes notables like the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) and other Muslim groups. Beginning in 2017, the network raised $24 million and groomed Mamdani as their star.

Sarsour made it clear that she intends to exert maximum pressure on Mamdani, to counter counter-pressure. “Zohran is going to have to tell his own critics that are on the other side… ‘Look out that window, those people outside, these constituents, these activists, these organizers that are outside, I’m accountable to them, because they’re the ones that helped me get there,’” Sarsour said in a message to her supporters obtained by Fox News Digital.

Her remarks also indicated some underlying friction between two sides of Mamdani’s base of support — the woke liberals and religious fundamentalists. “You can’t be a Marxist and a jihadist and an Islamist… all at the same time,” Sarsour said. “You gotta pick a side. Either we’re theocrats or we’re leftists. Like, these things don’t go together.”

So what are the risks of having an adversarial city chief, and what can be done to mitigate them?

Be a Mayor

The first test will be very basic. “He needs to prove that he can govern,” Rabbi Silber says. “A mayor’s job is to collect the garbage and clear the snow. It’s a major test both for Mamdani and the entire DSA. If they can’t do that effectively… even supremely popular mayors like Bloomberg and Lindsay have seen their careers damaged.”

An insider with close eyes on city government, who declined to be named, put it bluntly. “First he has to run the city, to prove he’s a mayor and not just another DSA nut.”

Public Safety

Mamdani has expressed disdain for NYPD and its methods, calling to defund the police in 2020 (he has since backed away from the position). He vowed to disband the key NYPD Criminal Group Database, close Riker’s Island prison, and dissolve the Strategic Response Group, an elite unit that polices terrorism threats, protests, and riots. Mamdani and his pro-Palestine friends have faced off against the SRG at many of their protests. He also wants to create a Department of Community Safety (DCS) that would dispatch social workers or “community relations experts” to some 911 calls, as determined by the call screener.

“Career bureaucrats are going to make this all very difficult. There’s very little he can do without a major rebellion within the police department and city government. Disrupting everyday functions of the police is not something he will want to do,” another askan said.

Mamdani also said he would keep Jessica Tisch, the Jewish police commissioner appointed by Eric Adams who oversaw several years of dramatic drops in crime. Tisch is a strong proponent of the database and SRG.

But Mamdani’s supporters aren’t going to let him off on this one. “I wasn’t really happy about the news,” Sarsour told her audience. “[But] Tisch gotta do what the mayor says. If she doesn’t do that and goes against the mayor, then that’s when we’re going to have to go to Zohran and be like, ‘You definitely made the wrong decision here. What are you going to do to hold your police commissioner accountable to the plan?’”

Anti-Semitism

The biggest and brightest red flag in Mamdani’s rhetoric to date has been overt, covert, and implicit anti-Semitism. These range from the double standard he applies to Israel and the refusal to unequivocally condemn October 7, to his support for calls like “globalize the intifada.”

The most dangerous aspect of this is something that is entirely up to the mayor: Will he use rhetoric that emboldens or encourages violence against Jews, or fail to condemn it? In repeated questioning on the topic before the election, he usually pivoted to talking about “making a city welcoming and safe for everyone.” As mayor, he can also cancel or destroy many initiatives set in place to target and combat rising rates of anti-Semitism in the city. For example, he is likely to try to cancel Mayor Eric Adams’s executive order adopting the IHRA definition of anti-Semitism, because it classifies much of his own anti-Israel slogans as anti-Semitic.

Moshe Davis, Executive Director of the Mayor’s Office to Combat Anti-Semitism in the Adams Administration, is sanguine. “Much of the work we did on anti-Semitism cannot be easily undone,” he says. For example, police training programs, including the next generation of training sergeants, have all been taught about the horrors and history of anti-Semitism, its sources, the current climate, and how it affects the many Jews living in the city. This training is embedded in the NYPD and not going anywhere. Other city agencies have also been trained to recognize and combat anti-Semitism within their ranks or areas of responsibility.

Davis suggests that local communities will object to Mamdani canceling the IHRA definition of anti-Semitism. “The black community will stand with the Jewish community on this,” he says. “We stand alongside them in fighting for their rights, they will stand with us and recognize our right to decide what is or isn’t anti-Semitic.” One may question the reassurance that training, institutional culture, and local alliances can withstand a determined mayor. Mamdani’s base had no problem with his radicalism so far — there’s no guarantee he’ll back off now.

Yeshivos

Of central concern to the Orthodox Jewish community of New York City is the integrity and freedom of our schools. The new mayor moves in liberal circles that include some of the most libelous detractors of the yeshivah system, and there is concern that these individuals will have his ear and move against the mosdos. “Some DSA members have made it their life’s work to shut down yeshivos,” our insider says.

“Among other things, this can affect how the city implements the state guidance on substantial equivalency, the requirement for schools to meet standards of secular education,” Rabbi Silber explained. “Although it is a state rule, it is municipal school districts to certify that schools meet the standard.”

“The Adams administration was a stout bulwark for yeshivos on this,” an askan with close knowledge of the issue said. “They understood our schools and way of life and were determined to protect it. That’s something we will likely never see again.”

The socialist model believes in public, government control of everything, certainly schools. “These people don’t believe in nonpublic schools at all,” the insider says. “They’ll do everything they can to cut school funding, especially the over $1 billion annually that goes to special education in nonpublic schools.”

But there is reason to hope.

Progressives believe in decentralized control of schools. The New York City Department of Education was not under the management of the mayor until the Bloomberg administration, Rabbi Silber explains. It was headed by a board, on which the mayor had a few appointees. The board chose the chancellor of schools, and local committees had additional power. Every mayor since Bloomberg has had direct mayoral control of the department, but it needs to be renewed each year in Albany. Mamdani has indicated a preference for less mayoral control, in favor of giving more power to a 15-member Panel of Educational Policy.

Of course, it is not known what will control the department, but it may be an entity that will be better for our yeshivos and mosdos than the mayor would be. Conversely, less centralized control means there will be no clear address to consult should problems arise.

Business with Israel

The mayor can cancel contracts in place with Israeli companies, and prevent them from doing business with, or even in, the city. Israel’s Technion has a campus on Roosevelt Island in the city, in partnership with Cornell University. Mamdani has already said he is looking at shutting it down, or cutting off city funding.

Much of the work the Adams administration has done on partnerships with Israeli companies cannot be easily undone. “We set up the New York City – Israel Joint Economic Council,” Davis says. This is a group that makes sure Israeli companies can do business here, bringing jobs and tech to New York. “City agencies have firmly entrenched this cooperation, and it will always be in mind. These partnerships are set up and running, and agencies will keep hearing from representatives on this.” While it is possible that Mamdani could violently uproot the entire program, in light of the fact that it is bringing $20 billion of economic output to the city annually, it’s likely he’ll think more than twice before getting rid of it.

Long-Term Damage and the Great Escape

Mamdani’s socialist promises include raising taxes on high earners to pay for gifts to the poor and illegal such as free public busing, freezing rent, and opening city-run grocery stores. Beyond high taxes, these policies can have long-term effects on the city that can damage the Jewish community for decades, well past his tenure. “True socialist policies can destroy sectors of the economy that support our institutions,” an askan says.

For the rest of New Yorkers, there’s the option to flee, but none of the askanim see a serious exodus of the frum community from the city in the future. “We have billions of dollars of infrastructure here,” Mehlman says. “Schools, shuls, mikvaos, organizations… We can’t just pick up and move.

“This is a huge community, where are we going to go?” Rabbi Silber adds. “All to Lakewood? Florida? It’s not practical.”

The Jewish community might not be able to leave, but that doesn’t mean there won’t be a wave of departures. “A few billionaires are likely to leave,” our insider says. “This will suck a lot of tax revenue from the city.”

These numbers are dramatic. If even half of these people make good on their word, the impact on city real estate, tax revenue, and finance would be immense. Taxes will go up on everyone who stays, but it is unlikely the city can cover the shortfall.

The good news is that Mamdani does not have the power to do much of what he has promised. Raising taxes requires approval of both houses of the state legislature and the governor; many analysts see his win as opening the door for a Republican to snare that job. And Kathy Hochul, up for re-election and still smarting from Mamdani’s failure to reciprocate her endorsement, is unlikely to raise taxes sooner.

The mayor cannot control rent in rent-stabilized housing, but he does appoint the members of the Rent Guidelines Board. Those members, though, are restricted by law as to what they can consider in setting rents, and cannot just follow his marching orders.

Free buses are also not under the mayor’s control; fares are set by the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA), whose members are state appointees.

City-run stores would have to be passed by the city council, whose members are beholden to the small businesses in their districts, which would be crushed by such stores — if they work.

It’s still early, and there is so much that still has to take shape. But overall, the message of our leading askanim is that we have been here before, we’ve done this in the past, and Hashem always helps.

Take heart, NYC.

Oops! We could not locate your form.